L.A. schools’ iPad watchdog committee set to disband

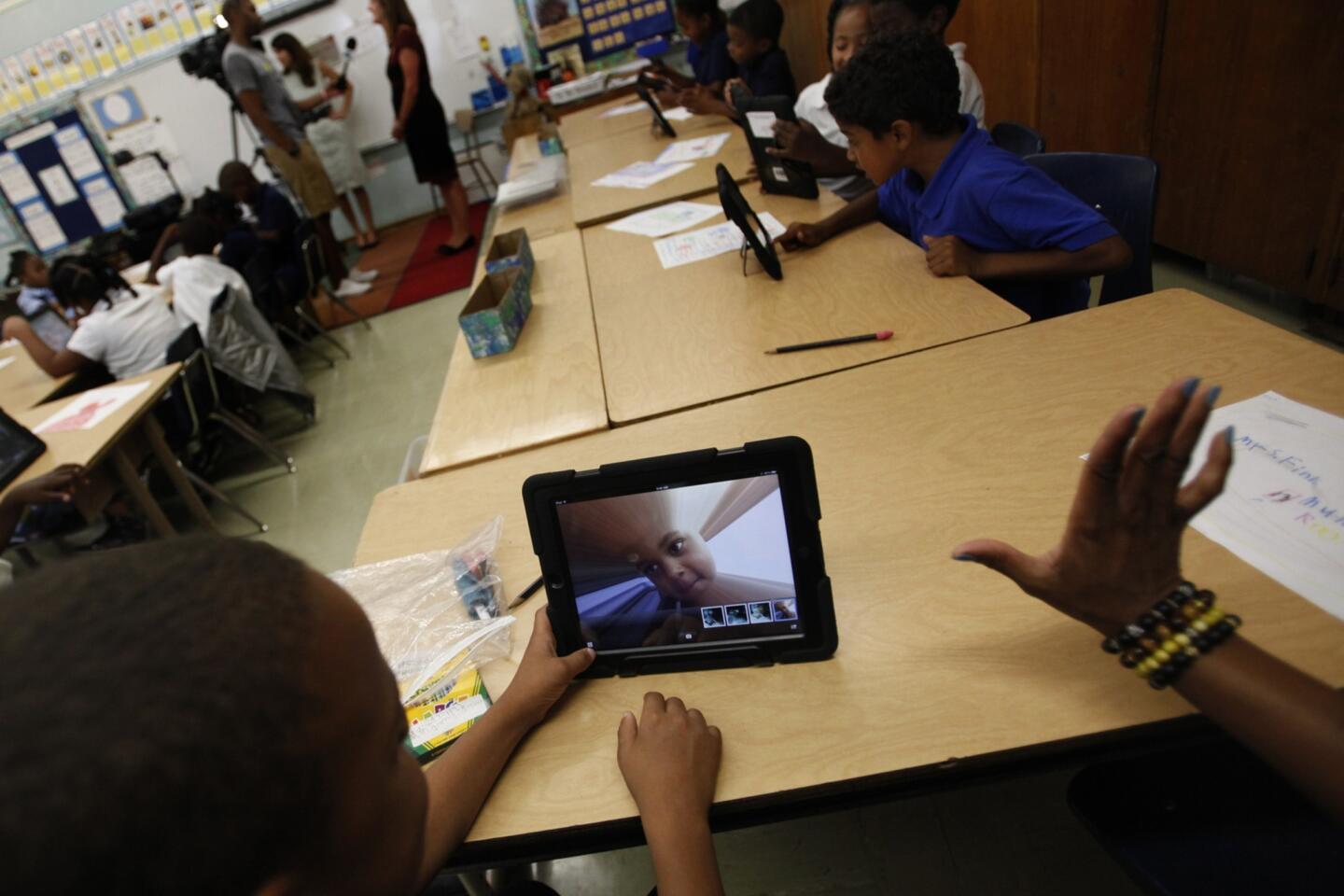

The watchdog committee for the Los Angeles school district’s $1-billion iPad program is scheduled to fold, raising questions about oversight of the ongoing effort to provide every student, teacher and administrator with a computer.

