Pope John Paul II’s compassion for Jews on display at Skirball

As a young boy in Poland before World War II, Karol Jozef Wojtyla possessed an uncommon warmth for an often reviled group of outsiders -- Jews.

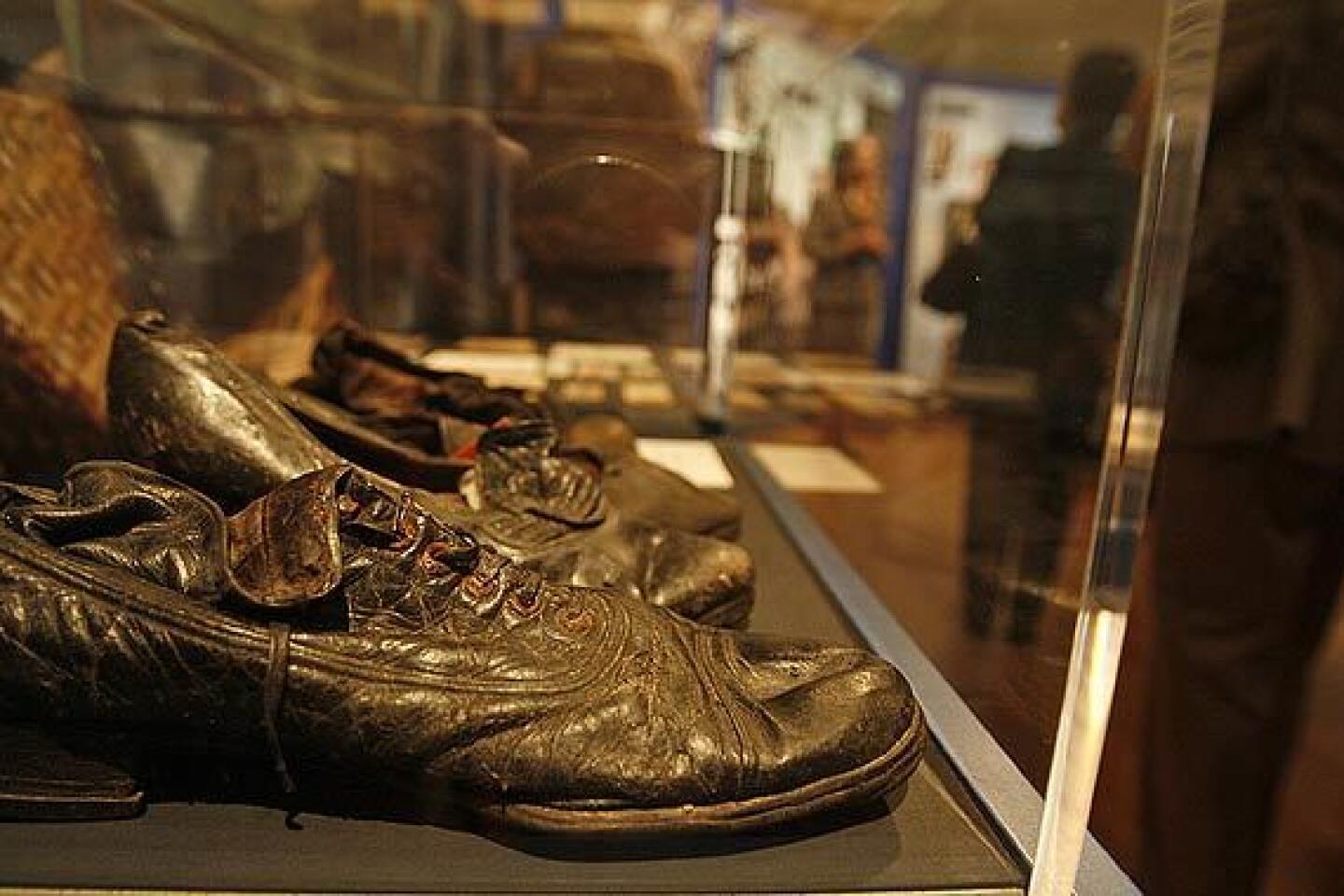

Like most others in his hometown, Wojtyla was Catholic. But he counted Jewish children among his friends -- attending school with them, even playing goalie on their soccer team.

