Marijuana production faces ‘war’ from Asian American communities in San Gabriel Valley

- Share via

The men and women collecting petition signatures outside Metro Super Market in Temple City warned of a marijuana takeover and greedy politicians eager to speed it along. They accused Andre Quintero, the mayor of El Monte, of wanting to make the San Gabriel Valley famous as a cannabis hub.

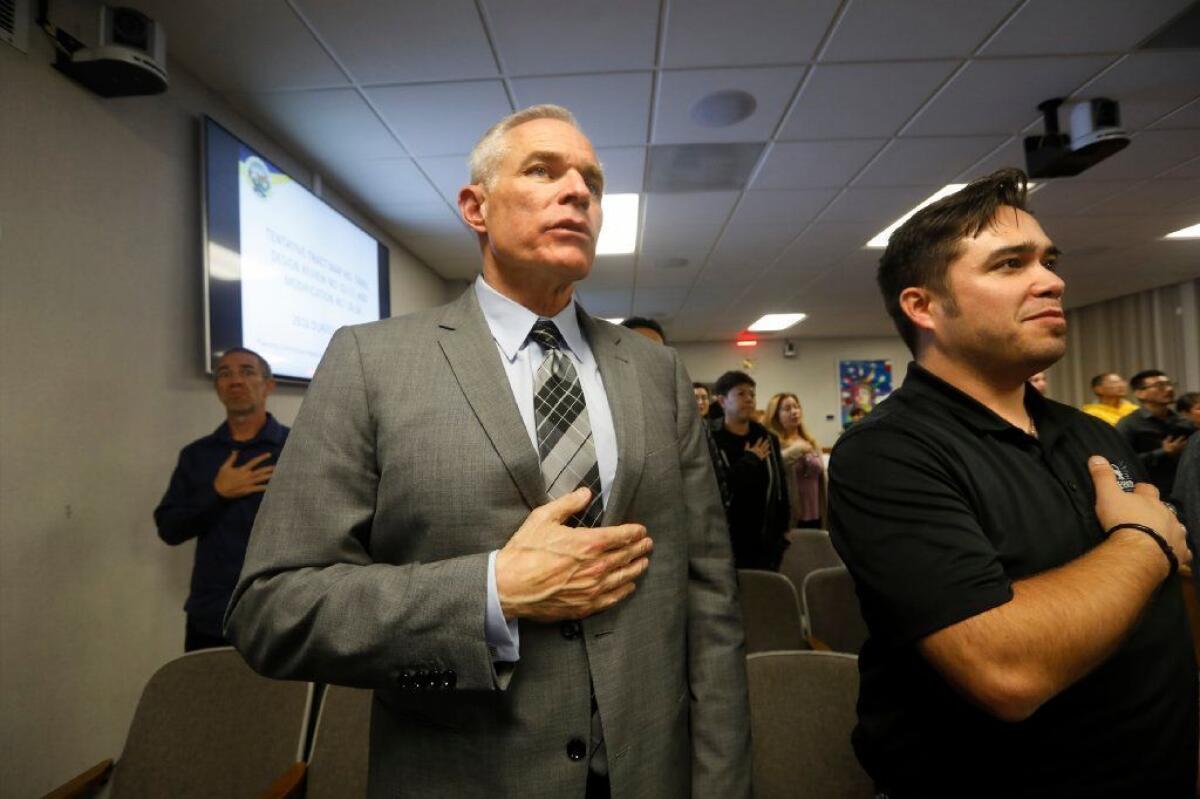

Quintero has backed a sprawling marijuana facility in El Monte as the start of a larger effort to make cannabis an economic engine for a working-class, predominantly Latino city that has long suffered from financial woes. He also sees marijuana cultivation as a way of boosting the city’s standing.

“I’ll look at the package and it will say ‘Made in El Monte,’ and I’ll smile,” he said.

But the city’s push into marijuana is facing an extreme backlash from its more well-heeled neighbors in the San Gabriel Valley, who fear cultivation will bring crime and blight.

“You will hear helicopters overhead, people shooting in the street, maybe prostitutes walking around,” said Daniel Ding of Temple City. “It will destroy the city.”

“It’s a war,” said Fenglan Liu, a Temple City resident who lives near the proposed site. “It’s a marijuana war.”

The dispute has sparked loud protests, talk of a political recall and a lawsuit, and laid bare clashing views of what large-scale cannabis production bodes for cities, their residents — and their neighbors. It’s part of a larger debate going on in communities in California and other states that have legalized marijuana, where some struggling cities are trying to lure pot businesses to help increase jobs and boost sagging tax revenue.

