Joshua Tree couple are released from jail but still face child abuse charges

Reporting from Joshua Tree, Calif. — It started as a child’s fort — some plywood and a tin roof on a five-acre desert plot, put together by a homeless boy whose parents had long planned to build a home on the land.

There was one room at first, a place where the boy and his younger sister could play store, said their mother, Mona Kirk. Then the boy wanted a room for himself, she said. His older brother wanted one, too.

Stuffed with mattresses, toys and other furniture, the four-foot-tall fort grew to about 200 square feet. Over time, the family would sleep there occasionally, when they weren’t sleeping outside or in a home in town the father cared for.

“His father checked it out to make sure it was safe for us to be in there,” Kirk said. “The children were always safe.”

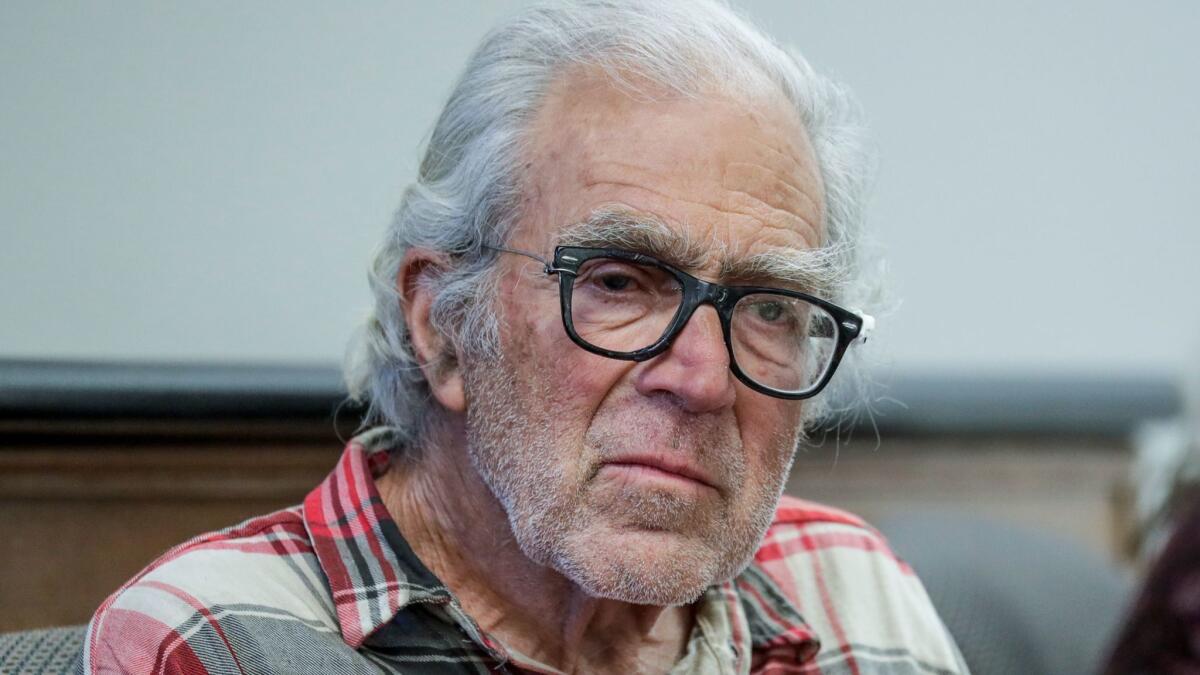

San Bernardino County sheriff’s deputies who came across Kirk, 51, her husband, Daniel Panico, 73, and their three children last week saw it differently. Kirk and Panico were arrested and charged with child abuse; the children, ages 11, 13 and 14, were removed by Children and Family Services.

On Tuesday, a San Bernardino County Superior Court judge ordered that the parents, who had been held on $300,000 bail, be released on their own recognizance.

They walked out of the sheriff’s Morongo Basin Station in the late morning and were greeted by dozens of supporters who carried signs saying “Being Homeless is not a Crime.” Kirk and Panico said they were relieved to be free. But they each still face three felony counts of child abuse and their children remain in county custody.

The case has raised questions about the responsibilities of homeless parents, as well as the duties of law enforcement officials who encounter families in precarious circumstances. It comes at a time when homeless advocates say it is increasingly difficult for struggling families to find homes in this popular tourist destination.

