Must Reads: Firefighters’ fateful choices: How the Woolsey fire became an unstoppable monster

It was clear from the beginning that the Woolsey fire had the potential to be a monster.

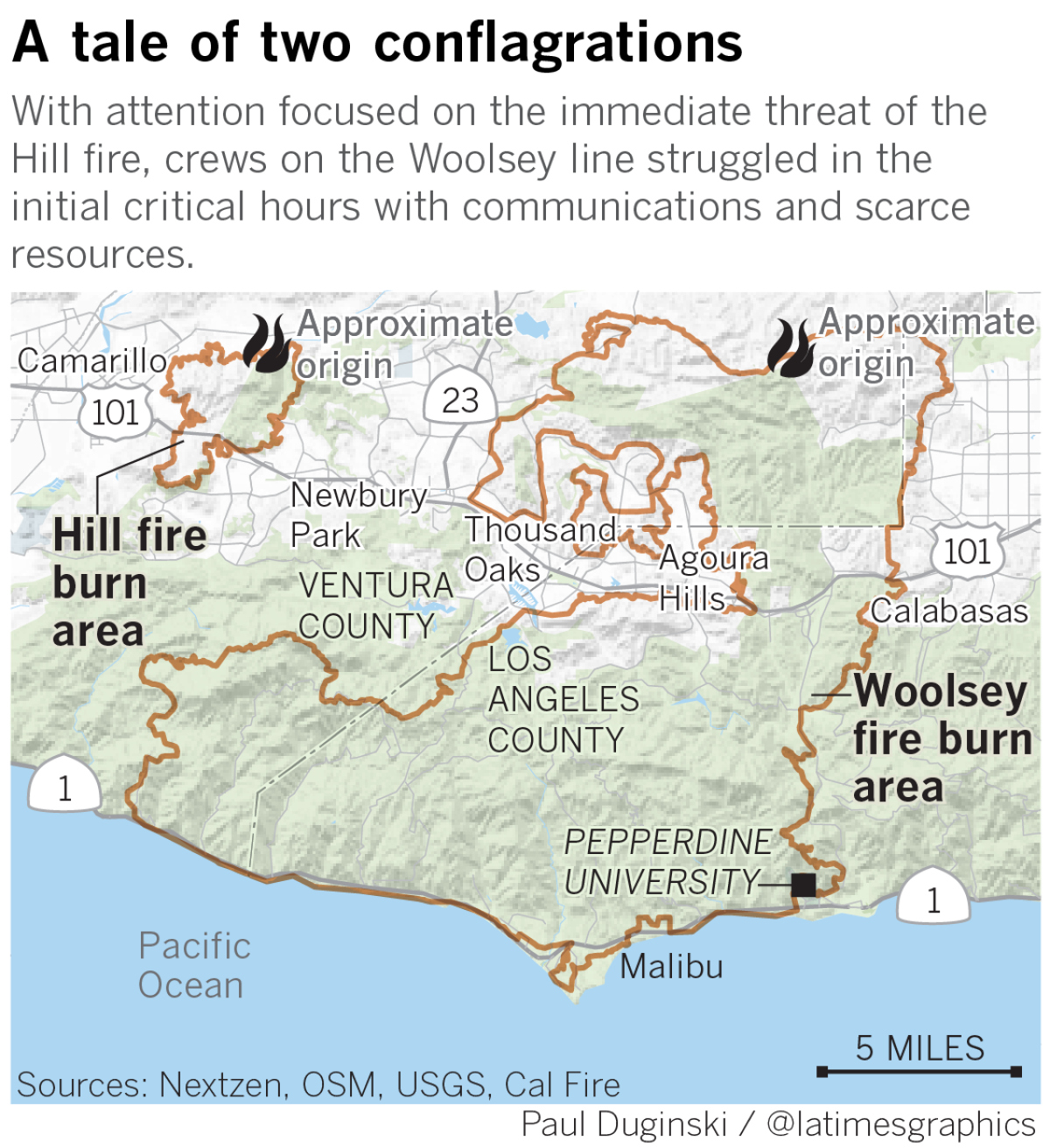

It broke out mid-afternoon Nov. 8 on Boeing property near the Santa Susana Pass, fueled by strengthening winds and burning toward populated areas.

