#FergusonSyllabus: How do we teach teens about injustice?

For America’s students, this last year has been a living history lesson in the making.

It's common for the average teenager to wake up to a social media stream of dash-cam videos, hashtags and articles depicting police shootings and unrest in Ferguson, Mo., Baltimore, or even right here in Los Angeles.

Despite this full-on immersion, some teachers may find it difficult to broach this topic in the classroom. Sure, many of us who didn’t live through the civil rights movement of the 1960s learned about that era in school. But how do you teach about a movement that is still in progress?

Last year, the #FergusonSyllabus hashtag became a way for educators on Twitter to share books, blog posts and articles to help college students understand what was happening in Ferguson. As the school year starts again, the need for accessible materials has resurfaced.

Below, three educators – two college professors and a member of the team who worked on a documentary about white people – weigh in with their selections for building a timely syllabus on race and injustice.

We’d like to hear from you as well. What books, articles or videos would you suggest for the classroom, and why? And what age do you think that material would be useful for? Use the hashtag #FergusonSyllabus on Twitter, or let us know in the comments.

And, don't miss our next article in this series on education after Ferguson. We'll talk about teaching about Ferguson to younger children.

Rethinking two black leaders

Ainsworth Clarke, assistant professor of African American Studies and English at the University of Illinois at Chicago:

Kwame Ture, left (AP file photo, 1966). Martin Luther King Jr, right. (AP file photo, 1967).

“My first text would be Kwame Ture and Charles Hamilton’s 'Black Power: The Politics of Liberation.'

'Black Power' is important because it talks about what is happening in the 1960s, and in the civil rights movement, within the context of other struggles for justice internationally. It forces you, as a reader, to look at yourself in a way that we’re not used to doing. I think there’s something to be gained from looking beyond our own borders, and thinking about how others live and think elsewhere. (You can also listen to a speech by Kwame Ture here.)

I teach that text in combination with Martin Luther King’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail.

I think most people are used to a myth of Martin Luther King Jr., where they conflate his nonviolence with being passive. But if you read this piece, you can hear King’s anger. It registers on the page. He talks about his children. You can see him struggle to answer his 5-year-old son when he asks, “Daddy, why do white people treat colored people so mean?” And that rawness, that immediacy, encourages students to think out loud and express their thoughts.

Overall, I try to avoid turning the question of race and identity into an abstract, academic question. I think both of these pieces, especially together, show that active citizenship requires engagement. It takes courage. I’ve taught this to first-years in college, but I think that this could work for high school seniors also."

Christianity, and thinking beyond black and white

KC Choi, Associate Professor in the Department of Religion at Seton Hall University:

