At 99, psychoanalyst still has a lot on her schedule

- Share via

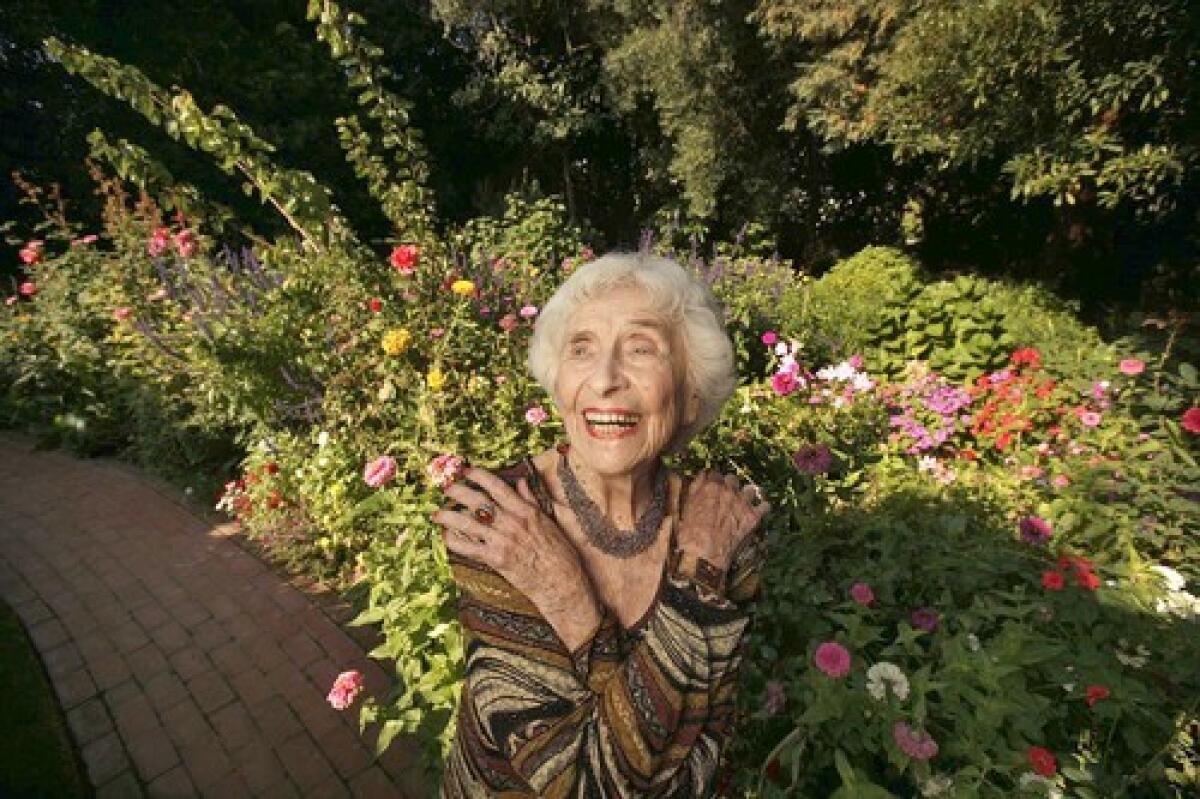

She answers the knock at the door, smiles exquisitely, floats through the afternoon light of her Brentwood home with casual grace.

It’s another full day for Hedda Bolgar, who sees patients four days a week, teaches on the fifth day, drives a Prius, is planning a trip to New Zealand, and needs to get through this interview before 5 p.m., when her personal trainer arrives.

She turned 99 last month.

“I was put on this Earth to accomplish certain things,” says Bolgar, a psychologist and psychoanalyst. “I’m so far behind, I can never die.”

Bolgar takes me to the office where she sees her patients. One of them is 88, another 84. Several of them are therapists themselves, and whatever burden they carry into this room -- the loss of a spouse, regret, guilt, fear of death -- Bolgar knows something about the experience.

“I’ve lived through revolutions, famine, war. Things like that,” she tells me.

She delivers her lines as if reading from a great novel that makes poetry of history.

At age 5, for instance, while she was vacationing on the Baltic Sea, the Austrian archduke was assassinated:

“There was a war, and I had vanilla ice cream for lunch.”

And later, after completing her PhD in Austria:

“I left Vienna the day Hitler came in.”

And then on to Chicago for more training, then New York, where she got married, and finally to Los Angeles, where she has made her home since 1956.