But during the critical first hours, the Woolsey fire took second priority.

Ventura County firefighters were already engaged in a pitched battle with another blaze, called the Hill fire, about 15 miles to the west that had jumped the 101 Freeway and was threatening hundreds of homes and businesses.

The Woolsey fire was growing but still far enough from subdivisions that it got fewer resources from Ventura County. Neighboring fire agencies sent some help, but it would take hours before they launched an all-out attack at the fire lines.

These turned out to be fateful choices in what would become the most destructive fire in Los Angeles and Ventura county history.

A Times review of hundreds of pages of public records and several hours of radio transmissions shows that first responders on the front lines of the Woolsey fire struggled during those first critical hours, stymied by communication breakdowns and a scarcity of air tanker support, equipment and firefighters.

Los Angeles County Fire Department sent some firefighters to the front lines but decided early on to deploy dozens more several miles away in the Agoura Hills area, according to interviews, incident logs and planning reports obtained under the California Public Records Act.

L.A. County Fire Capt. Tony Imbrenda said the department knew the fire was headed toward L.A. County and staged four strike teams — 20 engines and 88 firefighters total — in Agoura Hills to assess how the fire would affect homes and businesses once it reached the area.

Imbrenda said the department didn’t send the strike teams, each comprising five engines and 22 firefighters, directly to the Woolsey fire line “because the fire hadn’t crossed into L.A. County yet. These resources were all set up to protect L.A. County.”

Imbrenda said sending the strike teams to the fire line earlier would not have made a difference. “There was no way, no engine, no apparatus, no aircraft in this world that could have possibly stopped that fire from making it to L.A. County,” he said.

The Los Angeles Fire Department, the city’s fire agency, also sent engines toward the Woolsey fire, but its firefighters seemed to grow frustrated with the lack of a plan and resources on the scene, according to radio transmissions. Some firefighters said in radio transmissions they were hampered by a lack of water at the Boeing facility and by poor cellphone service, which forced them to move the command center to a Ventura County fire station.

By 5 p.m., the L.A. city fire department had completed a map modeling how the Woolsey fire would burn, showing with a high degree of accuracy its ultimate path through Bell Canyon, the Santa Monica Mountains and Oak Park.

Even as the Woolsey fire worsened through that first afternoon and evening, firefighters struggled to get more boots on the ground. By 7:30 p.m., the Hill fire was being battled by 400 personnel while only 150 firefighters from three agencies were on the Woolsey fire, according to incident updates released by fire officials.

Over the next three days, the Woolsey fire made a devastating march to the Pacific Ocean, destroying more than 1,500 structures from Oak Park to Malibu, burning almost 97,000 acres and killing three people.

The Hill fire, by contrast, destroyed just four structures and burned 4,500 acres.

A tale of two fires

The Woolsey fire started at 2:24 p.m. on the site of the old Santa Susana test lab near Simi Valley, with a column of smoke visible on what was a clear day across eastern Ventura County.

“Do you have eyes on where that smoke’s coming from?” a Ventura County firefighter asked another firefighter on his way.

It would take almost 20 minutes for the first unit to arrive, a Ventura County engine carrying three firefighters, driving from their Simi Valley station about eight miles away, according to incident logs and interviews.

When a helicopter from the Los Angeles County Fire Department arrived about 2:50 p.m., a crew member estimated the Woolsey fire to be about five acres with a rapid rate of spread and structures threatened. Over the dispatch, the crew member reported a southeast wind of about 25 to 30 miles per hour.

Do you have eyes on where that smoke’s coming from?