The decision to disband the panel as of April was announced last week by Board of Education President Richard Vladovic.

“I think there needs to be a conclusion of some sort,” he said in an interview. He also insisted that all necessary oversight would continue.

School board committees, the purview of the president, are intended to allow members to publicly ask in-depth questions and raise concerns about policies and proposals for which there isn’t enough time during regular meetings. They also can be used to change recommendations before they reach the full board.

Critics consider the panels redundant to the board’s work, a prodigious waste of staff time. Previous board president Monica Garcia had dissolved them.

Vladovic said he intended to strike a middle ground, making most committees temporary, with a defined, finite purpose. Even so, his announcement caught Monica Ratliff, who chairs the watchdog technology committee, by surprise.

Ratliff’s panel bears the cumbersome name of Common Core Technology Project Committee — Common Core refers to new state learning standards in math and English. The district intends to reach these academic goals through curriculum installed on the iPads, although that is not a state requirement. The iPads also will be used for new state tests, which eventually must be given by computer.

The 12-member panel consists of appointees from the community and district-related organizations, including employee unions.

Some have complained that the panel has impeded an innovative effort that would otherwise have progressed further and faster. The iPad program was envisioned as a national model, and senior officials, including Supt. John Deasy, defend the overall effort as superlative.

Others credit Ratliff’s group for slowing a project that was being carried out too hastily.

“It’s very clear that the rollout had some problems and the district has been well served by admitting there were problems and beginning to address them,” said Ratliff. Also, “It was really important for the public to have their questions asked publicly and, to a degree, answered.”

The panel has raised or unearthed issues that senior administrators sometimes fumbled, providing incomplete, inaccurate and conflicting information. At one point, for example, they said the iPads didn’t need keyboards, then later that they did, then that they knew all along that keyboards would be necessary.

At another juncture, an administrator said the district owned the curriculum on the iPads; later, officials conceded that, in fact, the curriculum was licensed for three years.

Just last week, Ratliff related the latest of her unsuccessful attempts to get access to the full curriculum, which was selected based on incomplete samples.

The work of the committee also influenced changes to the project, such as the addition of a fuller evaluation and a trial of laptop computers for older students.

Ratliff said that continued scrutiny remains necessary, but she did not criticize Vladovic’s move.

Vladovic wants her to take the helm of the curriculum and instruction committee, which was left without a leader when board member Marguerite Poindexter LaMotte died in December. Vladovic said the coming months will bring crucial decisions about instruction that will, at times, overlap with the computer issues Ratliff has been overseeing.

Deasy said he had no comment about the evolving committees, calling it a board issue. But in the past he has expressed concerns that the panels consume too much staff time.

Other elements of oversight remain in place. The school district’s inspector general is examining the process that led to the computer contract, which was intended to supply more than 570,000 iPads at a cost of $768 apiece.

The board also will commission an evaluation of the computers’ effect on student achievement.

Because the project is being paid for with voter-approved school-construction bonds, a separate committee, which oversees bond spending, also will continue with limited jurisdiction.

For years, the bond oversight group habitually supported staff recommendations. For the computer effort, however, the panel balked when Deasy sought one-time blanket endorsement of the entire effort, even before vendors began bidding for the work.

The bond panel insisted on a right to review each major expenditure of bond funds. The result is that it has examined the iPad project each time officials asked for substantial additional funding. Last week, for example, Chairman Stephen English challenged the district’s analysis of how many iPads would be needed for upcoming state standardized tests.

Decisions by the bond panel are not binding on the school board, but district officials have rarely departed from its recommendations.

Last week, however, was different. Materials from the most recent meeting of the bond oversight panel were not included in the information packet prepared for the board and the public. These materials included support for the panel’s analysis that fewer iPads were needed.

Deasy stood by his own numbers, and, in the end, the board gave him the discretion to buy as many iPads as he felt would be necessary.

Scott Folsom, a member of the bond committee, said he is concerned by Vladovic’s move to disband Ratliff’s panel. But he said he understands that it was not meant to be permanent.

“If Ratliff produces a report and the committee is dissolved, that is that,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.