In California, a cellphone call to 911 can be hit or miss

STOCKTON -- — “My mom needs help!”

Susana Tupou was frantic as she raced across the street toward a neighbor mowing his lawn. Moments before, the 16-year-old had discovered her mother face-down on the living room carpet.

The neighbor, Antonio Zamora grabbed his cellphone -- the only phone he had -- from his belt clip and punched in 911.

The global positioning system linked to Zamora’s phone should have sent information to California Highway Patrol dispatchers, showing his location in a subdivision of two-story homes in the northeast part of the city.

But on this day last fall, the CHP’s screen came up blank.

As the minutes ticked by -- with Susana wailing in the background, “What can we do? . . . What can we do?” -- Zamora struggled to make one operator, then another, understand just where the emergency was.

The ordeal bared critical vulnerabilities in California’s 911 system. Had Zamora used a land line phone, his address would have popped up automatically on dispatchers’ computers. Instead, by using a wireless phone, he was depending on less reliable tracking technology.

Despite technological advances and reform efforts over the last decade, the automated system often fails to determine the location of cellphone callers. A Times review of data for August and September, the only months for which numbers are available, found that more than 1 in 5 911 wireless calls in California -- more than 300,000 in all -- came into CHP dispatch centers with no location information.

Hundreds of thousands of additional calls arrived with limited or imprecise information.

Under federal regulations, dispatch centers in California that accept wireless calls are supposed to receive, at a minimum, the address of the antenna transmitting the call -- a rough indication of the caller’s location, officials said. In areas like Susana’s neighborhood, served by call centers with advanced technology, a dispatcher should be able in nearly all cases to plot locations within a maximum of 980 feet.

“This is critically important to public safety and critically important to people -- to be able to pick up the phone and have the local police or local fire department find you,” said Kevin J. Martin, chairman of the Federal Communications Commission.

The FCC released an order Tuesday to tighten cellphone tracking standards for 911 calls over the next five years, highlighting national concerns over finding wireless users in emergencies.

Many times, technical glitches don’t matter. A caller knows where he is and can convey the location in short order.

In the case of Susana’s mother, Katinia Finau, it mattered a great deal.

