Finding beauty and healing among the saints

- Share via

Sister Nuala Ryan’s shoes are wet with dew when she walks into the rec center. The place isn’t much to look at, all cinder-block walls, dusty curtains, a deflated balloon that’s been hanging from a ceiling vent for as long as anyone can remember. Church services will begin soon, right here. There is much to be done.

The service linen must be draped over the altar. Someone must fetch the box of miniature New Testaments from the back. Someone has dropped off four pretty sprigs from a bottlebrush tree; they’ll need to be dropped into little vases.

There are volunteers, local high school students spending their first day at Lanterman Developmental Center in Pomona. Be careful with the residents, Ryan tells the students. Many cannot move on their own. Their bones are weak; their muscles have atrophied. But don’t be afraid. “Let go of that,” she tells them.

Soon, the congregation arrives, 60 people, most in wheelchairs, most getting on in years, most with the mental ability of a small child. One asks Ryan, for the umpteenth time, to sign her autograph book. Ryan smiles kindly: “Thank you for asking.”

Another struggles to put on a tunic. Ryan watches him for a full minute.

“Would you like help?” she asks, finally. “Yeah,” he says.

“Comfortable?” “Yeah.”

“You look handsome.” “Yeah.”

A priest once asked her not how she does it, but why -- for 23 years, when she could have been elsewhere, when much of her flock cannot pray, or dance or sing. Where else, she asked him, could she walk each day among saints?

Hidden away in rolling hills between Diamond Bar and San Dimas, Lanterman is one of California’s oldest institutions for the developmentally disabled. It has been around since 1927, long enough for its residents to be called “imbeciles,” then “inmates,” then “patients,” then “clients” -- mirroring the nation’s efforts to devise increasingly dignified and sophisticated methods of caring for people with severe disabilities.

The newest model is community care, with more individualized treatment in smaller settings. The large institutions are being shut down, slowly and deliberately.

The challenges haven’t changed; 70% of the clients, suffering from cerebral palsy and from severe forms of autism and epilepsy, have an IQ below 14. It’s the size of the population that has changed; Lanterman, which had nearly 3,000 clients at its peak, has fewer than 500.

It will be years before Lanterman closes, but some long-term staffers have started to step down. In two weeks, Ryan will too. She is retiring, at 75, after nearly a quarter-century of service as a music therapist and, for the last 11 years, Roman Catholic chaplain.

Ryan is known on campus for putting together touching memorial services for clients. Deaths happen with some regularity, and she loves doing the services because she views them as a celebration of sorts, a glorious moment when clients are freed of a body that had imprisoned them.

Ed Bischof, a Lanterman psychologist, said he was floored when he attended one of Ryan’s recent memorials. The client, Bischof said, had been blind and unable to speak for years, and had spent most of his time in a chair. After his death, however, Ryan researched his life with the fervor of a biographer, and at the service, she managed to paint a surprisingly complex and charming portrait of him.

It turned out that years ago, before he went blind, he’d been impish and playful. One of his favorite tricks, the small crowd learned, was to remove the screws from people’s chairs, sending his victims tumbling to the ground.

“Clients feel a sense of belonging, and the staff feel more attached to the clients than they actually admit to themselves,” Bischof said. “When clients pass, she’s able to draw that feeling out. It gives a great crescendo to people’s lives.”

There are scores of people who, like the priest, like Bischof, cannot understand how Ryan has summoned the strength, day in, day out.

When one client struggled to participate in music class because he’d suffered neurological damage, she tied a string of shells around his foot, the one part of his body he could still move voluntarily.

Weeks ago, she learned that a patient named John was losing his ability to speak. She figured out that if she put her arm behind John’s back, just so, she could ease the pressure on his neck, allowing him to exhale deeply into a microphone during one recent church service. When he did, she turned to the congregation and lifted her hands toward the sky.

“Thanks be to God,” she said. “We take so much for granted.”

And that, Ryan said, is her little secret: She doesn’t view her work as selfless at all. Indeed, she credits her clients with saving her life.

Fionnuala Ryan was the fifth of six children born to a customs officer and a homemaker in County Monaghan, in northeast Ireland. She entered the convent in 1951, at 18, joining the Sisters of St. Louis.

The sisterhood has a strong foundation in education, and she was dispatched to the United States in 1958 to teach music, first at St. Joseph’s Elementary in Long Beach, then Mater Dei High in Santa Ana and Louisville High in Woodland Hills. The music programs -- the choirs, in particular -- became her passion, and her obsession. She was a skilled director, and her choirs were good. But she was driving herself into the ground, working crushing hours in a fruitless pursuit of perfection.

By 1980, she was depressed and burned out. A nervous breakdown followed. It was, in a sense, the greatest thing that could happen to her. She would become like Paul in 2 Corinthians, she said; her weakness would reveal her strength.

A friend suggested that Ryan try music therapy. She started working at Lanterman in 1985. It was a place, she sensed immediately, of healing.

For years, there had been no room for improvisation; now each minute was improvised. The pursuit of perfection that had nearly driven her mad -- of perfect pitch, perfect harmonies -- suddenly seemed a little silly.

“Oh, we miss so much,” Ryan said. “We get so busy, so caught in an agenda, and we forget even that heaven, or paradise, is really about presence. These clients are calling: Be present with me. Sit with me. Laugh with me.”