Peggy Stewart, an adjunct professor of social work at USC and an expert in child abuse, said it is important to know whether the parents could have done more to provide for their family.

“The key is were these kids put at risk unnecessarily?” she said. “Because the living conditions obviously don’t rise to the standards of a quality of life that a child deserves. So what did the parents do to mitigate that situation? Did they seek out help?”

“If they didn’t avail themselves of the resources out there and they had the capacity to do so, then they were negligent,” she said.

Friends say the parents did the best they could in difficult circumstances. The children were involved in the community and their parents are anything but abusive, they say.

“Daniel and Mona are some of the most gentle people you’ll ever want to meet,” said Diane Mann of Palm Springs.

Kirk and Panico bought their plot of desert land just outside of Joshua Tree National Park in an online auction about 15 years ago and had dreams of building a dome house, Kirk said.

In an interview Monday night at the Morongo Basin Station, Panico said the family at times slept in a trailer on the property. Other nights they slept outside, or in a Joshua Tree home where he worked as caretaker. And sometimes Kirk and the children slept in what Panico called “the hut,” the shelter built by his 13-year-old son.

“It’s like where do you live? We live here and there,” he said.

Kirk said the family took in cats that, despite their best efforts, kept multiplying. The family eventually gave their trailer over to the cats, so they would be safe from coyotes, Kirk said.

Deputies found dozens of cats living on the property, authorities said.

“We did not want to dump them in a shelter because we loved them,” Kirk said.

Panico says he is an inventor and was working on an invention that he hoped would generate money for his family. Online records show a Daniel Panico was granted a patent in 1976 for a whirling children’s toy and has an application, submitted in 2016, for a “device for production of a net impulse by precession.”

Kirk used to run a program for children but stopped working when they had their family, Panico said. She now home schools their children. Their daughter is in ballet and their sons have played soccer, Panico said. The oldest has a photographic memory and can remember everything he reads, he added.

While in custody, Panico wrote a description of what happened the day sheriff’s deputies showed up at his home, and shared it with a reporter.

It was the 13-year-old’s birthday, he wrote. Kirk and the children were asleep in the fort when they were rousted by officers shouting for them to come out, Panico said.

“The officers look around decide we are criminals,” Panico wrote. “Everything is fine for the kids. There is plenty of food, clean water, clothes, a place to sleep, go to bathroom. But we look bad. Trash all around. It blows in the wind, etc. We are poor.”

“Our family is torn apart,” he wrote.

Deputies said they encountered a situation that was simply not safe or suitable for children.

There was no electricity or running water. There were mounds of trash and human feces throughout the property. There was not enough food for the children.

Panico said he wasn’t aware of many resources available to families like his, though he said he perhaps should have known more. He said he doesn’t believe in government assistance.

“I don’t believe in going for public resources,” he said. “I believe in doing things independently.”

“We are just minding our own business, trying to raise three children on very little money, not wanting to impose on anybody,” he said.

Wayne Hamilton, a homeless liaison for the Morongo Unified School District, who has worked on homeless issues in the area for 13 years, said that although there may have been some resources the family could have taken advantage of — such as food stamps or cash aid — their options were limited.

The closest homeless shelter is about 75 miles away in the Coachella Valley, he said. And the wait for low-income housing can last years.

Homelessness and the need for low-cost housing around Joshua Tree is a growing problem, in part because the popularity of the national park has led many homes to be repurposed as short-term vacation rentals, driving up the cost of housing, Hamilton said.

A lot of families now double up in single-family homes, he said.

On Tuesday, Hamilton said he met with Kirk and Panico to offer help.

Hamilton said he did not know enough about the family’s circumstances to say whether the parents could have done more. But he said the outpouring of support from the community is a sign they were trying.

Maria Foscarinis, executive director of the National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty in Washington, D.C., said she read about the case and found it similar to many others.

“Of course children should not be living in a shack and they should not be living in these conditions,” she said. “The question is what is the solution? Taking the children away is often not the best solution.”

Kirk and Panico are expected back in court next week. For now, the couple will stay with friends.

As they left the courthouse, Kirk said she was eager to “get everything tidied up and … go on with life.”

She said she would like to tell her children, “I love you with all the hearts in the world.”

For more Inland Empire news follow me @palomaesquivel

UPDATES:

8:05 p.m.: This article was updated with additional interviews.

10:15 a.m.: This article was updated with the couple’s release from jail.

This article was originally published at 9:25 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.