After 15 hepatitis deaths, San Diego County declares local health emergency

San Diego County declared a local health emergency Friday night, adding a new level of urgency to a hepatitis A outbreak that has hit hardest among tthe homeless population, killing 15 people and hospitalizing hundreds.

The declaration by Dr. Wilma Wooten, the region’s public health officer, bolsters the county Health and Human Services Agency’s ability to request assistance from the state and provides legal protections for a slate of actions that began unfolding across the city earlier in the day.

Working on a county contract, a private company began delivering portable hand-washing stations Friday morning in locations where homeless residents tend to congregate. Twenty stations were in place by the end of the day and 20 more were scheduled for installation Saturday, a county spokesman said.

That effort is to be followed by street-cleaning crews shooting high-pressure water spiked with bleach to remove “all feces, blood, bodily fluids or contaminated surfaces,” according to a sanitation plan included in a letter delivered to city government Thursday.

The cleaning plans, Wooten said, are modeled on similar efforts used to control hepatitis A infections in Los Angeles.

“We know that L.A. has had no local cases of hepatitis A related to the strain that we’re seeing here in San Diego,” she said. “It makes sense that, if they’re doing it there and they haven’t had any cases, it could be beneficial here as well.”

It has been clear for some time that the local outbreak is far beyond ordinary. With 379 cases confirmed to date, it’s the largest surge seen in at least 20 years.

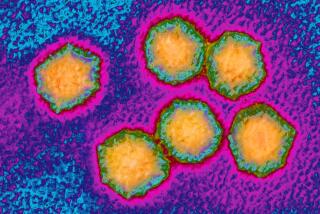

The first cases linked to the outbreak occurred in November 2016, but there weren’t enough of them until this past spring for local epidemiologists to know for sure that infections were spreading more quickly than usual. Most hepatitis A outbreaks are associated with specific foods picked or processed under unsanitary conditions. The virus that causes the condition lives in human feces and is spread when people don’t wash their hands thoroughly after using the bathroom.

From the outset, the public health response to the outbreak has been vaccination and education. Though thousands of doses of vaccine have been distributed to date, that effort has not appreciably slowed infection rates, while the number of deaths reported in recent weeks has accelerated.

Because infections are most common among the homeless who often have no access to sanitary facilities, the county’s efforts began to turn toward hand-washing and street cleaning in early summer.

But that transition has been painfully slow.

Sisson writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.