In shadow of San Andreas fault, hundreds of Inland Empire buildings face collapse in huge earthquake

California learned the dangers of brick construction when a major earthquake struck Long Beach in 1933.

In a fast-growing Inland Empire churning out new housing tracts, the city of Redlands is a throwback to an older, more regal era.

The college town is graced by historic mansions, old orange groves and a vintage downtown that stands in deep contrast to the region’s big-box shopping centers and drive-through eateries. The town center is defined by century-old buildings filled with children’s boutiques, bakeries and cafes serving gourmet waffle sandwiches out of brick-lined alleys.

But danger lurks amid the idyllic charm of these brick buildings: As many as 74 in the city are not retrofitted to withstand a major earthquake, putting the public at risk should the bricks start to topple onto sidewalks, cars and pedestrians.

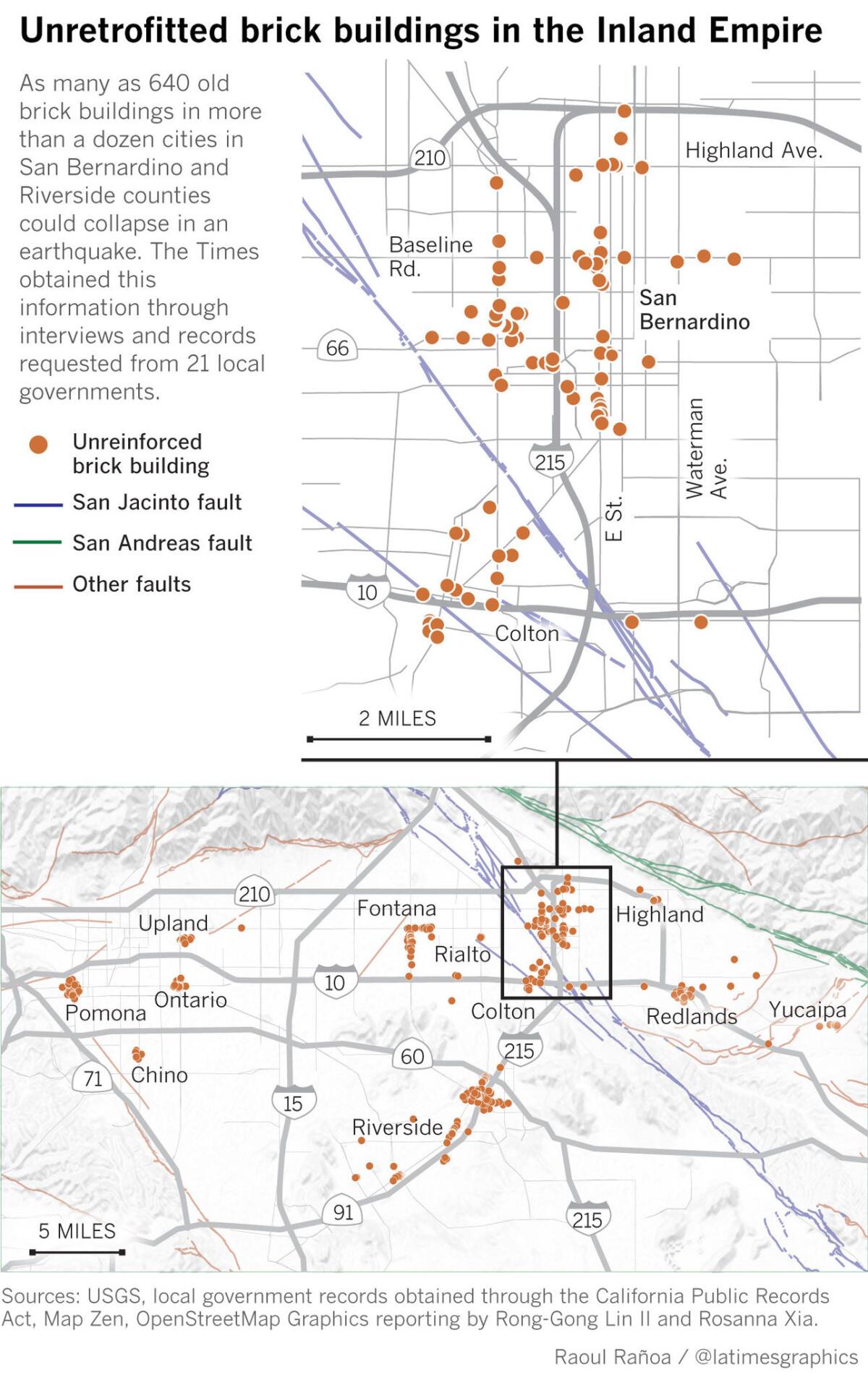

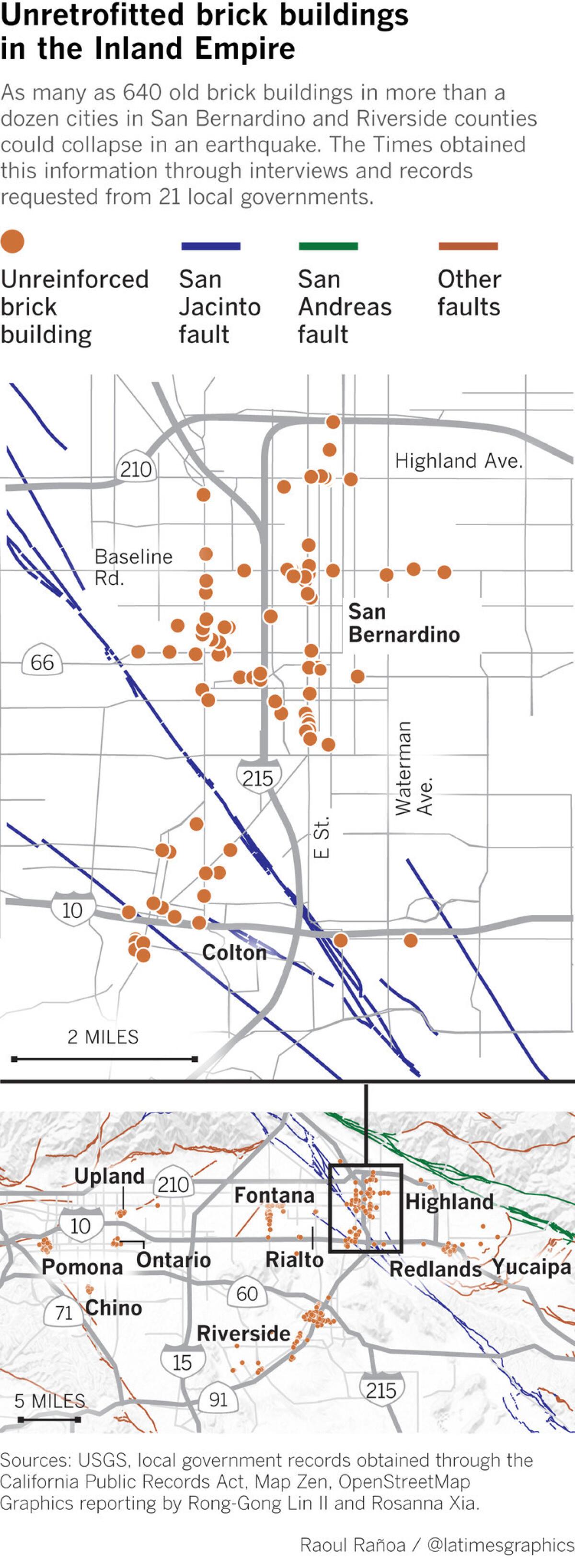

As many as 640 buildings in more than a dozen Inland Empire cities, including Riverside, Pomona and San Bernardino, have been marked as dangerous — but remain unretrofitted despite decades of warnings, according to a Times analysis of the latest building and safety records. These cities are far behind coastal regions of California, which have retrofitted thousands of buildings after devastating earthquakes exposed how deadly they can be.

