There’s a real-life Michael Connelly character in the LAPD, and she’s gunning for Harry Bosch’s job

Author Michael Connelly recently introduced a new character, Renee Ballard, into the world of his Harry Bosch novels. Ballard is based on Los Angeles Police Department Det. Mitzi Roberts.

Mitzi Roberts always wanted to talk to serial killers.

A Los Angeles bartender and diner manager, Roberts was used to seeing cops stagger into her establishments, seeking a bite or a beer after their shift. Conversation between the investigators and Roberts, a self-described true-crime “fanatic,” came easily.

She told them of her desire to chase predators. At some point, one of them suggested a career change.

The move from diner manager to detective set Roberts on a career path that saw her climb the ranks of the Los Angeles Police Department — from a graveyard shift that is sometimes home to cops who have “screwed up” to a treasured spot in the elite Robbery-Homicide Division. After years spent fighting an uphill battle as a woman traversing a department long regarded as a boys’ club, Roberts found herself zipping around the southeastern United States on a collision course with one of America’s most prolific killers.

The veteran detective’s career history may read like it borrows a bit from the jacket copy of a popular crime novel, but it’s actually the other way around. In her 24-year career, Roberts has not only found herself involved in some of L.A.’s most infamous cases, but she’s also served as a muse to the city’s modern master of detective fiction.

In recent years, Roberts became the inspiration for Renee Ballard, the newest protagonist to grace the pages of Michael Connelly’s bestselling novels. Ballard — a Hollywood Division detective exiled from Robbery-Homicide who shares Roberts’ real-life love of surfing, knack for swift verbal jabs and dogged dedication to the job — is more than just a passing interest for Connelly. According to the author, Ballard could one day replace Harry Bosch, the beleaguered LAPD detective who appears in 22 of his novels.

‘You have that thing. Maybe one in one hundred have it. You’ve got scars on your face but nobody can see them. That’s because you’re fierce. You keep pushing.’

— Det. Harry Bosch, describing Renee Ballard, in “Dark Sacred Night”

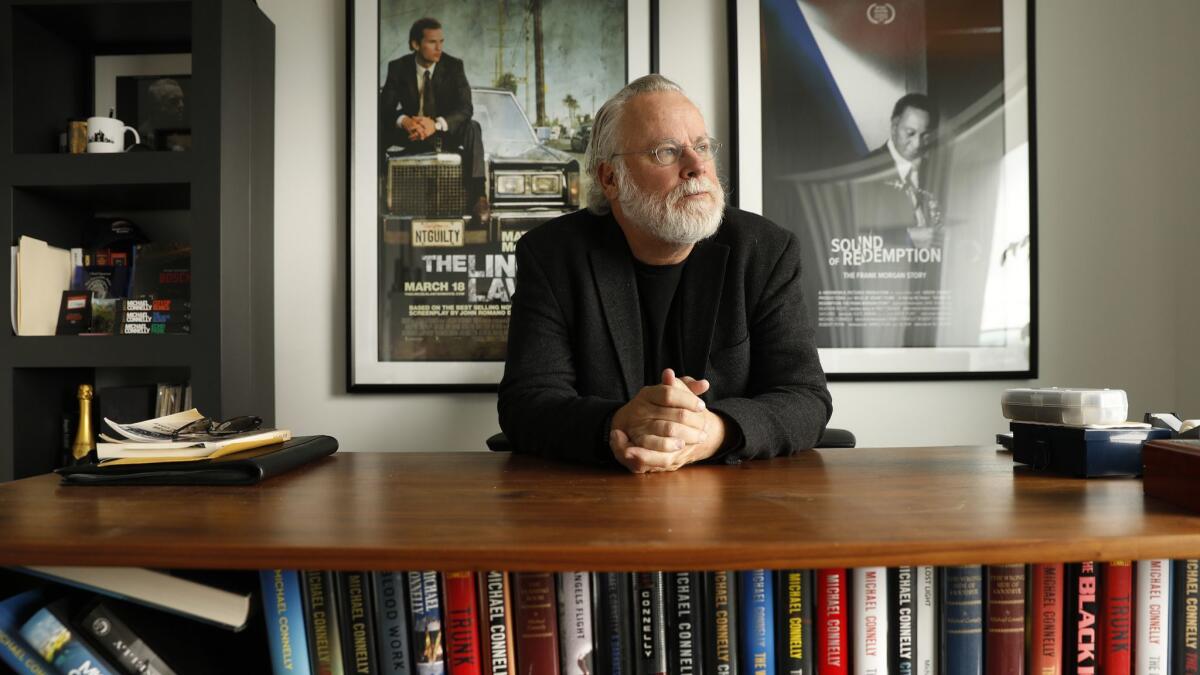

“I write in real time. My characters age, and Bosch is aging out,” Connelly says. “Hopefully, I’m gonna be writing longer than Bosch is gonna be detecting, so it was kind of like looking for a new protagonist to carry on.”

