L.A.’s school board president wants every district graduate to be eligible for a four-year public university by 2023

Former Los Angeles schools Supt. Michelle King made “100% graduation” her central goal for the nation’s second-largest school district. Now the L.A. school board president wants to up the ante — and, by 2023, have every student graduate meeting requirements to enroll in one of the state’s public four-year universities.

The board is scheduled to vote on LAUSD Board President Monica Garcia’s resolution, Realizing the Promise for All: Close the Gap by 2023, on Tuesday. The district estimates that 56% of 2017 graduates met those requirements, according to a district spokeswoman. The district currently allows students to graduate with D grades in the required classes instead of the minimum C grades that Cal State and the University of California require.

So how would this giant leap forward happen? The resolution sets giant goals — mostly concerning academics. By 2023, it mandates, among other things, that:

- All students identified as English learners in kindergarten or first grade be reclassified as fluent English proficient by the end of sixth grade;

- All third-graders meet or exceed standards on California state standardized tests;

- All eighth-graders head to high school with a C or better in English and math;

- All high school students take at least one college-level class.

Some of the goals are similar to those in King’s strategic plan, though that plan foresaw more gradual progress.

The resolution calls for schools to develop spending plans that would allow even the lowest-performing students to achieve rigorous academic standards. Supt. Austin Beutner would have to report in 120 days on “the steps being taken to support high and highest need schools in hiring and retaining highly qualified teachers.”

The proposal does not suggest how much reaching the goals would cost or include annual benchmarks or how officials would respond if goals aren’t reached.

Garcia did not reply to requests to talk about the details. Among the questions are how such fast improvement could be made without cutting corners to give students grades and credit they might not have earned. The district already has received criticism for using a wide range of “credit recovery” courses to help boost graduation rates.

“I believe this resolution is intended to create a sense of urgency about closing achievement and opportunity gaps and that’s important,” said Ryan Smith, the executive director of the nonprofit advocacy group Education Trust-West. “We need concrete steps to ensure that schools and districts are changing practice and getting the results necessary to close those gaps.”

Board member Nick Melvoin said the district would need measures in place to make sure standards are rigorous.

“We could have 100% graduation tomorrow if you say, ‘Show up to school and graduate,’” Melvoin said.

Board member Kelly Gonez said she wants to see changes to the resolution before she would vote for it, including information on costs. She said she would prefer more of a focus on closing the gaps between lower-performing and higher-performing groups of students.

“I think back to the No Child Left Behind experience where you had a similar sort of 100% goal for all schools and then requisite supports were not given,” Gonez said, referring to a past federal law that said all students would have to be academically proficient by 2014.

One way to help meet these proposed ambitious goals would be to redirect some funding from lower-needs schools to those with the highest-need populations, said Sara Mooney, an education program officer for United Way of Greater Los Angeles, which helped draft the resolution.