The risks are all the more concerning because the Inland Empire is particularly vulnerable to a major earthquake.

Three of the state’s most dangerous faults — the San Andreas, the San Jacinto and the Cucamonga — intersect in this region east of downtown Los Angeles. The San Andreas alone, an ominous battleline visible from the foothills, is capable of unleashing a devastating magnitude 8.

Any shaking would be amplified by the precarious soil the region is built on — a basin of loose sediment that would rock like a bowl of Jell-O.

The Inland Empire is uniquely unprepared for a major earthquake, in large part because its economy has struggled in ways more-affluent coastal California has not. City officials and residents say myriad issues weigh on their day-to-days and seismic safety rarely tops the list.

Antonio Canul, a longtime restaurant owner in San Bernardino, shrugged off the risks and said there was no point in saving the city from an earthquake when it was already in such economic shambles. In the 34 years that he’s lived in the city, Canul said, he’s had more pressing matters to worry about.

“I’m just here to do business, feed people and make a living,” said Canul, who cooks, cleans and serves each day, starting at 6 a.m. in an old brick building downtown. “If you’re gonna die, you’re gonna die. Maybe it’s cancer, maybe it’s an earthquake.”

Then there are the other obstacles: Poor data upkeep. Building chiefs who stick around for only a few years. Little, if any, public pressure. In dozens of interviews and records requests, The Times found a trail of starts and stops by officials in each city to identify and update lists of old brick buildings. One list dated back 27 years; others were marked by hand or indecipherable.

While Los Angeles, San Francisco and others have charged ahead on retrofitting many types of vulnerable buildings, many here still have not tackled what structural engineers say is the most basic, most dangerous, most unsupported type of building.

