Q&A: The prosecutor who took down Lee Baca calls it a day

When Brandon Fox moved to Los Angeles five years ago from Chicago to join the U.S. attorney’s office, the office had launched an investigation into abuses and corruption by sheriff's deputies working in county jails. Prosecutors were focused on building cases against a handful of deputies for beating inmates, but Fox suspected something larger was at play: a conspiracy by sheriff’s officials to obstruct the federal probe.

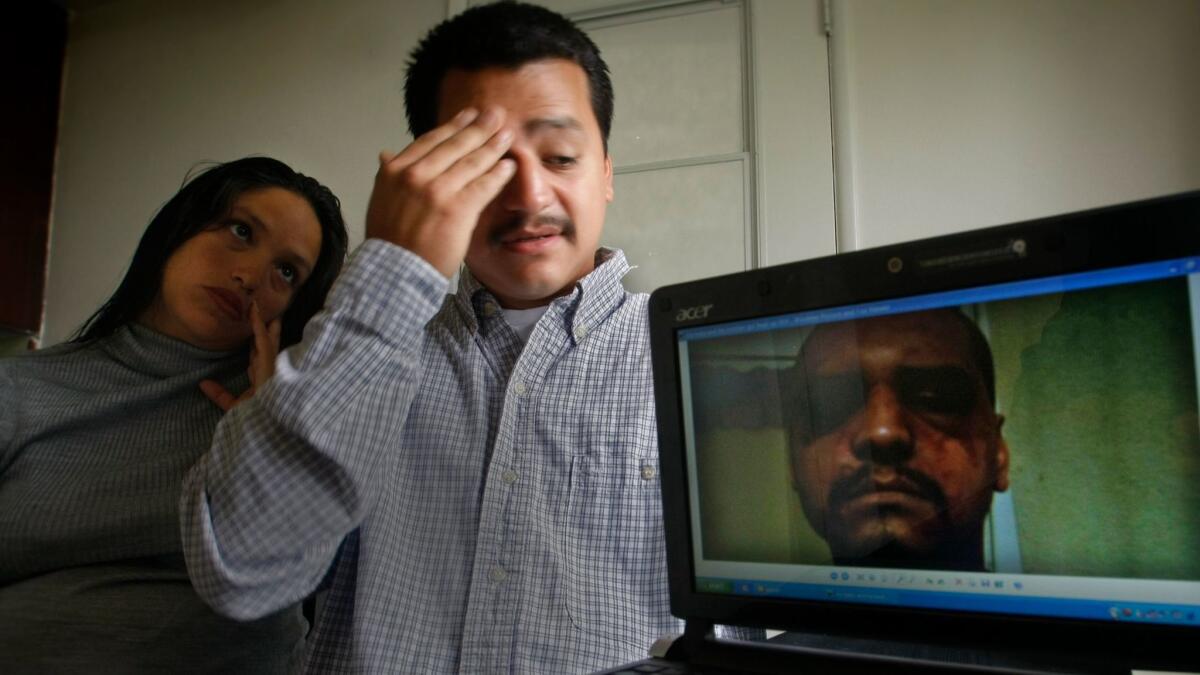

On Friday, Fox stood in a downtown courtroom as former L.A. County Sheriff

Baca’s sentencing marked the end of the line for Fox, who left the U.S. attorney’s office the same day to join a private firm.

What was happening with the sheriff’s investigation when you arrived in 2012?

There were a lot of abuse incidents that were being looked into. It was shortly after I started I think that our first big break came in the obstruction when [former Sheriff’s Deputy] James Sexton and someone else came to us and said, “There is something bigger going on than you realize.”

What was it like joining the team as an outsider?

I think it ultimately helped us [see that there was an obstruction of justice case to be made.] When I came in and said, “This is egregious conduct,” I think people in the office listened to someone who didn’t know the players and the personalities. The more I said it, I think the more they believed it.

How did the scope of the investigation take shape?