The conflict also has underscored the economic imbalance between El Monte, a perennially strapped city where the median household income is $43,500, and nearby cities like Arcadia and Temple City, where many households make twice that. El Monte must look to industries outside “the mainstream” to bring investment and jobs, Quintero said, industries his city’s wealthier neighbors can afford to snub.

Temple City and Rosemead are suing El Monte, alleging that it minimized or simply ignored many of the project’s environmental risks. City attorneys also say El Monte understated the strain on the region’s public safety resources and water supply.

In December, the El Monte City Council approved the 71,658-square-foot facility to grow, process and distribute medical-grade marijuana.

Both sides have since dug in.

Opponents, many of them Asian Americans, are trying to force a referendum and, if that fails, a recall of El Monte officeholders, whom they call corrupt and deaf to constituents. Quintero claims “the Chinese group was weaponized” by political enemies.

The developer of the cultivation center, Teresa Tsai, lives in Temple City and said she was raised in a “traditional, conservative Asian family.”

Tsai, 39, said the San Gabriel Valley is already awash in illicit marijuana businesses that — unlike her development — are not regulated and pay no taxes.

“Cannabis is all around us,” she said, noting the state allows marijuana to be delivered even to cities that ban its sale. “There’s illegal shops all around, advertised on Yelp, Weedmaps, operating without a license. It’s the illegal shops that are selling to children, selling untested products. Isn’t it better to have a facility that’s regulated than letting illegal ones pop up?”

Tsai estimated it would take between six months and a year for her operation to open, depending on how quickly the city and state inspect it. She must pay El Monte $828,700 in fees the first year, $955,420 in the second and $1.15 million in the third, according to city estimates. An annual fee of $175,000 would go to a “community benefits fund,” which Quintero said could finance after-school programs, youth education about illegal drugs and alcohol, and cracking down on illicit marijuana rackets.

A cascade of marijuana development in El Monte could follow. A city planning commission on Tuesday approved a second facility, abutting the first one and twice its size. It will now go before the city council for approval.

Some of the criticism has come from within El Monte — from both Latino and Asian residents.

“They sold their soul to the devil,” said Alan Zhong, an El Monte resident. “I feel they threw their morals on the garbage.”

Critics have challenged the El Monte council’s blessing of the first project, citing campaign donations from the developer and her associates to three of the city’s five council members, including Quintero.

It’s a conflict of interest, real straight. It is definitely, obviously, a conflict of interest.

— Zig Jiang, Hacienda Heights resident and opponent of the marijuana development

Quintero said Tsai’s contributions had no bearing on his vote, and that he has been maligned by political opponents who have characterized campaign donations as bribes.

“It’s common for people to support officeholders who support their ideas,” he said. “They’re not going to support people who are against cannabis.”