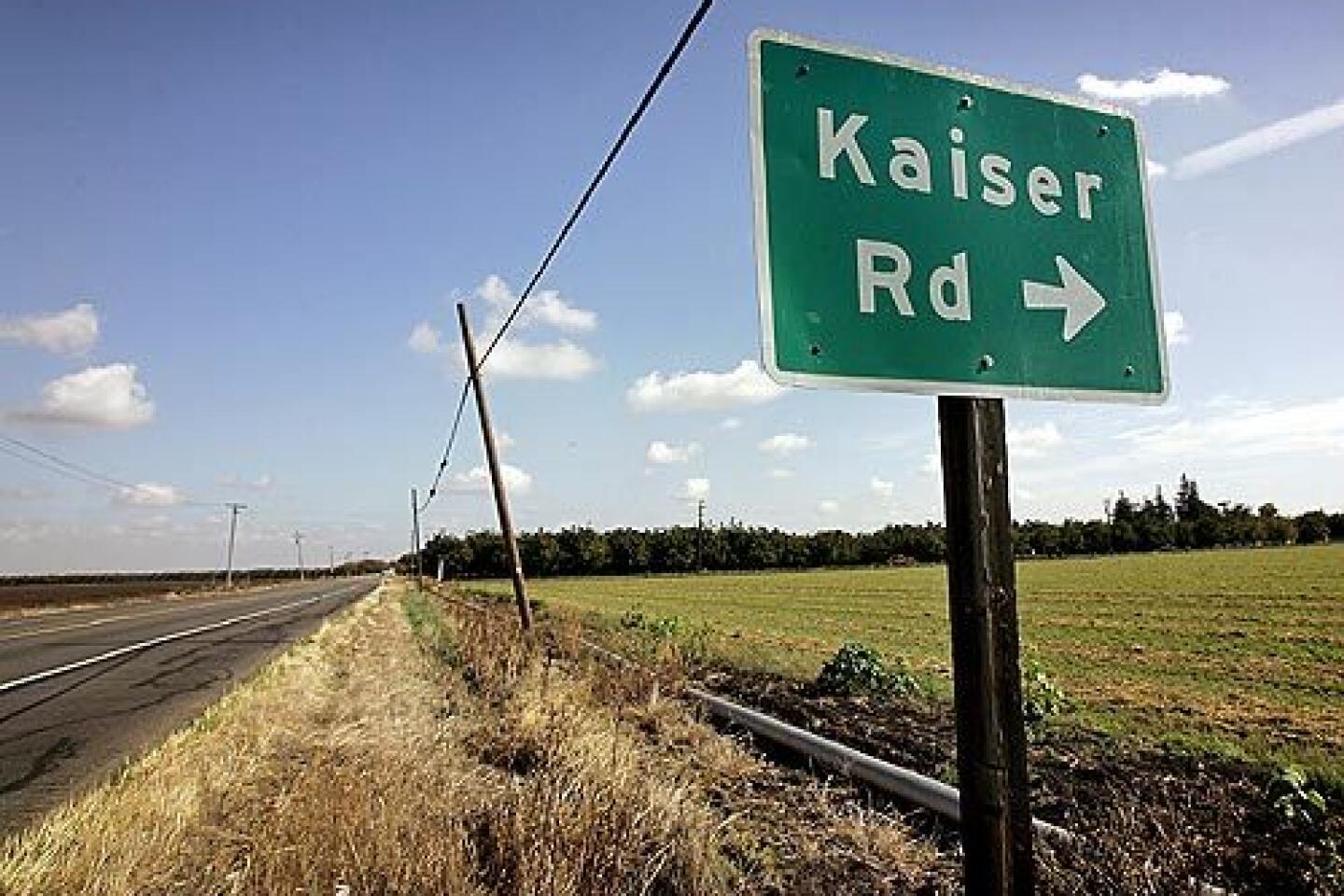

Without the aid of electronic tracking data, the risk for human error multiplied. When the CHP dispatcher transferred Zamora’s call, as is customary, to a local emergency operator, she also passed along a misunderstanding. She referred to Susana’s street, Keyser Drive (pronounced Key-zer) as Kaiser. Perhaps complicating matters, Zamora repeated the incorrect pronunciation.

The new dispatcher sent rescuers to Kaiser Road, in a farming area 13 miles from where Susana was waiting.

‘I’m scared’

Ten minutes after Zamora placed his call, he was standing with Susana, looking down at Finau’s body.

At the dispatcher’s request, Zamora asked Susana to start CPR and press on her mother’s chest.

“Oh, no, I’m scared,” she said.

“But that’s your mom,” Zamora told her.

“I can’t do it!” the girl cried.

Even the dispatcher seemed to be growing concerned. She asked Zamora if the firetruck was coming.

“We don’t hear the siren,” he said.

More than 15 minutes into the call, Susana grew impatient. The girl, who is hearing-impaired, ran up and down the street, knocking on neighbors’ doors for help.

Desperate to make the dispatcher understand where they were, Zamora gave the dispatcher major cross streets and landmarks such as an auto mall and two nearby schools. He spelled the street name for her as well.

Still uncertain, the dispatcher told Zamora to find Susana. “Let me talk to her,” the dispatcher said.

Zamora raced to the corner to get the girl. Susana returned with Zamora’s cellphone and told the dispatcher her address on Keyser Drive.

“I need your house phone number” the dispatcher said.

“My phone is off,” the girl responded.

“You don’t have a phone number?”

“No,” Susana said.

It had been disconnected because the family chose to use cellphones only to avoid the additional cost of a land line. Zamora didn’t have a land line either. The home where he was mowing the lawn was an unoccupied house he was preparing to sell.

After an additional barrage of questions about her address, Susana became overwhelmed.

“I don’t know. . . . I’m sorry,” the girl said.

Limited technology

The glitches and gaps in wireless location technology have become more significant as the proportion of 911 calls made with cellphones has soared.

In many areas, including California, wireless phones are used for a majority of emergency calls. About 1 in 7 households in the United States don’t even have a land-line phone, relying solely on cellphones.

Generally speaking, most cellphones sold in the last three years are equipped with one of two types of tracking technology. Each has limitations.

Verizon, Sprint Nextel and MetroPCS use GPS technology, relying on satellites to get a geographic fix on a caller. The system tends to work best in rural areas, but can lose track of callers inside buildings or the urban canyons created by high-rises.

AT&T and T-Mobile rely on cellphone transmission sites to triangulate on callers -- locating them via radio signals from at least three towers. This works better in urban areas, but is less effective in rural regions where transmission towers are fewer and farther apart.

The FCC requires that 95% of a cellphone carrier’s calls be automatically tracked to within 980 feet of a phone’s location. But until now, the commission has permitted wireless companies to average their performance across huge, multi-state service areas.

Swayed in part by a recent study showing wide variations in the accuracy of tracking from city to city, Martin of the FCC recently pushed through a plan to tighten standards. Within five years, carriers must ensure that they are meeting the accuracy standard at nearly every individual dispatch center nationwide.

“People in every local community need to have the same kind of 911 service, whether you live in San Diego, Los Angeles or San Francisco,” Martin said.

