A wiretap brings privilege and helicopter parenting to the fore in the college admissions scandal

Gordon Caplan had a problem. Last year his teenage daughter was slogging her way through a series of practice ACTs. But her scores were unlikely to get her to where he believed she should be: a high school senior with a clutch of acceptance letters.

She needed a higher score.

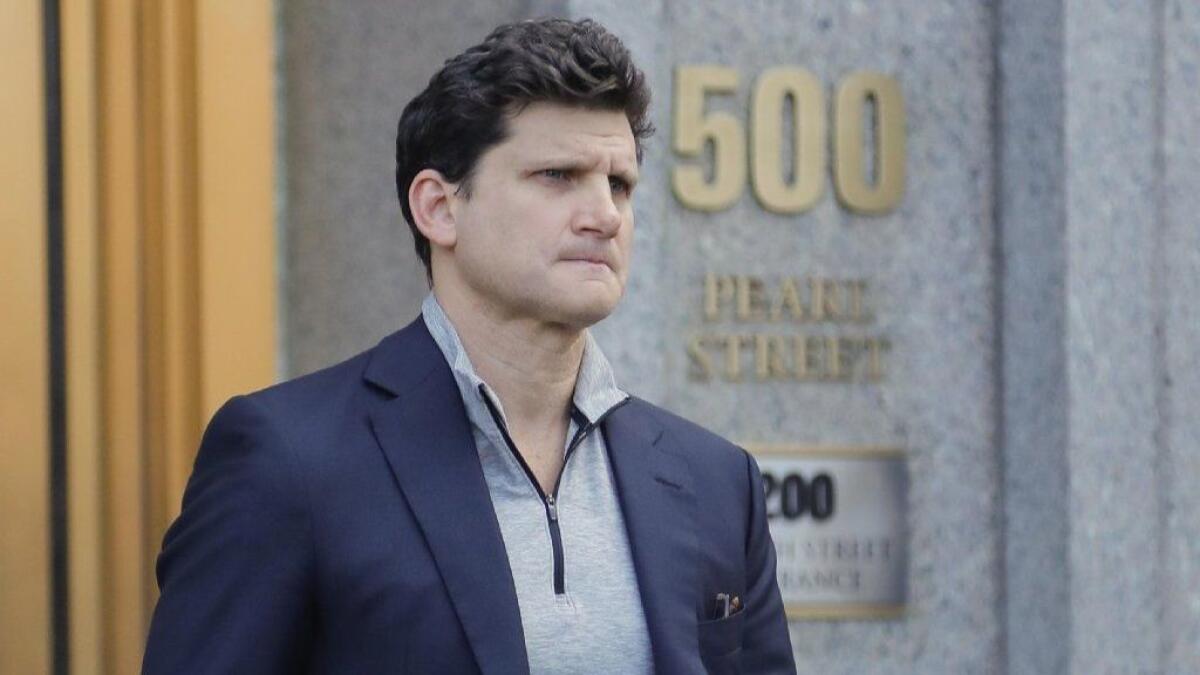

Caplan, a high-powered lawyer from Greenwich, Conn., and his wife began talking with William “Rick” Singer, the admitted mastermind of the college admissions scandal that continues to dominate a national conversation about privilege and parenting.

According to transcripts of wiretapped conversations that were released by federal prosecutors when charges against 50 people — including Singer and Caplan — were announced, Caplan was concerned that his daughter might find out about the ruse.

“To be honest, I’m not worried about the moral issue here,” Caplan said. He was worried about discovery.

“If she’s caught doing that, you know, she’s finished.”

The Newport Beach admissions consultant told his client that their silence was key to achieving the desired outcome. Authorities say that Caplan, who declined to comment through his attorneys, then signed off on a $75,000 payment, which was masked as a donation to Singer’s foundation.

Wealthy parents have been going to great lengths to help their kids get into elite universities for years. But this well-documented — and viral — moment in the helicopter-parenting era indicates a willingness to go to greater extremes.

In an era of badly behaving bankers, entertainment and sports figures, and government officials who tweet first and think later, the cheating may seem like perversely logical behavior.

But experts in parenting say the win-at-all-costs attitude can have a pernicious effect on a child. When they try to clear the way for their children’s success, parents are essentially saying to their kids that they can’t do it on their own, a stance that may block the path to successful adulthood.

