L.A. schools lost $15 million on Day 1; attendance improved slightly on Day 2 of the teachers’ strike

As the first Los Angeles teachers’ strike in 30 years stretched into its second day, attendance ticked up slightly — about 20,000 more students went to school Tuesday — but remained at about a third of the district’s total enrollment.

The school district’s top official lamented that the walkout already had cost millions in state funding on Day 1; 163,384 students showed up for class — or some semblance of it — on Day 2.

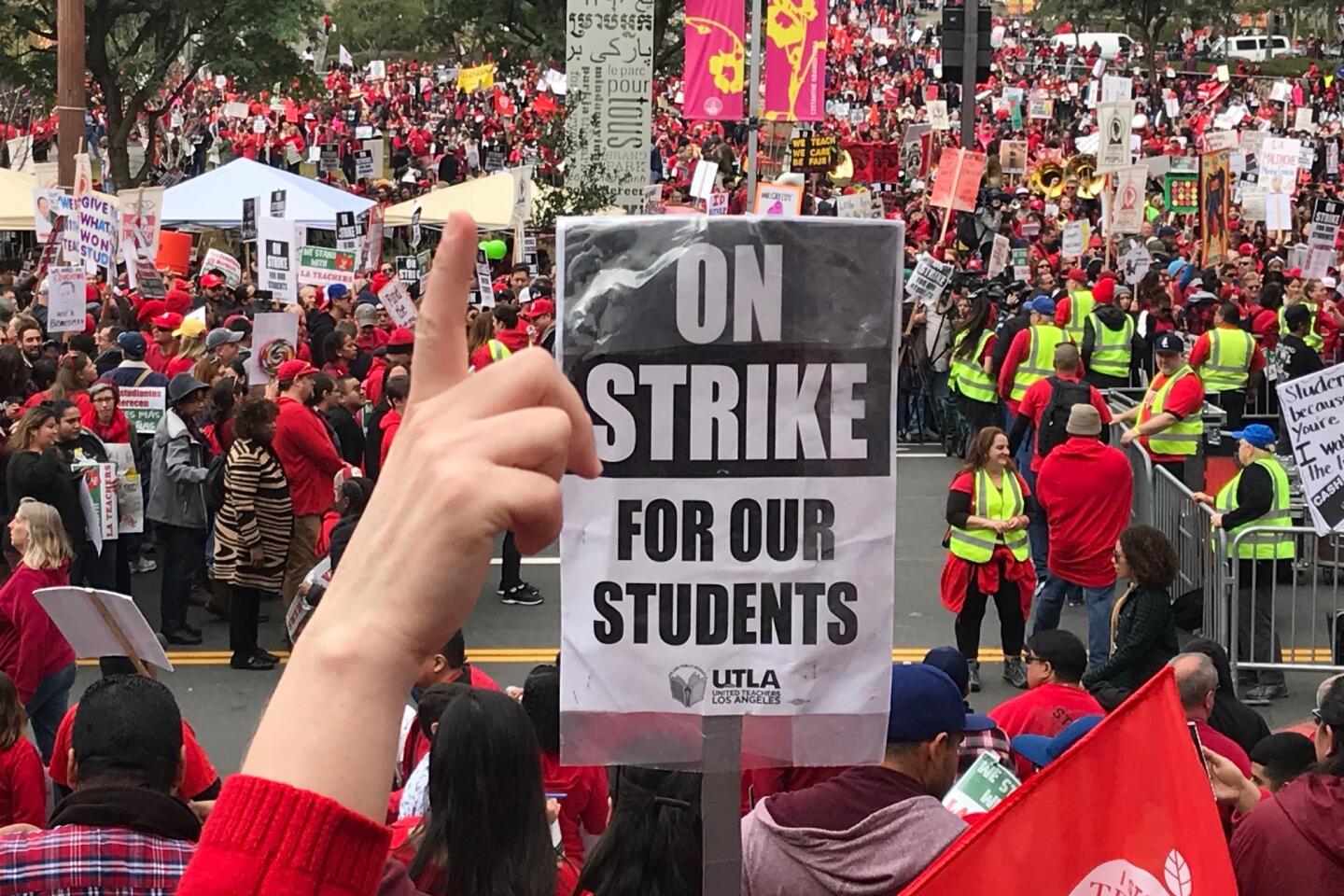

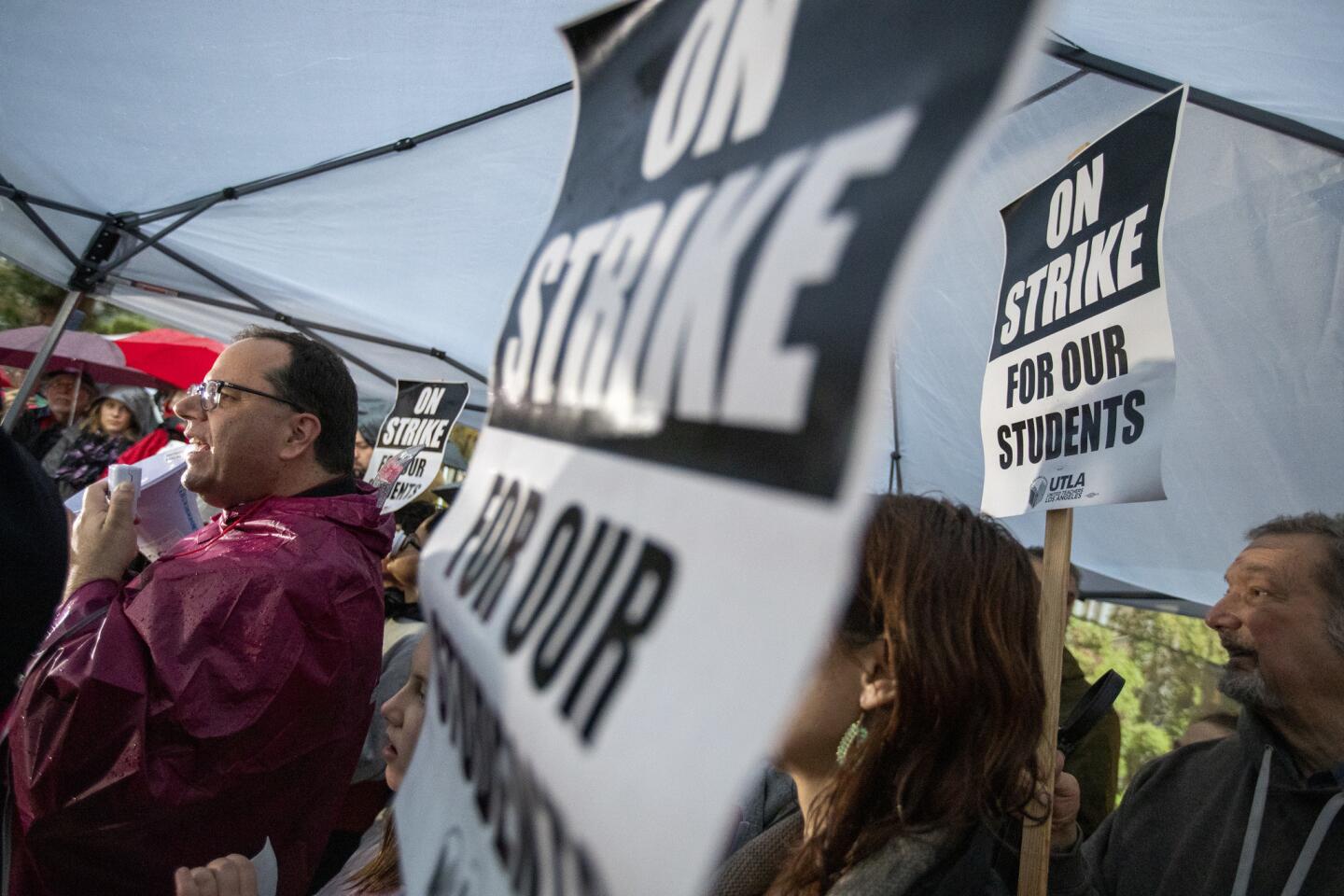

Teachers, meanwhile, returned to the picket line and then converged downtown for a rally to protest the growth of charter schools, which their union, United Teachers Los Angeles, has blamed for draining funds from the district. They remained out even as the week’s second strong storm moved into the region.

Los Angeles schools Supt. Austin Beutner, in a morning news conference, said the first day hit hard with only a third of the district’s students showing up for school. That cost the school system about $25 million in state funding tied to enrollment, he said. Subtract unpaid wages for the strikers of $10 million, he said, and that amounts to an estimated one-day, net loss of $15 million.

