Artists, college students, music lovers lost to the Oakland warehouse fire

Em Bohlka was a poet with a master’s degree in literature who could quote Kurt Vonnegut. Donna Kellogg played the drums and inspired peers with her culinary skills. Feral Pines was a recent Oakland arrival, a bass guitarist, a good listener.

They were artists with day jobs, young creatives living off the grid, students dreaming of unconventional paths — at least 36, all taken by fire.

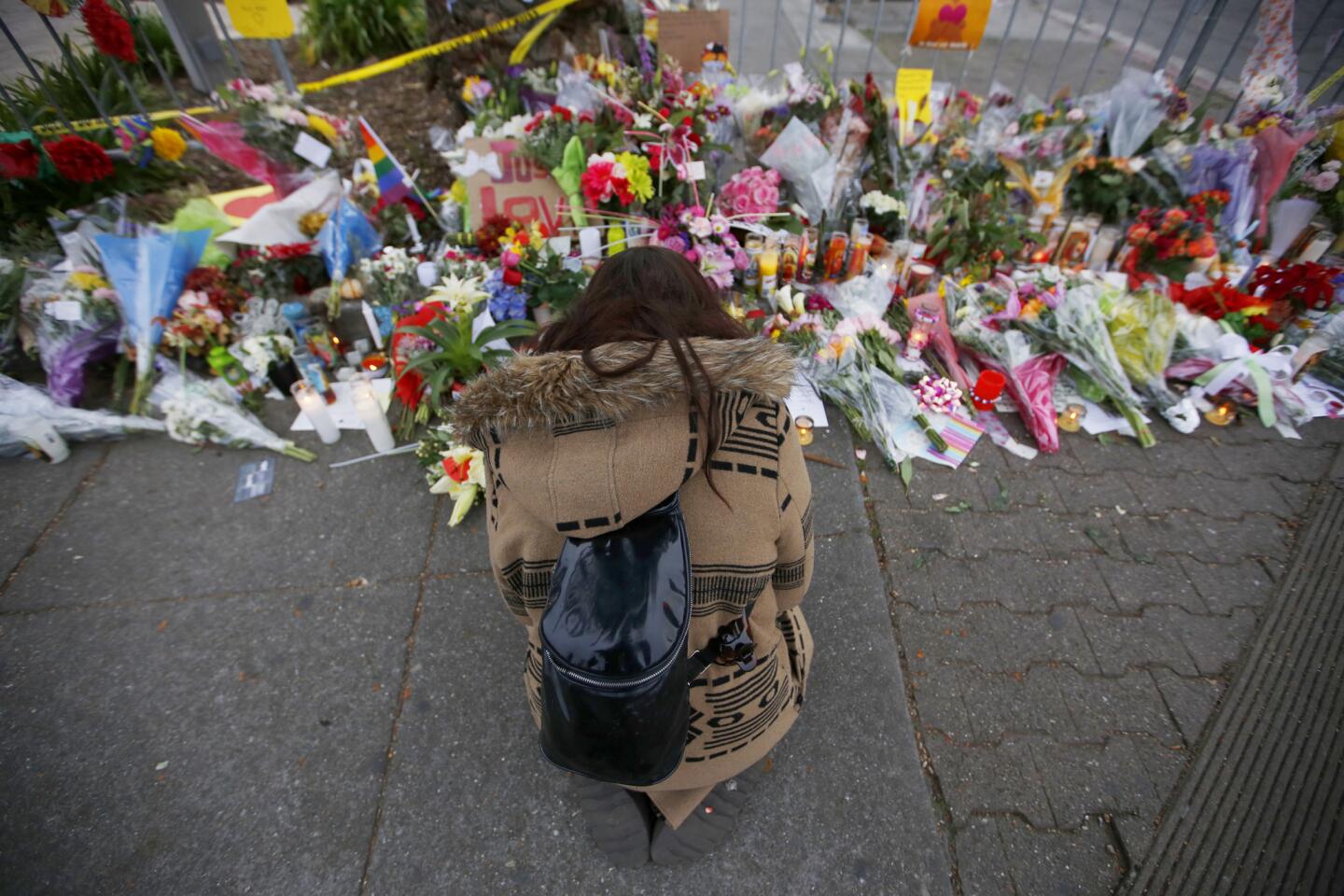

On Monday their names were scrawled on notes left at memorials that bloomed where flames had ravaged an Oakland warehouse. “Travis, we already miss you.” “Thinking of you, Ara Jo.” “Draven, you weren’t the smartest or the funniest or the bravest. That’s probably why we were best friends.”

