The rise and fall of Lee Baca, L.A. County’s onetime ‘Teflon Sheriff’

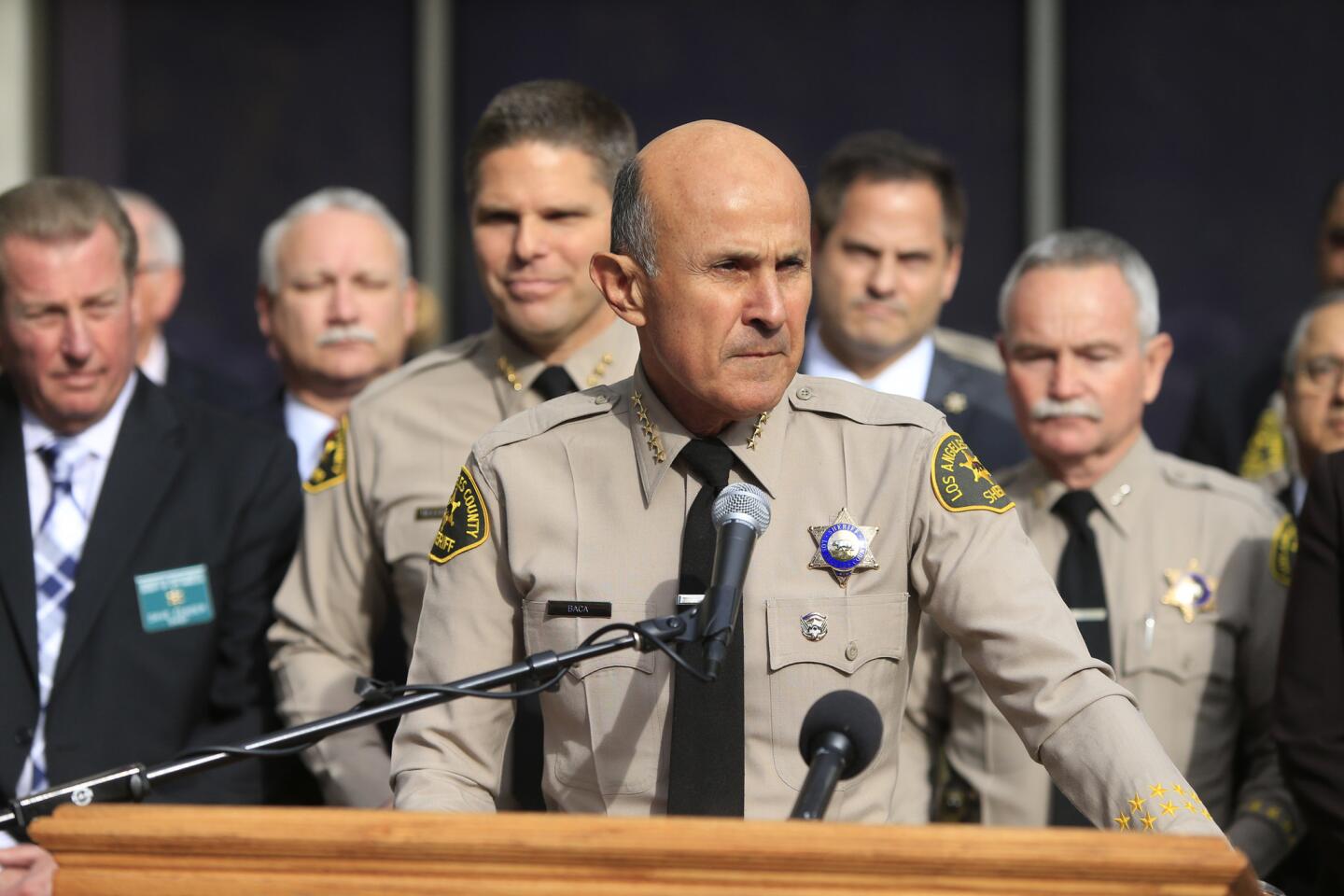

Former L.A. County Sheriff Lee Baca’s conviction Wednesday for obstructing a federal investigation into abuses in county jails and lying to cover up the interference is a dramatic end to career marked by both early promise and running scandal.