The union, which wants better wages, smaller class sizes and more support staff at schools, has argued that the Los Angeles Unified School District has the money on hand to meet its demands, even while saying that the school system also needs to get more state funding.

Beutner said the union and its 31,000 members who walked off the job should join with the district in pushing Sacramento to better fund schools.

“Let’s build on the renewed attention on public education in our community,” he said. “Let’s bottle it. Let’s put it on our buses and let’s go to Sacramento.”

Voices of the LAUSD strike: Teachers and parents speak out »

Negotiations between United Teachers Los Angeles and the nation’s second-largest school district broke off late Friday after more than 20 months of bargaining, with no resolution to the educators’ demands. District officials have said they don’t have the money to cover everything teachers are asking for, while union leaders have accused the district of “hoarding” funds.

Alex Caputo-Pearl, president of UTLA, said Tuesday that members are “prepared to go as long as it takes” to get a fair contract. He joined picketers at the Accelerated Schools in South Los Angeles, a small charter school network whose educators stopped working Tuesday in their own strike for improved working conditions. The action is the first strike by charter teachers in California and only the second in the nation, according to UTLA.

“This has been already an historic week for educators and for public education in Los Angeles,” Caputo-Pearl said.

Teachers at Accelerated have their own contract with the charter operator, but he said the two strikes have a few common themes.

“Accelerated management has money to take care of the issues on the table,” Caputo-Pearl said. “Also in common is that Accelerated management is being driven by ideology, looking at teachers as disposable and not as indispensable. We’ve got to change that.”

By mid-morning, the area around the intersection of 1st and San Pedro streets in downtown Los Angeles was filled with teachers and supporters, chanting and waving signs outside the offices of the California Charter Schools Assn.

Charters are privately managed and, while most are nonunion, UTLA represents about 1,000 charter school teachers. Caputo-Pearl has said existing charters that are struggling with enrollment also are being hurt by the “grow at any cost” strategy of some charter advocates.

Fiona Engler, magnet coordinator for Paseo Del Rey Elementary, a magnet school in Playa Del Rey, has been with LAUSD since 1985. She has seen the damage that charter schools have wreaked on the public school system, she said. Charters, she said, “cherry pick” students and send those with discipline problems back to public schools.

She said she also is striking for less “hard-core testing,” of younger kids in lower grades.

“Imagine just taking a test that just goes on for pages and pages and pages on an iPad,” Engler said, describing current testing requirements. “And just goes on for hours.”

Jackson Downey, 15, a sophomore at Cleveland High School Humanities Magnet in Reseda, rode the Metro downtown from the San Fernando Valley with four friends to support teachers at the rally. Jackson — holding a sign that read, “Without teechars are sines wil luk like dis”— said he thinks charter schools are detrimental to the public school system.

“I see it as the end of public schools,” he said.

The two days of walkouts have proved to be a massive disruption for hundreds of thousands of students and their families. The vast majority of the district’s parents and guardians are low income, and many have grappled with choosing between missing work to watch their children or sending them into an unknown situation at school.

