Few can reconcile Leland Yee with the charges against him

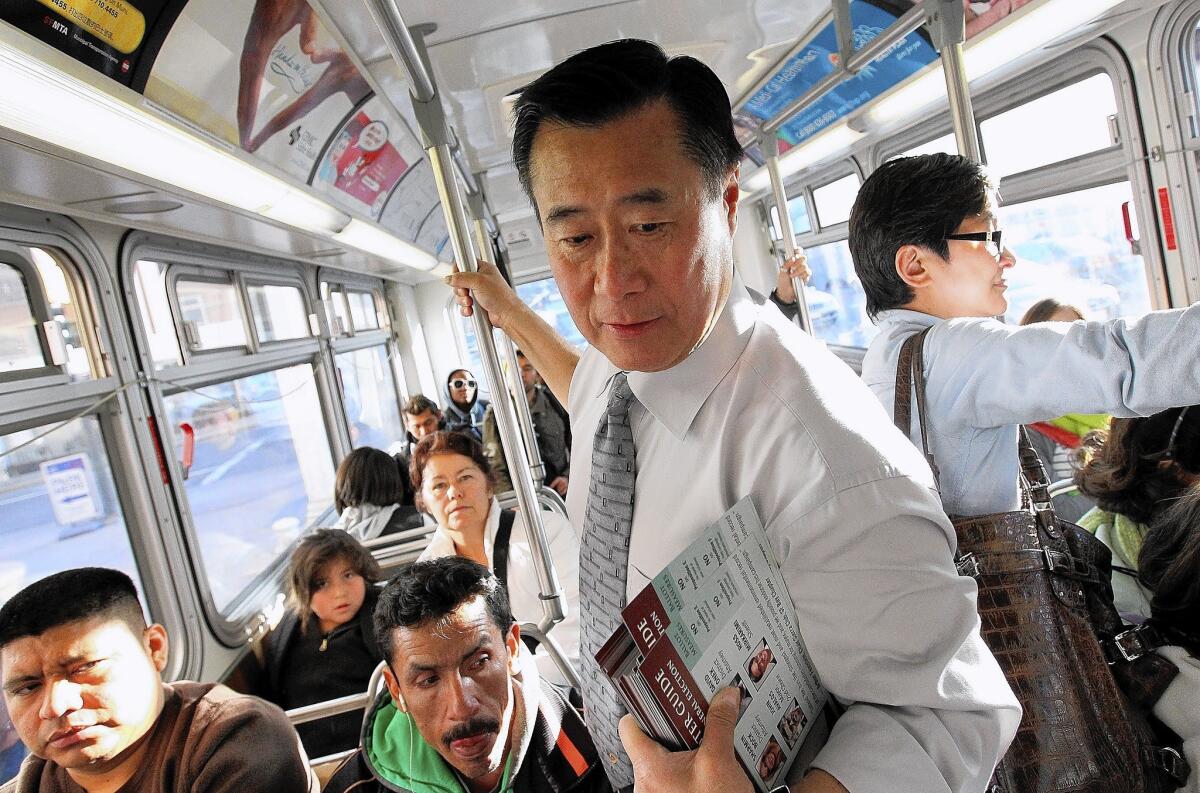

SAN FRANCISCO — For more than two decades, Leland Yee climbed the political ladder in San Francisco.

A child psychologist turned politician, Yee straddled opposing camps in the city’s bare-knuckled political fights, appealing to both right and left and catering to constituents with a strong, attentive staff.

Elegant in appearance and charming in manner, he courted financial contributors and built a reputation as a canny pol with an enviable knack of identifying the high-profile issue of the day and then weighing in before a thicket of cameras.

When Yee was arrested last week on suspicion of public corruption and gun trafficking, few could reconcile the man recorded by undercover FBI agents with the familiar face on the local news.

Yee had won awards for espousing open government and gun control, but a federal charging document quoted him offering to trade political favors for cash and campaign contributions and broker an illegal shipment of automatic weapons and possibly rocket launchers. Yee was depicted as frenzied in his search for campaign money.

“There is a part of me that wants to be like you,” Yee told an agent posing as an arms buyer, according to the document. Agents said Yee had confided he was unhappy with his life.

His colleagues in Sacramento said the man they knew did not fit the portrait built by federal prosecutors.

“It was night and day, yin and yang,” said former Sen. Gloria Romero, a psychologist herself. “It defies reality.”

In San Francisco, where his opponents over the years had branded him a chameleon, the reaction was more muted.

“He would play to both sides of the room, though not at the same time,” said David Lee, a political science lecturer at San Francisco State University who has known Yee for years. “He was a trail-blazer, but the politics in the Asian American community and California have changed. He has been trying to hold on to power and stay relevant in a fast-changing time.”

Yee, 65, has withdrawn as a candidate for secretary of state and has been suspended with pay from the Legislature. Federal prosecutors announced Friday that a federal grand jury had returned indictments against Yee and 28 others, including a reputed Chinatown gang leader. Yee is free on $500,000 bail.