For years, Baca won praise in law enforcement circles around the nation for his outreach to Muslim groups, progressive views on educating jail inmates and battling homelessness. But in the years before he stepped down from office in 2014, his department had been mired in scandal.

Here is a look at Baca’s record from the pages of The Times:

An East L.A. native

Raised by his grandparents in working-class East Los Angeles, Baca dropped out of community college. He was hired as a beat cop with the Sheriff’s Department and worked his way up the ranks, earning a doctorate from USC. Along the way, he developed a philosophy about policing that went beyond simply arresting criminals and included rehabilitation and education.

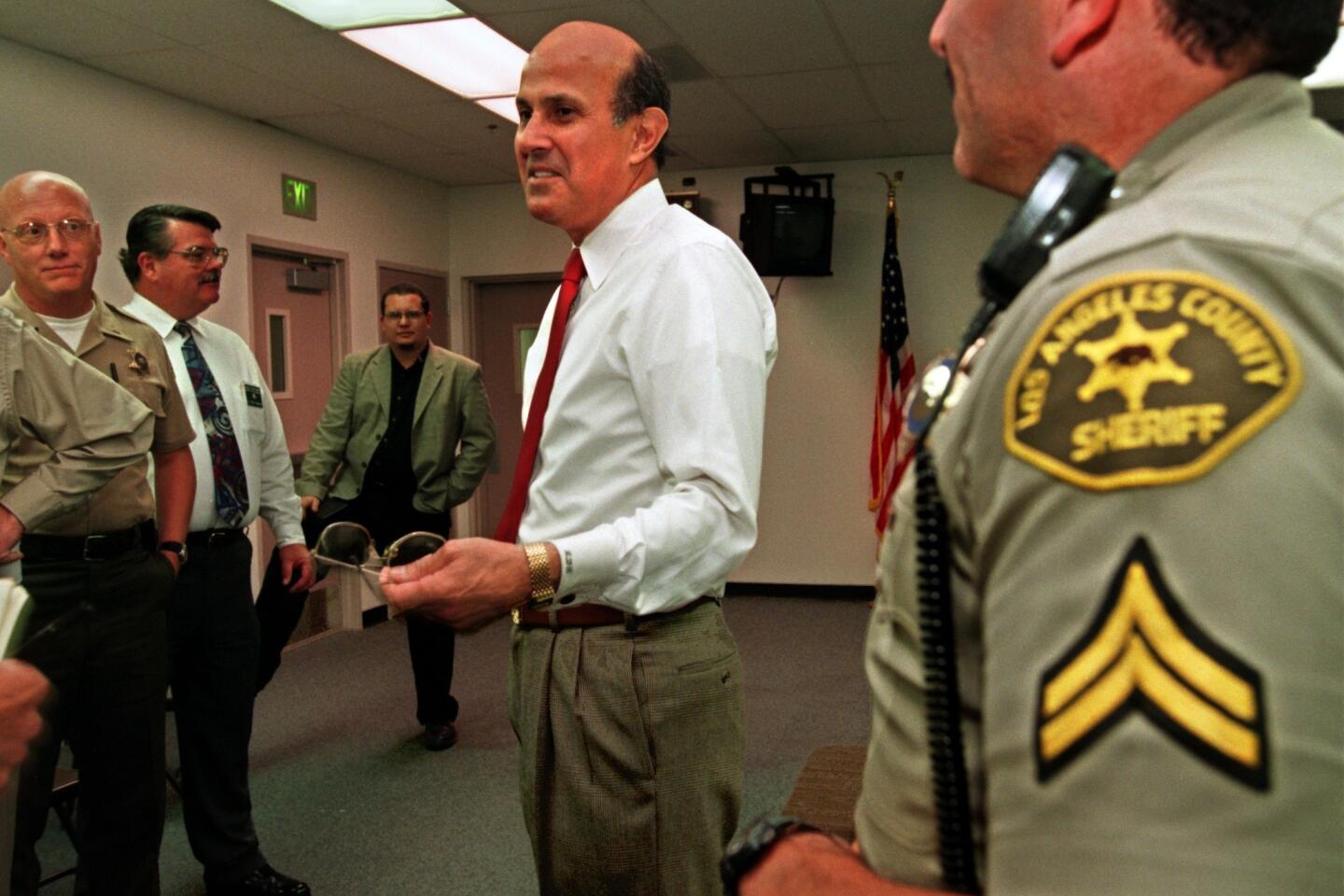

In 1998, as a top commander within the department, he launched a campaign to unseat his longtime mentor, incumbent Sheriff Sherman Block. One top aide recalled Baca’s approach then as being the opposite of Daryl Gates, the controversial former LAPD chief criticized for a militaristic take on law enforcement that alienated minority communities. Baca drew his support from ethnic communities within the county.