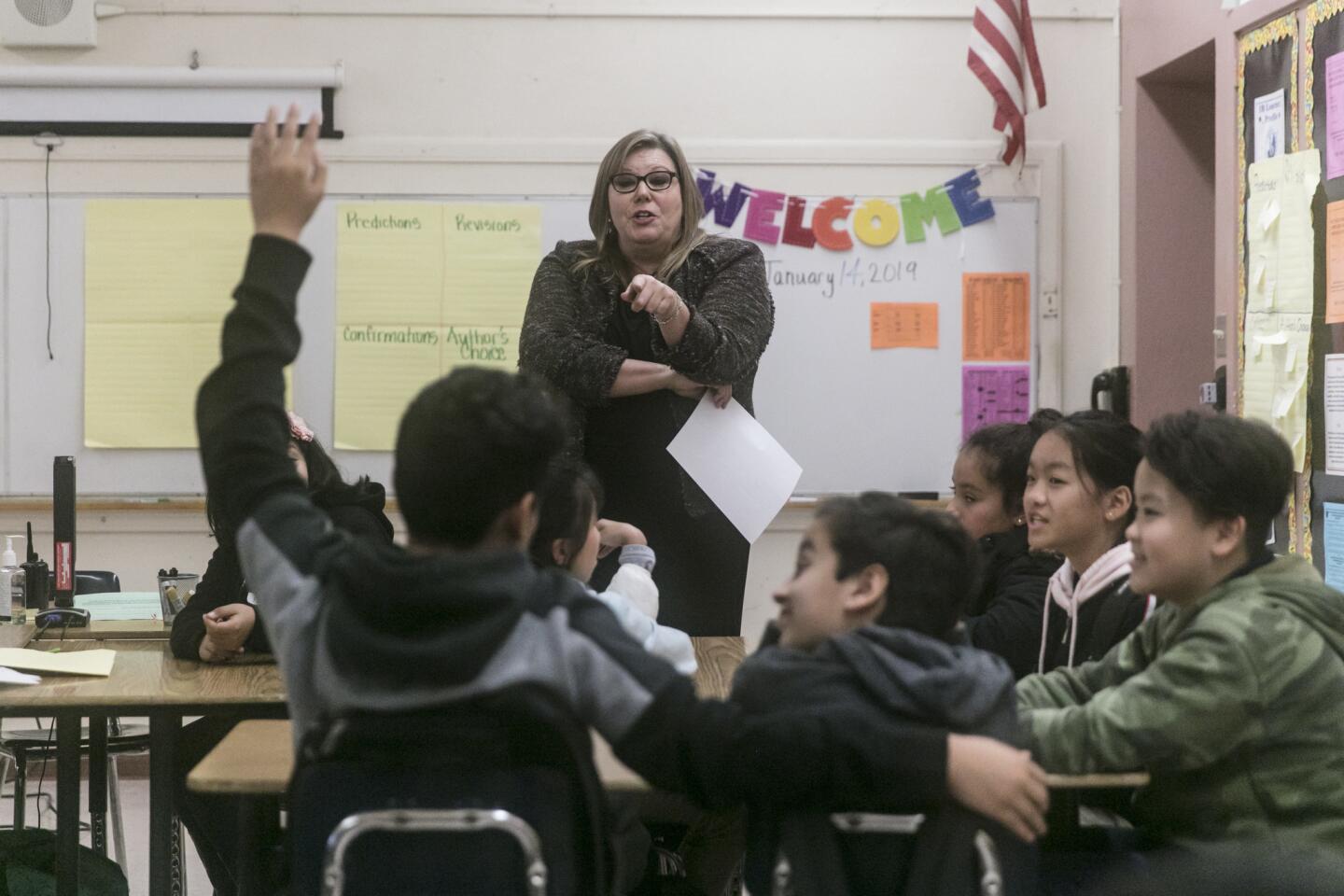

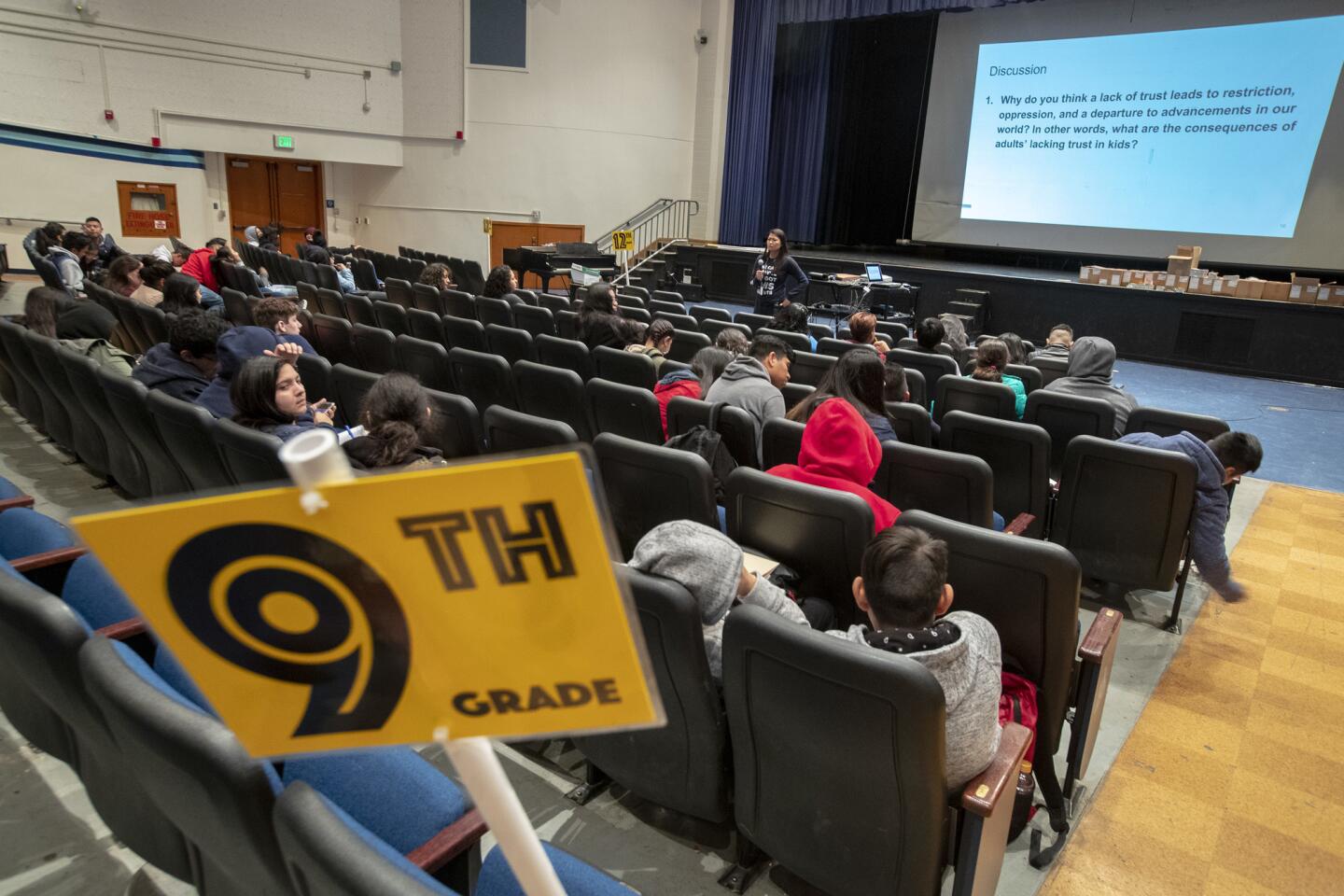

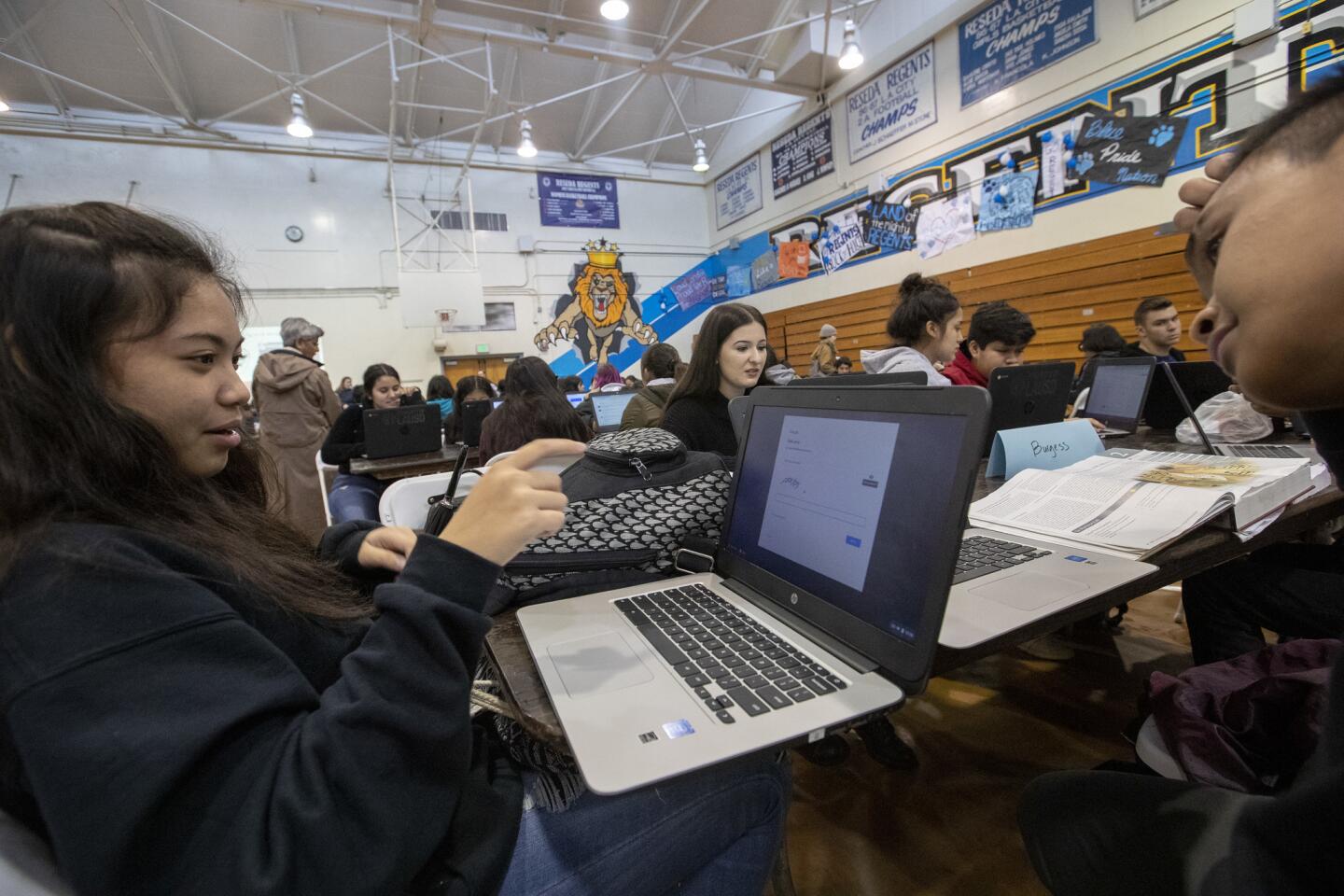

With K-12 schools remaining open during the strike, but preschools closed to most students, skeletal staffs have crammed students together to try supervising them in larger groups and struggled to keep them engaged as teachers march outside.

About 140,000 students attended Los Angeles schools on Monday, down from about 450,000 on a typical rainy day. Beutner pointed to two schools — Virgil Middle and Telfair Elementary — where attendance was slightly higher, as an example of students relying on the district for shelter and a warm meal.

At Telfair, he said, about 20% of the students are homeless. At Virgil, 100% of families are living in poverty. On Monday, 60% of Virgil Middle School’s students attended class along with about 40% at Telfair.

“They came for shelter from the rain. They came for a warm meal and a secure, welcoming environment. And of course they came to learn,” Beutner said.

