Bay Area falling behind on quake safety despite booming tech economy

- Share via

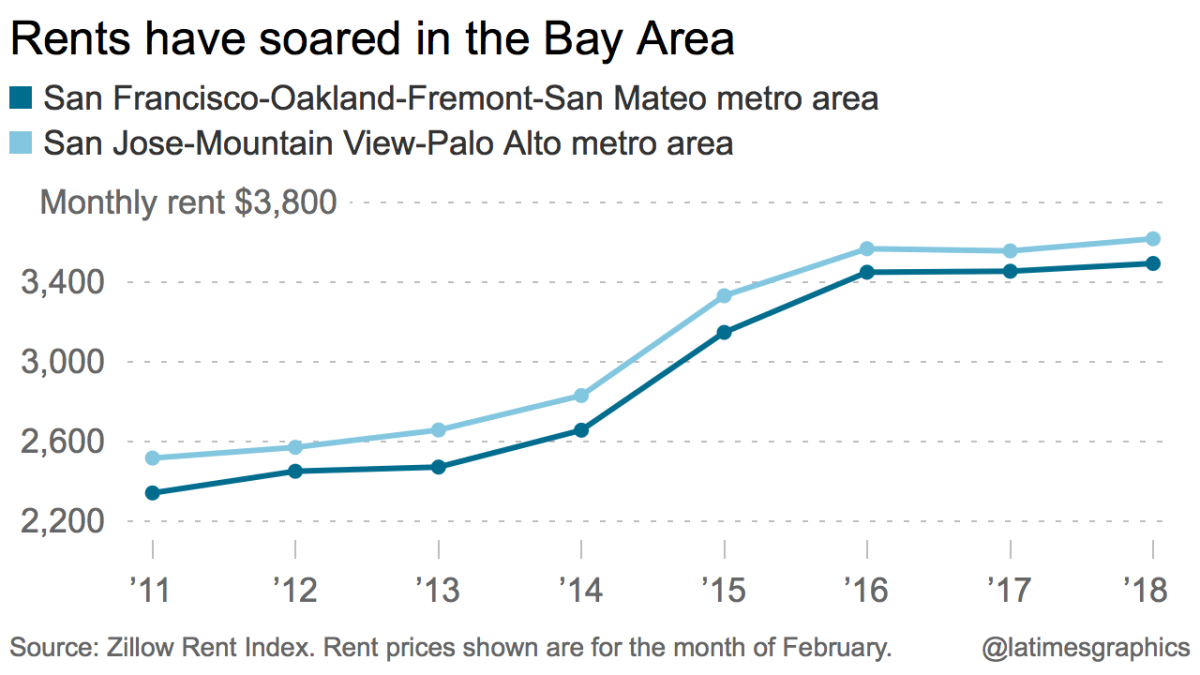

Property values are soaring to stratospheric levels. The tech economy is booming, fueling fast-paced development and spending on home renovations that ranks among the nation’s highest.

But at a time of unparalleled prosperity in the Bay Area, there is growing concern that the region is not using more of its largesse to prepare for its greatest natural threat: a major earthquake.

The Bay Area was once the national leader in seismic safety. Just five years ago, San Francisco made history by becoming the first of California’s largest cities to require property owners to retrofit wood-frame apartments at serious risk of collapse in a major quake, like the one that destroyed much of the city in 1906.

Since then, however, new efforts have stalled in San Francisco and other surrounding cities, while communities in Southern California have expanded mandatory seismic retrofitting efforts. Some quake safety experts worry the Bay Area is missing a key opportunity to take advantage of the booming economy to make more fixes.

There are an estimated 2,000 to 3,000 brittle concrete buildings in San Francisco — a building type that is one of the deadliest in earthquakes — yet the city does not have a list of where they are located.

In Oakland, there are nearly 2,000 possibly vulnerable wood-frame apartment buildings at risk of collapse in a seismic event — and there is no law to require them to be fixed. San Jose doesn’t even have a list of its more than 1,000 apartment buildings thought to be at risk.