Several major wireless carriers say that the plan’s cost will be staggering. The industry has already spent billions of dollars improving call tracking technology to meet the requirements thus far, according to the International Assn. for the Wireless Telecommunications Industry. In addition, industry advocates say, some areas present insurmountable geographic or environmental challenges.

Dispatchers say missing location information can cost lives.

Last year, a 49-year-old motorcyclist called 911 twice on his cellphone as he lay critically injured in a dark Illinois cornfield. He was unable to say where he was, and rescuers took four hours to find him because they lacked the latest tracking technology. By then, he had died.

In April, Ohio police searched desperately for the 84-year-old victim of a kidnapping and rape who called three times on her cellphone. At the end of her fourth call, she said, “I don’t know where I’m at.” Authorities couldn’t track the calls and the woman was found dead the next day.

When location information is absent, “basically, you’re going into that call blind and hoping you extract all that information from the caller and not get disconnected,” said Daphne Rhoe, head of the state’s wireless 911 programs.

California authorities are investigating possible causes of the breakdowns. All of the problem calls are pouring into the CHP, whose centers are designated as the default destination for calls that lack location data.

As it is, CHP dispatchers are struggling to handle nearly three-fourths of the state’s estimated 8 million to 10 million wireless 911 calls each year. Callers to some of the agency’s busiest centers, in Los Angeles and San Francisco, already experience lengthy delays or dropped calls.

Sometimes the problem is incomplete information, forcing dispatchers to refresh their computer screens to get more precise coordinates. The process can take 15 seconds or more.

“How much can a car burn in 15 seconds?” asked Linda McNeill, who until recently was the CHP’s 911 system coordinator. “How much can you bleed out in 15 seconds?”

Exasperation

Twenty minutes after calling 911, Zamora left the room to wait in the frontyard. “I was scared,” he said later.

Another neighbor came from a few doors down, at Susana’s request, and took over talking to the dispatcher. Like Zamora, she spelled Keyser Drive.

The woman grew exasperated trying to communicate cross streets. She checked the mother for a pulse and inquired about the rescuers.

“They’re not on their way?” she asked the dispatcher.

The woman and another neighbor decided to turn Susana’s mother over.

“Oh dear. . . . Her tongue is hanging out, her lips is blue,” the woman said.

In the distance, more than a half-hour after Zamora placed his call, the wail of sirens could be heard.

Firefighters hurried into the home. Susana tried to describe what happened but her words ran together.

“Nobody’s done CPR or anything,” the woman cut in.

On the phone, the dispatcher signed off.

“I’m going to let you go. They’re going to help you.”

Finau was rushed to a hospital, where she was pronounced dead.

Lawsuit filed

“I never thought it would take so long,” Zamora said recently, pulling out the silver Sprint phone he used to dial for help that day.

An investigation by the San Joaquin County Emergency Medical Services Agency, which oversees 911 dispatching in Stockton, concluded that proper call-tracking information could have helped avoid the delays and confusion over Susana’s address.

“You would have known it was in the city limits of Stockton, rather than in the middle of the county,” said Dan Burch, who heads the agency.

The investigation report did not address whether a faster response would have saved Susana’s mother, who, according to the coroner, died of a heart problem, hypertension and kidney failure.

The report found fault, however, with the local dispatch center, saying that it lacked updated mapping software that would have helped, and that the dispatcher failed to consult other maps that were available.

A spokeswoman for Sprint Nextel, Stephanie Vinge-Walsh, said the carrier was unable to trace what happened with the call, one among millions it handled in the last year. Because of the size and complexity of the state’s wireless network, she said, it was impossible to say what might have caused a failure to deliver location information that day, or whether her company’s equipment was a factor. “We constantly monitor the performance of our 911 system” and fix problems as they arise, she said.

Susana’s family has filed a wrongful death suit against the county and the private firm that operates the dispatch center.

On a recent day, the girl sat quietly in her living room as family members prepared for a traditional Tongan celebration marking the one-year anniversary of Finau’s death.

A life-size photo of Finau, smiling in a long, floral-print dress, was propped against the wall. It was adorned by a ring of white, plastic gardenias, her favorite flower.

The 47-year-old woman had been the matriarch and breadwinner for the tight-knit family of five children and two grandchildren.

When she wasn’t working as a landscaper, family members say, she was leading Bible studies or doing volunteer work for her Tongan Assembly of God church.

“She was the one holding everybody together,” daughter Murrieta Tupou said.

Susana may have been hardest hit. The girl has received counseling at school but still has trouble talking about what happened.

“My mom fell off the couch,” she told visitors.

Then she began to cry, burying her face in her sister’s shoulder.

Times researcher John Jackson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.