The area where the fire started, at the Santa Susana Field Laboratory, is located near the Los Angeles and Ventura County line in a “mutual threat zone,” an area that the Los Angeles County Fire Department, Ventura County Fire Department and Los Angeles Fire Department have agreed, through a memorandum of understanding, to defend together because of the threat a fire there poses to each agency’s communities. Each year, firefighters from the three departments train together in the Santa Susana area to prepare for a fire. Their most recent training was in June.

The operating plan created and signed by the three agencies outlines the number of firefighters and amount of equipment they’ll each send as part of their initial attack.

On Nov. 8, as the fire started burning, the plan called for Ventura County Fire to send a full brush response, a team of firefighters that includes five to six fire engines, a bulldozer and a helicopter. Instead, within the first hour of the fire, Ventura County sent only two engines and about 12 firefighters.

That’s because at 2:03 p.m., 21 minutes before the Woolsey fire started burning, a Ventura County helicopter spotted a fire burning in Santa Rosa Valley, north of the 101 between Camarillo and Newbury Park. This would become the Hill fire.

Soon, there would be two fires in a county that had already experienced incredible tragedy just 15 hours earlier — the shooting at the Borderline Bar and Grill in Thousand Oaks, where 12 people were shot and killed.

Ventura County officials say the Hill fire took priority over the Woolsey fire because it was an immediate threat to lives and homes.

The Hill fire grew to 100 acres in the first 15 minutes. It jumped the 101 even sooner, in 12 minutes, and when the California Highway Patrol shut down the freeway, several drivers were trapped when they tried to go around the roadblock and drove directly into the blaze.

Cal State Channel Islands was evacuated. Calls poured into the Ventura County dispatch center from residents who were older or with disabilities asking for help in evacuating. Sheriff’s deputies got boxed in while trying to evacuate people and, at least once, needed helicopters to make water drops near them so they could escape.

Ventura County Fire Assistant Chief Dustin Gardner, who oversaw resources for the Hill and Woolsey fires, said it was clear from the beginning that the Hill fire was initially more dangerous.

By 4:10 p.m., the Hill fire hit open space that had burned in 2013 during an earlier fire. It began to burn more slowly east of Camarillo and largely stopped sending embers downwind. For the next several hours, firefighters worked to curtail other sections of the blaze. About midnight, as the Woolsey fire began burning into Oak Park, the Hill fire danger had subsided enough that officials started diverting an army of resources from the blaze to the Woolsey, Gardner said.

Gardner remembered the Hill fire commanders’ concern when he told them to pull every resource they could and send it to the Woolsey fire.

“We still have a 5,000-acre fire here,” a commander responded.

Gardner said although they knew the Hill fire could keep growing, the Woolsey fire was now threatening human lives.

“From just looking at it, it looks like the response to the Woolsey fire was less than the response to the Hill fire,” Gardner said. “Put it in a perspective of managing the area, of looking at the totality of both fires and doing the best you can with what you have at the time you have it.

“There was never any decision made that one fire was more important, per se, than another. The decisions were based on what was best for the most people with what we had at the time we were presented with it,” he added.

There was never any decision made that one fire was more important, per se, than another.

— Ventura County Fire Assistant Chief Dustin Gardner

Both fires were driven by the same powerful Santa Ana winds.

But at least at the beginning, the two fires behaved differently. Gardner said the origin of the Woolsey fire was in an area with topography that shielded it from some of the most powerful wind gusts, which were blowing at 37 mph when the blaze first began.

This made it spread slower than the Hill fire — at least at first, Gardner said. The Woolsey fire grew to 750 acres within its first two hours, compared to the Hill fire, which officials initially said scorched 8,000 to 10,000 acres in its first 30 minutes.

Certain details of the first hour or so of the Woolsey fire remain a mystery. The fire began near a Southern California Edison substation that experienced issues shortly before the Woolsey fire started, and the utility has said it’s investigating whether its equipment sparked the blaze.