Wojtyla was speechless when one of them, a fellow actor in drama club, informed him that she was leaving to escape looming anti-Semitism.

Decades later, those early experiences and friendships would have a dramatic influence on Wojtyla -- the future Pope John Paul II.

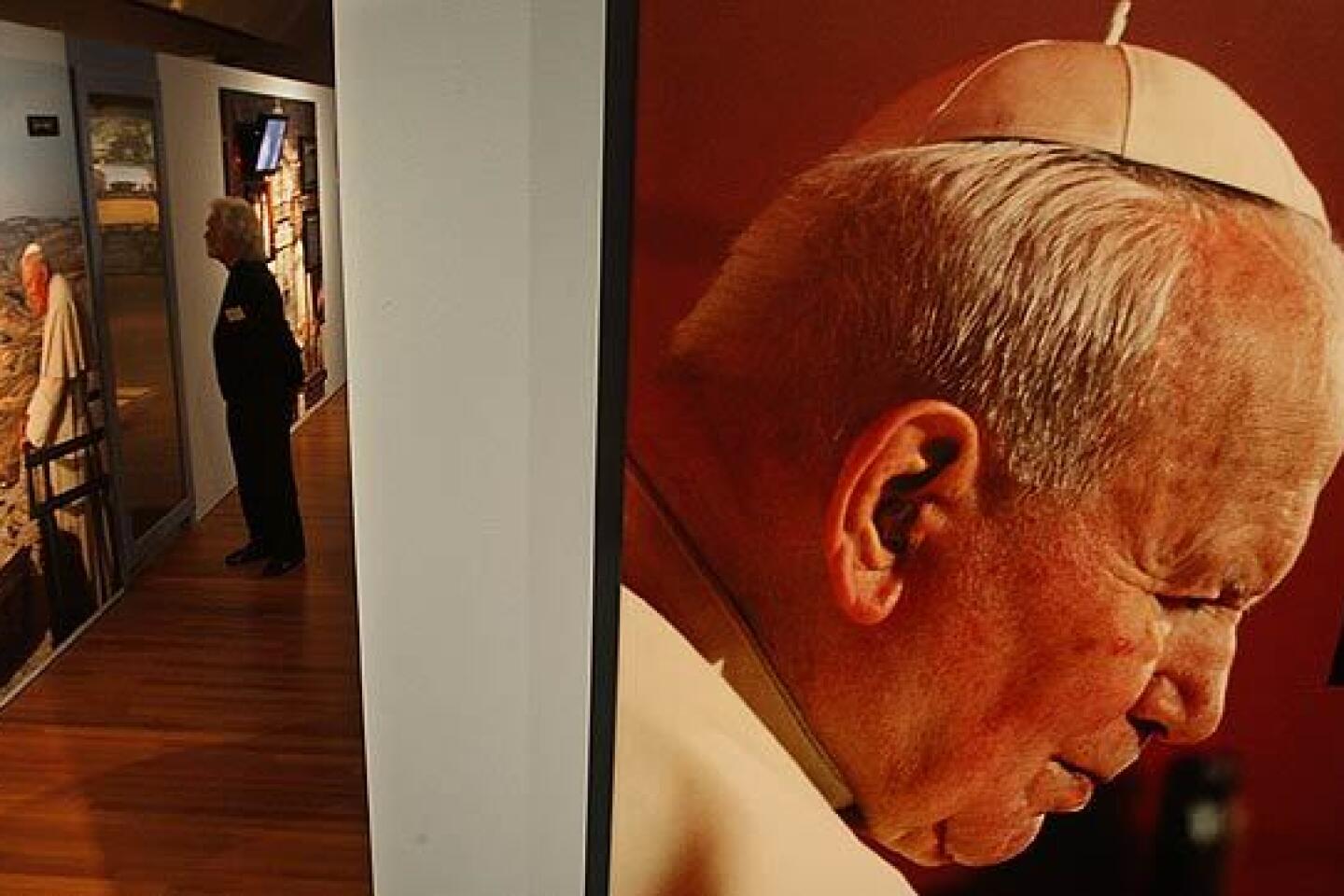

The Jewish threads of John Paul II’s life, as a new exhibit at the Skirball Cultural Center shows, shaped much of his legacy during 26 years at the head of the Roman Catholic Church.

