San Diego — They’ve been hiding in storage for 90 years: rare, never-before-published photographic images of Charles Lindbergh on his way to becoming Charles Lindbergh.

It’s April 28, 1927. In three weeks, Lindbergh would make the first nonstop airplane flight across the Atlantic Ocean, 3,610 miles in 33 hours from New York to Paris. The feat won a $25,000 prize and turned him into one of the most famous and admired people on Earth.

But on this day, he was in San Diego, a little-known mail pilot with an experimental plane he called the Spirit of St. Louis. It had been custom-built here by Ryan Airlines in just 60 days. Lindbergh, 25, climbed into the tiny cockpit and prepared to fly the wood, cloth and metal contraption for the very first time.

1/32

04.28.1927 — Charles A. Lindbergh’s initial test flight of the Spirit of St. Louis, which Ryan Aircraft built in San Diego. The dirt airfield is Dutch Flats, where the Midway post office once stood.(Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 2/32

March 1, 1927 — Charles A. Lindbergh in front of a Ryan Aircraft monoplane in San Diego. (Photo by Stanley Andrews Jr. / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Stanley Andrews Jr. / The San Diego Union-Tribune) 3/32

04.28.1927 — Charles A. Lindbergh’s test flight of the Spirit of St. Louis, which Ryan Aircraft built in San Diego. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 4/32

04.28.1927 — Charles A. Lindbergh’s test flight of the Spirit of St. Louis, which Ryan Aircraft built in San Diego. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 5/32

04.28.1927 — John van der Linde, chief mechanic at Ryan Aircraft, turns the propeller over for the first engine run during Charles A. Lindbergh’s initial test flight of the Spirit of St. Louis. Ryan Aircraft built the plane in San Diego. The dirt airfield is Dutch Flats, where the Midway post office once stood. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 6/32

04.28.1927 — Charles A. Lindbergh’s test flight of the Spirit of St. Louis, which Ryan Aircraft built in San Diego. The dirt airfield is Dutch Flats, where the Midway post office once stood. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 7/32

04.28.1927 — Charles A. Lindbergh’s test flight of the Spirit of St. Louis, which Ryan Aircraft built in San Diego. The dirt airfield is Dutch Flats, where the Midway post office once stood. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 8/32

04.28.1927 — Charles A. Lindbergh taking off on his initial test flight of the Spirit of St. Louis in San Diego. The New York-to-Paris monoplane was built by Ryan Aircraft in San Diego and was completed in just two months. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 9/32

04.28.1927 — Charles A. Lindbergh’s initial test flight of the Spirit of St. Louis, which Ryan Aircraft built in San Diego. The dirt airfield is Dutch Flats, where the Midway post office once stood. Mission Hills can be seen in the background. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 10/32

04.28.1927 — Charles A. Lindbergh’s initial test flight of the Spirit of St. Louis, which Ryan Aircraft built in San Diego. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 11/32

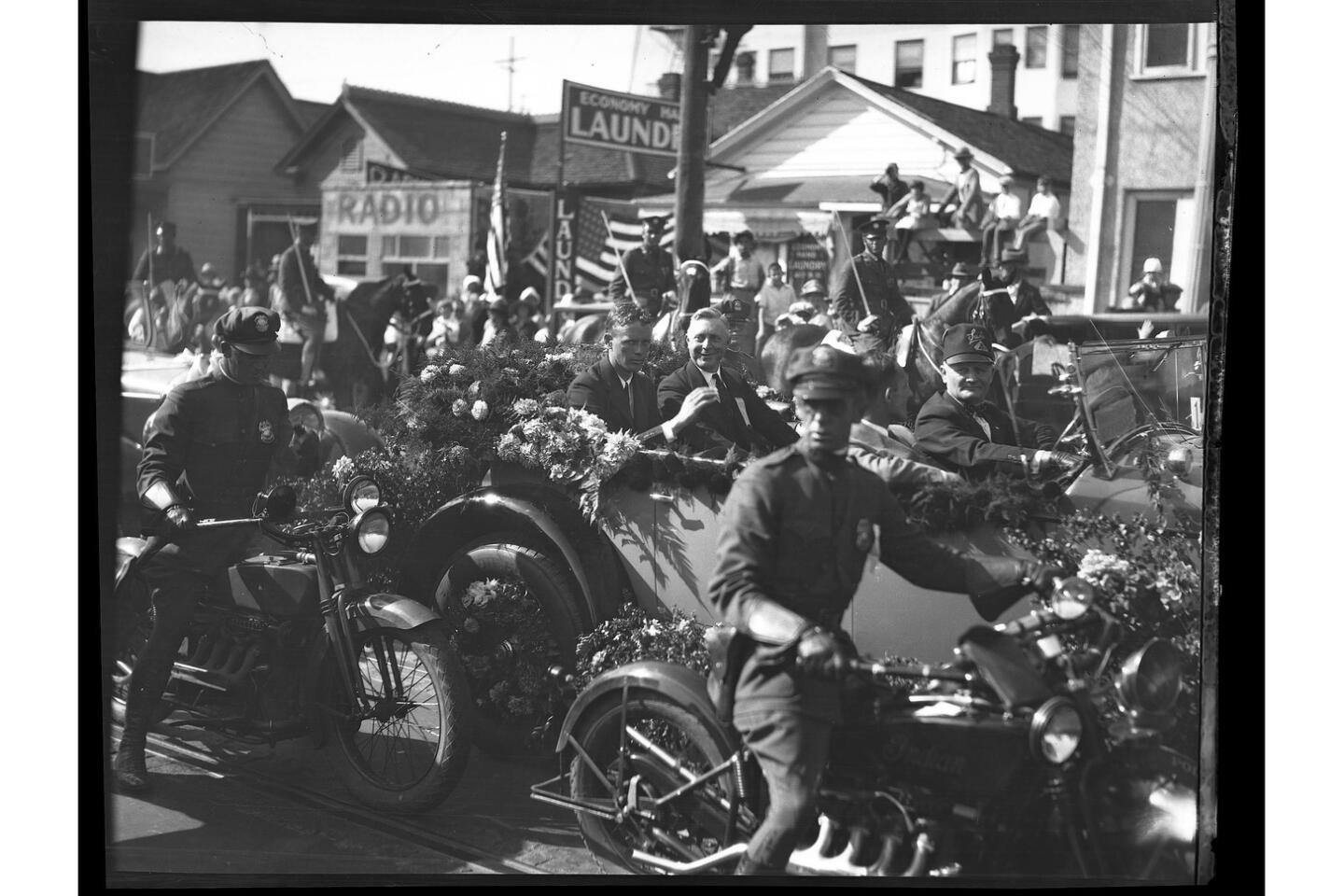

09.21.1927 — Charles A. Lindbergh rides with San Diego Mayor Harry C. Clark during a parade to welcome him back to San Diego after his New York-to-Paris flight. Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 12/32

