In Torrance Police Department, forensics is women’s work

For about a year, the forensics unit has been all female — perhaps a sign of ‘the CSI effect.’ And their results are impressive.

- Share via

Gabrielle Wimer was nine months pregnant and working a crime scene when she found the closest thing to a smoking gun for a forensic specialist: a clean, detailed fingerprint.

"I was like, 'Oh, I got a beautiful print right here,'" she recalled. "And I turned and my belly just wiped it off."

That was it, she said: "I'm done until I have this baby."

Now almost 3 years old, Wimer's daughter is still too young to understand her mother's job. All she knows, Wimer said, is that it's for the police. "Police," she'll say. "Mama's work."

Wimer is a forensic identification specialist for the Torrance Police Department — one of seven experts in charge of collecting evidence from scenes, analyzing it for clues and helping detectives close their cases.

And for about a year now, the team has been made up entirely of women.

Law enforcement is dominated by men. According to the FBI's most recent statistics, only 11.9% of officers nationwide in 2012 were women.

Science is also dominated by men, who tend to collect higher degrees and higher salaries than women.

By all accounts, forensic science — the marriage of the two — should be the same. Instead, more women are finding jobs, filling classrooms and creating careers for themselves in the field. In places like Torrance, they're not just catching up to their male counterparts, they're outpacing them.

The Torrance Police Department once used sworn officers to handle forensics duties. Cops learned on the job, usually working the unit for about two years before they moved to another assignment.

But in February 2010, the rotating officers were replaced by civilian experts with years of experience.

Donna Brandelli was brought in to jump-start the civilian unit. She had spent two decades with the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department, first as a dispatcher and then as a forensic specialist.

She steadily built up the Torrance division, developing protocols, finding new equipment and improving communication between officers and her civilian crew.

There were challenges at first.

Wimer holds a piece of broken glass found at a burglary scene. Glass is ideal for capturing suspects' fingerprints -- unless they were wearing gloves, as appeared to be the case in this instance. More photos

"It's hard enough coming in here as a civilian in a law enforcement environment, and then to be a female civilian?" Brandelli said. "We had to break through that."

When the women started showing up at crime scenes, some detectives were skeptical, members of the team said. A few were reluctant to hand over the scenes for processing.

But soon the department started seeing an increase in cases closed with the help of forensics. Detectives began stopping by the lab to congratulate — and thank — the unit for its work.

"It completes our investigative unit. The results are right there: People are getting arrested for crimes they're committing in our city," said Sgt. Robert Watt. "Those forensics people are just as relentless as our detectives."

The radio crackled as Tina Bazzo drove to her first scene of the day. A man had called police after spotting three people trying to break into his neighbor's home.

They don't necessarily want to be the gunslinger.”— Forensic specialist Donna Brandelli

The homeowner took her to the backyard. A window screen had been flung onto the grass; a large shard of glass lay nearby.

Bazzo snapped a few photos before she began to dust for prints, her brush twirling black powder onto the broken glass.

"This is the ideal surface for prints," she said. "So if we're gonna find them, we'll find them."

No luck. A pattern on the glass indicated the would-be burglar was wearing gloves.

"It's not like the movies, huh?" the homeowner half-joked.

"I wish," Bazzo said. "I'd be solving this thing in an hour."

The 30-year-old was 10 when she got her first fingerprinting kit, a Christmas present from a family friend. She dusted everything in sight.

"I love my job," she said. "I couldn't imagine doing anything else."

Sometime in the last decade or so, more women began studying forensic science. Some credit the so-called "CSI effect," saying strong female characters in crime television shows — think Abby Sciuto on "NCIS" — have inspired more young women.

"Women see these characters in 'CSI' and female leads of scientists who do this job … it's cool for them to say, 'I want to be like Abby,'" said Jenifer Smith, a retired FBI special agent who now teaches forensic science at Penn State University. "It really does seem to make a difference, seeing women in lab coats doing things."

Smith guessed that roughly 75% of the university's forensic science program is female — on par with what schools are seeing nationwide. One 2009 study estimated that 78% of the students enrolled in such programs were women.

Forensics, Brandelli said, offers women the chance to work in law enforcement without becoming police officers.

"They want to be in public safety, they want to help, they want to do something to help their community or to solve crime," she said. "But they don't necessarily want to be the gunslinger."

"It's brains," said Krishna Patel, one of the Torrance unit's fingerprint experts. "Not brawn."

Cristina Pino, the department's newest hire, said it was hard to explain why she was drawn to the work.

"One day I was reading some stuff about forensics and something about forensic anthropology, and I said, 'Oh my God, that's amazing,'" the 35-year-old said. "It's something deep in me, something I love."

But in Pino's native Italy, only sworn officers could work in forensics, she said. So after earning her master's degree in criminology, she headed for the U.S., leaving her husband and other loved ones behind.