I hadn’t visited Bolgar to be analyzed, or at least I didn’t think I had. But by the time I left, she’d gotten me to confess that I often feel harried. Maybe a Valium would help, I said. Better yet, she countered, maybe I should examine why I allow myself to get so bunched up. Her couch looked comfortable, but she told me she no longer takes new patients. She’s afraid they’d come to rely on her, and, at close to 100, who knows how much longer she’ll be in business?

The real reason for the visit was that I’ve been writing a lot lately about seriously ill members of my family, and others who have been forced to make peace with mortality. Who better to provide insight and uplift than a 99-year-old dynamo who says life has never been better than it is right now?

Bolgar says her parents, who were European journalists, told her that when she was in the womb, they discussed dream interpretations with a Swiss friend by the name of Carl Gustav Jung. They also told her that family tradition obligated her to address society’s unmet needs.

“I started a lot of things at 65,” says Bolgar. That was just one year after the death of her husband of 33 years, a political scientist.

Los Angeles needed better training for analysts, Bolgar thought, and too many people were unable to get treatment because of the high cost. So in the 1970s she founded the Wright Institute of Los Angeles, a nonprofit mental health training and service center, and co-founded the Los Angeles Institute and Society for Psychoanalytic Studies. In 1974, she started the Hedda Bolgar Psychotherapy Clinic, which still treats people who can’t afford help elsewhere.

The secret to a long and healthy life, Bolgar says -- aside from lucky genes -- is to be a citizen of the world. In her case, that has meant things like joining antiwar and anti-nuke marches on Wilshire Boulevard (yes, she was there in the ‘60s), and hanging a “Let Truth Be the Prejudice” poster just inside her front door for all guests to see.

“You need to be invested. You have to care about what happens,” she says, and her delicate fingers reach across a table for a business card from another group she works with: the Soldiers Project, which offers psychological counseling to soldiers and their families.

Bolgar has no computer. No BlackBerry. She is no prisoner of television, either, but has walls of books and can spend hours tending the “ocean of flowers” in her yard. And, partly because she’s been a vegetarian for 85 years, she gets an upset stomach thinking about the NRA poster girl on the GOP presidential ticket.

One of Bolgar’s longtime patients tells me she’d never heard of the therapist until a friend made a recommendation.

“You have to see Hedda,” said the friend.

“Who’s Hedda?”

“Hedda’s the best.”

And?

“Oh, my goodness,” says the patient, calling Bolgar brave, patient and strong. “She’s, well, very, very, very perceptive and very, very devoted . . . She carries herself with dignity and hope, despite her tremendous realism.”

This patient, whose name I agreed not to use, was so impressed with Bolgar that she became an analyst herself.

There’s so much depression, Bolgar says, attributing it in part to the false hope of pop culture and marketing. And then, she says, “there is this whole group of women who, when they get to be 60, become tremendously preoccupied” with appearance.

What about the men, I ask, thinking of Arnold’s Woody Woodpecker dye job and Joe Biden’s plugs.

Sure, Bolgar allows, but most of her patients are women.

I ask if she’s ever lost anyone.

“I had one patient who came to me after 20 suicide attempts and said to me, ‘I will probably do it again.’ ”

They worked together for four years, then the patient began cutting herself loose.

“She said, ‘Don’t sentence me to life. I can’t do it.’ ”

Even though Bolgar’s very spirit is an affirmation of life, she respected the patient’s right to make her own peace.

“We had a contract. I would not stop her.”

The patient missed an appointment. Bolgar called her house and a sheriff’s deputy answered. Yes, the patient was dead.

“He said, ‘Doctor, you need to talk to someone. You sound upset.’ ”

Bolgar was terrified on her way to the funeral, fearing that the patient’s family would hold her responsible. Instead, they lifted her burden.

“They said I’d given her the best four years of her life.”

Bolgar has a photo of Sigmund Freud in her office. “The master,” she calls him. We’re standing near the photo when she tells me about a problem she’s been working on since losing her husband 35 years ago.

“His mother was on the last transport to Auschwitz,” Bolgar says. “He never talked about it and here I am, an analyst, and people talk to me. I can’t quite forgive myself for not being able to get into it with him.”

I’m no analyst, but I wonder if her inability to break through to him is part of what keeps her trying to help others at 99.

Each patient reveals new truths, Bolgar tells me. She learns something about the world, something about herself.

Something that keeps her young.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.