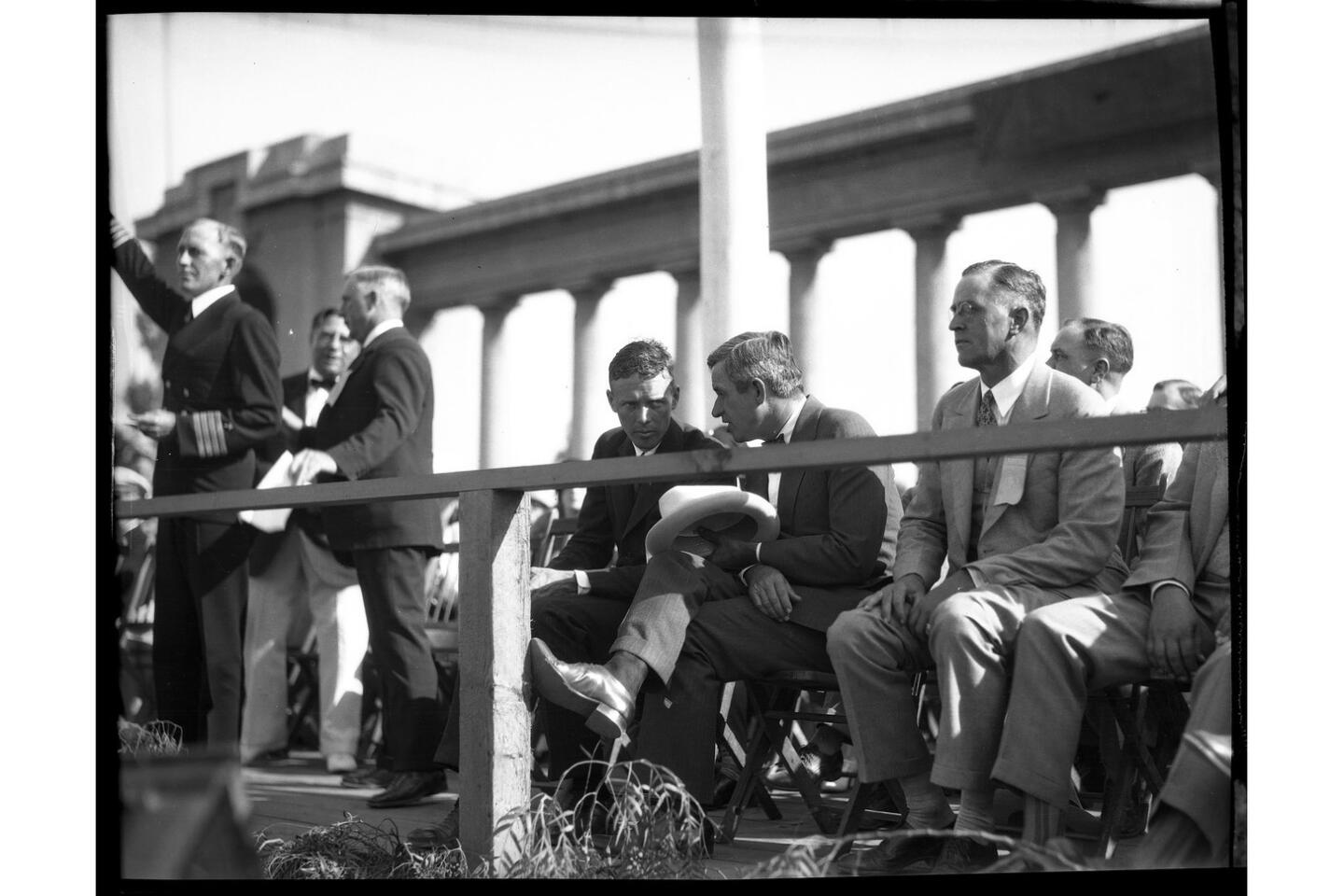

09.21.1927 — Charles A. Lindbergh during his welcome back to San Diego celebration. Sitting next to him is humorist Will Rogers. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 13/32