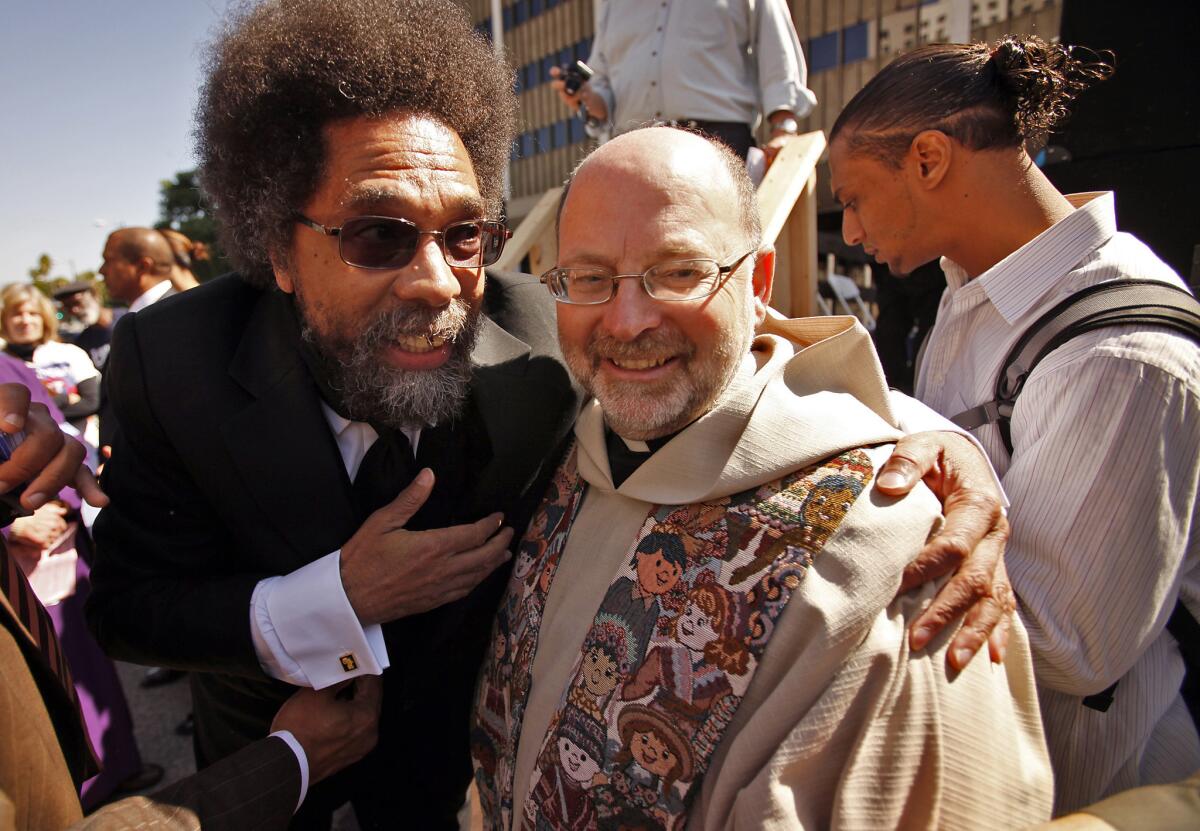

Seib, Al –– B581604708Z.1 LOS ANGELES, CA OCTOBER 07, 2011 –– Professor Cornel West, left, hugs Father Chris Ponnet, Director/Pastor of the St. Camillus Catholic Center for Pastoral Care, right, after speaking at a Interfaith Communities United for Justice and Peace rally that blocked Los Angeles Street Friday morning. The ICUJP marked the 10th anniversary of the US war in Afghanistan with the protest that started at La Placita Church and a march past city hall ending with a rally at the downtown Federal Building where 15 protestors were arrested by the LAPD.(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times)

Professor Cornel West, left, hugs Father Chris Ponnet, director and pastor of the St. Camillus Catholic Center for Pastoral Care, after speaking at an Interfaith Communities United for Justice and Peace rally in 2011. (Al Seib/ Los Angeles Times)

"The first book that I would recommend is James H. Cone’s 'A Black Theology of Liberation.'

I teach theological ethics, and this text gives us a powerful point of departure for thinking about race. Cone begins by proposing that mainstream Christian theology has assumed a white God, but if you want to be truthful, God should be understood as black. Blackness, unlike any other racial category, is a symbol of oppression in the modern world. Cone writes: 'Either God is identified with the oppressed [...], or God is a God of racism.' Once you get over the initial shock of that claim, his book becomes a provocative guide to thinking about how our lives, at the personal and structural levels, fall into the same pattern that mainstream Christian theology has fallen into. Whiteness is the norm that defines our existence. It’s an exciting, eye-opening read for college students. It’s startling. But I think we need to be shaken out of our daily routines to think seriously and truthfully about racism.

I also find this conversation between Cornel West and Jorge Klor de Alva very helpful. If we’re serious about putting together a syllabus that will address racial injustice, we have to include voices beyond black and white. But, where do you start? That’s the hard part since much of our discussions on race are still very much stuck in the black/white binary.

That's why this interview is so interesting, a terrific exchange between an African American scholar and a Chicano scholar. Though it took place almost 20 years ago, the questions they address are still front and center in our current discussions on race. Very early in the conversation, Klor de Alva proposes that West is not a “black man” as a way of expressing his skepticism over the benefits of racial categories of identity. (Later, Klor de Alva suggests that West is more "Anglo" than black.) Pointing to the incoherence of racially categorizing Latinos/as, Klor de Alva argues that racial identifications do more harm than good, and focusing on class rather than race advances civil rights in a more inclusive and effective manner. From the very start, this is another provocative read, and it really pushes you to reflect about the benefits and hindrances of racial identity, but not only from a black/white perspective."

What about white people?

Lara Drasin, former director of media and partnerships for Define American:

"Stories foster empathy, which make them especially good discussion pieces to use in classrooms. But the students have to be engaged. That’s something we kept in mind at Define American, when we made a documentary with MTV as part of their Look Different campaign. It’s called 'White People.'

(Editor's note: The documentary was directed by Jose Antonio Vargas, who is a partner with the Los Angeles Times in launching the new digital magazine #EmergingUS this fall. The documentary can be watched in its entirety above.)

The documentary explores the concept of "white privilege," which is incredibly complex, sensitive and often misunderstood. White People' makes it more accessible by introducing the subject through real-life situations and young people, in their own words, as they grapple with it the way we might at home.

The conversations we see on screen are facilitated between people who normally might not talk about race with one another, and they can serve as a model for viewers of how to talk about these issues from a place of open-mindedness and empathy.

For example: There is so much unconscious, unintended bias embedded in the language we use. In 'White People,' one character explains that casual use of the word "ghetto" upsets her, because she feels like it is often used to describe who people are or their racial identity, as opposed to where they live. Many of us may not be aware that the words we use can imply certain beliefs and perceptions – and sometimes hurt – until we are able to have honest and constructive conversations about difficult issues with one another.

Viewers can continue the conversation after the film by downloading the discussion guide, which was made in collaboration with the ADL (Anti-Defamation League). The guide can be used by teachers, student groups, book clubs, families, friends – anyone who wants to dive deeper into the subject responsibly and respectfully. Teachers are often nervous about talking about race or bias in the classroom because they don't want to offend anyone or don't feel confident enough in their ability to steer such a delicate conversation. The guide provides them with the framework and vocabulary to more comfortably pose these provocative questions and keep the class discussion on track.

It's important for teachers to know that it’s not their responsibility to provide answers. No one has the answers. But teachers have the power to facilitate open conversation in a safe space where everyone feels respected and heard, and that can help raise a more empathetic, aware and interconnected next generation."

Follow me @dexdigi for more on the intersection of culture and the Internet.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.