Biggest earthquake in years rattles Southern California

A 6.4 magnitude earthquake rattled Southern California on Thursday, the largest temblor to hit the region in nearly two decades.

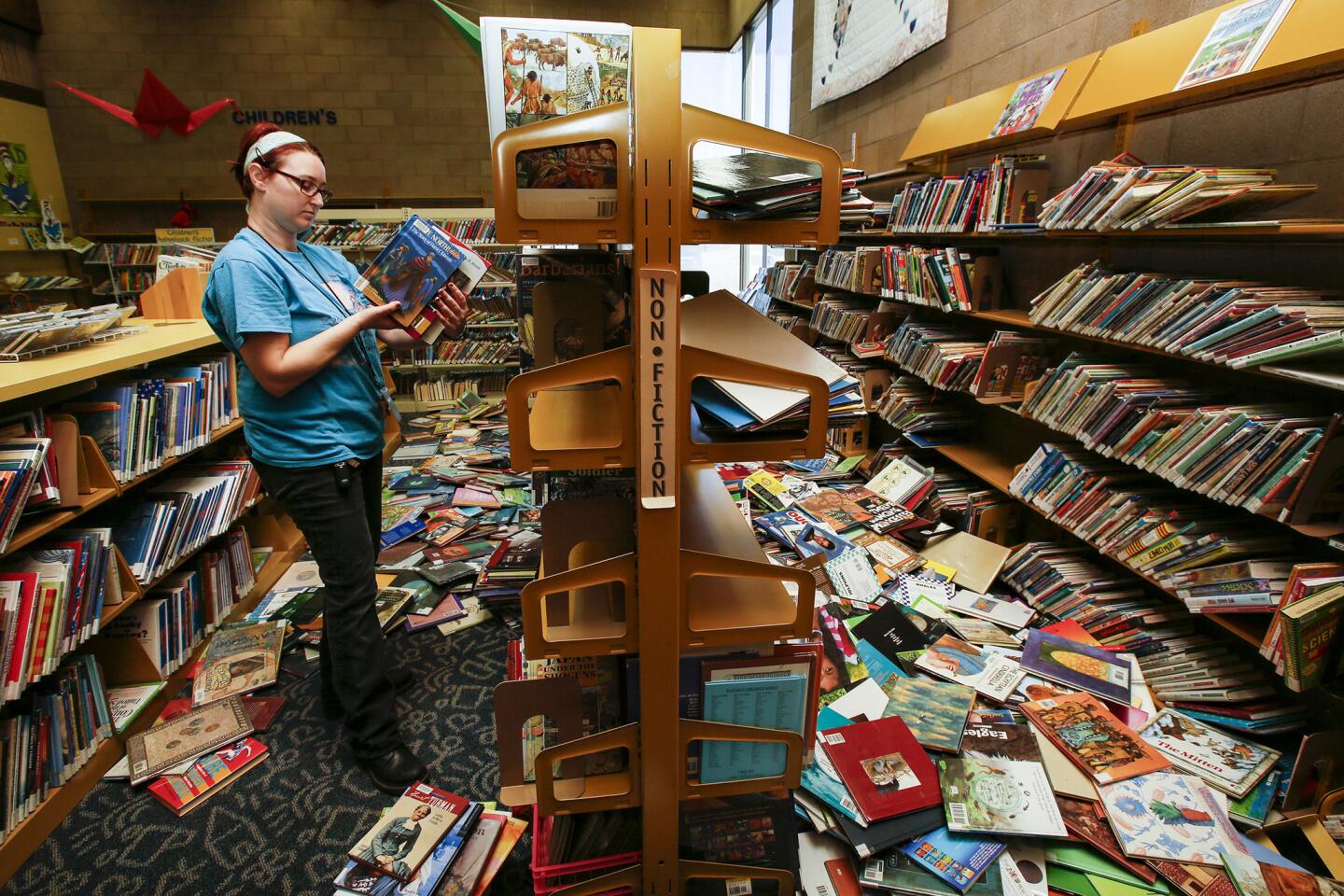

Reporting from Ridgecrest, Calif. — The largest earthquake in two decades rattled Southern California on Thursday morning, shaking communities from Las Vegas to Long Beach and ending a quiet period in the state’s seismic history.