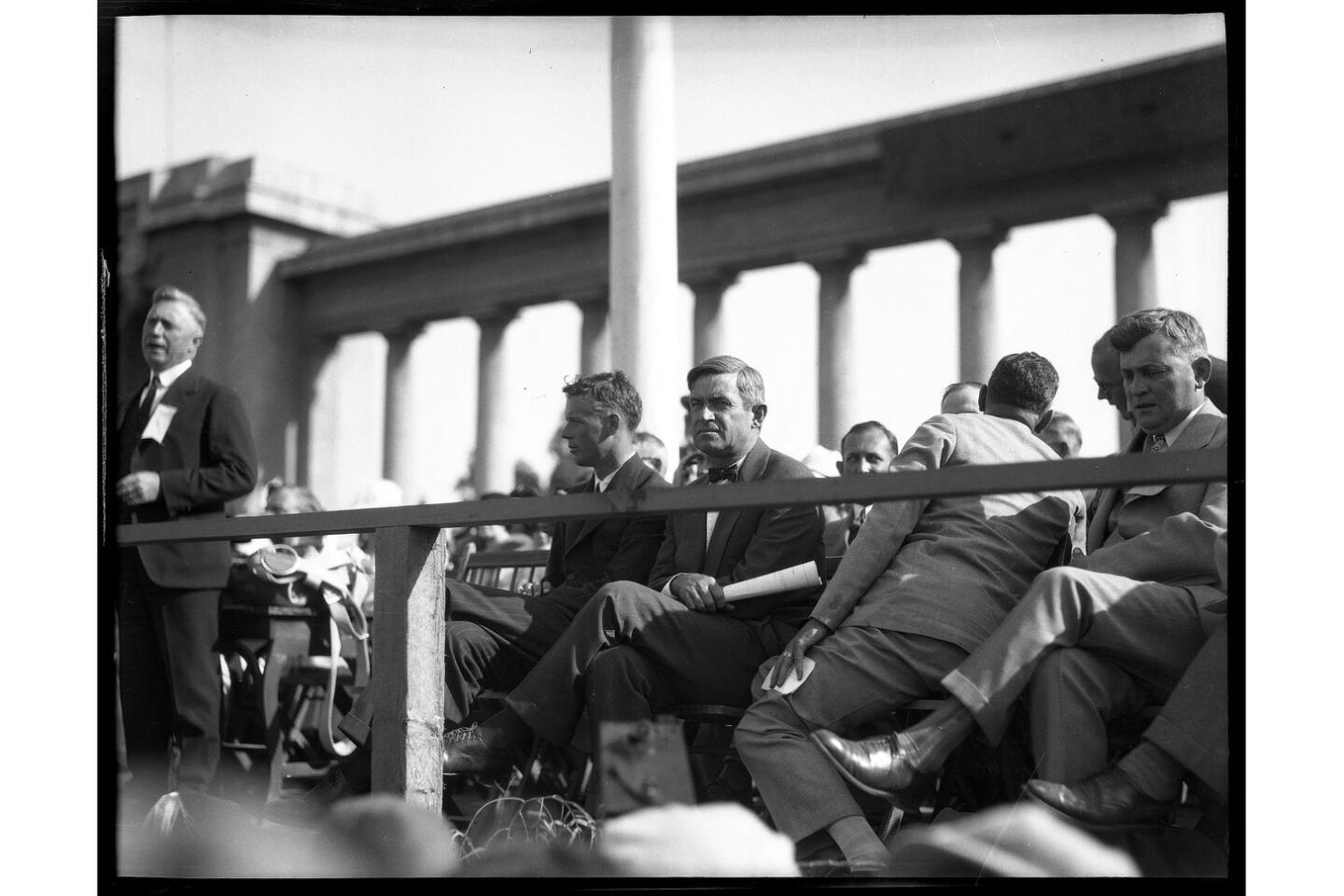

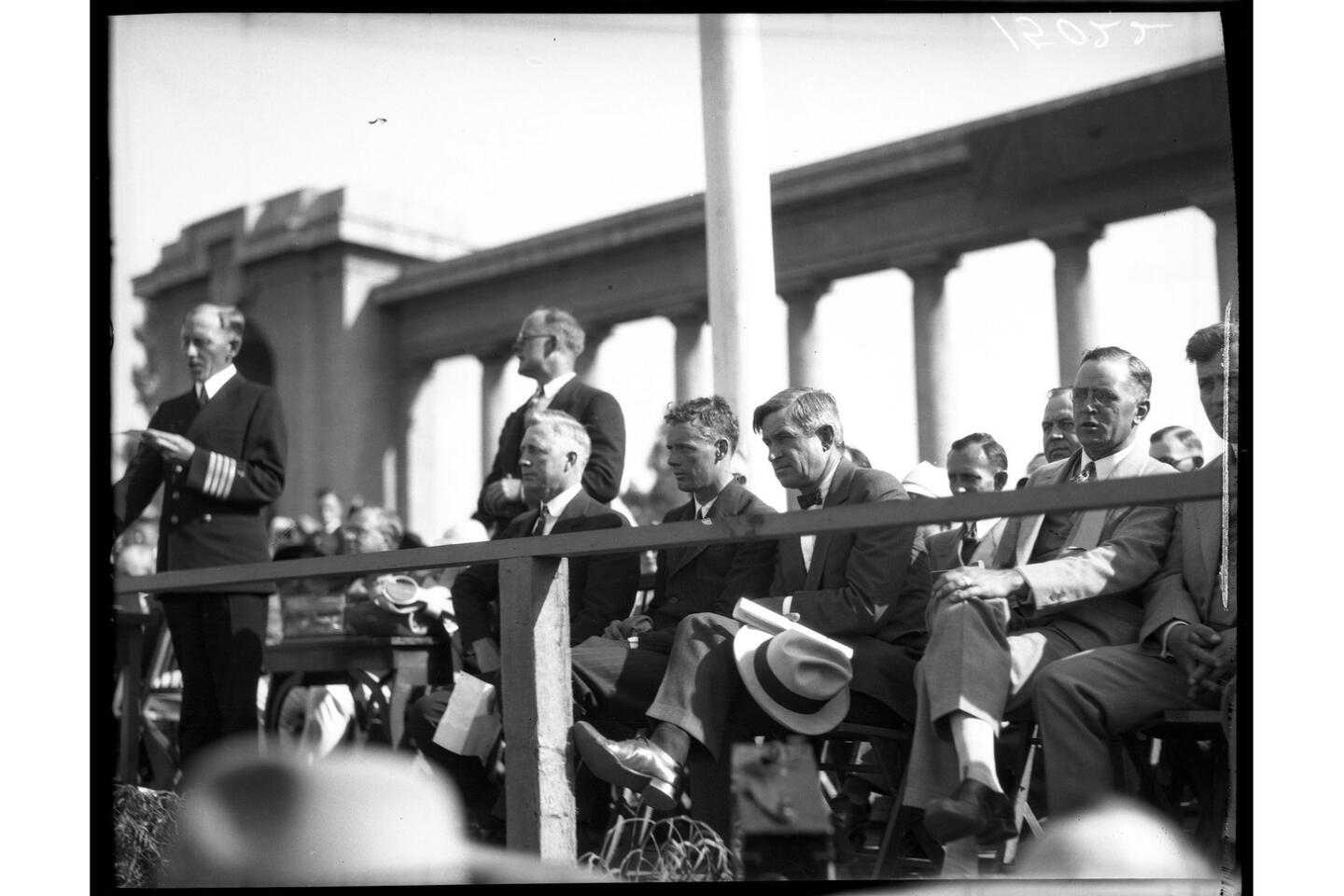

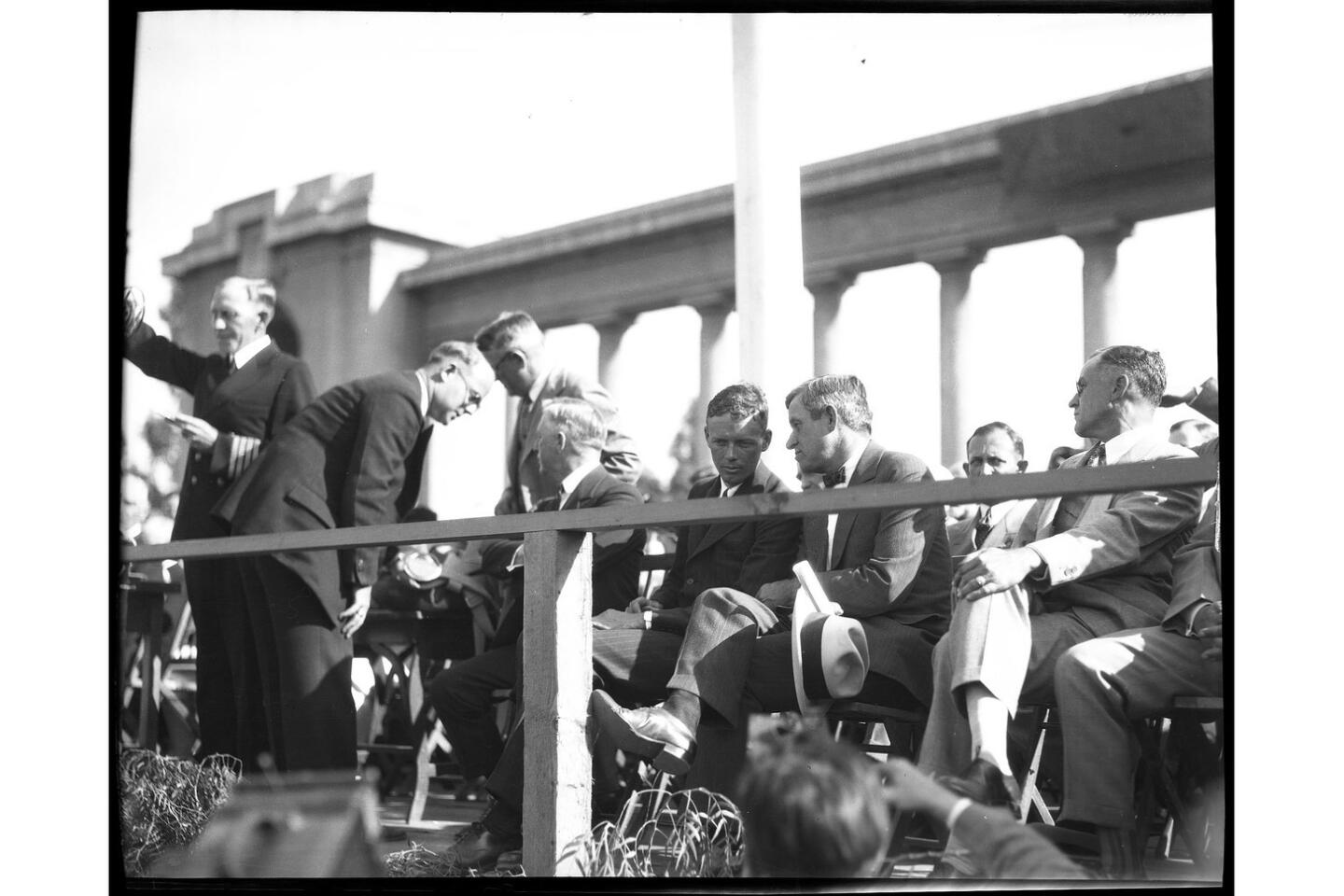

09.21.1927 — R.D. Workman, chaplain of the 11th Naval District, delivered the invocation at ceremonies in Balboa Stadium to welcome Charles Lindbergh back to San Diego. Seated, from left, are Mayor Harry C. Clark, Lindbergh, Will Rogers and Jack Lyman. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 14/32

09.21.1927 — Charles A. Lindbergh addressed the crowd during his welcome back to San Diego celebration at Balboa Stadium. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 15/32

09.22.1927 — The Spirit of St. Louis, which Ryan Aircraft built in San Diego. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 16/32