Connelly says most of his protagonists — including Bosch, reporter Jack McEvoy and Mickey Haller of “Lincoln Lawyer” fame — are amalgams of individuals in his personal and professional lives. But Ballard is the first to emerge from a single source of inspiration.

“It was all there. I didn’t have to look for anything else,” he says of his decision to base Ballard on Roberts. “She was completely open with me and willing to work with me … it’s almost as if you went to one of your best friends and you said, ‘Help me out,’ and they said, ‘Of course.’”

Spend a few minutes with Roberts and it’s easy to see how she might fit neatly inside the pages of a crime novel. She’s quick with an insult, but quicker with a smile, able to put someone at ease or on the back foot almost at will.

On the set of the Amazon series “Bosch” last year, Roberts went from wrestling a Sam Browne belt into place on an actor’s waist to squirming as one of her old LAPD mentors snuck up from behind and whispered in her ear. He was trying to embarrass her with a story about a night of drinking gone sideways while working a case years ago, but Roberts had the older man — another Connelly advisor and former LAPD cold-case investigator named Rick Jackson — blushing and backing away when she reminded him that he’d lost the battle with the pitcher of margaritas in question long before she did.

“I’ve always been the type that can sort of move on and adapt to the personality that I’m dealing with,” Roberts said of climbing in a department where the ribbing from male officers could quickly veer from playful in nature to blatant misconduct.

When describing Ballard on the page, Connelly makes no secret of his source material. When he first crosses paths with Ballard in “Dark Sacred Night,” the 2018 novel that marks the first meeting between Connelly’s two fictional LAPD investigators, even Bosch sizes up a figure reminiscent of Roberts.

“She was attractive, maybe mid-thirties, with brown, sun-streaked hair cut at the shoulders and a slim, athletic build,” Connelly wrote. “She was wearing off-duty clothes. The night before, she had been in work clothes that made her seem formidable — a must in the LAPD, where Bosch knew female detectives were often treated like office secretaries.”

Roberts’ and Ballard’s dual ascents come at a time when representation of women in popular culture has been a focal point for authors and screenwriters. Female protagonists have been championed in the burgeoning superhero universe with films like “Wonder Woman” and “Captain Marvel,” but the crime fiction community has at times struggled with issues of inclusion. Although the genre’s stigma as a haven for brooding, chain-smoking detectives and damsels in distress is long outdated, its most famous characters are still often white men.

Female protagonists like Lisbeth Salander, Kay Scarpetta and Tess Monaghan have become increasingly popular in suspense and thriller genres, but experts say it’s still significant for someone of Connelly’s stature to choose to write from a woman’s perspective.

“The more that people are represented in books, in fiction, in genre fiction, the more it kind of opens things up for other people to then write their own works … it just opens things up to people that they never thought possible,” said Sarah Weinman, author of “The Real Lolita,” who has also compiled an anthology of crime fiction written by women in the 1940s and ’50s. “When you read your own experiences, it feels like that’s speaking to you instead of seeing another white male, and having to have that stand in for your experience.”

Ballard debuted in Connelly’s 2017 novel, “The Late Show,” and co-starred alongside Bosch in “Dark Sacred Night” last year, working to save the veteran detective from separate physical and moral reckonings over the course of the novel. The two will team up again in “The Night Fire” later this year.

An animal lover who never strays far from the beach when off duty, Ballard is often found sleeping in a tent in Venice with her faithful dog, Lola, then paddle-boarding out into the surf before she returns to work. Roberts, an ex-surfer who still does her fair share of kayaking, camps at the beach often, but she doesn’t lay her head to rest on the sand as frequently as her fictional counterpart.

The owner of two quarter horses and three Dobermans — “they are all my Lolas,” she says — Roberts also volunteers for a rescue group, where she agreed to foster a three-legged dog that had been seriously injured in a car accident. The head veterinarian agreed to greatly reduce the cost of the dog’s medical bills, on the condition that Roberts name the pup Bosch.

When readers first meet Ballard in “The Late Show,” the veteran detective is marooned on an overnight shift in Hollywood after she accuses a supervisor of forcing himself on her. Ballard’s origin story is eerily reminiscent of recent scandals in the LAPD — where a number of female officers and investigators have spoken out about or sued over sexual misconduct allegations — but it also calls to mind some of the sexism Roberts says she faced as a young detective.

“I’m not gonna sugarcoat it. It’s there. It was definitely more at the beginning of my career. Things have gotten much better in the department and we’re evolving, though there are still issues,” she said. “I’ve seen some really, really bad mistreatment of females other than myself, where I really support them taking it a step further because it’s blatant, and it’s just wrong.”

‘I’m not gonna sugarcoat it. It’s there.... I’ve seen some really, really bad mistreatment of females.’

— Det. Mitzi Roberts, on sexism in the LAPD

Early in her career, Roberts investigated gang crime in the San Fernando Valley, before she was reassigned to an overnight shift in the Rampart Division — the experience that Connelly would later pull from as he created “The Late Show.”