Striking at 10:33 a.m., the magnitude 6.4 temblor was centered about 125 miles northeast of Los Angeles in the remote Searles Valley area near where Inyo, San Bernardino and Kern counties meet. It was felt as far away as Ensenada and Mexicali in Mexico, Las Vegas, Phoenix, Reno and Chico, Calif. A 5.4 magnitude aftershock awoke many Friday morning.

For the record:

1:00 p.m. July 4, 2019An earlier version of this article said the Ridgecrest earthquake was the largest since the 1994 Northridge quake. Thursday’s 6.4 quake was weaker than the Northridge quake, which was magnitude 6.7, not 6.6 as a previous correction indicated.

Authorities said there were no immediate reports of deaths, serious injuries or major infrastructure damage, though emergency responders were still inspecting areas around the city of Ridgecrest.

Patients at Ridgecrest Regional Hospital were evacuated “out of an abundance of caution,” hospital Chief Executive James Suver said. About 20 patients were transferred to other facilities while seismic engineers inspected broken pipes in the facility. “For true emergencies, we will stabilize them and then get them to the right level of care,” he said.

Ridgecrest, a community of about 29,000 known to many skiers as a pit stop on the way to Mammoth, was inundated with offers of help, from neighboring towns, congressional leaders such as Rep. Kevin McCarthy and Sen. Kamala Harris and even the White House, Mayor Peggy Breeden said.

FULL COVERAGE: 6.4 July 4 Southern California earthquake »

”With all this cooperation … we expect we will be able to move on to this and not see too many awful things happen,” Breeden said.

The quake, estimated to have been felt by some 15 million people, was the largest with an epicenter in Southern California since the magnitude 7.1 Hector Mine quake struck the Mojave Desert in 1999, about 35 miles north of Twentynine Palms Marine Corps base. The last earthquake felt as widely as Thursday’s was the magnitude 7.2 earthquake on Easter Sunday 2010 that had an epicenter across the border in Baja California.

Before Thursday, it had been almost five years since the state experienced an earthquake of magnitude 6 or stronger. Experts had said the period of calm was sure to end, and when it did it would likely bring destruction.

The sparsely populated location of the Searles Valley quake appeared to mitigate the damage. A similar temblor, such as 1994’s magnitude 6.7 Northridge quake, in the Los Angeles basin would have undoubtedly meant deaths and severe property damage.

The rocking in Searles Valley began with two foreshocks: an initial quake of magnitude 4 at 10:02 a.m. Seven minutes later, a 2.5 temblor struck. About 24 minutes later, the mainshock began seven miles underground, lasting five seconds.

A swarm of 1,000 earthquakes hit Southern California — how nervous should we be? »

The quake hit as children were putting on a Fourth of July performance at Burroughs High School in Ridgecrest, Vicki Siegel said.

“The kids were crying and scared. And so I don’t know what kind of damage was done inside the building but we all got out,” she said. “They probably all have PTSD now.”

In rural Inyokern, about 10 miles from Ridgecrest, 72-year-old Virginia Henry was reading in her bedroom when it began. She lost power in her home, but was able to drive to Ridgecrest to check on her toy and game store.

“Everything is fine. A lot of businesses are open,” Henry said.

In L.A., the shaking felt longer, with a rolling quality that lasted long enough for many to pull out cellphones and document swinging chandeliers and sloshing swimming pools. One scientist in Pasadena estimated she felt 10 seconds of shaking, others thought it was longer.

Could your building collapse in a major earthquake? Look up your address on these databases »

Cynthia Alvarez, who was at work at a hotel in El Segundo when the quake happened, said the swaying made her dizzy.

“It wouldn’t stop. It just kept feeling like you were in a boat,” Alvarez said.

