Column: Care to learn Spanish? Dodger broadcast legend Jaime Jarrin teaches almost nightly, and the course is free

One day in the locker room I overheard an Asian gent tell someone he learned English by listening to the radio as a kid. Namely, he tuned in to the late Chick Hearn calling Laker games and Vin Scully calling Dodger games.

“Where I grew up, I could only get certain stations,” he said, and the signals were strong and clear for both sports teams. So he turned up the volume and went to school, with a pair of legendary broadcasters as his English teachers.

I loved the image of it. A kid with his ear to the radio in a city that is a world without borders, where more than 200 languages are spoken, and where cultures bump and blend.

And I got to thinking.

Like a lot of Southern Californians, I don’t have the option of watching the Dodgers on TV, thanks to the obnoxious and enduring greed-driven battle over broadcasting fees. And I can no longer listen to Vin Scully on the radio, because he packed his golden mike into a velvet box and said goodbye.

So I began punching in 1020 on the AM dial to hear broadcasts of Dodger games in Spanish.

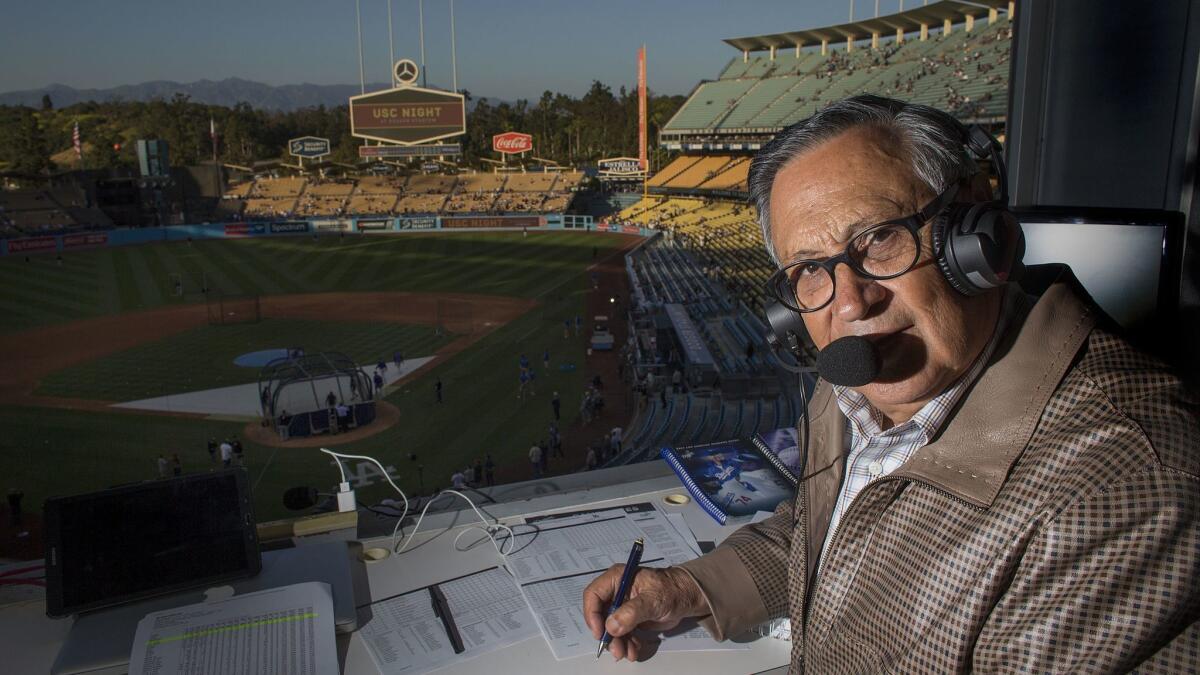

The season is young, the nights are warming now, and I confess that I can’t always show up for class. But when I do, the other Dodger broadcast legend — Hall of Famer Jaime Jarrin, in his 59th year with the team at the age of 81 — is my Spanish teacher.

Jarrin was born and raised in Ecuador. He has a warm, calming voice. It’s rum and butterscotch and black coffee, and he speaks slowly, clearly, poetically.

Lanzamiento viene (here comes the pitch, or the pitch is coming) are two simple words. But Jarrin’s delivery turns them into a little song about the expectation that rides on every pitch.

Curva muy abierto, una bola dos estraic. (Curve ball way outside, one ball and two strikes.)

And then there’s his home run call.

Se va, se va, se va, despidala con un beso. (It’s going, going, going, kiss it goodbye.)

I didn’t go into this entirely cold. I speak, read and write a little Spanish, but have long been frustrated that I haven’t taken it to the next level, where I can comfortably talk to people and pull off an interview.

Another motive for my desire to finally get closer to fluency is that we’ve been dragged through an ugly, polarizing time politically, with racial and cultural differences exploited and scapegoats targeted.

To that I say, despidala con un beso.

My dad’s grandparents, who landed in California from Spain almost a hundred years ago and opened a little grocery store, spoke only Spanish, but they died before I was born. My father spoke Spanish as a kid, but not when I was growing up, so I had no idea if he knew more than a few words.

I’ll never forget a trip to Spain with my father and brother, thinking I was going to be our translator because I took Spanish in junior high and high school. We got lost, and I asked a stranger for directions, but couldn’t understand a word of his response.