It remains unclear what role, if any, Boeing’s firefighting and security staff had in dealing with the fire. Boeing has a private fire department on site at Santa Susana Field Laboratory, according to the California Department of Toxic Substances Control.

Boeing has repeatedly declined to answer questions from The Times about its firefighters’ efforts.

The company did not provide answers when asked how many firefighters work on the grounds, how many engines they have and what type of equipment they used to try to stop the fire.

Instead, the company said in a statement that its fire and security personnel “responded to the fire that began on November 8 and provided assistance to local municipal and county fire crews as they responded to the scene.”

Officials with Ventura County Fire Department said they didn’t remember seeing or communicating with any Boeing firefighters.

Los Angeles County Fire Department said in a statement that they had “little to no interactions” with any Boeing firefighters, as was the case for LAFD.

“I was at the incident command post,” said LAFD Deputy Chief Trevor Richmond. “I was there with Ventura County and L.A. County Fire, and I do not recall seeing anyone from Boeing, and I did not interact with anyone from Boeing.”

Because of the rocky, hilly terrain where the blaze started, aircraft had the potential to play an important role in fighting the Woolsey fire, making water and retardant drops on ridges which ground troops cannot reach.

Ventura County had two helicopters that flew through the night on both fires. LAFD sent three of its helicopters capable of flying at night, but they had all returned from the Woolsey fire by 6:30 p.m. (An agency spokeswoman said the decision to send the helicopters home would have come from the team managing the fire, not LAFD.)

L.A. County Fire initially sent three helicopters; a pair of Bombardier CL-415 air tankers that can each hold 1,620 gallons of water at one time — commonly referred to as Super Scoopers; and an Erickson Helitanker, which has a 2,650-gallon water tank.

However, once nightfall hit, their aircraft had limited effectiveness because of the high winds gusting over the region.

“Air attack resources were severely hampered by wind on the Woolsey fire,” Imbrenda, a public information officer with L.A. County Fire, said in an email. “Once we have sustained winds of 40 mph, air drops become ineffective. Firehawk helicopters flew in support of ground operations throughout the night on Nov. 8. All other air resources were grounded due to high winds.”

One of the additional challenges that the Woolsey incident commander faced was getting air tankers.

Whereas helicopters are primarily used for direct attack, dropping water on active fire, air tankers are often used to drop pink retardant along ridges and mountainsides to create or improve control lines around the fire.

On Nov. 8, air tankers — which don’t fly at night — were in high demand, Gardner said. The deadly Camp fire had started in Northern California the same day at 6:33 a.m., and officials from all three fires were calling state emergency leaders asking them to send help.

Gardner said he was repeatedly on the phone begging the state to send more tankers to Ventura County, arguing the Woolsey fire had the potential to hit Malibu, not realizing how bad the Camp fire had become.

Within the first hour of the Hill fire, the incident commander doubled his order from four to eight air tankers.

Soon after, a dispatcher asked him if they could divert one of his fire’s tankers to the Woolsey fire, which was potentially going to threaten homes and businesses in Simi Valley.

“You can divert one of the air tankers,” Ventura County Fire Assistant Chief Chad Cook, the Hill fire incident commander, said. “We’ll keep the rest of them here.”

About 40 minutes later, at 3:37 p.m., a dispatcher told the Hill fire incident commander two air tankers and two helitankers would soon arrive to fight the blaze. Only a few minutes later, the Woolsey incident commander was told by a dispatcher that the region had no more air tankers it could send, but that there were multiple helicopters available.

About an hour later, the Woolsey incident commander seemed to be frustrated by his tanker requests going unfilled.

“I'd like to talk to my neighboring fire (commander) and see if I can get some from him,” the Woolsey incident commander told his aerial coordinator over the radio at 4:26 p.m.

“Correct, sir,” the aerial coordinator said. “We’ve been trying to negotiate resource sharing. We’ll see how that goes.”

But the Woolsey fire began spreading at a much faster pace — with far fewer firefighters on the ground than were battling the Hill fire.