Paul DeMeester, his friend and former attorney, has questioned why it took agents three years of undercover work to arrest Yee.

“There is only one true Yee,” DeMeester said, and it is not the one federal prosecutors portrayed. Listening to the FBI tapes, instead of reading the cold transcripts unveiled last week, will reveal “how it is said, the intonations — Is there boasting? Is there joviality?”— and provide a truer picture of what happened, the lawyer said. (Yee’s lawyer, James Lassart, could not be reached for comment.)

Yee’s pro-union and gun-control stances won him support in San Francisco’s progressive community, yet he appealed to conservatives by siding with landlords and business.

In Sacramento, Yee’s votes at times mirrored the interests of his campaign contributors. California allows lawmakers to seek campaign money from donors affected by pending bills, and it is not uncommon for lawmakers to vote in line with those checks. Yee has said his votes reflected his conscience, not his campaign pocketbook.

In January 2006, then-Assemblyman Yee joined five Republicans in voting against a bill to ban the chemical bisphenol A from toys and other products for young children. The bill failed in committee by one vote. Former Assemblywoman Wilma Chan told The Times that Yee had promised to vote for her bill. Days before the roll call, he reported receiving $1,000 from Dow Chemical, manufacturer of bisphenol A.

Yee received $12,700 from plastic bag maker Hilex Poly, including $6,800 in three months in 2013 after he opposed a proposed ban on plastic grocery bags.

Yee’s power base in San Francisco was in the city’s more conservative west side, not Chinatown. He was considered a political lone wolf, eschewing Democratic Party gatherings in the city and at times defying party leadership in Sacramento.

Over the years, he had minor brushes with the law reported in media accounts, but none resulted in criminal prosecution. San Francisco police twice stopped him in 1999 because they believed he was trawling for prostitutes. Yee was let go without any charges. He was arrested in Hawaii in 1992 for allegedly trying to steal a bottle of suntan lotion but left the state without being prosecuted.

His political career began with his election in 1988 to the San Francisco Board of Education. He later was elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors and the state Assembly and became the first Chinese American to win a seat in the state Senate. He now represents part of San Francisco, where he lives, and San Mateo County.

During his early days in politics, Yee aligned himself with the city’s growing population of middle-class Chinese Americans, who felt neglected by the city’s liberal establishment. Asian parents back then complained the school assignment process hurt highly qualified Chinese Americans by denying them entrance to the city’s top public schools. Yee spoke up for them.

With an eye on future office, Yee worked tirelessly for former Mayor Willie Brown Jr. in the city’s 1995 mayoral race, said Ed Lew, who also helped in the campaign. Yee’s wife sometimes stopped by with their children, who did their homework while their father worked. Lew said Yee helped Brown capture the Chinatown vote.

But Yee felt “jilted” when Brown appointed another Asian American to a vacancy on the Board of Supervisors, said David Lee, the San Francisco State lecturer. Yee eventually ran himself, winning a citywide vote and later a district election.

When he was a supervisor, Yee helped lead an effort to rebuild a city freeway destroyed in an earthquake. A coalition of Chinese Americans, unions, merchants and real estate interests passed a ballot measure in favor of the freeway, which supporters argued would bring jobs and reduce traffic on congested city streets. Brown and the city’s more liberal neighborhoods opposed it.

Although San Franciscans later rescinded the measure, its passage was “a watershed moment,” David Lee said. “Chinese Americans put on a ballot measure and won a campaign for the first time. Leland was one of the leaders of the movement.”

His career appeared aimed at one day becoming San Francisco’s mayor, and Yee ran in a crowded field in 2011. Yee felt it was “his time,” and he amassed support from unions and developers, Lee said. But he lost to another Chinese American, Ed Lee, who had never before run for office and had the support of the political establishment and Chinatown.

Nathan Ballard, a political strategist who supported Lee, said Yee’s tendency to be “all over the map” on issues deprived him of a “clearly defined political brand.” Yee spent much of the campaign trying to portray Lee as corrupt in “hit pieces,” Ballard said, and received support from progressive voters who saw Lee as part of the Willie Brown machine. But it was not enough.

Yee’s mayoral defeat left him with broken dreams and a campaign debt of $90,000.

Born in China, Yee immigrated with his family to San Francisco when he was 3. He earned degrees from UC Berkeley and San Francisco State and a doctorate in child psychology from the University of Hawaii. He and his wife, Maxine, have been married for 42 years. They have four children.

Yee’s colleagues in the Legislature described him as smart and diligent. They said he rarely, if ever, spoke about personal matters.

Sen. Lou Correa (D-Santa Ana), who has known Yee for more than a decade, said his training as a child psychologist fueled an interest in advocating for children’s issues. The two men traveled to China on a cultural and trade mission, and Correa knew Yee as someone who was “always joking, very jovial.” Correa said he remains baffled by the accusations against Yee.

“That was a Leland Yee I had no idea even existed,” Correa said. “This was something I had never seen.”

Dolan reported from San Francisco, McGreevy and St. John from Sacramento.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.