My dad, to my amazement, jumped in and bailed me out. His Spanish was as polished as a gem hidden away in a box for years, and he used it flawlessly. I envied him and regretted that he hadn’t raised me to be bilingual, but that’s the way it was. My mother had grown up speaking Italian, but put it away as an adult. Some families, targeted as immigrants, wanted to blend in as possible, and even now, language in California is a story with many narratives.

I had a Chinese student at Cal State L.A. who wrote beautifully about her desire to hold on to her first language, as well as her disappointment that her little brother resisted. She had a classmate, meanwhile, who wanted so badly to be seen as a native Angeleno, she disguised the fact that she spoke perfect Chinese.

Jaime Jarrin was college-educated in Ecuador and took eight years of English there but felt lost when he got to Los Angeles, so he enrolled in a class downtown and began a career that’s in extra innings, with no end in sight. I’d never met the man, but on Wednesday I gave him a call to deliver the news that he’s my maestro de Español, or one of them, anyway.

“Lots of Anglos have told me over the years that they improved their Spanish through my broadcasts,” said Jarrin, who recalls a flurry of new fans when Dodger pitching phenom Fernando Valenzuela conquered L.A. in the 1980s.

Dialects differ a bit when it comes to Spanish from Mexico, Central America, South America and elsewhere, so I asked Jarrin how he handles that.

“What I do is use the proper language, the proper words,” he said.

I told him I had been listening to a Spanish radio show earlier that day about how to succeed in business, and one host said it was important to learn English. Good advice, for sure, but if everyone followed it, we wouldn’t need Spanish radio or television, and something would be lost.

“I’ve always believed that if you come to this country, you have to learn this language. We are in the United States,” said Jarrin. “But at the same time I am a champion of bilingualism, and I think for people who speak two or three languages, everything is open to them.”

Jarrin told me to come by the game Wednesday night to say hello.

It was a little intimidating, because we spoke in Spanish much of the time, but my teacher was willing to work with me.

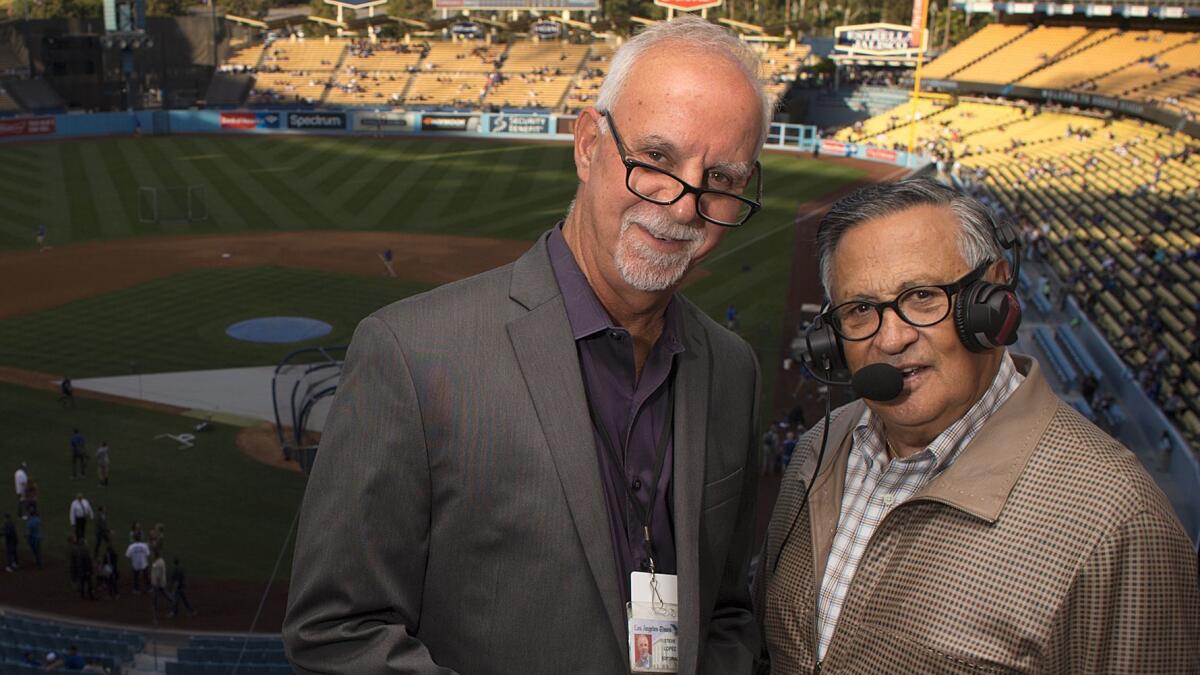

I met Jarrin’s broadcast partner, his son Jorge, and also his grandson Stefan, 26, who used to play in the Dodger rookie league and is now a scout.

Here’s a surprise: Stefan, who understands Spanish, said he doesn’t speak it very well, primarily because his parents spoke English around him when he was a boy. And his grandfather’s Spanish is so smooth, Stefan is too intimidated to try matching it.

The engineer, meanwhile, Efren Meza, told me his own Spanish has been elevated. Five years in a booth with Jaime Jarrin can have that effect.

Soon, Clayton Kershaw had taken el monticulo to face the poderoso (powerful) Colorado Rockies.

He looked in for a sign and went into his windup, and up in the booth, so did Jarrin.

Lanzamiento viene….

Get more of Steve Lopez’s work and follow him on Twitter @LATstevelopez

ALSO

Getting older, and falling apart, but no shortage of role models for fighting on

California’s environmental crusaders helped save our state. Now, they face down Trump

Strangers weave a safety net for woman who lost it all, including her home

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.