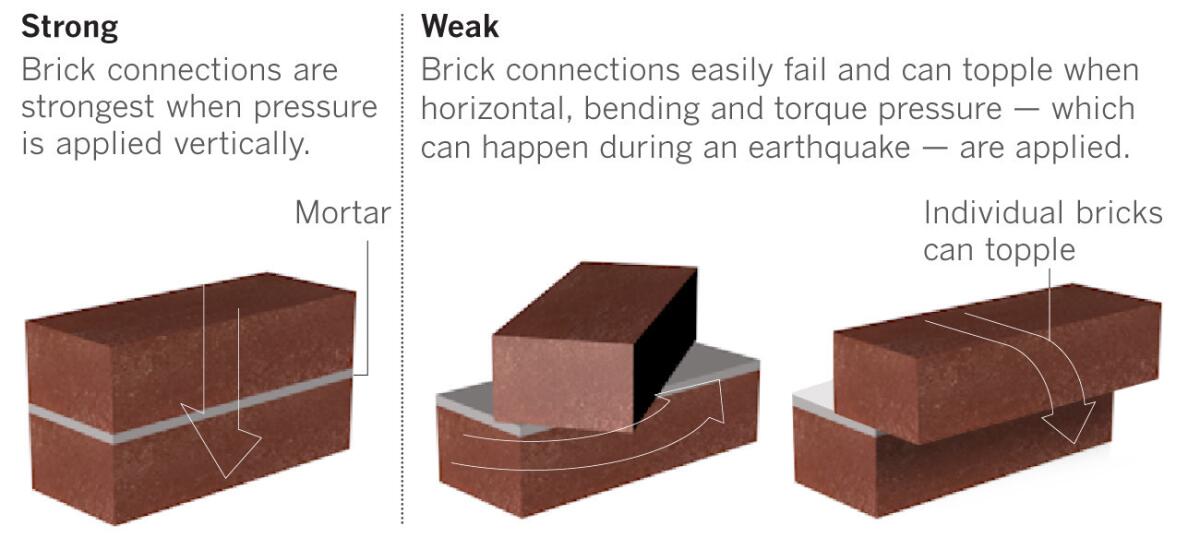

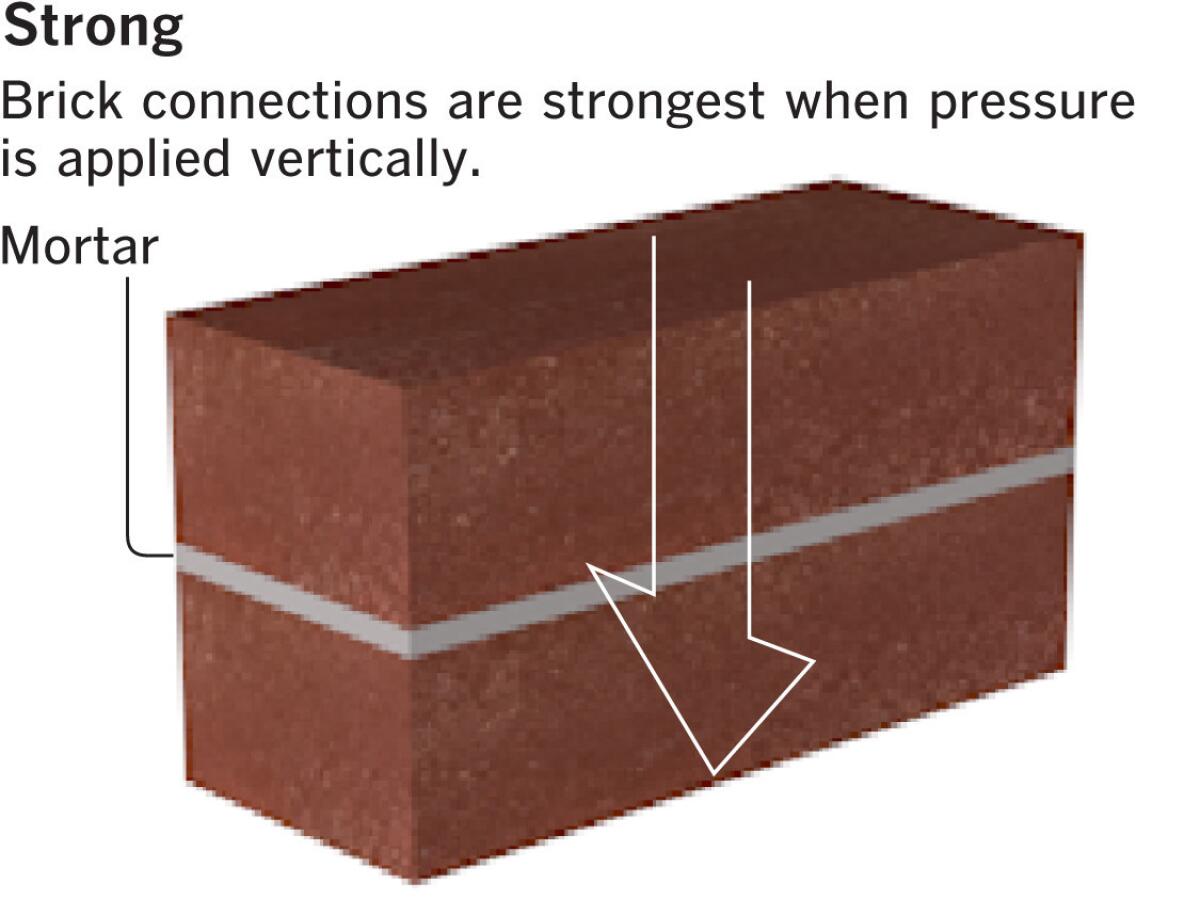

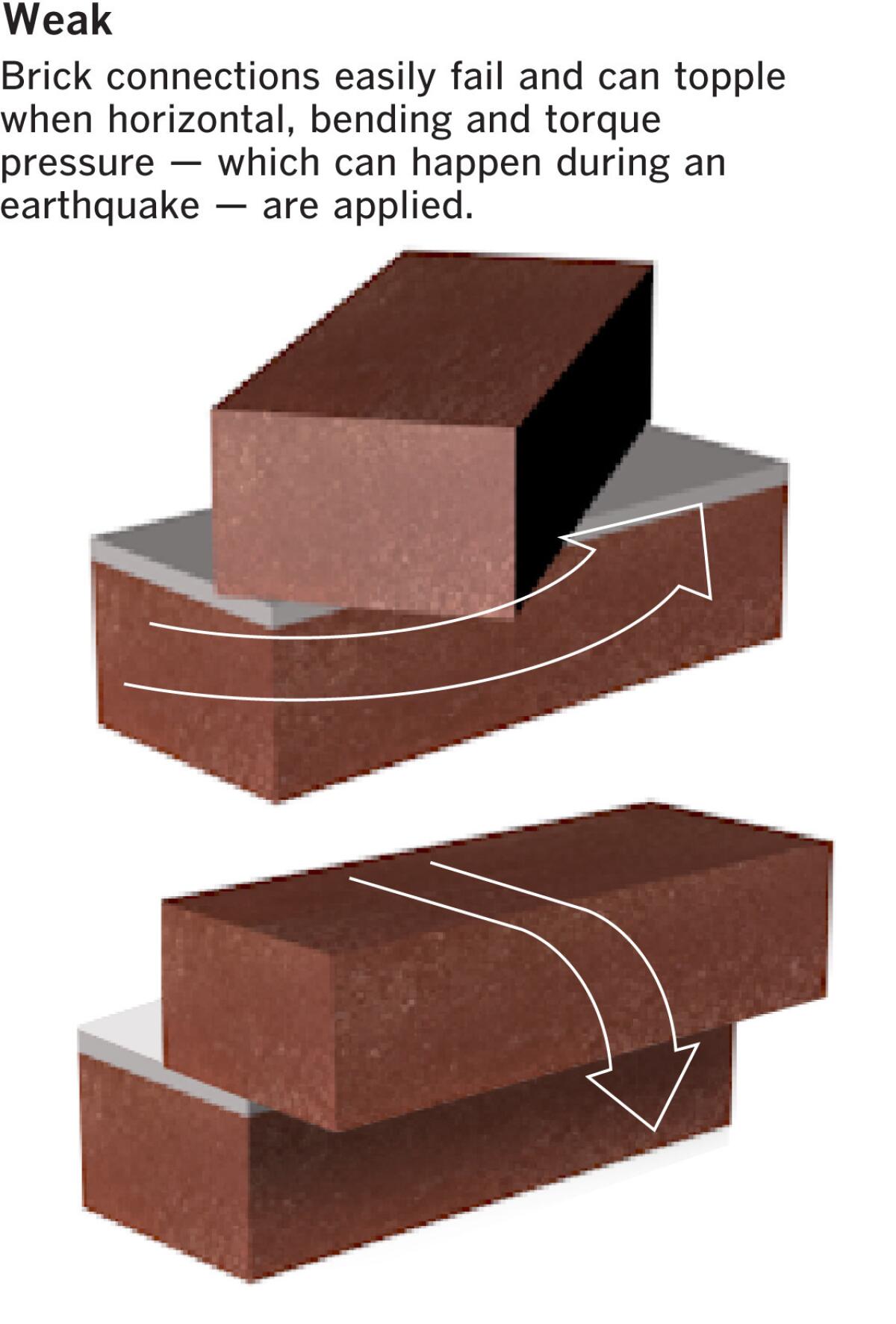

California learned the dangers of brick construction when a major earthquake struck Long Beach in 1933, crumbling schools, churches and shops. Some 120 people died. These so-called unreinforced masonry buildings, or URMs, are vulnerable because the mortar essentially crumbles apart during shaking, bringing down the roof and walls.