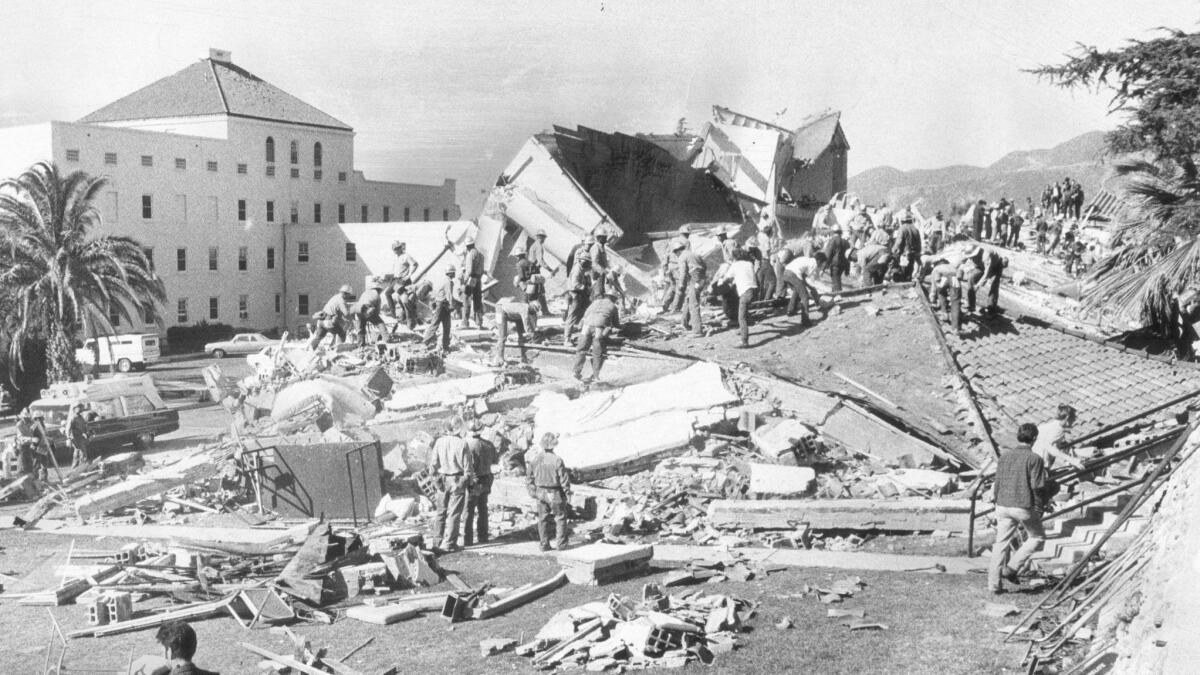

Across the Bay Area, there are an estimated 18,000 vulnerable wood-frame “soft-story” buildings — with about 140,000 residential units — which can collapse when upper stories fall on the flimsy ground story holding parking or stores. Sixteen people died when such an apartment complex collapsed on the ground story in the 1994 Northridge earthquake; about 200 other soft-story buildings were damaged or destroyed.

The Bay Area has become “rather complacent about how we stand as far as the risk…. People are very — I don’t know — afraid of jumping into this retrofit issue,” said Arrietta Chakos, policy advisor to the resilience program at the Assn. of Bay Area Governments. “It’s a deep concern for me that people aren’t saying, ‘We just have to do this.’ ”

Some Bay Area cities acknowledge they’re behind and are hoping to catch up. Others defend their approach, saying they’re moving in a thoughtful, methodical manner needed to painstakingly gather political consensus.

“Don’t be too impressed by starting quickly. The question is when you finish,” said David Bonowitz, a structural engineer consulting with the Applied Technology Council, which is assisting San Francisco on seismic safety issues.

Cities across California have struggled to protect buildings against the threat of big quakes — in part because there has not been a catastrophic temblor in the state’s most populated areas in more than 20 years, since the 1994 Northridge quake. This lull has reduced the urgency for improvements. A series of big quakes between 1971 and 1994 prompted huge spending on quake retrofits, including fixes to old brick buildings in some big cities, requirements for better-built hospitals and billions of dollars to strengthen or replace state-owned freeways and bridges.

In recent years, however, Los Angeles and a few Southern California cities have taken the lead in seismic safety requirements, with L.A. as well as Santa Monica and West Hollywood requiring fixes to wood-frame apartments and concrete buildings. Vulnerable steel-frame buildings in West Hollywood and Santa Monica are also now required to be retrofitted.

Other Southern California cities are poised to act. Long Beach is weighing the creation of its own inventory of earthquake-vulnerable buildings. Moorpark has already ordered its own list, and Malibu, Ventura and Hermosa Beach are talking about doing the same. The Southern California Assn. of Governments is assisting cities interested in following L.A.’s lead.

Both the L.A. region and the Bay Area face a major threat of big quakes. A landmark study by the U.S. Geological Survey unveiled last week showed how the Hayward fault in the East Bay is potentially more dangerous than the San Andreas fault in the Bay Area.

There have been a number of seismic safety accomplishments in the Bay Area since the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake.

Besides San Francisco, Berkeley in 2014 and Fremont in 2007 mandated retrofits of soft-story buildings.

In Berkeley, about 70% of the city’s 272 soft-story buildings with five or more units have been retrofitted, said city spokesman Matthai Chakko. Officials are now looking at other problem buildings, and they recently found 111 brittle concrete buildings and 510 “rigid wall-flexible diaphragm” buildings, such as concrete tilt-ups that are commonly used in big-box store construction. The city is considering a voluntary retrofit program.

All 27 soft-story buildings known to city officials in Fremont have been retrofitted, said building official Gary West.

Alameda in 2009 required soft-story apartment owners to hire an engineer to assess the building’s vulnerability, and that prompted many owners to voluntarily retrofit them. Out of 184 soft-story buildings, about 60% have been retrofitted, building official Gregory McFann said.

But there has been a dearth of new mandatory earthquake safety policies in the Bay Area in recent years.