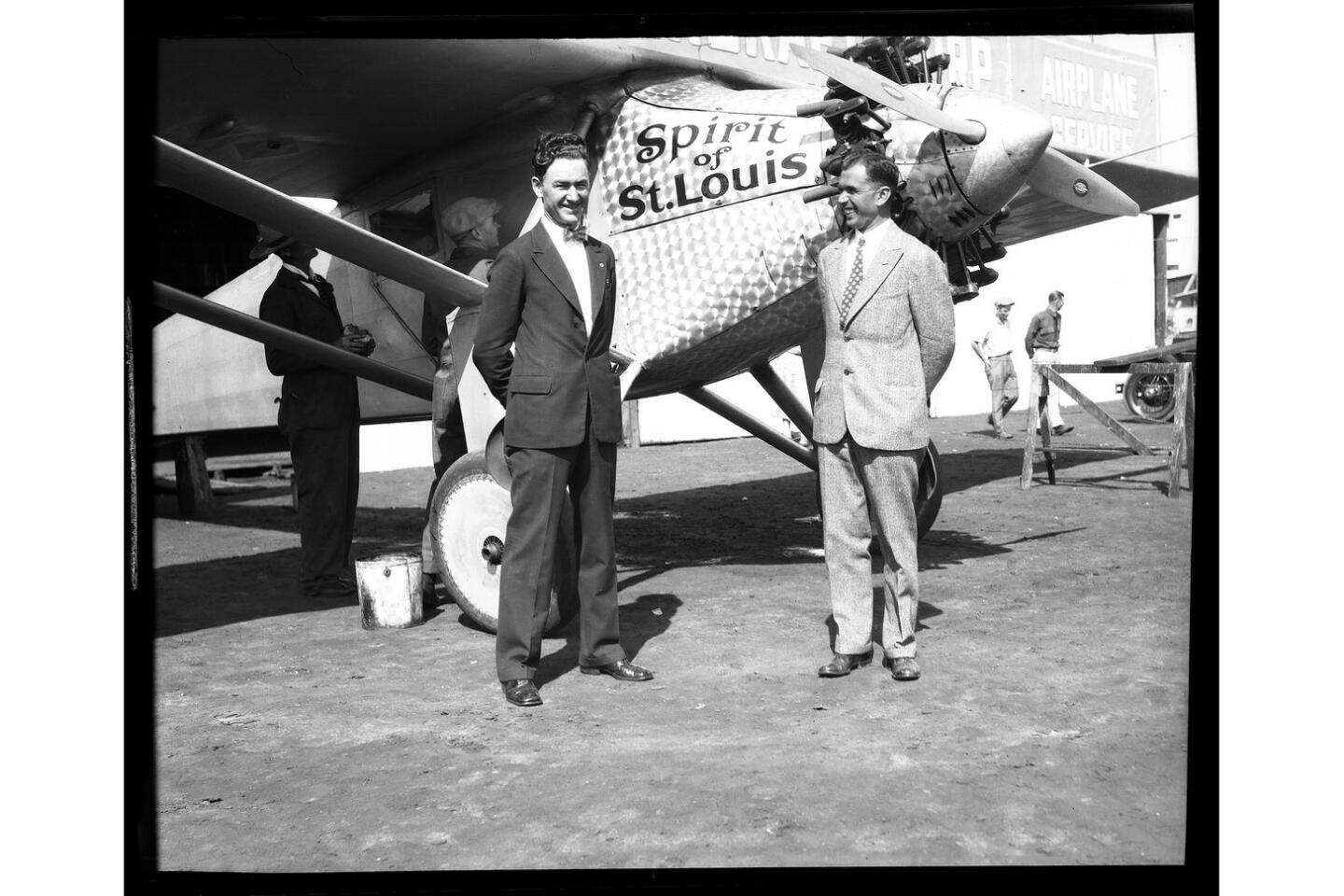

09.22.1927 — Unidentified men pose with the Spirit of St. Louis, which Ryan Aircraft built in San Diego (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 17/32

09.22.1927 — Three Boy Scouts stand in front of the Spirit of St. Louis. From left to right are F. Novelo, A. Ondarza and E. Lopez. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 18/32

09.21.1927 — From left, R.D. Workman, chaplain of the 11th Naval District, Mayor Harry C. Clark, and seated, Charles A. Lindbergh, humorist Will Rogers and Jack Lyman, during ceremonies at Balboa Stadium to welcome Lindbergh back to San Diego. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 19/32

09.21.1927 — Charles A. Lindbergh, in front of the microphone, addresses the crowd at Balboa Stadium when he returned to San Diego after his historic New York-to-Paris flight. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 20/32

09.21.1927 — Charles A. Lindbergh addresses the crowd at Balboa Stadium when he returned to San Diego after his historic New York-to-Paris flight. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 21/32

09.21.1927 — Charles A. Lindbergh is seated next to humorist Will Rogers during ceremonies at Balboa Stadium to welcome him back to San Diego after his historic New York-to-Paris flight. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 22/32