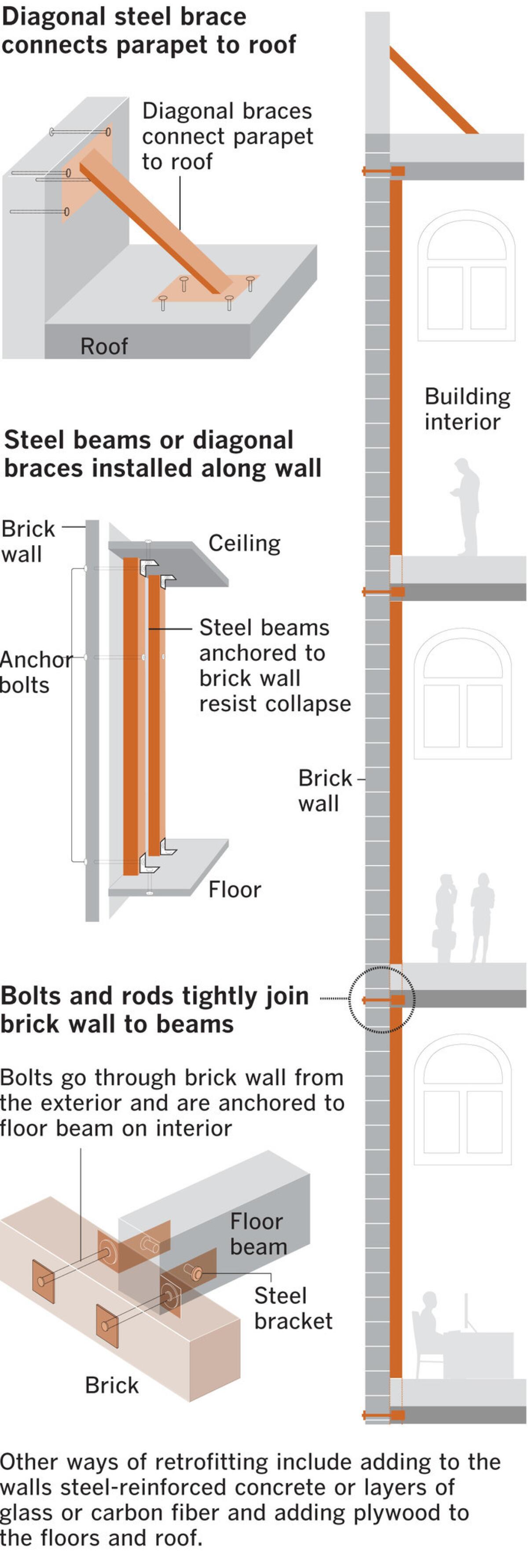

In-depth graphic: Why old brick buildings can collapse, and how they can be retrofitted »

Cities across California now ban this type of construction. URMs that had already been built were mostly left to fate. But as its history of destruction continued — Sylmar in 1971, Loma Prieta in 1989 — a number of cities found the political will to compile a list of addresses and force owners to either demolish or add reinforcement to their brick buildings.

When a magnitude 6.5 earthquake in 2003 struck downtown Paso Robles, the two people who died were found crushed under an avalanche of bricks outside an unretrofitted historic building. The roof had slid onto the sidewalk, taking the clock tower with it. (The city, which had a retrofit law on the books, had given the owner until 2018 to complete the seismic strengthening.)

“They are really dangerous. … Even with moderate earthquakes, we see — all the time — collapse of these structures,” said UC San Diego structural engineering professor Benson Shing, who has researched the subject extensively. “There’s no spine. You can see the blocks just one on top of another. So when you shake the structure, it will just rock and collapse.”