Some suggest the booming economy is a good time to get owners to retrofit. The average market price per unit for apartment buildings has doubled in the last decade in the Bay Area’s biggest cities, according to CoStar Group. In Oakland, the price per unit has jumped from $176,500 to $356,100; in San Jose, from $197,400 to $393,500; and in San Francisco, from $274,500 to $565,400.

“Current owners, if they purchased in the past, should be able to refinance at lower interest rates … and put some of that equity toward retrofitting,” said Jesse Gundersheim, market economist for CoStar Group in San Francisco. Interest rates, while they have risen since 2016, “are still low by historical standards.”

If the Bay Area is looking at what will protect the economy after an earthquake strikes, said Grace Kang, a past president of the Structural Engineers Assn. of Northern California, “perhaps part of the investment of the boom time could be into bolstering the community infrastructure — where we live, so we can go back into our homes.”

Structural engineer Janiele Maffei, former board member of the Oakland-based Earthquake Engineering Research Institute, said she likes the idea of jumping into programs: “The minute you start that clock, you’re ahead. The minute you say you’re not going to start that clock for 10 years, you’re behind.”

For Dave Guarino, a 32-year-old Oakland resident, the issue is personal.

Four years ago, Guarino stumbled upon an Assn. of Bay Area Governments report on the seismic threat to Oakland’s housing supply. The report said 17,000 units in Oakland’s soft-story apartments or condominiums could be declared uninhabitable after a major earthquake — 10% of the city’s housing supply.

Worried about his own safety and his neighbors, Guarino got the city’s list of possibly vulnerable apartment buildings. His building was on it. He and others mapped out the city’s entire list on a website. He’s asked City Hall for help. Yet four years later, no proposal for a mandatory retrofit law has been introduced by the City Council.

“I love my neighborhood. That’s why I don’t want everyone to have to move out because everything falls apart,” Guarino said on a recent sunny weekday morning. “Every day that we don’t do it is a day that we risk more people dying. More people getting hurt. More people getting displaced.”

City officials said they are trying.

Oakland Councilman Dan Kalb said he has been working on and off in recent years to pass a mandatory soft-story retrofit law. But in 2016, he said, his council colleagues asked him to put the issue on the back burner.

After he began working on the issue again last year, he was told the issue needed to be heard by the Planning Commission — and that panel still hasn’t put the topic on its agenda.

“I’ve been frustrated by the delays as well,” Kalb said.

GRAPHIC: How an earthquake can bring down an apartment »

The housing security policy director for Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf, Darin Ranelletti, said the mayor recognizes the need for a mandatory soft-story retrofit law and hoped that the issue would be taken up this year.

In San Jose, officials acknowledge being late to the seismic safety problem. But that began to change after City Hall was left red-faced when floodwaters from Coyote Creek poured into homes last year with little to no official warning. City officials said they thought they handled the recovery effort well but realized how overwhelmed they might be in a major earthquake.

“That served as a real wake-up call,” said Kip Harkness, deputy city manager for San Jose. The city is now working to create a list of soft-story buildings and applying for a Federal Emergency Management Agency grant this summer that could help start funding the creation of the inventory by fall.

San Francisco has been dealing with a number of seismic issues, such as requiring seismic evaluations of private schools and asking voters for a $425-million bond to begin fixing the vulnerable seawall that supports the Embarcadero.

But mandating the retrofit of brittle concrete or steel-frame buildings has not been on the immediate agenda in San Francisco.

The collapse of brittle concrete or steel-frame buildings can be extremely deadly, given their vast size. Brittle concrete buildings pose one of the greatest risks to life in an earthquake; 52 people died from such collapsed buildings in the 1971 Sylmar earthquake. A steel-frame building housing the Automobile Club of Southern California in Santa Clarita came very close to collapse in the 1994 Northridge earthquake.

GRAPHIC: How concrete buildings fail in earthquakes »

Though Los Angeles, Santa Monica and West Hollywood have managed to create lists of suspected brittle concrete buildings, San Francisco’s new chief resilience officer, Brian Strong, contended it would be difficult to do so in his city.

“It’s not a particularly easy thing to identify,” Strong said. Finding the buildings will be the city’s next step, he said. “That’s probably an expensive undertaking. And then understanding what do people do with these buildings is another challenge.”

Bonowitz, the structural engineer consulting with Strong, said San Francisco has an older, larger and more complicated stock of brittle concrete buildings than Los Angeles, and may want a different approach, like prioritizing retrofits of certain concrete buildings first.

“We want to be able to make the case that whatever buildings that are on the list are known legitimate risks. And that because of their uses, they represent something that can really cripple the city,” Bonowitz said. “It’s just going to start slower because of the more cautious, consensus approach up here. We’re big on meetings and community buy-in, and that takes time. But when we get it, we go.”

Last year, Palo Alto received an exhaustive study of its own inventory of vulnerable buildings, which was then referred to a City Council committee to discuss it further sometime this year. A meeting to discuss the issue has yet to be scheduled.

Back in Oakland, Guarino said he fears that renters whose homes are destroyed in an earthquake will be priced out of the city when their older affordable housing units are gone.

“The scale of the problem is such that you need the scale of government to fix it,” he said.

Twitter: @ronlin

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.