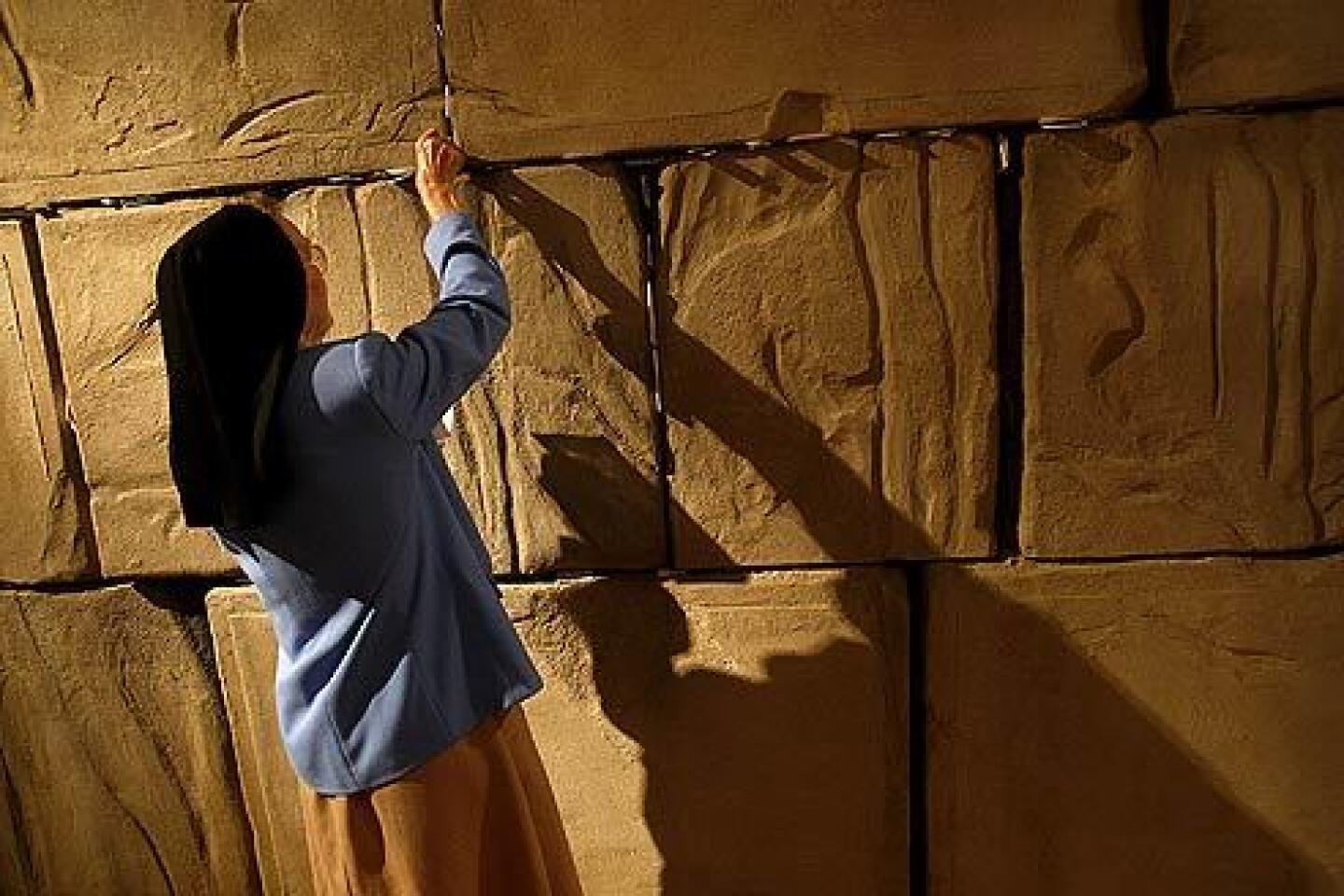

John Paul II was the first pope to pay an official visit to a synagogue, to formally recognize Israel and make an official trip to the Jewish state. He also was the first to pray at the Auschwitz concentration camp in his native Poland and to formally repent for the Catholic Church’s failure to adequately recognize and react to the Holocaust, according to one of the scholars who assembled the exhibit.