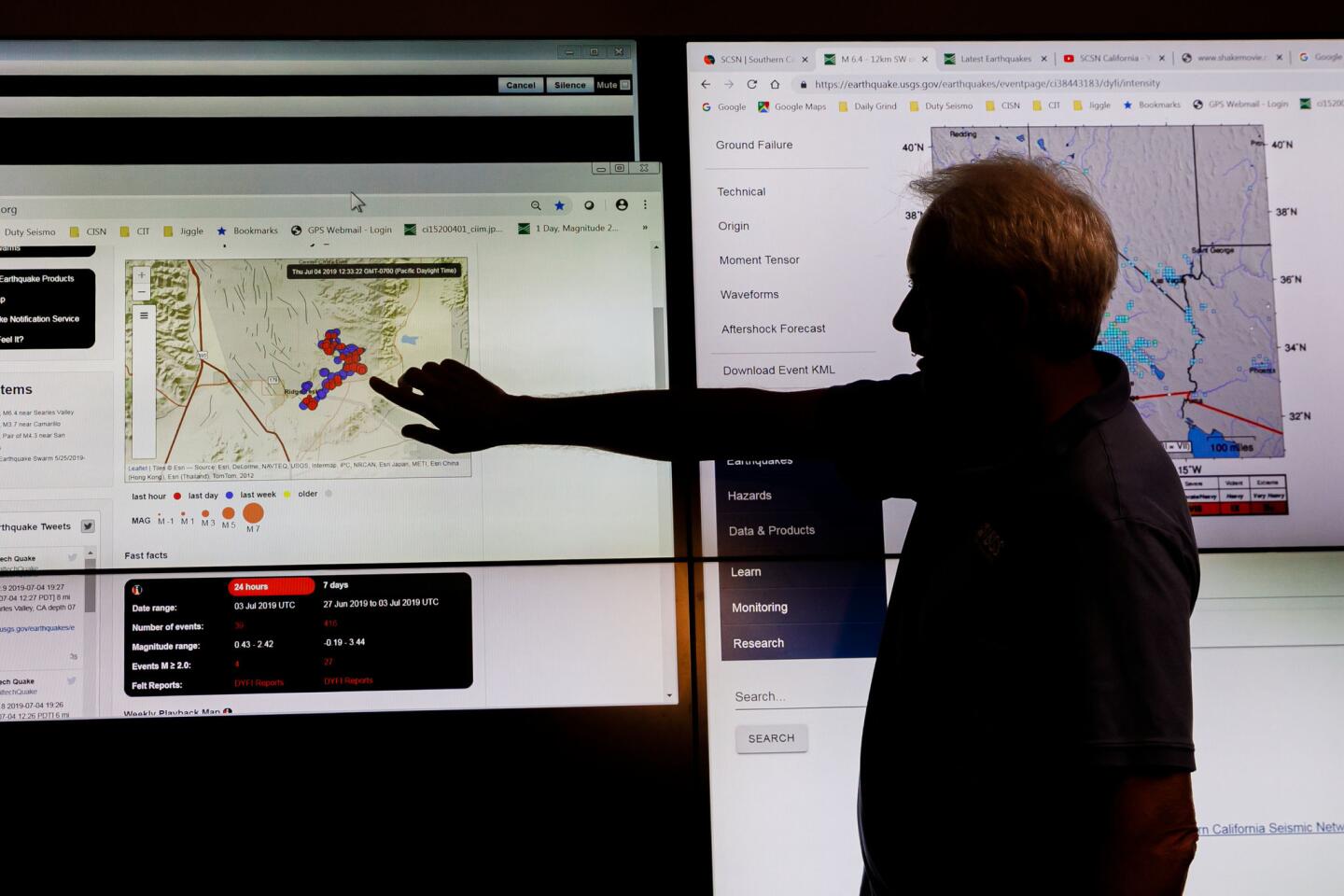

By midafternoon, more than 200 aftershocks had been recorded, including 10 of magnitude 4 or greater.