Once a bastion of hippies and independent artists, the Bay Area in recent years has been dominated by techies and those with deep pockets who can afford the outrageous rents.

But the Oakland fire ripped through a close-knit community of artists ensconced in an underground music scene and committed to staying in the area. Their makeshift homes, their counterculture social scene, existed in a world invisible to those not searching for it.

It was where they felt accepted and safe.

“It’s an interesting group of people that all come together around the craft of electronic music and digital art,” said Josette Melchor, founder of a San Francisco-based arts nonprofit, who knew many of the victims.

“People have been doing this for decades and have been part of this community for so long. We’re not just talking about a rave, it’s really a group of close people that see each other almost every weekend, just kind of gathering around the creation of their own music.”

Melchor’s organization, Gray Area Foundation for the Arts, was inundated with calls after the fire from people looking for any way to help. In response, it established a fund for the families of victims, which had reached more than $300,000 by Monday night.

They had gathered Friday at a concert whose location, until the last minute, remained a mystery. Then came the name on social media, shortly before the doors opened: the Ghost Ship warehouse in Oakland.

Cash Askew had looked forward to what was to be a gathering of like-minded artists and musicians, many of them “queer femmes.”

A transgender woman, Askew had grown up around independent musicians and it was no surprise when she began to perform. The 22-year-old played in the goth-pop duo Them Are Us Too, which recently released its first LP and had been on tour.

“Everybody just saw this star, just saw this shooting star in her,” said Madigan Shive, a fellow musician who had known Askew for more than a decade.

Askew was accustomed to alternative venues. They felt protected, judgment-free.

“We came to those places and those spaces to share music that was often looked at as strange or esoteric,” said Askew’s girlfriend, Anya Taylor, a performance artist. “A lot of us are people who know music and we’ve been outcast because of who we are. We were making music for us.”

When Askew headed to the Ghost Ship, Taylor stayed behind because of work the next day. “Have fun,” she said. “Be safe.”

News of the fire sent the 23-year-old rushing to the warehouse, where flames had overtaken the building. For four hours, Taylor stood outside.

“I watched the building burn, and I lost the love of my life,” she said.

In some ways, identification of the dead has been better than not yet knowing.

When Jack Bohlka heard how devastating the fire had been, he worried he wouldn’t know for days. Police appeared at his Claremont home at dawn Monday. His child, Em, 33, was gone.

Earlier this year she had transitioned. She felt renewed. Her father couldn’t have been more proud.

“She was just a completely loving individual, truly a gentle spirit, thoughtful and philosophical,” Bohlka, 62, said.

The fire brought the community out into the light. Bohlka said he hopes it stays there.

“To let them know that they’re all loved,” he said, his voice breaking. “And they should truly be who they want to be.”

His daughter had worked as a barista, writing poetry and practicing photography from time to time. She and her father shared a love for “Slaughterhouse-Five” and texted Vonnegut quotes to each other. One they loved: “Out on the edge you can see all kinds of things you can’t see from the center.”

Unusual venues like the Ghost Ship are where those on the margins floated into the mainstream. Such artist-friendly spaces are few, some say, and need to be preserved.

They fear backlash could lead to evictions or the closure of other locations — which would be an affront to the victims:

Chelsea Faith Dolan, who took the stage in neon outfits and dramatic eye makeup to perform her brand of electronic music. Barrett Clark, a sound engineer and mainstay at shows, known for his patience and warmth. Travis Hough, 35, a school creative arts therapist who sang and played synthesizer in an electronica band.

Jennifer Kiyomi Tanouye had worked in music for years, at indie record stores, booking live acts, most recently as a music manager at Shazam. At a company-wide meeting Monday, employees celebrated her energy and kindness, which had made her an artist favorite.

“She walked quietly in her unassuming way, sprinkling us with her brilliance and creativity, opening our eyes to a better world,” her aunt Cheryl Tanouye said.

For those waiting to hear official word about a loved one, there is no memorializing, only dread.

Alex Vega, 22, remained missing Monday. His girlfriend, Michela Gregory, has been confirmed among the dead.

Vega, a San Bruno resident who worked at a funeral parlor, liked to host parties with underground musicians and was always up for the odd event like a midnight concert on the beach.