In Los Angeles, after three decades of chasing down the owners of 8,080 URMs, officials say there are now only three left in the city that still need to be retrofitted or demolished. When the Northridge quake struck in 1994, the retrofits proved lifesaving: Not a single person died in a brick building.

The Times started surveying Inland cities in the wake of the 2014 Napa earthquake, which once again exposed the vulnerabilities of brick construction. Reporters, under the California Public Records Act, requested URM data from 21 jurisdictions. Following these inquiries, a number of city officials restarted their efforts to identify which buildings remain at risk today.

“We have to deal with it one way or the other, sooner or later,” said Ramon Hernandez, who became Colton’s building official 18 months ago and has been retracing the steps of his many predecessors. Hernandez drove around the city in December and updated a building list from 1991 in response to a Times inquiry. He said he’s reached out to owners and is trying to find a solution.

Others have thrown up their hands, pointing to the same challenges their cities faced decades ago that are still holding them back today.

Forcing owners to retrofit or demolish these buildings just doesn’t make sense in a predominantly working-class region like the Inland Empire, some city officials said. Many treasure the area’s historical character, and a city could be put at an economic disadvantage if neighboring cities don’t enforce the same strict rules.

“The jurisdiction that does not require retrofit can outcompete their neighbor that does require retrofit when attracting new business,” said Mike Gardner, a councilman in Riverside, where the historic Mission Inn and some of its surrounding brick buildings have been retrofitted. In all, the city has as many as 160 URMs left, the most out of any city examined by The Times.“There is also a risk,” Gardner said, “that buildings that have not been retrofitted may be abandoned by their owners in economically depressed areas.”

Others shrug at the number of unsafe buildings. They say many are only occupied for a few hours each day and question whether retrofitting such old buildings — which might save lives but not necessarily the building after an earthquake strikes — is even worth it. It makes more sense to wait for real estate demand to kick in, they said, when new owners decide it’s more cost effective to tear these buildings down and build anew.

The city of Ontario at last count had 42 unretrofitted brick buildings. “That’s not a high number,” building official Kevin Shear said.

Seismologist Lucy Jones, whose work guided L.A. in 2015 to enact the most ambitious seismic safety laws in California history and is now helping dozens of smaller cities do the same, said she understands — but also questions — these economic arguments.

If you're going to use an economic argument, you have to ask: What's the value of human life?

— Seismologist Lucy Jones

“If you're going to use an economic argument, you have to ask: What's the value of human life?” she said. “URMs are the reason you have earthquakes in Iran that kill 60% of the population. Most of us don't have them anymore. And the idea that we do know exactly which buildings are the most dangerous and where the dangers will be … what’s the implication of a decision to not retrofit?”

In San Bernardino, which sits directly on top of the San Andreas, officials acknowledged the implications and said it’s time to do something about the risks. Despite the challenges posed by a five-year bankruptcy, a weary working community and spotty records on the oldest properties in town, building officials have tried to push ahead.

“It's a daunting task. A lot of people don't understand what a complicated issue it is. People just think, ‘We've known that these are high-risk buildings for 25 years, why haven't cities done anything?’ ” said Mark Persico, who took over the city’s building and safety staff in 2014. “One of the issues that we’ve had — because there's been a high turnover in staff as a part of the bankruptcy — is really coming up with a complete list of properties, because the city has started and stopped this process, I think like many cities have, since the early 1990s.”

By April, Persico and his team had whittled the list down to 89 buildings still in need of retrofit. Many are boarded up and vacant in the city’s downtown.

Tucked in an otherwise desolate stretch of aging brick buildings, Canul’s corner restaurant, along historic Route 66, is one colorful hallmark to what a bustling downtown could be. Steps were taken in the 1990s to retrofit this building, when the city had tried a mandatory retrofit law. Facing pushback and limited success, the city repealed the ordinance in 1999, and it is unclear today whether the restaurant retrofit was completed, according to city records and preliminary surveys by Persico and his team.