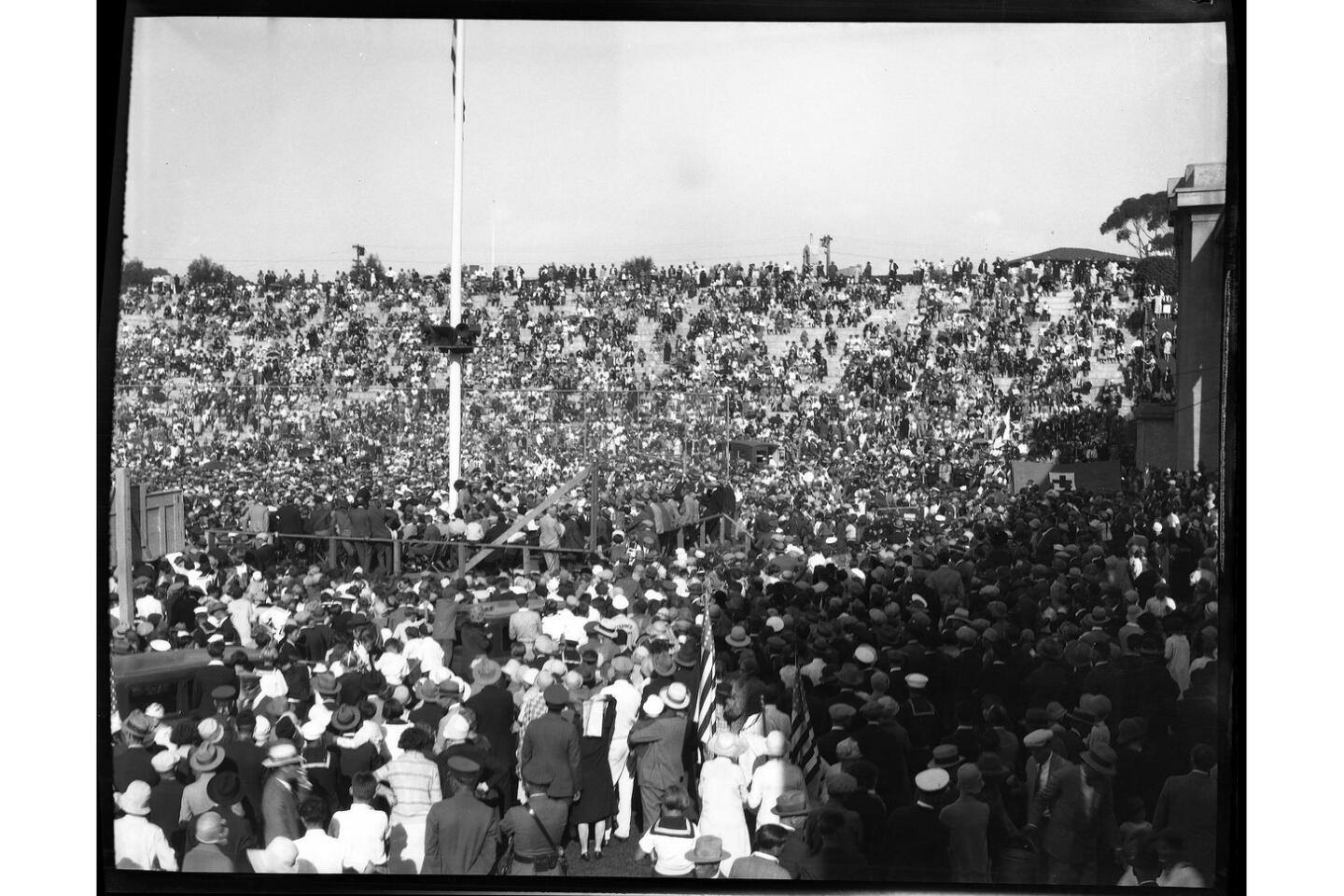

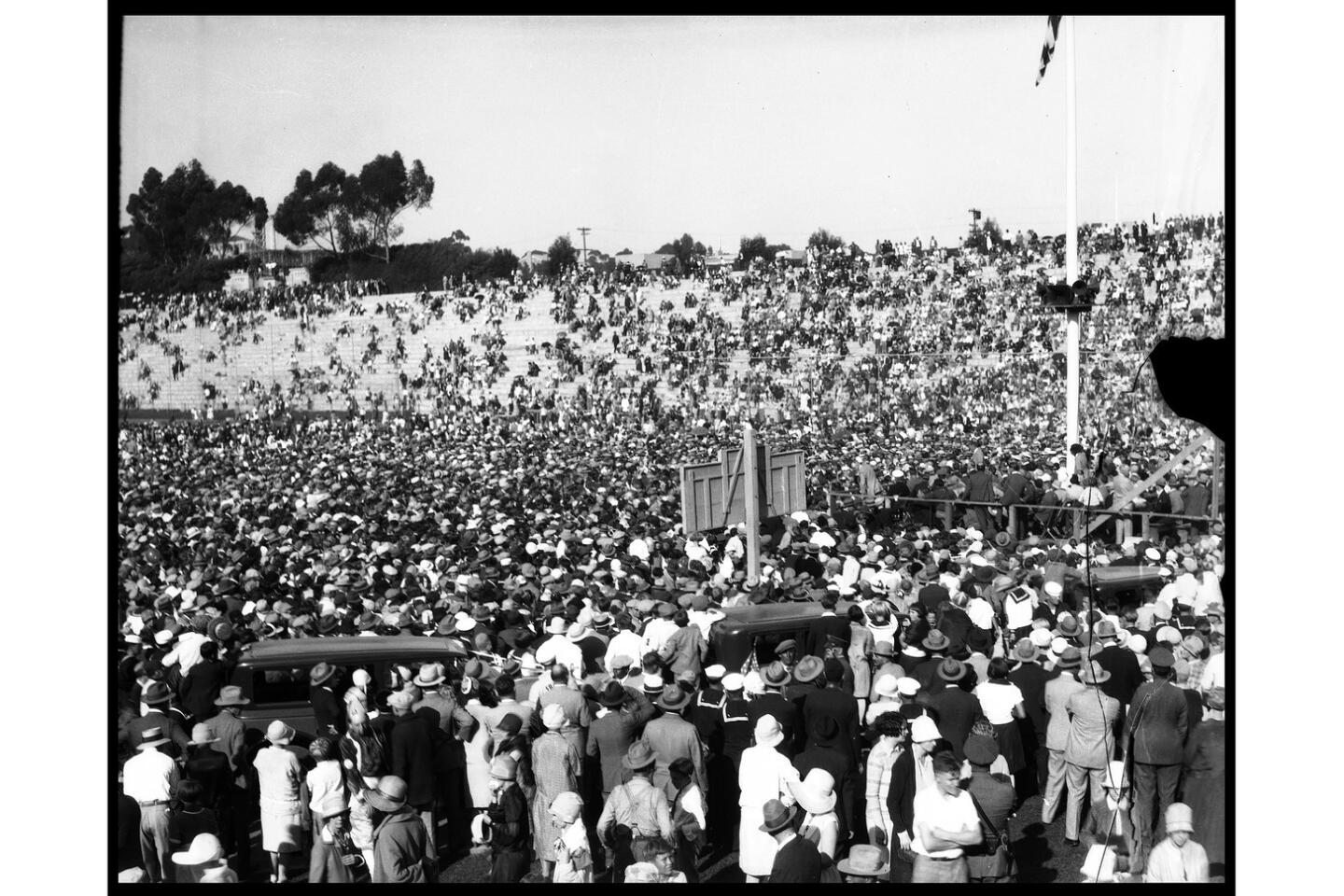

09.21.1927 — A crowd of 60,000 people jammed Balboa Stadium to welcome Charles A. Lindbergh back to San Diego after his historic New York-to-Paris flight. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 23/32

09.21.1927 — Charles A. Lindbergh rides with San Diego Mayor Harry C. Clark in a car during a celebration welcoming him back to the city after his historic New York-to-Paris flight. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 24/32