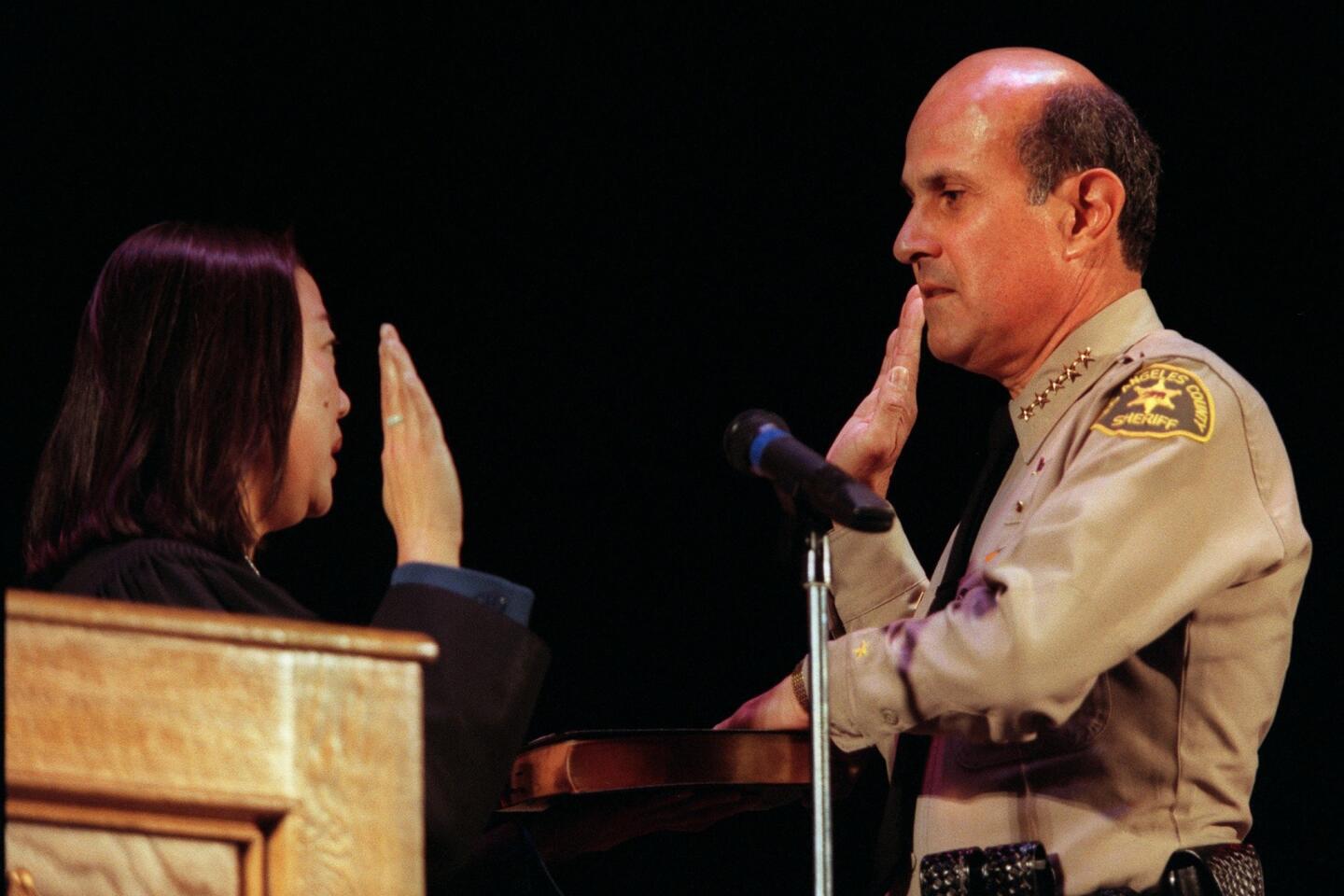

Hailed as reformer

In his first years in office, Baca impressed some reformers.

He required his deputies to memorize a pledge to fight against racism, sexism and homophobia. He created dozens of ethnic advisory committees, formalizing a pipeline between his office and the county’s many minority groups. He opened a drug and alcohol treatment center for jail inmates as part of rehabilitation efforts.

Baca successfully pushed for a watchdog agency that would monitor how the department handled allegations of misconduct by deputies. The move was all the more notable because it came at a time when the LAPD was mired in the Rampart corruption scandal.

A few years into his tenure, Baca was faced with a series of problems. Racially motivated violence erupted between black and Latino inmates. Sheriff’s officials were blamed for failing to prevent a string of inmate killings by other inmates.

The ‘Teflon Sheriff’