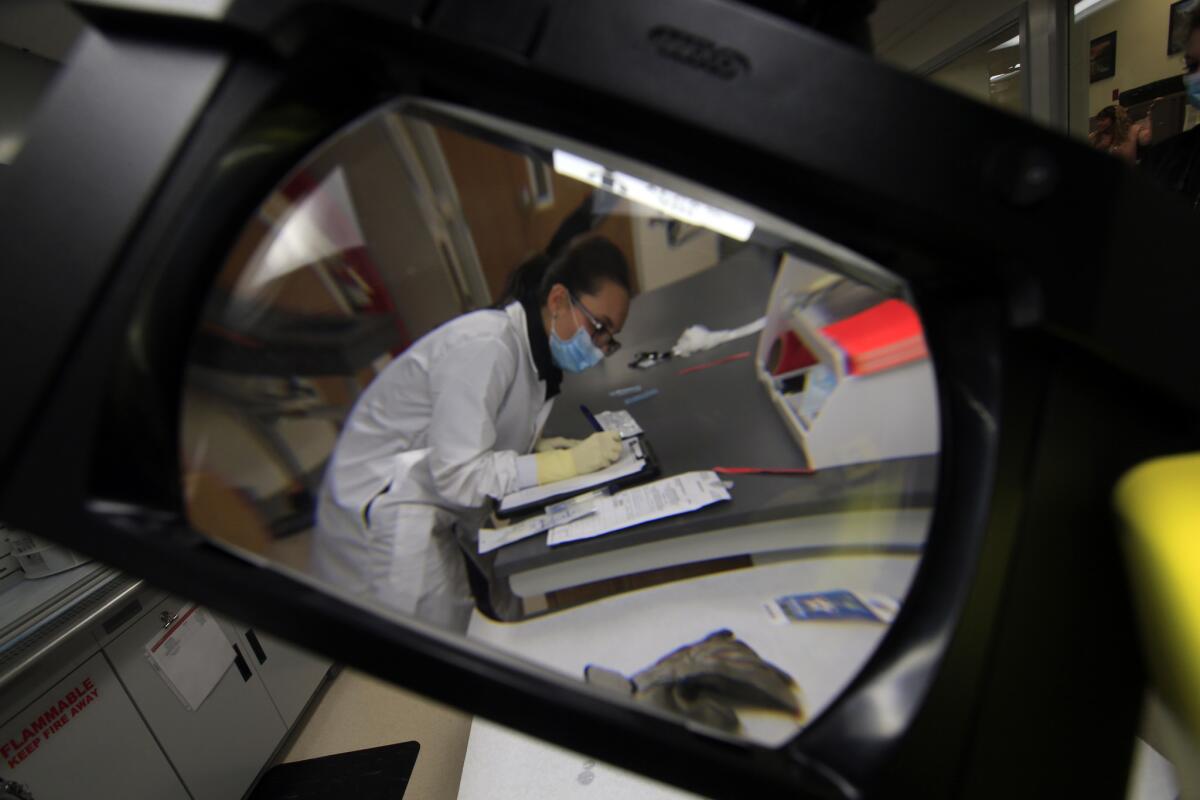

Pino works in the lab after collecting evidence at the site of a burglary. More photos

Pino spent two years learning English, then six months taking forensics classes — all the while working at a restaurant and flying back to Italy whenever she could. After internships with Los Angeles County and Beverly Hills, and a stint at the Long Beach Police Department, she was hired by Torrance in August.

Her husband moved to the U.S. about two years ago.

"I didn't give up," she said, smiling. "This was going to be my job. And I'm here now."

The job isn't easy. There's no room for error. The smell of death from a homicide scene can linger for days. And the hours are long and erratic.

For the specialists who are mothers, that can be particularly difficult.

Brandelli worked for the much busier L.A. County when her daughter was young. Because her husband was a firefighter, she couldn't always drop everything at home to go to a crime scene.

"It was the sworn male deputies who were the ones making the biggest comments.... 'Why aren't you handling this call?'" she said. "I couldn't just leave my sleeping child in bed at 2 o'clock in the morning."

But sometimes her experience as a mother came in handy.

No more so than when officers struggled with a teenage suspect who wouldn't follow directions. "Can you go take care of it, Donna?" the officers asked.

When Brandelli emerged from the room, they asked how she'd gotten the suspect to cooperate.

"You know that look that only your mom can give you?" she said. "That's the one he just got."

Team members, from left, Christina Pino, Gabrielle Wimer, Krishna Patel, Carrie Harris, Nicole Salim and Tina Bazzo share a light moment with their boss, Donna Brandelli, foreground in pink. Brandelli was brought in to jump-start the civilian unit in 2010 and has assembled an all-woman team that handles all of the forensic work for the Torrance Police Department. More photos

In the four years that Brandelli has overseen the Torrance forensics unit, her specialists have responded to more than 4,700 calls, collecting thousands of prints and nearly 1,000 DNA samples. The result, police said, was a 400% increase in DNA evidence submitted, with more than 500 suspects identified.

The department honored the unit at a luncheon last month, hailing its work as a key tool in combating crime across the city.

But for the women, it's not just about the numbers. They smiled as they shared other stories of their success: reuniting victims with stolen property, or exonerating someone falsely accused.

"It makes me feel proud, being a female in the profession that I am in," Patel said. "I needed to prove not just to people around me but to myself, 'You know what, I can do this, and I can reach a top level and I'm going to do it.'"

Brandelli is leaving the team in March, moving back to the East Coast with her husband, who is retiring. She's leaving behind a nickname, one she and other women heading forensic units came up with:

The fabulous forensic females.

Follow Kate Mather(@katemather) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

Bobsled designer races to craft a U.S. winner

You’re looking to gain hundredths of a second. That’s all it takes to win.”

Son of a Holocaust survivor searches for a lost Nazi diary

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.