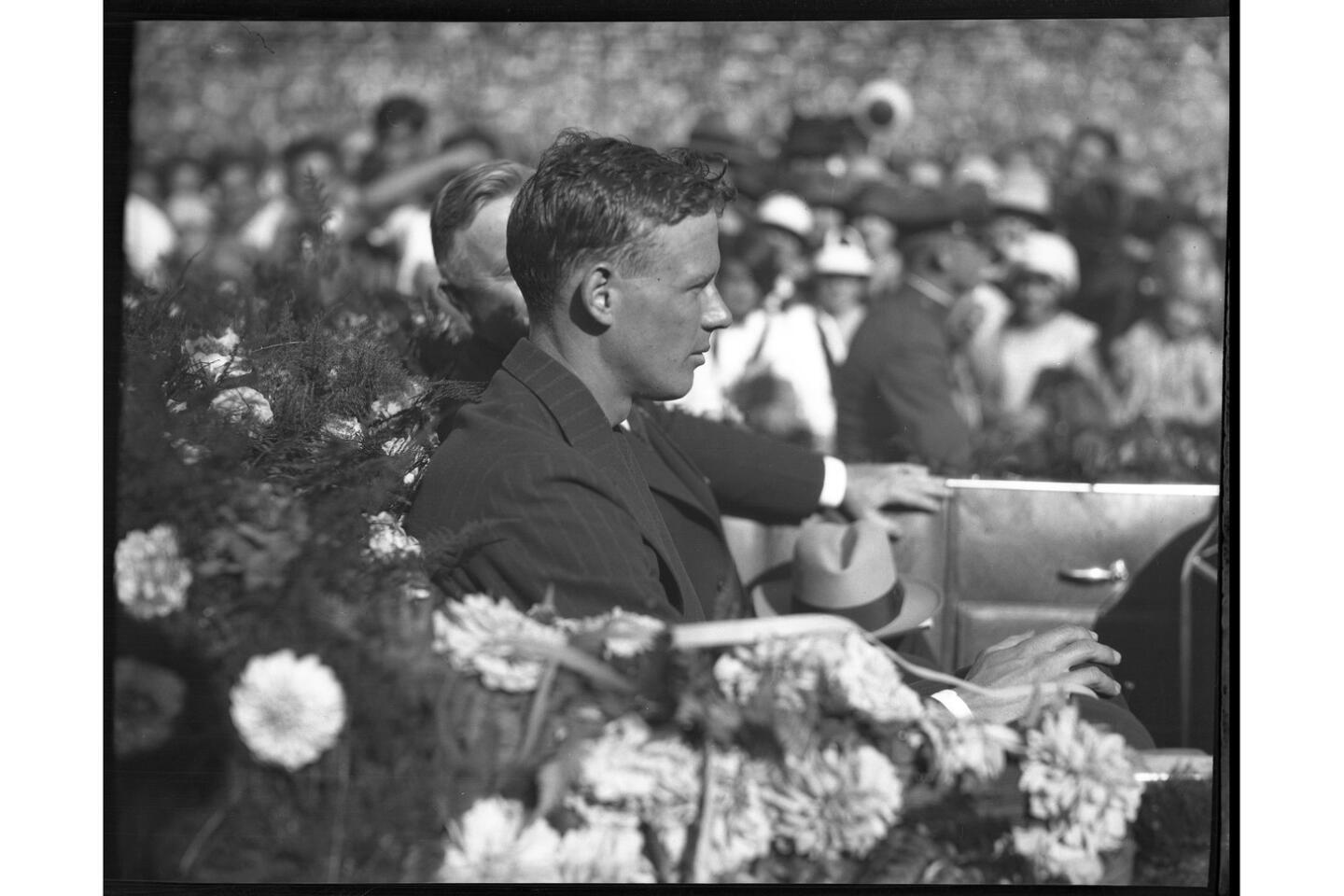

09.21.1927 — Charles A. Lindbergh rides in a car during a celebration to welcome him back to San Diego after his historic New York-to-Paris flight. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 25/32

09.22.1927 — A crowd of 60,000 people jammed into Balboa Stadium to welcome Charles A. Lindbergh back to San Diego four months after his historic solo nonstop flight across the Atlantic. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 26/32

09.21.1927 — The Spirit of St. Louis was built by Ryan Aircraft in San Diego. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 27/32

09.21.1927 — B.F. Franklin Mahoney of Ryan Aircraft was the first to greet Charles A. Lindbergh when the Spirit of St. Louis rolled to a stop at the Ryan Airfield in San Diego. Ryan Aircraft built the plane. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 28/32

09.21.1927 — Charles A. Lindbergh rides with San Diego Mayor Harry C. Clark in a flower-bedecked car during a celebration to welcome him back to San Diego after his historic New York-to-Paris flight. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 29/32

09.21.1927 — A crowd that included some of the men who built the Spirit of St. Louis gathered to greet Charles A. Lindbergh when he landed at the Ryan Airfield in San Diego four months after his historic New York-to-Paris flight. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 30/32

09.22.1927 — Charles A. Lindbergh inspects the Prudden all-metal monoplane with G.K. Prudden in the cockpit with him. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 31/32

09.22.1927 — Luncheon at the Mahoney plant in San Diego to celebrate Charles A. Lindbergh’s historic New York-to-Paris flight. To the left of Lindbergh are B.F. Mahoney and A.J. Edwards. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) 32/32