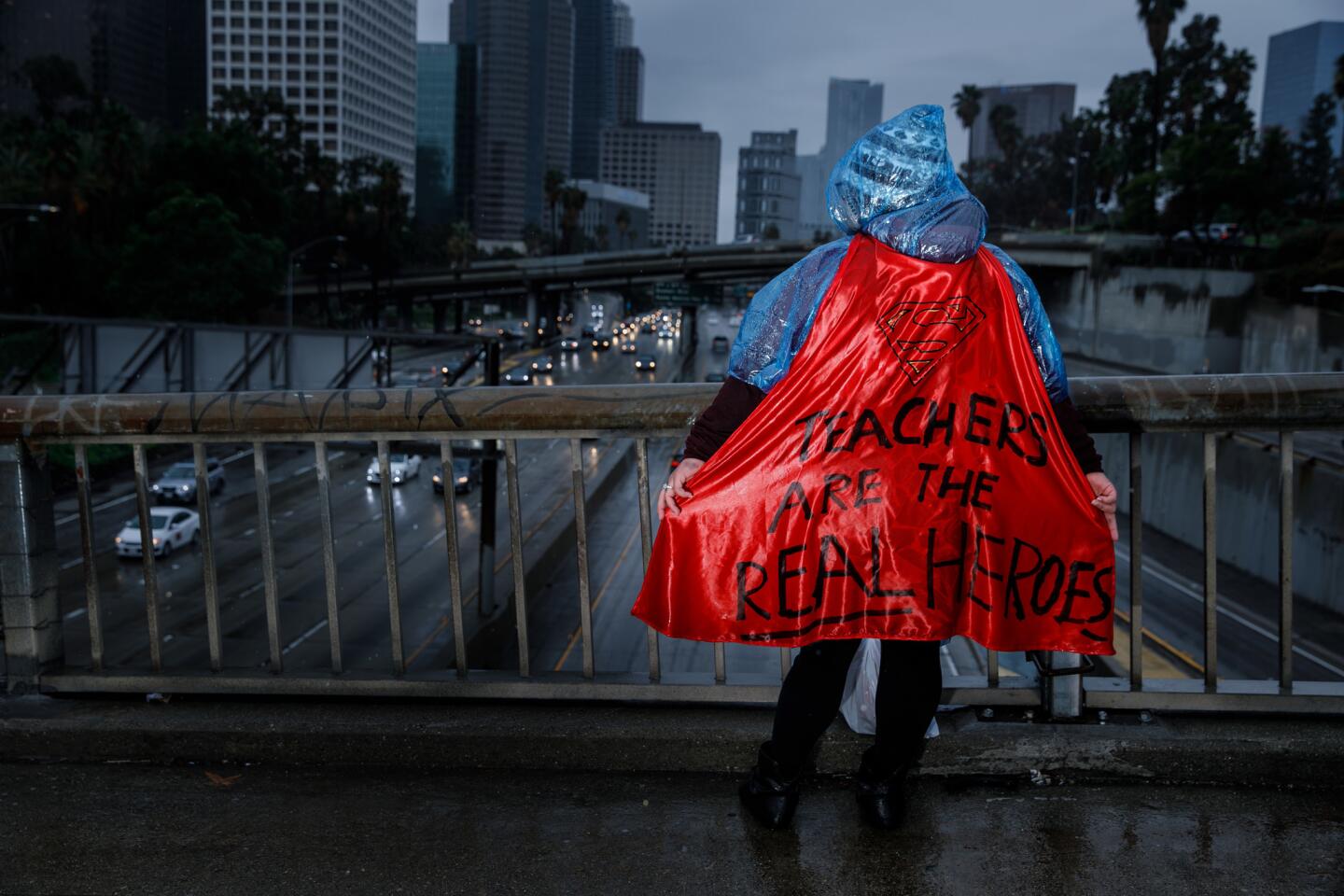

On Tuesday, teachers formed picket lines early, while it was still dry but came prepared for the rain that would soak them in the afternoon. Burroughs Middle School drama teacher Jennifer Heath was ready for the looming storm. She went to the Army surplus store on Monday night, after a day of picketing in the rain, and bought more waterproof gear.

Outside the Hancock Park campus with more than two dozen teachers, Heath’s golden retriever Fenton wore a red poncho as he lay on the sidewalk next to a Maltipoo named Bailey, sporting a bandanna that said “strike therapist in training.”

Heath fought back tears as she talked about how unnatural it was not to be able to work with her students and watch over them during the day.

“We need to invest in public education,” she said, holding up a sign with “FUND THE FUTURE” in red block letters.

Christina Silva, a special-education teacher, said she’s worried about her students, many of whom have individualized education plans that require one-on-one attention from teachers or aides assigned to them.

“How do we close the achievement gap when we’re out here?” Silva said. But in the long term, getting smaller classes for her students will help them emotionally and academically, she said.

Dennis Gonzalez, a student at James Monroe High School in North Hills, said his parents have been bombarded with phone calls and text messages, warning them that their son would be penalized for staying home during the strike and insisting that school was the safest place to be. Still, Gonzalez chose to support his teachers. Their concerns are his concerns, he said after marching downtown on Tuesday.

“It’s not just about the teachers — it’s about us,” said Dennis, 17. “It’s even about our kids, one day.”

Some students who missed school Tuesday said they still planned to do homework. After a full day of picketing and marching with her teachers, Venice High School junior Makena Cionio planned to catch up on her four Advanced Placement classes.

Her teachers treated the students “like adults,” she said, and gave them plans so they could keep with their studies.

Jose Saban, 16, said his day at Hollywood High School was anything but normal.

“For instance, in math, they taught us statistics. But some of us don’t take statistics, so we had no clue what we were doing,” Jose said. He went to school because he plays volleyball and is a member of the cross-country team, and said he wouldn’t be allowed to participate if he was absent too much. Jose, like many other students, said he would benefit from smaller class sizes.

By 2:30 p.m., more than 100 teachers, parents and students gathered outside of Hollywood High in the rain, many of them holding signs that read “our students deserve smaller classrooms.”

The issue of smaller classroom sizes has become a critical issue for union members, such as Hollywood High history teacher Kelly Bender who was on the picket line Tuesday.

“Teachers are dedicated. Teachers become teachers because they want to affect the future and make a difference in human beings’ lives, and we’re passionate about that,” she said. “That’s why we stand in the rain. We’re used to horrible conditions and we can handle more, but we shouldn’t have to.”

Times staff writers Matthew Ormseth and Sam-Omar Hall contributed to this report.

Twitter: @Hannahnfry

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.