The current building owner on record could not be reached for comment.

Inside on one recent Wednesday, the lunch rush was lively. More than a dozen tables, along with the bar, were crowded with parents, children, police officers and government workers. An outdoor patio offered more seating along a painted brick wall.

Canul, dismissing the seismic risks, said the city needed to focus on more important problems than telling owners what to do.

“Fix the economy first,” he said. “Create more businesses around here. Create an environment for more people to come. If they do, small businesses like this are going to have money to rebuild these old buildings.”

Persico has hosted a number of community meetings to bridge this disconnect, broaching the idea of reviving a mandatory retrofit ordinance. Forcing building owners — most of them mom-and-pop business operators — to spend tens of thousands of dollars to retrofit was, and still is, unrealistic, Persico said. Unlike in Los Angeles, real estate values are so low that even taking out a commercial loan for a retrofit would be difficult.

The cost of retrofitting a brick building — which can involve using steel braces, rods and beams to hold up the bricks in a way that keeps them from coming apart during shaking — could cost an owner anywhere from $30,000 to more than $100,000.

Within the next year, Persico hopes to secure some form of grant to help owners pay for a percentage of the architectural or engineering cost of retrofitting.

Three ways to retrofit

Making old brick buildings safer can require more reinforcing material like steel. Think of a wooden table — it’s more likely to fall apart without long steel screws that keep it together when shaken, Hussain says.

A handful of neighboring cities — both wealthy and working-class — have overcome the economic pushback. Following a magnitude 5.2 earthquake that damaged numerous brick buildings, Claremont in 1991 mandated all 33 of its URMs retrofitted or demolished. Rancho Cucamonga enacted a law that year forcing owners of URMs to retrofit or demolish within three years of notification.

By 2006, the city was down to 22 unretrofitted brick buildings. Today, just one — fenced off and red-tagged — remains.

In Chino, building officials in 1988 identified about 30 unsafe buildings and chipped away at the issue. Using redevelopment money, the city purchased a number of brick buildings in its downtown, demolished them and turned the empty lots into a community park and a new senior living complex.

For the remaining unretrofitted brick buildings, city officials bolted large signs by each entrance, declaring in English and Spanish: “In the event of an earthquake, this building could be subject to structural damage that could cause death or injury to its occupants and/or persons near the building exterior.”

One owner, hoping to attract more high-end retail tenants, took all the steps to retrofit his building and made a show of removing the placard during a ceremony in 2007, recalled community development director Nick Liguori. “That was a big deal to him — to get that building retrofitted so he could take that placard off.”

These placards were placed in accordance with a decades-old state law that requires owners to post warnings outside unsafe brick buildings — but cities are not required to enforce the law, and many in the Inland Empire do not, according to interviews and spot checks by Times reporters of a number of old brick buildings.

The lack of institutional memory in many of these cities is a major problem. Building officials tend to come and go, handing off old notes and addresses from one to another like a baton, with no finish line. Yucaipa’s building official currently is also the top building official for another city and the interim chief for a third.

Back at Redlands, Corrie Kates has been coming in twice a week as the city’s latest building official. A third-party contractor, he replaces the former full-time building chief, who left last year.

Some of the brick buildings downtown have been retrofitted, Kates said, and any owner who wants to make significant renovations would be required to include a seismic update. But the reason there remain so many unretrofitted buildings in the city is simple.

“The owners don't have the money to retrofit them, and there’s no funding out there to help,” he said. “If there were public funds available, then cities would go make an effort to promote people to retrofit."

Kates said it was useful for the city to have its list of 74 addresses, last updated 13 years ago, that are considered hazardous.

If the alarm bells start ringing and the ground starts shaking, he said, fire and rescue officials will know where to check first.

Twitter: @RosannaXia | @ronlin | @ranoa

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.