For families of Manson victims, ‘We went from “Happy Days” to hell in one weekend’

When he was a kid, Lou Smaldino loved spending time at his grandmother’s home, rolling down the hill in the front yard with the other grandkids at her Los Feliz home.

When he and his first wife got married, they lived in a small house behind his grandmother’s garage. His grandmother would bring over dinner, knowing how broke the young couple was. Smaldino, 75, can still remember every room of that house on Waverly Drive.

Eventually, his Uncle Leno and Aunt Rosemary moved into the family home, where on Aug. 10, 1969, they were murdered by Charles Manson and his followers.

In the home where Smaldino and his family had found boundless joy, the Manson “family” used the LaBiancas’ blood to write “DEATH TO PIGS” on the wall and refrigerator, and “HEALTER SKELTER,” the misspelled title of a Beatles song.

“The fork that they stabbed Leno with was from the carving set we used for our Thanksgiving and Christmas dinners,” Smaldino said. “I can see that… To this day, I can see that in my mind.”

On Sunday evening, when Smaldino got the call from a prison official that Charles Manson was dead, at first he thought it was a prank call. He gets at least one of those a month, with someone on the other end making a Manson joke.

When he realized the call was real, Smaldino did feel a sense of relief – followed by a sense of sorrow. The murders forever changed his family.

Neither Smaldino’s once joyful grandmother nor his mother ever seemed happy again. The family business — a grocery store chain with about 18 markets across Los Angeles — eventually closed, as no one was left to run them. That had been Leno’s job, working alongside his brother, Peter.

“The family basically wasn’t the same after that,” Smaldino said. “... We went from ‘Happy Days’ to hell in one weekend.”

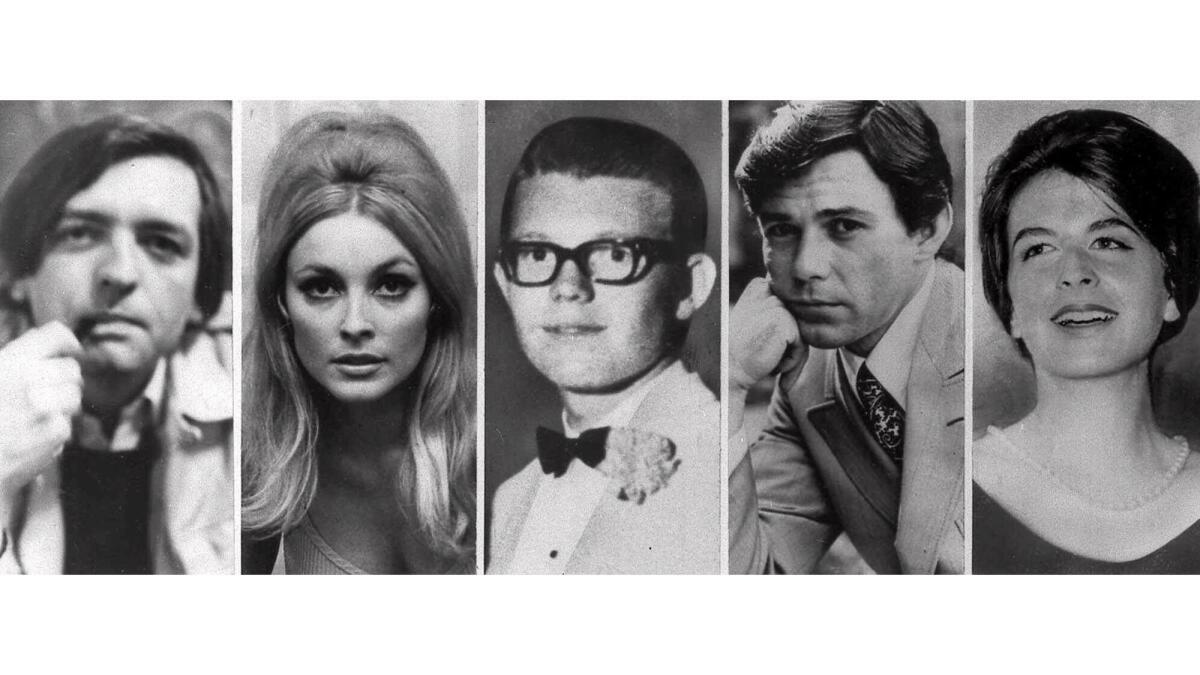

The five victims slain at the Benedict Canyon estate of Roman Polanski: from left, Voytek Frykowski, Sharon Tate, Steven Parent, Jay Sebring and Abigail Folger.

‘I literally felt like vomiting’

For almost 50 years, Manson and his followers have remained at the forefront of many Americans’ minds as their violent, tortuous rampage has been retold in books, films, podcasts and more.

But for the victims’ families, Manson’s legacy as a counterculture icon is a bastardized version of history that ignores their pain and mocks their loved ones.

That narrative, the families argue, ignores the people who can’t speak for themselves: Sharon Tate, an actress who was 8 ½ months pregnant; Jay Sebring, a Hollywood hair stylist; Voytek Frykowski, a friend of Sharon Tate’s husband, director Roman Polanski; Abigail Folger, Frykowski’s girlfriend and the heir to the Folger coffee fortune; Steven Parent, an 18-year-old who was visiting a resident at a guesthouse on the estate where Tate and Polanski lived; Gary Hinman, a musician; Donald “Shorty” Shea, a horse wrangler at the Spahn Movie Ranch; and Leno and Rosemary LaBianca, owners of a chain of Los Angeles grocery stores.

These people were loved, and their families haven’t stopped missing them.

Anthony DiMaria, 51, was only 3 when his uncle, Jay Sebring, was killed.