“There is no single person in history who has done more to foster dialogue among religions than John Paul II,” said James Buchanan, director of the Brueggeman Center for Dialogue at Xavier University in Cincinnati and one of the creators of the exhibit “A Blessing to One Another.” (The show was also produced by the Hillel Jewish Student Center in Cincinnati and the Shtetl Foundation in New York.)

But John Paul II’s efforts were more overture than finale in the long arc of Catholic-Jewish relations, scholars and religious leaders agree.

Some Catholic and Jewish leaders who previewed the exhibit last month warned that the healing inspired by the pope will continue only if others take up his call for reconciliation.

“We need to keep fostering these types of relationships,” said the Rt. Rev. Alexei Smith, ecumenical and interreligious affairs officer for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles. “We need to expand them.”

Rabbi Mark S. Diamond, executive vice president of the Board of Rabbis of Southern California, said both sides must strive to overcome a tortured history, which has seen Jews blamed for Jesus’ death, followed by 2,000 years of hostility and persecution.

“There is still plenty of work to be done,” Diamond said. “How do we translate our fervor for our own faith into the recognition that we are all God’s children? That is the great challenge we face today.”

As the exhibit shows in photos, videos and quotations from the pope, it’s the same challenge John Paul II confronted from his earliest days.

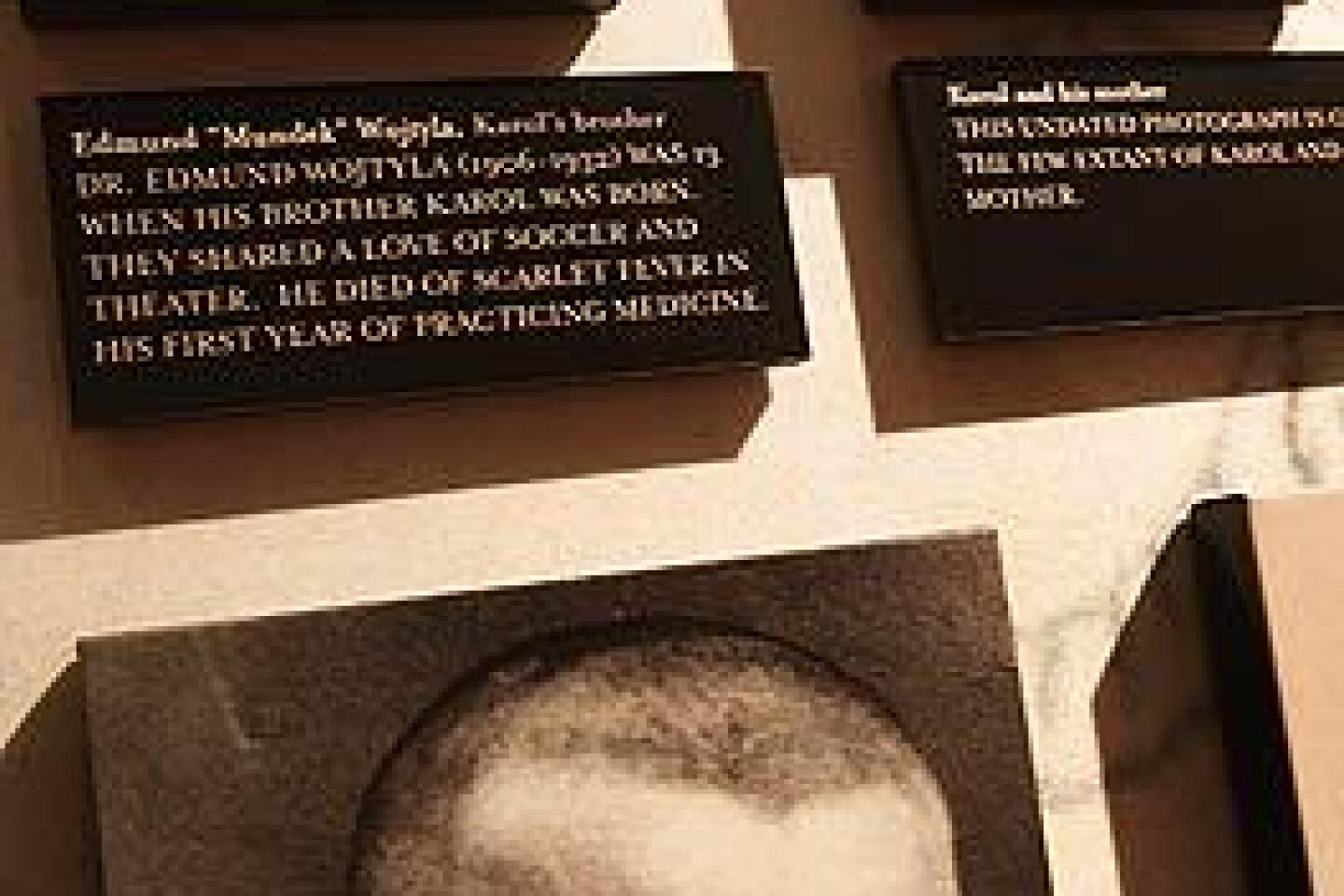

As a boy, Wojtyla lived in an apartment building owned by a Jewish family in the town of Wadowice, not far from Krakow and the town of Oswiecim, known to most of the world by its German name, Auschwitz.

One of Wojtyla’s closest friends was a Jewish boy named Jerzy Kluger. On one occasion, Kluger, excited to report the news that both had passed their high school entrance exams, ran to the Church of Our Lady as Wojtyla was serving Mass.

A woman approached Kluger as Mass ended, arousing Wojtyla’s curiosity. He asked Kluger what the woman wanted.

“Maybe she was surprised to see a Jew in church,” Kluger responded.

“Why?” Wojtyla asked. “Aren’t we all God’s children?”

Kluger survived the Holocaust and Soviet deportation to a forced labor camp in Siberia, but most of his family perished. He reunited two decades later with Wojtyla, then archbishop of Krakow.

Wojtyla was elected pope in October 1978. At his first papal audience, he received Kluger and his family ahead of 3,000 other guests, leading one Italian newspaper to declare: “Pope Grants First Audience to Hebrew Friend.”

