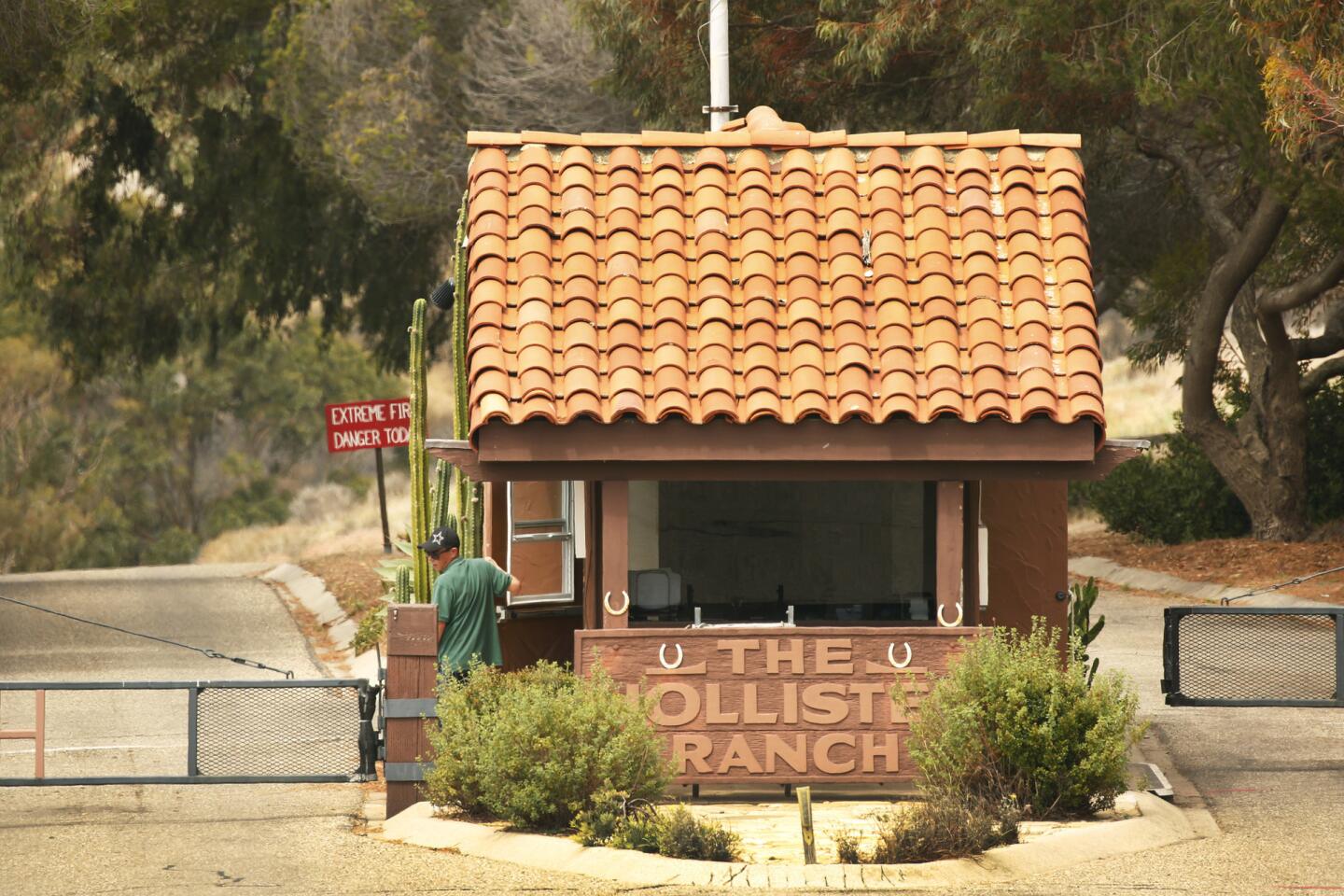

The fight is on at Hollister Ranch, as coastal officials delay development in push for beach access

After more than three decades of stops and stalls, the state this week made clear the fight for beach access at Hollister Ranch is far from over.

Coastal officials revived efforts to create a long-delayed public path while also preventing a family from building on its slice of the ranch until all visitors can enjoy the 8.5 miles of secluded Santa Barbara County coastline.

Earlier this year, the fight for access to some of the state’s most unspoiled beaches seemed like a done deal in favor of ranch owners, who have long contended the environment has benefited from their private stewardship. A controversial state deal ceded a contested claim to access by land, and a veto by Gov. Jerry Brown last month was cheered by Hollister as a victory.

But mounting outrage from beachgoers has kept the pressure on.

“Because of the public outcry, I think every commissioner is of one mind that we are resolved to finally, one way or the other, get real public access by land through Hollister Ranch,” California Coastal Commissioner Aaron Peskin said.