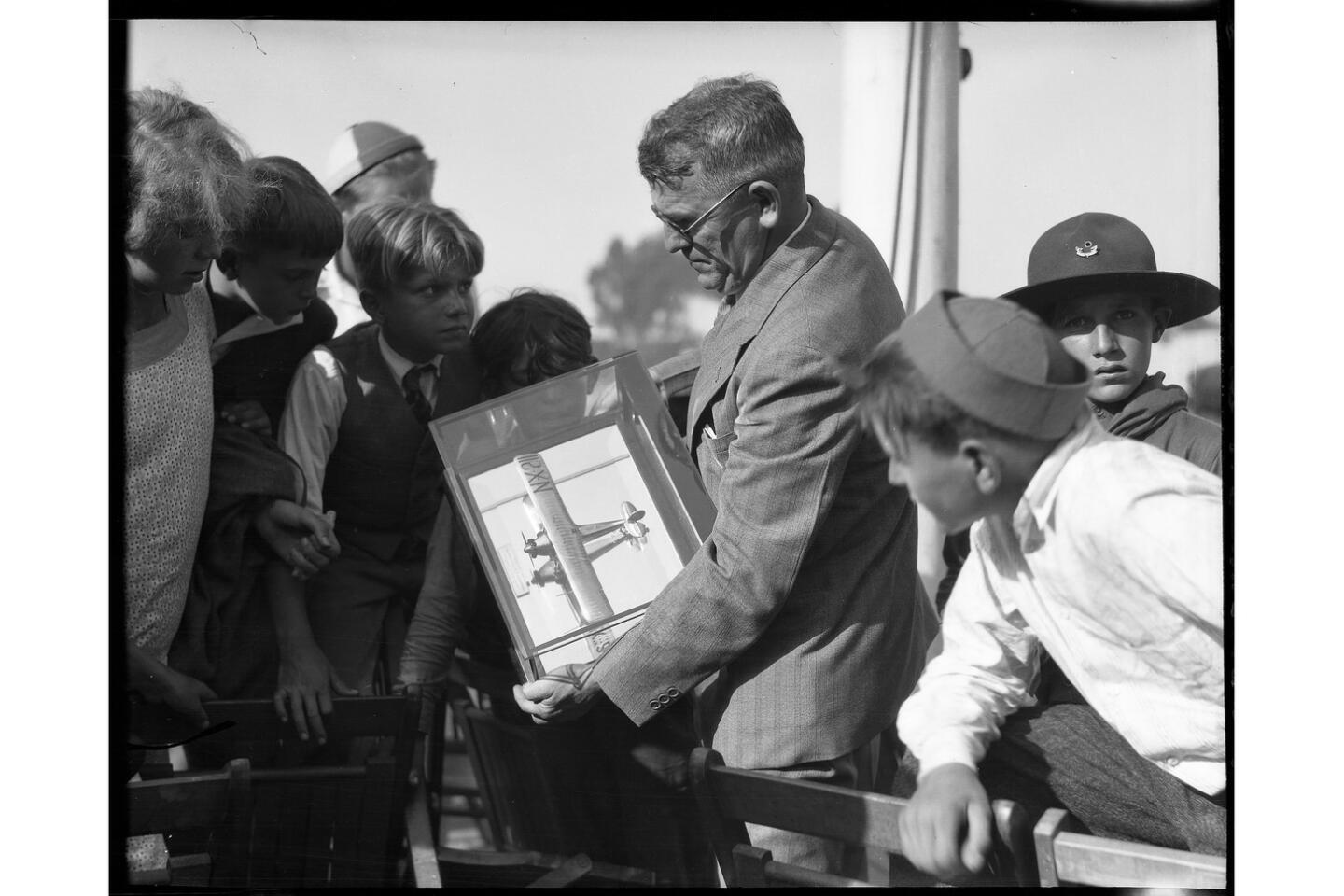

09.21.1927 — Alonzo Jessop holds a silver replica of the Spirit of St. Louis, built to scale, which was presented to Charles A. Lindbergh at Balboa Stadium as a reminder of his “ship” and San Diego, the city where it was built. (Photo by Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune)

(Harry T. Bishop / San Diego Union-Tribune) “What a beautiful machine it is, resting there on the field in front of the hangar, trim and slender, gleaming in its silver coat,” Lindbergh would later write. “All our ideas, all our calculations, all our hopes lie there before me, waiting to undergo the acid test of flight. For me, it seems to contain the whole future of aviation.”

He was at a dirt airfield called Dutch Flats, where the Midway Post Office would one day be built. Some Ryan employees were there to watch. And so was Harry Bishop, chief photographer for the San Diego Union and Evening Tribune.

One of Bishop’s images — the plane coming in for a landing, Mission Hills in the background — ran on the front page of the next day’s Union. The accompanying story said that the monoplane flew “with the speed and grace of a sparrow” and that Lindbergh was pleased with the 30-minute tryout.

Bishop took at least eight other photos that day, and it appears that only one of them — of the plane at rest — may have been published. Among the unseen others, one picture shows a crew member grabbing for the propeller to start the engine. One shows the plane in a steep climb. Two show people running toward the plane after it lands.

“They’re terrific photos,” said Robert van der Linden, a curator at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., where Lindbergh’s plane is one of the main attractions. “I’ve only seen one or two others taken at Dutch Flats [during the first test flight], so these help bring what happened there to life. It’s exciting to see them.”

Mark Aldrich, a longtime volunteer archivist at the San Diego Air & Space Museum in Balboa Park, said the pictures are “a before-view of magic about to happen,” likening them to “the instant before Armstrong steps on the moon, the second before the flag was raised by U.S. Marines on Mt. Suribachi, the calm in the field as Lincoln ascended the stage to read the Gettysburg Address.”

After the test flight, Lindbergh stayed in San Diego, working with Ryan designer Donald Hall on modifications to the plane. He flew it almost two dozen more times, checking the speed, the handling, the weight of heavy fuel loads. On May 10, 1927, shortly before 4 p.m., he took off from North Island and flew overnight to St. Louis. A day later, he flew on to New York.

And then into history.

A year ago, as the Union-Tribune was moving from its longtime offices in Mission Valley to downtown San Diego, researcher Merrie Monteagudo boxed up files of photographs, some 90,000 images that date to the late 1890s.

She found one labeled “Lindbergh negatives.” That struck her as unusual because most of the newspaper company’s negatives had been donated years ago to the San Diego History Center.

Inside the file, there were four images, portraits of Lindbergh and B.F. Mahoney, owner of Ryan Airlines, shot by Union photographer Stanley Andrews Jr. in March 1927. The other 4- by 5-inch pictures were in an envelope that had “Lindbergh, Charles A.” and “ ‘Spirit of St. Louis’ monoplane” typewritten on it. It also was marked “4-28-27,” the day of the first test flight.

Looking through the photos, Monteagudo said she was struck by how they dovetailed with the descriptions of the first flight that Lindbergh included in “The Spirit of St. Louis,” his 1953 memoir.

“He talks about how gleaming the machine is, and there’s a picture of it,” she said. “He talks about how he accelerated, and there’s a picture of that too. It’s almost like he’s narrating a slideshow.”

The envelope holding the negatives also had the typewritten initials “HTB” on it, for photographer Harry T. Bishop, who joined the newspaper in 1921. The photographer already had a fascination with aviation — having taken aerial photographs of the city from a hot-air balloon — so it wasn’t surprising he wound up taking the pictures of Lindbergh’s first test flight six years later.

In September 1927, four months after his famous trans-Atlantic flight, Lindbergh returned to San Diego, a hero for the ages. Everything was different now — for him, for the future of aviation, for the world.

Bishop again was on hand to take photos. Lindbergh circled the Ryan plant a couple of times in his plane. He rode in a parade to Balboa Stadium, where 60,000 people — the largest crowd in city history to that point — waited to see him. Schools were closed.

Joaquin Ortiz, director of innovation at the Museum of Photographic Arts in Balboa Park, said he was drawn to “the sense of urgency” in the Lindbergh photos. “They tell us a story we wouldn’t otherwise see,” he said.

Part of that story is San Diego. “You can see Mission Hills in the background, see the factories,” Ortiz said. “It’s a chance for us to reflect on who we were, and who we are today.”

He added, “People know about Lindbergh’s famous flight, but many of us don’t realize the plane was built in San Diego. These images bring that to life in a way that text doesn’t.”

By the end of 1927, voters in San Diego had passed a bond issue to pay for construction of an airport. It would be called Lindbergh Field.

Wilkens writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

john.wilkens@sduniontribune.com