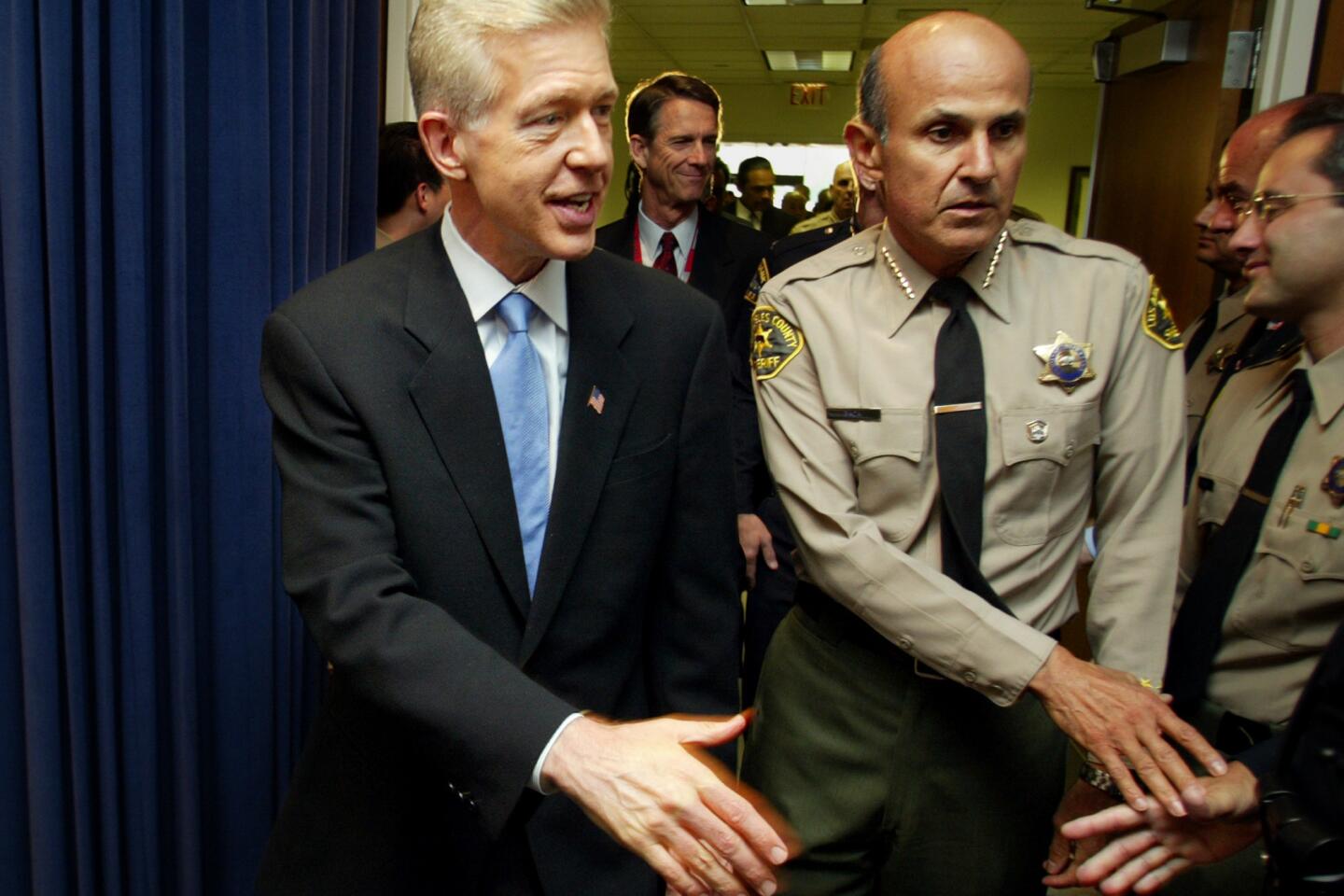

By the mid-2000s, Baca was under fire for releasing thousands of inmates early from his cash-strapped jails, with many of the freed going on to commit new crimes.

His department was accused of giving actor Mel Gibson preferential treatment following his 2006 drunk driving arrest in Malibu. A year later, Baca’s decision to free Paris Hilton weeks before she finished her jail term for a probation violation made international news.

The sheriff weathered the storms, comfortably winning reelection. L.A. Weekly began calling him the “Teflon Sheriff.”

Brought down by jail scandal

The beginning of the end of Baca’s career as sheriff came several years ago when federal authorities began investigating allegations of abuse in the jail system, which he oversaw.

The investigation led to numerous prosecutions and convictions of lower-level jail officials and sheriff’s commanders.

But the federal prosecutors focused on Baca’s role in trying to impede the investigation.

To get to Baca, prosecutors methodically worked their way up the ranks of a group of sheriff’s officials who were accused of conceiving and carrying out a scheme to impede the FBI jail inquiry. In all, 10 people — from low-level deputies to Baca and his former second in command — have been convicted or pleaded guilty. Several other deputies have been found guilty of civil rights violations for beatings they delivered on inmates and visitors in the jails.

Prosecutors argued that Baca was part of a conspiracy, hatched in the summer of 2011, to obstruct attempts by the FBI to investigate allegations of corruption and abuse by deputies in his jails.