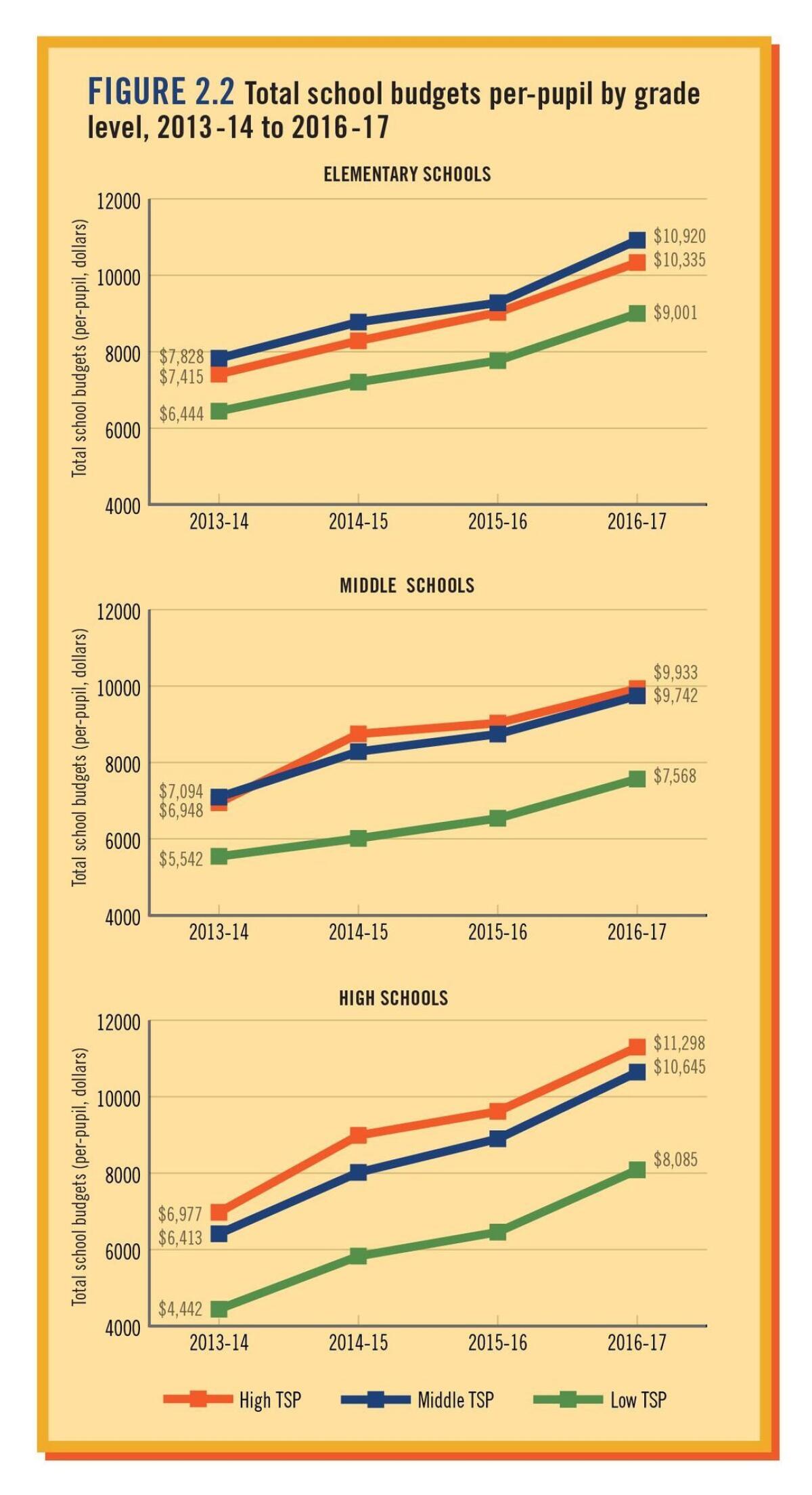

United Way also released a report Tuesday in partnership with other advocacy groups, asserting that needy L.A. students are not benefiting as intended from extra funds set aside to help them under the state’s Local Control Funding Formula. These LCFF funds are supposed to provide intensive services to low-income students, English learners and foster youths. But too much of the money is being diverted to other purposes, the report claimed.

School districts get additional dollars for every low-income, English learner and foster student enrolled. In L.A. Unified that adds up to about $1.1 billion to the district annually. The district last year settled a lawsuit after it was accused of misusing some of that money for special education students.

“The district continues to siphon off money” in the same ways, said UC Berkeley education professor Bruce Fuller, who directed the report.

According to the report, elementary schools with the highest share of the targeted students (more than 90%) receive about $600 less per student than elementary schools with 60-90% of targeted students.

The school board recently approved a Student Equity Needs Index, which takes into account problems such as gun violence and asthma in a school’s neighborhood to try to reallocate some funds to high-need schools. That is one way the district could help reach the right targets, said Pedro Salcido, the district’s director of finance policy.

“To deliver on the promise of the LCFF, the District must be more transparent. The District must make sure that it is investing in proven strategies and programs to improve student achievement,” L.A. Unified Supt. Austin Beutner said in a statement about the United Way report. “The District must also be more accountable to ensure it achieves the goals of the LCFF.”

Reach Sonali Kohli at Sonali.Kohli@latimes.com or on Twitter @Sonali_Kohli.

UPDATES:

11:25 a.m.: This article and accompanying photo caption were updated to reflect that 56% of recent graduates met college entry requirements, not 31.9% as stated in the Close the Gap resolution.

This story was originally published at 5 a.m.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.