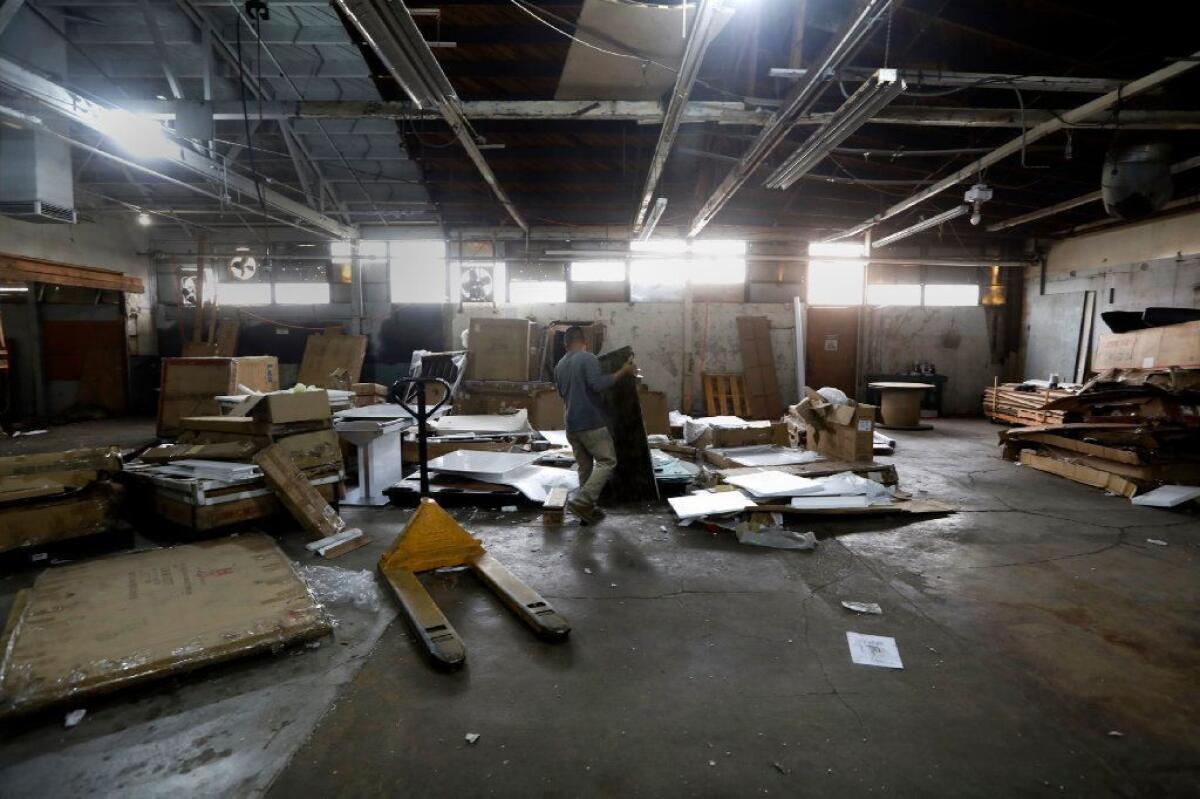

The facility — currently a furniture warehouse — is on Temple City Boulevard, which divides El Monte and Temple City. Though the marijuana operation would be on the El Monte side of the street in an area zoned for manufacturing, across the street are Temple City homes and apartments.

Ellis Raskin, an attorney retained by the project’s critics, said El Monte has tried to play down the development’s environmental risks by reviewing the projects one at a time, rather than gauging their collective impact — a tactic known as “piecemealing.”

After weeks of soliciting outside supermarkets and restaurants, the project’s opponents on Wednesday delivered to El Monte’s city clerk what they said were the signatures of more than 5,700 city voters opposed to the development — enough to trigger a referendum.

An El Monte spokeswoman said the city would review the signatures before sending them on to the Los Angeles County Registrar-Recorder, which would verify their legitimacy. If the signatures are valid, and the petition was indeed signed by 10% or more of El Monte voters, the city council could either repeal its agreement with the developer or put it to a popular vote.

Opponents of the development say home values will drop and crime will climb, that children will grow inured to marijuana, and nearby schools — there are four within a one-mile radius of the site — will be threatened.

Some experts say it’s no surprise that opposition to marijuana businesses is coming from Chinese Americans.

Robin Wang, a philosophy professor and director of Asian American studies at Loyola Marymount University, said the Chinese word for marijuana — dama, translated literally as “large anesthesia” — connotes a poisonous stupor. Marijuana is criminalized in China and is generally believed there to have no medicinal value, Wang said.

To explain why he opposed the El Monte development, Cliff Chih said a relative, now about 30, began smoking marijuana at 15.

“He’s kind of useless now — he can’t support himself,” he said. Chih, a Temple City resident, said he does not believe marijuana has medicinal use.

For his part, Quintero said he is girding for the next recession.

El Monte recorded an $8.4-million deficit in the last fiscal year, according to its annual report. Quintero said El Monte has tapped reserves to pay its bills — a practice he called “not sustainable” — and can ill afford to turn away investment in the city.

“We have very little margin for error,” he said. “And I don’t want to keep going back to the well and asking voters for a higher property tax.”

Assemblyman Reggie Jones-Sawyer, who has championed marijuana development in his South Los Angeles district, agreed that cannabis can be a key revenue source for small cities. Maywood aggressively courted marijuana development in 2017, and Adelanto’s then-mayor spoke of turning his high desert city into the “Silicon Valley of medical marijuana” before his home, office and a local marijuana dispensary were raided by FBI agents in 2018. No charges have been filed against the mayor, Rich Kerr, who lost reelection in November.

But how marijuana operations could affect home values is an open question.

Cheng Cheng, an assistant professor of economics at the University of Mississippi, studied Colorado home prices after marijuana was legalized there in 2012 and found they went up about 6% when a dispensary opened nearby. But how a large cultivation center affects property values, Cheng said, hinges on how the local market views marijuana.

Quintero said land in El Monte’s manufacturing zones has become more valuable as the cannabis industry eyes it.

From the outside, he said, the warehouse that will contain 12,555 feet of canopy space — about 8,850 plants at a time — would be indistinguishable from any other business.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.