Although Baca delegated day-to-day handling of the obstruction plot to his trusted undersheriff, Paul Tanaka, he helped direct it and was kept apprised of developments from his place at the top of the command chain, prosecutors led by Assistant U.S. Atty. Brandon Fox told jurors. The scheme, prosecutors argued, included efforts to keep FBI agents away from an inmate who had been working for them as an informant, manipulating potential witnesses in the federal inquiry and intimidating an FBI agent.

In his closing words to the jury before they began deliberating, Fox excoriated Baca, comparing him to a cowardly chess king who remained safely back while dispatching pawns and other underlings to do his “dirty work.”

Courtroom drama

The government’s first trial against Baca ended in a mistrial. So prosecutors adjusted their case this time around.

The addition of new witnesses, elimination of others, and playing excerpts of Baca’s interview were an attempt by prosecutors to address what jurors from the first trial said was a fundamental problem with the government’s case: A lack of hard evidence tying Baca directly to the plot to interfere with the FBI investigation.

In the face of the government’s adjustments, Baca’s attorney, Nathan Hochman, stuck largely to the script that almost won Baca his freedom in the first trial. He argued that Tanaka took advantage of the sheriff’s trust, keeping Baca in the dark while he carried out the obstruction scheme. And as before, Hochman tried to poke holes in the government’s case by emphasizing the lack of any smoking gun that proves Baca’s guilt.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.