Tears streamed down the furrows in her face. She said they felt good and declined a tissue. “These people healed me,” she said. “They taught me how to play. They taught me what it means to be beautiful -- the beauty of the soul. We can all learn from them.”

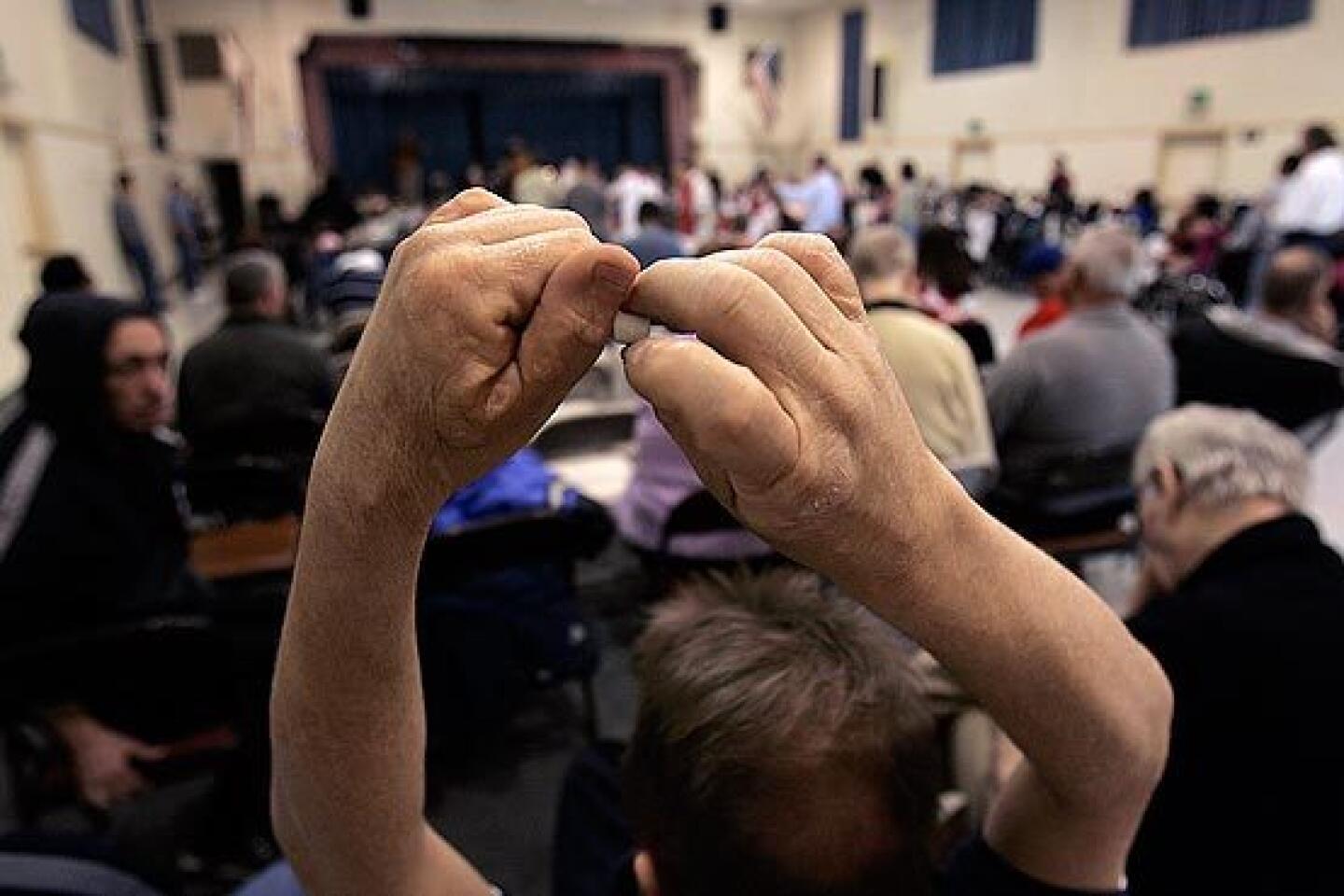

Back in the rec center, staff members had distributed copies of the Bible to Ryan’s flock, lifting the hands of many clients and placing them on top of the small books if the clients were unable to hold them.

“Welcome, Michael,” she said into the microphone. “Welcome, Steve. Good morning, Betty.” Then, to everyone: “Good morning!”

The student volunteers offered a feeble response suggesting that they were not pleased to be awake.

“There is no mumbling at Lanterman!” Ryan announced. “We are here with people who have no voice. We are their voice.”

She tried again, with more success.

She matched each student with a client.

“Be open,” she told them. “Bend down. Introduce yourself. Try to get eye contact.”

Soon, one student was holding a client’s hand, another stroking a client’s hair.

“I see beautiful things!” Ryan called out, then came alive, dancing through the aisle and waving her arms about. “Blow a kiss to Jesus!” she shouted.

“That’s right, blow a kiss! We get so afraid of being children again. It’s OK!”

The night before, she’d spent the evening reading poetry, a passion of hers. She’d become fixated on a poem called “Love After Love,” by one of her favorite writers, the Caribbean poet and playwright Derek Walcott.

It was about redemption, about remembering to be kind to yourself:

Give back your heart

To itself, to the stranger who has loved you

All your life, whom you ignored

For another, who knows you by heart. . . .

Sit. Feast on your life.

“That made sense to me,” Ryan said with a wink after the service. “I think I might try some of that.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.