DiMaria remembers being about 4 and looking through a family photo album. He spotted an 8-by-10 photo of Sebring and asked his mother when he would get to see his uncle again. She told him that he wouldn’t.

“I saw something in my mother’s eyes that really shook me to the core, and that was to see my mother in a darkness and a pain that I don’t think very many children see their parent go through, especially their mother,” DiMaria said.

As a child, he tried to be proud of his uncle’s legacy. Jay Sebring is known for giving Doors frontman Jim Morrison his iconic look. His other customers included Frank Sinatra, Steve McQueen and Bruce Lee. He essentially created the men’s hair industry, DiMaria said.

But every time DiMaria would mention his uncle to friends, they’d ask where Jay Sebring was. When DiMaria was honest, when he mentioned Manson, his friends never knew what to say.

At 12, DiMaria was at a sleepover at a friend’s house, and they were watching “Saturday Night Live.” A sketch with Bill Murray came on in the middle of the episode.

Murray was part of an ensemble pitching a new rock musical, loosely inspired by the Manson killings. Murray was playing Jay Sebring.

At one point in the sketch, Murray sings about coming back to life so he can continue doing the hair of the female actress next to him. “I’m back with the living, and not dead,” Murray sang.

“I literally felt like vomiting,” DiMaria said. “I’m watching this, and my ears started ringing, and I thought, ‘Oh my God, my uncle’s life and his murder is a joke on my favorite TV show.’ ”

Over the past week, DiMaria has been asked whether Manson’s death brings his family a sense of closure.

“I can understand that question, but it doesn’t really have the awareness of what we deal with and the realities of these crimes,” DiMaria said. “Our family has definitely not derived any kind of comfort or closure from his passing, nor would we from any of the other killers, or any ill fate for the other inmates, but knowing that they will serve the rest of their lives behind bars, that’s the very least that they can do.”

‘I don’t want them glorified’

Originally, Manson and each of his followers were sentenced to die, but after the California Supreme Court abolished the death penalty in 1972, their sentences were reduced to life terms.

Today, Leslie Van Houten, 68; Patricia Krenwinkel, 69; Bobby Beausoleil, 70; Charles “Tex” Watson, 71; and Bruce Davis, 75; remain in prison. Susan Atkins, often dubbed the “scariest” of Manson’s female followers, died in 2009 at 61 after being diagnosed with brain cancer.

Each has been repeatedly denied parole, but in September, Van Houten was approved for parole by the state board. Gov. Jerry Brown, who has previously denied Van Houten parole, will ultimately decide whether she’s granted parole this time.

Over the past four decades, a group of family members -- Smaldino and DiMaria included -- have continued to attend the parole board hearings, advocating that Manson and his followers need to spend the rest of their days in prison.

The family members have gotten to know one another, and at times, represented one another before the board.

Debra Tate has spoken for the LaBiancas and many other family members at the hearings, attending so many of Manson and his followers’ parole board hearings that the state prison’s victim services department told her they’d actually lost count of how many hearings she’d been to.

Because of Debra’s sister’s fame, Sharon Tate has often received more media attention than the other victims. But Debra Tate has spoken out not only to honor and remember Sharon Tate, but also for the rest of the victims.

“I don’t feel anybody’s loss is greater than anyone else’s,” she said. “It’s horrible. It’s catastrophic. It’s completely debilitating, and the status that the loved one had in life has nothing to do with the depth of that loss.”

Debra Tate is a known victims’ rights advocate. Her mother, Doris Gwendolyn Tate, helped start the victims’ rights movement in California.

But that wasn’t always the Tates’ story. For the 10 years that followed Sharon Tate’s death, Debra Tate watched her mother struggle to navigate her grief.

In 1969, there were no trauma counselors to help families navigate their grief. There were no victims’ rights advocates to explain the court system. Instead, Debra Tate’s grieving mother suffered frequent breakdowns.

“She was a shell of a woman,” Debra Tate, 65, said. “She could function at times, and then, just break down completely in the next moment… My mother was a great woman on many levels, and it just broke my heart. I didn’t know what to do for her , and consequently didn’t know what to do for myself.”

Then came a phone call from Stephen Kay, a Los Angeles County deputy district attorney who helped prosecute the Manson cases.

He told Debra’s mother that one of her daughter’s killers was up for parole.

“Gwennie, they’ve got 600 [support] letters,” Kay told her. “Do you think you can do better than that?”

This was the moment when Debra Tate saw the spark return to her mother’s eyes.

By standing on street corners and in front of supermarkets and bars, by telling their story in the media, the Tate family gathered thousands of signatures against the inmate’s release. Doris Gwendolyn Tate went on to advocate for legislation that would help crime victims.

Today, Debra Tate receives phone calls at all hours of the night from violent-crime victims, seeking relief from their pain and resources to navigate the system.

“It makes me feel as it did my mother, that there is some kind of good that can come out of all this ugliness,” Debra Tate said. “By helping someone else recognize and be able to process their pain, you’re actually helping yourself.”

Kay Hinman Martley, 80, said getting to know Debra Tate and the others has made her trips from Colorado to California to advocate for her late cousin, Gary Hinman, more manageable because they have a shared experience.

However, each time she speaks to the parole board, it feels more difficult to persuade them that her cousin’s killers should stay behind bars. The story never changes -- Gary is gone, and his killers have admitted to what they did, she said.

She listens as attorneys discuss what the Manson followers have done while behind bars, earning college degrees and living as model inmates. But for Martley, that’s irrelevant.

She thinks back to the cousin whom she used to listen to play classical music on the piano every Sunday afternoon, her family gathered around Gary to listen.

“I don’t really care what they do [in prison],” Martley said. “I don’t care what the state makes them do. I don’t care -- but I don’t want them out, and I don’t want them glorified.”

jaclyn.cosgrove@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.