For the beatings cases, we decided early on that we needed to focus on just a handful of them. We couldn’t handle more than that because of manpower issues. So, we decided on the three or four that we believed we could prove if the evidence fell where we thought it would fall.

We thought that between the handful of abuse cases and the obstruction case we could make a big impact. In federal prosecutions, a lot of the calculation is, “How do we get the best bang for our buck in terms of impact?” Charging 100 cases and being able to prove 50 of them was going to give us almost the same impact as charging three or four cases on the beating side and being able to prove every single one of them. We’d have made our point — the Sheriff’s Department was going to know it needed to change.

In federal prosecutions, a lot of the calculation is, ‘How do we get the best bang for our buck in terms of impact?’

— Brandon Fox

That’s interesting. I think many people, myself included, assumed there were many more deputies who would have been prosecuted for abuses had your team not changed course to focus on the obstruction case.

The abuse cases are all incredibly hard to prosecute. You’re dealing with inmates that often have mental health issues, bad criminal histories, violence. We decided we need to make our cases by having a witness in addition to the inmate. There weren’t that many other than the ones we brought.

How did the obstruction case come into focus?

[Note: The obstruction scheme carried out by sheriff’s officials included intimidating an FBI agent, pressuring deputies not to cooperate and an effort to keep FBI agents away from an inmate who had been working for them as an informant.]

I thought it was going to be very difficult to prove each part of the case on its own. For example, if we brought a case just about hiding the informant from agents, it would have been hard to prove they were trying to obstruct the investigation and not simply moving him around for his own protection, as they claimed. But when we learned they were tampering with witnesses, that did something important for us: We had the same players all of a sudden involved in the different pieces of the conspiracy. Some of the people involved in the witness tampering were involved with hiding the informant and were also involved with intimidating the agent. So now we’ve got a larger organized piece that we didn’t have before. That’s really when we first saw this as one big conspiracy.

Then it was a question of how high up did this go? Who knew about this?

Then it was a question of how high up did this go? Who knew about this?

— Brandon Fox

You must have suspected it went high into the department’s senior ranks.

Suspicions versus what we could prove – two different things. If the case was going to go higher than [the seven lower-ranking deputies and supervisors originally indicted], we needed someone to give us some evidence. But no one who had communicated with [former Capt. Tom] Carey, [former Undersheriff

Were there sleepless nights when you ultimately decided to go after Tanaka and Baca?

I’ve always believed you can’t prosecute cases while being afraid. You can’t be a lawyer if you’re afraid of the consequences of being wrong.

In public corruption cases, sometimes you have to go after people the public believes are good people. And sometimes they are good people, but they have committed crimes and need to be prosecuted. We’re apolitical, which I love. We can go in and do things because we think they’re the right thing to do without worrying about who is involved.

Baca’s first trial ended in a mistrial when the jury deadlocked with only one juror voting to convict. Did you consider not retrying him?

No. I knew I wanted to retry the case. I knew we could do better. I didn’t think the evidence supported giving Baca a walk.

More than a few of the defense attorneys you’ve gone up against have criticized you for your ‘win’ at all costs’ approach.

Anyone who knows me knows that’s not true. I believe in justice. These are very difficult cases that are emotional for each side, and I think it is just a reaction people have. They lost.

Any big regrets, things you wish you could do over?

I’m sure there were many mistakes along the way. But, overall, I am very proud of the work we did. I think justice was absolutely done in this case.

After spending so much time thinking about him, what is your view of Baca?

He’s a very complex individual. He is the most difficult person I have ever had to be a part of sentencing for. He’s such a mixed bag of good and bad. Is Baca a good person or a bad one? You probably have people on the street who will say different things. But he committed a crime so we had to prosecute him. It’s our job. If we don’t do it, no one will.

Follow @joelrubin on Twitter

ALSO

Former Sheriff Lee Baca defiant to the end, even after prison sentence

Two sheriffs elected as reformers end up destroyed by corruption scandals

Ex-L.A. County Sheriff Lee Baca sentenced to three years in prison in jail corruption scandal

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.