The pope’s views were also shaped by his experiences under Nazi occupation. Jews from Wadowice and Krakow were forced into ghettos, with most eventually dying in massacres or in concentration camps. Meanwhile, Wojtyla had to flee Krakow, where he had been studying linguistics, Polish culture and philosophy at Jagiellonian University. Later, he was required by the Nazis to work in a quarry while he secretly pursued the seminary.

“My priestly vocation took definitive shape . . . against the backdrop of the terrible events taking place all around me in Cracow, Poland, Europe, and the world,” he wrote years later. “I experienced directly only a small part of what my fellow countrymen experienced from 1939 onwards. I think especially of my classmates in Wadowice, close friends, some of whom were Jews.”

After the war, Wojtyla served as a priest in Krakow before advancing through the clerical ranks to become archbishop in 1964. He attended the Second Vatican Council, the gathering of leading Roman Catholic clergy from 1962 to 1965 that, among other things, adopted the famous Nostra Aetate doctrine, which sought to usher in a new relationship with non-Christian religions, particularly Jews.

The council said that “Jewish authorities and those who followed their lead pressed for the death of Christ,” but it added that his death “cannot be charged against all Jews, without distinction, then alive, nor against the Jews of today.” And it said the Church decried anti-Semitism and persecution of Jews. Theologians and religious scholars say that John Paul II acted on those tenets, noting his visit to the Great Synagogue of Rome in 1986 and his remarks before Chief Rabbi Elio Toaff.

“With Judaism we have a relationship which we do not have with any other religion,” the pope said. “You are our dearly beloved brothers, and in a certain way, it could be said that you are our elder brothers.”

The exhibit’s creators also note John Paul II’s expressions of sorrow over the Holocaust and his bridge-building efforts, including one on the 50th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. In a letter written upon the occasion, he pointed out the similarities between the two faiths -- using words that would provide the name for the Skirball exhibit.

“As Christians and Jews, following the example of the faith of Abraham, we are called to be a blessing for the world,” he wrote. “This is the common task awaiting us. It is therefore necessary for us, Christians and Jews, to be first a blessing to one another.”

“A Blessing to One Another” will be at the Skirball Cultural Center, 2701 N. Sepulveda Blvd., Los Angeles, through Jan. 4.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.