In an effort to ensure that his son was admitted to the Jimmy Iovine and Andre Young Academy at USC, Bill McGlashan allegedly paid Singer $250,000 to, among other things, fabricate a football career. Although McGlashan’s son’s high school didn’t have a football team, his son was suddenly a kicker. Authorities say the new addition to his list of achievements partially came thanks to Photoshop.

McGlashan, who founded and was fired last week from the private equity investment firm TPG Growth, had been called “one of Silicon Valley’s most prominent voices for ethical investing.”

According to the transcripts, McGlashan asked Singer, “Is there a way to do it in a way that he doesn’t know that happened?”

Singer told him that his son would know only that Singer was “going to get him some help.”

“That [networking] he would have no issue with,” McGlashan is quoted saying to Singer. “You lobbying for him.”

“No issue.”

But a slew of people who regularly interact with and study the behavior of frantic parents overwhelmingly disagree.

This kind of behavior can breed a helplessness in children who never face adversity or failure. That, in turn, can lead to increased anxiety and depression, said author and teacher Jessica Lahey, who regularly writes about parenting and is the author of a book titled “The Gift of Failure.”

Lahey recounted a recent visit to a college where she met the mother of a 20-year-old with diabetes. The mom still tracks her daughter’s blood sugar via a computer app and says she has no plans to stop. That’s an indication, Lahey said, the mother doesn’t think her daughter is capable of doing this seemingly basic task on her own.

“When we do too much for our kids, and we tell them what to do every step of the way, they never build up a tolerance for frustration,” she said. “The problem is that kids who can’t be frustrated don’t learn as well.”

Dr. Kenneth Ginsburg, the co-director at the Center for Parent and Teen Communication at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, says parents should be more focused on planning for what their kid will be like at age 35 rather than thinking just about where they’ll be at 18. A single-minded focus on short-term achievement at any cost can lead to all sorts of emotional distress for children, he said.

“When we think of the 35-year-old we’re raising, we begin to think about the importance of self-confidence, honesty and integrity,” he said. “If we communicate to them that it’s all about what’s good for you, we’re undermining the adults we’re raising.”

As this scandal plays out, there’s no denying the notion that getting into a good school may be more important than ever, according to Northwestern University economist Matthias Doepke. In his latest book, “Love, Money and Parenting: How Economics Explains the Way We Raise Our Kids.” Doepke and his coauthor Yale Professor Fabrizio Zilibotti, emphasize economics in an effort to understand aggressive parental behavior.

“We have found in our research that varying parenting styles among nations are rooted primarily in economics — specifically, economic inequality,” they wrote in the Washington Post weeks before this scandal broke. “The common denominator in countries where intense, achievement-oriented parenting abounds is a large gap between the rich and the poor.”

Doepke said that the stakes are especially high for parents who are in the top .1% of earners and undoubtedly know the gap between what a college graduate and a non-college graduate earns has grown substantially.

“It’s not that surprising that at the top of society, there’s an anxiety that your kids won’t stay in this [economic] position,” Doepke said.

Ted Dorsey, who runs a large test-prep agency in Los Angeles, works both with the offspring of billionaires and students who are undocumented immigrants. His clients are all looking for an edge, but the most extreme instances of parents diving into their kids’ academic lives stem from a certain amount of vanity.

Recently, he said, one of his clients got a less than satisfactory result on a practice SAT. The student’s mother made her disappointment known, pointing to a series of college flags in Dorsey’s office and announcing, “You won’t get in there. You won’t get in there.”

“They’re so status-driven,” Dorsey said.

“They’re in these social groups, and they orient themselves around brand-name recognition.”

The current state of affairs has been decades in the making. In the last 40 years, the amount of time American parents spend interacting with their kids has doubled, but all that togetherness has not coincided with a burst of confidence on the part of parents and children.

One of the solutions, Doepke said, is not to tell helicopter parents to chill out, but to take steps to curb inequality in a system that tends to benefit the people who are already well off. That could come in the form of more vocational training, free early-childhood education and more parity in funding for public schools.

Dorsey’s solution is more intimate: For a parent, “the best way to be there is be supportive and kind, and give kids love and confidence, and the bad way to do it is cheat behind their back.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.