As San Francisco rents soar, tenants still willing to pay for earthquake safety

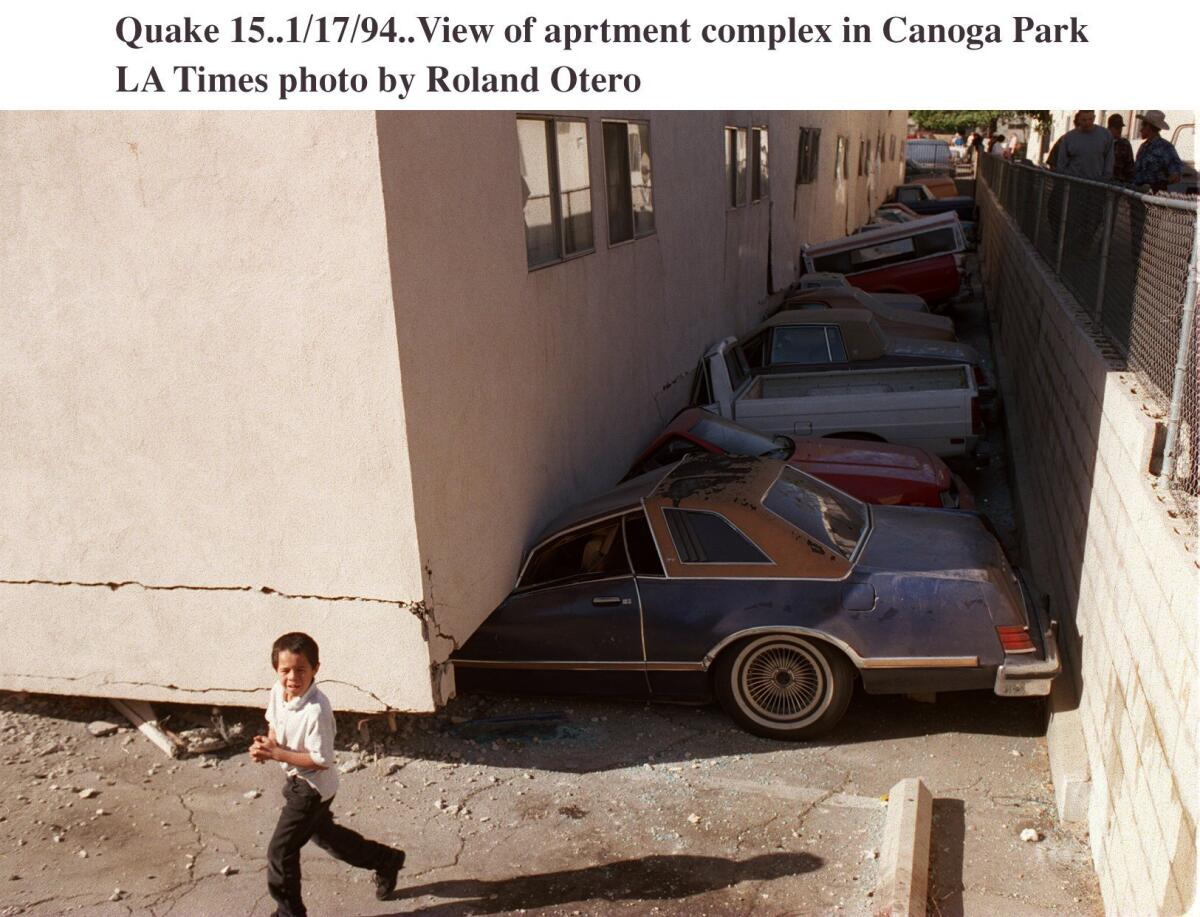

The upper stories of an apartment building in Canoga Park collapsed onto the ground floor in the 1994 Northridge earthquake.

The rental market here was already under siege when city officials began an ambitious earthquake retrofitting project whose costs will largely be passed on to renters.

Fueled by the city's tech boom, rents have soared, with average one-bedroom units going for $3,500 a month. Low-income tenants are being evicted as a large number of apartments are being taken off the long-term rental market to be turned into condos or leased to users of Airbnb and other short-stay leasing services.

But the anger over the situation hasn't extended to the earthquake-retrofitting law, even though the $60,000- to $130,000-per-building price tag will be largely paid for through rent increases over the next two decades.

Renter advocates say the costs are an added burden. But they acknowledge that in return, tenants will get something essential - protection from a type of building that has collapsed and killed residents in California's last two major earthquakes.

"We are in the middle of an earthquake zone, and tenants deserve the certainty of safety when a natural disaster hits," said Sara Shortt, executive director of the Housing Rights Committee of San Francisco.

The reaction in San Francisco is instructive as a Los Angeles City Council committee Wednesday considers an even more ambitious retrofit law.