Caltech seismologist Lucy Jones, California’s foremost earthquake expert, said that aftershocks will continue to rumble through Kern County, and there is a small chance that the quake was a “foreshock” of an even greater temblor to come.

The Searles Valley temblor, like almost all earthquakes, was a product of randomness that comes with California straddling a major tectonic boundary, with part of the state sliding past the other.

California’s location on the border between the North American and Pacific plates is a central reason for what has made the state attractive in its recorded history — from its reserves of oil to its magnificent mountains — but also comes with the fraught reality of temblors that can come at any time, without any predictive pattern.

Get ready for a major quake. What to do before — and during — a big one »

“This is an area that normally has lots and lots of earthquakes,” Jones said.

Responding to reporters at a news conference asking if there might be any explanation for the earthquake — perhaps anything related to nearby geothermal energy production, which has been going on for many decades — Jones said there wasn’t any reason to believe that it wasn’t anything but nature doing its job.

“We are afraid of randomness and we try to make patterns,” Jones said, but “fundamentally, it’s a random distribution.”

“Having a 6.4 in this part of Southern California is totally typical,” said U.S. Geological Survey research geophysicist Rob Graves.

The faults that moved Thursday were nowhere near California’s most feared fault — they are about 100 miles northeast of the San Andreas, said Caltech seismologist Egill Hauksson.

Although the area east of the state’s grandest mountain range, the Sierra Nevada, is far from the San Andreas, it is a seismically active area. In 1872, an earthquake with an estimated magnitude of 7.2 hit the Owens Valley, which killed 27 people in Lone Pine. Mammoth has recorded dozens of magnitude 6 earthquakes.

Expect more earthquakes, possibly even stronger ones, seismologists say »

The Little Lake fault is in the general area of faults where Thursday’s earthquake occurred. It went through a magnitude 6 earthquake in 1984, Hauksson said.

Although Thursday’s earthquake was the first of magnitude 6 or greater since the Napa earthquake of 2014 killed two, injured 300 and damaged more than 2,000 structures, it was too early to say that California’s so-called earthquake drought was over.

“It takes a year or so of data to decide if the rate has changed. It’s like trying to say the stock exchange has gone up because it went up for one day,” Hauksson said.

Thursday’s quake also had nothing to do with the recent swarm in Fontana. It’s too far away, Hauksson said.

How to talk to kids about fires and earthquakes, before and after they happen »

The U.S. Geological Survey is dispatching geologists to Kern County to look for a surface rupture and gather other data.

The earthquake was centered roughly 80 miles northeast of a stretch of the 106-year-old Los Angeles Aqueduct spanning the San Andreas fault.

“Aqueduct personnel have been deployed as part of our standard earthquake response protocols to inspect the aqueduct and reservoirs,” said Joe Ramallo, a spokesman for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. “In the city, critical facilities are also being checked.

“There is no information nor reports of damage at this time,” he said.

How you protect yourself when an earthquake hits might be all wrong »

Ivan Amerson, 35, was eating lunch with his family in the isolated town of Trona when the quake hit.

“It was kind of an odd earthquake because you could hear it coming,” he said.

Afterward, the town became a chaotic scene, Amerson said. There was no power, a chemical plant that operates in town shut its doors abruptly and citizens, including Amerson, began packing up to leave.

Feeling earthquake anxiety? Here’s what you can do to be prepared »

He said he was headed to his father’s house in Costa Mesa.

“We’re going to the beach,” he said. “It’s a good time not to be inland.”

Times staff writers Joseph Serna, Irfan Khan, Anita Chabria, Alex Wigglesworth, Louis Sahagun, Alexa Diaz, David Montero, Mary Bernard, Alejandra Reyes-Velarde, Dakota Smith, Marques Harper, Phil Willon, Julia Wick, Robin Rauzi, Julissa James, Seema Mehta, Giulia McDonnell Nieto del Rio, Jeanette Marantos and Emily Baumgaertner contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.