After five years on the job, Roberts passed the detective’s exam and transferred into Robbery-Homicide in 2000 — becoming one of the first women assigned to the elite unit, she said. At the time, Roberts said, the department was far from a model of inclusiveness. She still remembers being blown away by a lieutenant’s remark during a conversation about other women joining the unit.

“Well, she ain’t coming on my squad. I have my female,” the lieutenant said.

Despite the misogyny, Roberts won over her colleagues in Robbery-Homicide with her sense of humor and tenacity in the field.

But while Roberts chooses not to dwell on the uglier parts of her career, her current partner, Det. Tim Marcia, remembers watching her swim through a pool of crass comments on more than one occasion.

“You had old crusty homicide detectives, and Mitzi would walk in and she would get the catcalls and the ‘Hey, baby, come over here,’ ” he said. “Maybe it was because she was a bartender before she came on, but she just knows how to work that. Make the guys feel very important and keep it moving.”

Partnering with Marcia not only helped ingratiate Roberts in Robbery-Homicide; it also connected her with the man who would create her fictional alter-ego. Connelly relies on a few LAPD officers to check the authenticity of his work, and Marcia was among those trusted few. Soon, Roberts started getting invites to join him for breakfast meetings with Connelly at the Pacific Dining Car in Westlake.

Fascinated by Roberts’ tales from the night shift and the way she talked about her desire to advance in the department, Connelly says the Ballard character soon started to take shape in his head.

“Cops don’t know the gold they have. They think that you want to know about procedure, and I really don’t. I can get that almost anywhere,” Connelly says. “It’s more like, I want to learn about the life and why you do it and how you do it and how you keep yourself mentally healthy while doing it.”

Roberts said she was a fan of Connelly’s work prior to meeting him — he has since vaulted over Stephen King and become her favorite author — but she didn’t actually know he’d created a character in her likeness until Connelly discussed “The Late Show” on a podcast in early 2017.

Like any classic Connelly character, Roberts also made herself an enemy of a serial killer in recent years.

While working cold cases in 2012, she was put on the trail of a vicious predator who was suspected in the strangulation killings of several women across the southern U.S. The former boxer had repeatedly attacked prostitutes, drug addicts and other vulnerable women in 19 states over the course of 35 years, but despite being arrested in Florida and Mississippi during his decades-long rampage, no one had been able to keep him locked up. An arrest in San Diego on attempted murder charges somehow resulted in only a short prison sentence for assault in the early 1980s, and it wasn’t long before the man had killed several women in Los Angeles.

With the benefit of DNA evidence, however, the LAPD was able to attach a name to the suspect — Sam Little.

“He had such a hatred for women, and he was just like preying on the weakest women, what society would consider throwaway women: prostitutes, black women in the South in the ’80s,” Roberts said.

Roberts had a warrant for Little’s arrest but almost no idea where he was. Little was elusive, choosing to either live out of a car or roam between shelters in different states. From her office in L.A., where interest in catching Little was starting to wane among some of her supervisors, Roberts continued to track his movements through the Midwest and Southeast.

“We were always two days behind him,” she said.

A few months later, Roberts’ ability to make fast friends paid off. An investigator in Kentucky told her he believed Little was using a prepaid benefits card. Roberts called the card company’s hotline and was able to use some of Little’s identifying information to get a list of his recent transactions. His last five purchases had all been at the same store, a block or two away from a shelter.

The U.S. Marshals Service had Little in handcuffs within two hours. He was later convicted of killing three women in Los Angeles in the 1980s, and last year Little confessed to the murders of at least 93 women across the U.S., a bloody spree that spanned four decades. At least 20 of those slayings took place in Los Angeles, and Roberts has been tasked with helping bring those cases to a close.

Connelly admits that it was mere coincidence that his first Ballard novel was published the same year that the #MeToo movement exploded. He hadn’t set out to create a female detective. But after spending time with Roberts, Connelly realized he was in the privileged position of getting to speak with one of his own characters face to face.

“How many writers of crime fiction are out there who wish they could have breakfast every Thursday with a real-life homicide detective, no matter what the gender is?” he asked. “I have amazing access, and she’s a big part of it, so I’d be a fool not to kind of try to harness that into something that I’m writing.”

Although he remains tight-lipped about the future of Bosch, it appears Ballard is here to stay, and he hopes the Roberts-inspired investigator might make his writing more accessible to readers. Especially one in his own home.

“I probably shouldn’t admit this, but I have a 21-year-old daughter who doesn’t read my books, and I think it’s because they’re about this loner male, so how does she relate?” he said. “I did think while I’m writing this that maybe I’m starting a series that my daughter could get into.”

While Roberts says she’s honored to serve as the muse for Ballard, her day-in, day-out ethos as a detective is a little more in line with a phrase made famous by Bosch. Whether she’s tracking a notorious serial killer or probing a case few will ever hear about, she looks at each victim the same.

“Everyone counts,” she said. “Or nobody counts.”

L.A. Times Today airs Monday through Friday at 7 p.m. and 10 p.m. on Spectrum News 1.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.