Los Angeles' law would require as many as 13,500 quake-vulnerable wood-frame apartments to be strengthened, compared to 5,000 in San Francisco.

The law proposed by Mayor Eric Garcetti would also mandate retrofits of as many as 1,500 brittle concrete buildings, a problem San Francisco has not yet addressed.

If passed, Los Angeles' law would be the most sweeping seismic safety measure passed in California history.

Graphic: Why can these wood apartments collapse in earthquakes?

Graphics by Raoul Rañoa / Los Angeles Times

The cost to renters has emerged as a big political issue. While not as bad as San Francisco, Los Angeles is one of the most unaffordable cities in the nation for tenants, where the average one-bedroom rent is nearly $2,100, according to Real Answers, a rental research firm.

Existing law allows Los Angeles to follow San Francisco's lead and allow owners to pass on all costs of mandatory earthquake retrofits to tenants through a rent increase of as much as $75 a month.

But after much study, Los Angeles housing officials proposed a 50-50 split — owners and renters would each pay half the costs, with a rent increase capped at $38 per month. (By contrast, rents in San Francisco can go up 10% every year until the tenant is paying the full cost.)

See the most-read stories this hour >>

City officials are also looking for other ways to help. Garcetti supports state legislation that would allow owners to apply for a tax break equal to 30% of the retrofit costs. The bill, AB 428, passed the state Legislature in September but needs Gov. Jerry Brown's signature. Owners have also sought more financial aid, like a reduction in property taxes and expensive building-permit fees.

The skinny, flimsy columns above the carport in this El Centro, Calif., apartment building leave the structure unstable after the Easter Sunday earthquake hit Baja California in 2010. (Fred Turner / California Seismic Safety Commission)

Renter advocates in L.A. remain concerned about how much tenants will have to pay, and said they will fight the retrofitting law if the financial arrangements aren't fair.

"While we do support making these units safe, it can't be on the backs of those least able to pay," said Larry Gross, executive director of the Coalition for Economic Survival.

Costs have long been the big barrier to requiring owners to act. But over time, mandatory retrofitting has taken hold in a few cities.

Mother Hyun Sook Lee and her son, Jason Lee, comfort each other at the graveside during a funeral for her husband, Pil Soon Lee, 47, and son Hawon Lee, 14, killed in the collapse of the Northridge Meadows apartment complex. Many of the 16 who died in the collapse suffocated from intense body compression from the weight of the destroyed building.

Hyun Sook Lee and her son, Jason Lee, comfort each other during a funeral for her husband, Pil Soon Lee, 47, and son Hawon Lee, 14, killed in the collapse of the Northridge Meadows apartment complex. (Gerald Burkhart / Los Angeles Times)

The Silicon Valley suburb of Fremont was one of the first cities in California to make a big push in retrofitting wood-frame apartments. Sixteen years later, there's only one building left to upgrade, said Jeff Schwob, the city's community development director.

Berkeley began slapping more than 320 quake-vulnerable buildings with warning signs in 2005, and instructed owners to tell tenants that their apartments could pose "a severe threat to life safety."

More than 100 were retrofitted voluntarily, and Berkeley then ordered the remaining buildings to be retrofitted.

"So much of Berkeley is controversial, but this one kind of really went through without a whole lot of opposition," said Eric Angstadt, the city's planning and development department director. "I think everybody generally thinks it's a good idea to have seismic retrofits for these types of buildings."

Graphic: There's a flaw in apartments on top of carports, supported by skinny, flimsy columns.

The threat of wooden apartment buildings has been known for years; collapses killed at least three people in San Francisco during the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake and 16 people in an apartment building in the 1994 Northridge earthquake.

Backers of retrofitting told tenants that rent increases are a small price to pay. A major quake in San Francisco, they said, would destroy many apartments that would be replaced by new dwellings not covered under rent control.

For owners, retrofits will protect against costly lawsuits if a collapsed building injures or kills people, and keep rent checks flowing after a quake strikes.

"It's work that needs to be done," said Janan New, executive director of the San Francisco Apartment Assn.

Fixing the problem: Add steel frames to ground story.

Some owners have quickly moved to begin retrofits. Since San Francisco passed a mandatory retrofit law in 2013, owners of more than 270 buildings have finished retrofits for 5,058 vulnerable structures across the city, years ahead of deadlines to complete construction.

Owners of more than 660 other buildings have applied for or received building permits for retrofit construction.