“As a matter of policy, this commission is resolved to say that either Hollister Ranch is going to provide public access or we are going to interpret the law to say that there should be no future development there.”

The commission’s latest strategy relies on an access program for Hollister Ranch that the state had adopted in 1982 after a complicated legislative history and a long standoff with resistant landowners.

With 14,500 acres connected only by private roads, ranch owners at the time had argued it was impossible for each of them, as required by the Coastal Act, to provide a public route to the beach every time they sought a permit to build.

They challenged this in court, saying that individual lot owners were unable to do so because the common roads were controlled by a third party — the Hollister Ranch Owners Assn.

So lawmakers added a special section to the Coastal Act, allowing owners to pay a fee instead that would fund a ranch-wide access program that the state would implement “as expeditiously as possible.”

The 1982 program included a walking trail and bicycle lane that would run parallel to the ranch's main private road. To minimize the number of cars — in the interest of privacy and environmental protection — a bus would operate from nearby Gaviota State Park to six Hollister beaches, where there would be picnic areas and bathrooms.

Facing pushback, officials agreed to implement the plan in three phases. A cap was also set on the number of people allowed on the ranch each day, beginning with 100 people in phase one and a maximum of 500 in phase three.

Read the 1982 Hollister Ranch coastal access plan »

But “as expeditiously as possible” turned into 36 years and counting. The standoff continued until the issue faded from institutional memory and public scrutiny.

For decades, many Californians accepted without question that Hollister Ranch was a private oasis that sometimes granted access to scientists, academics, historical societies, environmental groups and schoolchildren. Owners have said managing access is what has allowed the ranch to remain environmentally special.

The push for greater access had gone quiet until this year, when coastal officials agreed to a settlement that kept the ranch’s coastline closed off to everyone but landowners, their guests, select groups and those strong enough to paddle or boat in through treacherous waters.

After a flood of public outcry, lawmakers introduced legislation that would have recommitted the state to the 1982 access program and clarified a funding source. It also laid the foundation for more aggressive strategies, such as acquiring private land for public use through eminent domain.

The governor acknowledged the spirit of these efforts, but in a veto message last week said the 1982 plan was outdated. He urged officials to draft a more contemporary strategy.

Coastal officials said the 1982 plan laid a strong groundwork and remains relevant today. If anything, they said, there’s room to update the program to provide greater access.

At Wednesday’s commission meeting, held in downtown San Diego, the agency announced it has created a team to update the program as quickly as possible. The goal is to have something ready early next year — in time for the next legislative session, executive director Jack Ainsworth said.

Monte Ward, president of the ranch owners group, which represents more than 1,000 owners, cited Brown’s veto and said in a statement that “the 1982 Hollister Ranch Access Plan is outdated. We hope that the State reaches out to us to coordinate regarding the contents of a revised plan.”

Meanwhile, officials at the State Lands Commission have been looking into their own legal authorities, which include eminent domain proceedings, land exchanges or negotiating new boundary lines.

The Coastal Commission’s commitment to finish what was promised in 1982 came the same day officials voted unanimously to overrule a permit that had been issued by Santa Barbara County — citing for the first time in decades that a condition of any permit at Hollister Ranch, under the Coastal Act, is providing beach access through the ranch in a timely manner.

The move marks yet another front in the fight for access.

Mark Shields, whose family sought the permit to build a house, guesthouse and footbridge, said they had spent years coming up with a reasonable project, followed all the rules, and are now unfairly being swept into this larger battle at the ranch.

“We respect the fact that coastal access is the right of all Californians. We understand that the larger issue in play, the question of Hollister Ranch access, is the source of our troubles,” Shields wrote in a letter to the commission. “Please know that we are simply a family who has worked hard, loves California, and wants to complete a heartfelt family compound before we are too old to enjoy it.”

His family’s project, he said, is being overruled by “what appeared to be solely political reasons, citing issues which we have no control over nor ability to rectify.”

The ranch owners association echoed these sentiments, saying in a statement that the permit had been approved without opposition from Santa Barbara County. The group added that “the Shields’ parcel is over a mile inland, so the Coastal Commission appeal seeks public beach access over land that the Shields do not own.”

Read more: Coastal advocates challenge deal that bars public from reaching Hollister Ranch by land »

These pleas drew little sympathy from coastal advocacy groups, which are fighting for greater access through a court intervention. In their own letter to the commission, advocates said that “public coastal access at Hollister Ranch is long overdue, and the County’s mishandling of [coastal development permits] including [the Shields family’s] has hindered establishing that access.”

Peskin, one of the commissioners who initiated the vote to overrule the permit, said this issue has gone on for almost four decades and the writing is on the wall.

“If there was one message that came out of today’s meeting,” he said, “it's a very bright message to the Hollister Ranch Owners Assn. that it's time to work things out.”

Interested in coastal issues? Follow @RosannaXia on Twitter.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.