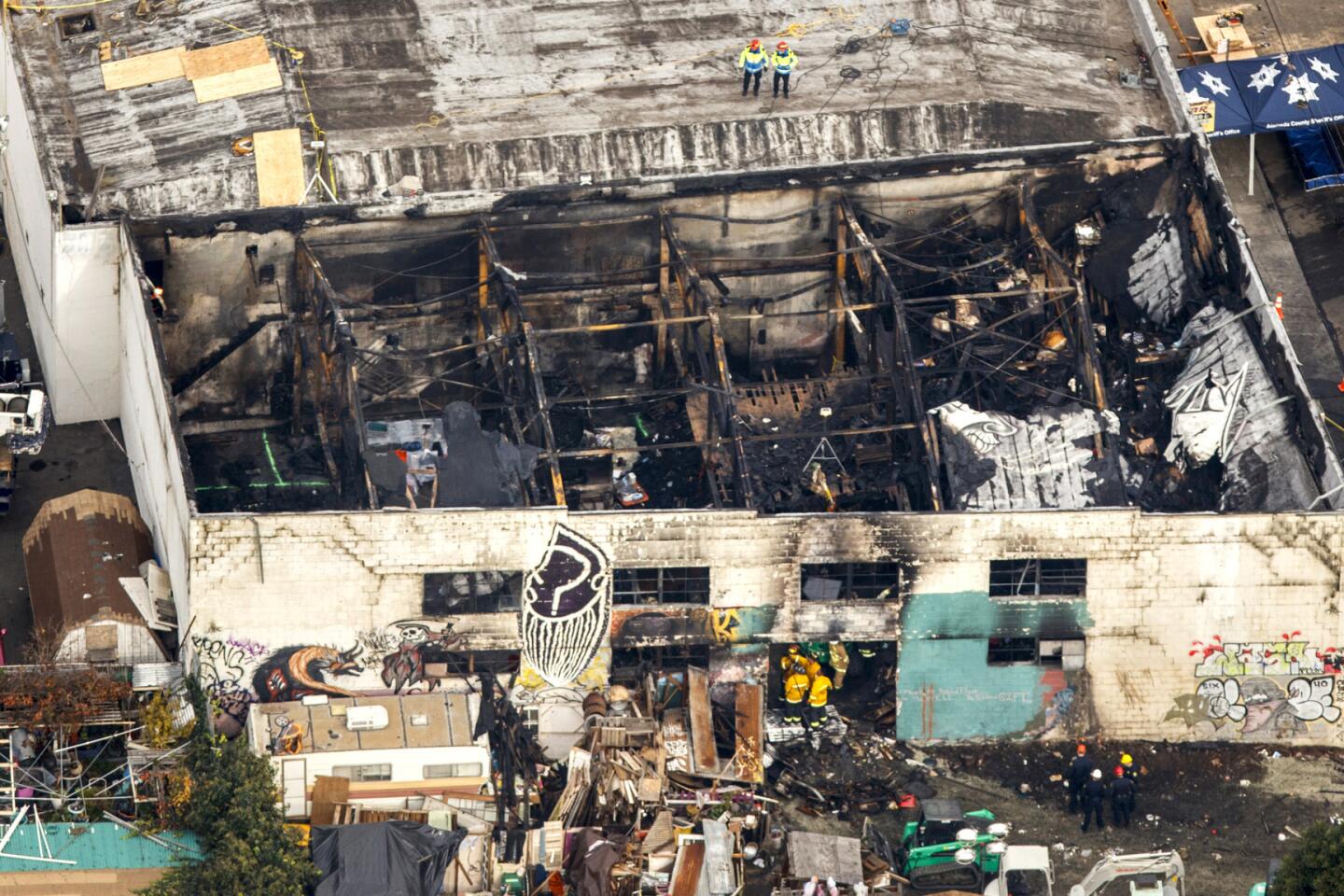

His older brother, Alberto Vega, arrived Monday at the Ghost Ship, now a blackened shell. With hands shoved into his sweatshirt pockets, he peered past the caution-tape barrier.

“I don’t know what I’m doing,” he said, glancing at a fence blanketed with photos and posters of victims. “I just couldn’t be home anymore.”

His family has been asked to provide DNA to authorities. He worried what his brother’s death could do to his parents. But he also was ready to start mourning. Holding out hope might only hurt more.

soumya.karlamangla@latimes.com | @skarlamangla

hailey.branson@latimes.com | @haileybranson

sarah.parvini@latimes.com | @sarahparvini

corina.knoll@latimes.com | @corinaknoll

Times staff writer Soumya Karlamangla reported from Oakland and Hailey Branson-Potts, Sarah Parvini and Corina Knoll from Los Angeles. Times staff writers Brittny Mejia and Sonali Kohli contributed to this report.

UPDATES:

9:25 p.m.: This article was updated with a quote from Jennifer Tanouye’s aunt.

This article was originally published at 8:55 p.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.