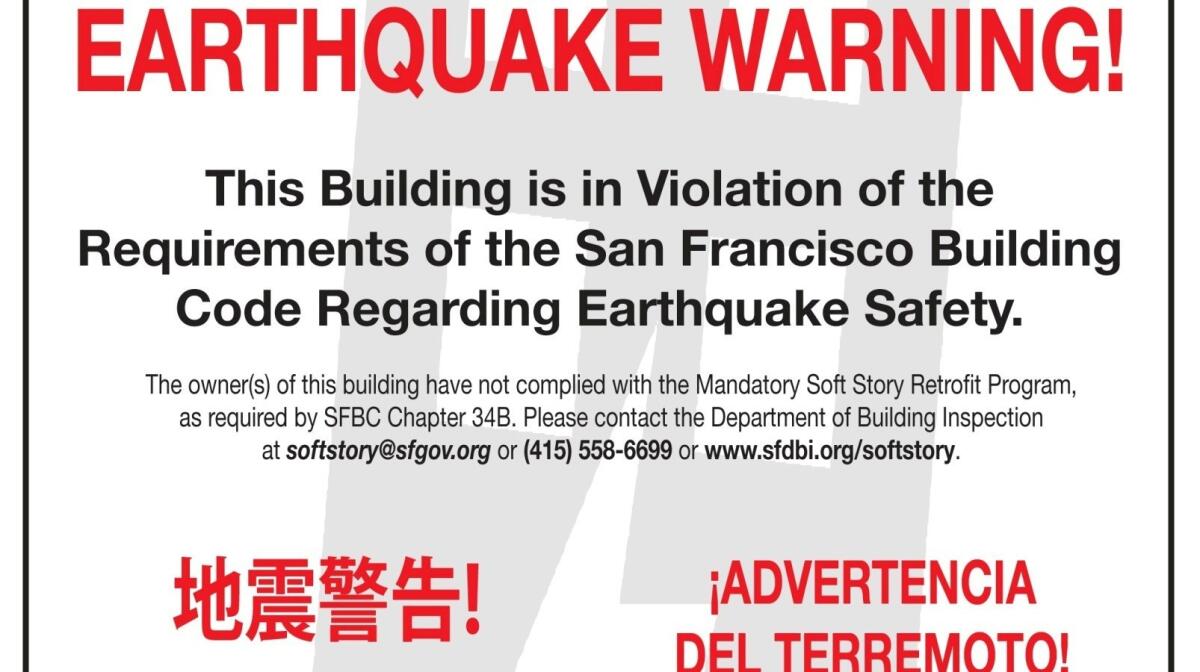

So far, most building owners have complied with the mandatory retrofit deadlines. Owners who miss deadlines have had provocative signs posted on their buildings by city officials that say "Earthquake warning!" in large red letters, set over an image of a collapsing building.

A section of the placard posted on buildings in San Francisco out of compliance with the mandatory retrofit law.

Last year, more than 400 buildings were marked with the warning signs after missing a deadline to turn in a retrofit screening form. As of last week, only three remain.

"It was amazing. It worked really fast," said Patrick Otellini, who heads San Francisco's earthquake safety program. These signs "actually said something to tenants that live in these buildings."

Neither owners nor tenants were thrilled initially at the prospect of retrofits. After opposition, city officials made it easier for low-income residents to request an exemption from the retrofit rent hike.

Seismic retrofits are now seen as a regular cost of business. "As a landlord ... you have a responsibility to make sure you're housing people in a safe place," Otellini said.

Retrofitting a building was considered optional and too costly in the past, but now, "it's almost becoming politically incorrect to talk about earthquake safety in that way," Otellini said.

A building crushed a car in San Francisco's Marina District in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. (Adam Teitelbaum / AFP/Getty Images)

Some owners who have completed retrofits have already received approval for rent hikes. In one nine-unit building in the Sunset District, the San Francisco Rent Board approved a monthly rent increase of about $62 to cover the expenses of a $99,000 retrofit and interest.

If the Los Angeles housing committee passes the legislation Wednesday, it could be considered by the full City Council as early as Friday.

Some Los Angeles renter and owner groups have objections to the legislation, including a concern that four years is too little time to get wooden apartments retrofitted.

The mayor said there should be no delays.

"Every month we wait is a month that the Big One could hit," Garcetti said. "And we would look back and say, if we had just done this a little more swiftly, lives and properties would've been saved."

Graphics illustration by Raoul Rañoa. Reporting by Rong-Gong Lin II and Rosanna Xia. Graphic sources: Structural engineer David Cocke; Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Follow us on Twitter for more earthquake safety news: @ronlin @RosannaXia @ranoa

Update, 9:41 p.m.: This article was edited throughout, and adds more information about perspectives from Los Angeles tenant and owner groups, and when the legislation could be considered by the full Los Angeles City Council. This article was originally published at 6 a.m.

MORE ON EARTHQUAKES:

30 years after Mexico City quake, hundreds still live in temporary camps

Statewide tax credits for seismic retrofitting face a hurdle on Gov. Brown's desk

L.A. officials present a plan for renters and landlords to split the costs of quake retrofitting

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.