A question of resources

With the Ventura County Fire Department consumed by the Hill fire, it was going to be up to neighboring agencies to help battle the Woolsey fire.

And the location of the Woolsey fire seemed to make mutual aid achievable, with it burning along the Los Angeles County line not far from both L.A. city and county fire stations.

The agency to send the most fire engines in the first hours of the Woolsey fire was LAFD.

Richmond, the LAFD’s Valley bureau commander, said in an interview that he, along with other fire leaders working the Woolsey fire, discussed early on that they knew this fire would get serious quickly.

“At the end of the day, the concern, from my perspective on this incident, is obviously (we’re) looking out for L.A. city and making sure that our assets and risks are protected, and if that means dropping water on a Ventura County fire, and it will help us down the road, that’s what we’re going to do,” Richmond said.

Firefighters from LAFD started streaming in less than a half-hour after the fire began.

Radio transmissions show, soon after they arrived, the firefighters started placing hoses around the fire, giving them quick access to water, and assessing the size and direction of the fire. Within an hour, 11 fire engines and two fire trucks had arrived.

We’re still coming up with a game plan.

Shortly after they arrived, an LAFD firefighter with Engine 481 asked Engine 28 to drive over and help them establish a fire line. But Engine 28 responded that the winds were shifting and they needed to stay put.

“There’s no more resources where we’re at,” an Engine 28 firefighter said.

“Roger that,” the firefighter on Engine 481 responded. “We’ll figure something else out.”

Repeatedly over the next hour, the crew’s battalion chief remarked that the fire’s leaders were still establishing a plan and noted, “We’re having issues with communications right now.” The firefighters discussed how, because of a limited number of hydrants at the Boeing facility, they had to use trucks to keep shuttling water to each other to continue battling the blaze.

L.A. County had about seven engines staging near the Boeing gate when the county’s first strike team arrived about 3:30 p.m. and radioed in seeking orders.

“We’re still coming up with a game plan,” a fire leader responded.

Gardner, the Ventura County assistant chief, said the plan referenced was fire leaders developing their control objectives and other advanced strategic decisions, but that this wouldn’t have kept firefighters on the ground from actively fighting the fire.

The LAFD continued to send more ground troops than L.A. County into the zone over the next few hours, according to state mutual aid data and incident logs.

Meanwhile, the county fire department was amassing an army of engines at Fire Station 89 in Agoura Hills. By 4:33 p.m., four strike teams were in place there.

Imbrenda said the strike teams were used to assess neighborhoods in L.A. County that county fire leaders believed would eventually be in the path of the Woolsey fire. Those assessments were used to create a firefighting strategy for the area, he said.

L.A. County’s incident log, dispatch recordings and the state mutual aid data reviewed by The Times show those four strike teams did not arrive at the Woolsey fire line until just after 9 p.m. By then, the fire was approaching Oak Park, which is about three miles north of Fire Station 89.

At 8:54 p.m., Ventura County Fire Capt. Jeff Pike, the Woolsey incident commander, told Ventura County Division Chief John McNeil over the radio that fire activity was picking up, and that he expected the blaze to reach Oak Park in about an hour. He said he wanted five strike teams to defend Oak Park, according to radio transmissions.

“It’s my understanding we might have some L.A. County resources, staged at (Fire Station) 89,” Pike said. “If we could use those resources with the understanding that if L.A. County gets impacted, we can bump those resources back into the L.A. County area.”

About eight minutes later, at about 9:02 p.m., an L.A. County firefighter radioed to dispatchers that the four strike teams from Station 89 were responding to the blaze.

The county fire department disputes this chronology, insisting the strike teams arrived hours earlier than the records indicate, and that the arrival time that’s reflected in the records was a data entry error.

But officials would not provide any further documentation of the teams’ exact arrival times.

Imbrenda cautioned The Times that the radio transmissions it reviewed might not include all tactical communications and that the broadcast could include erroneous reports from civilians.

Station 89 sits along the 101 Freeway. Radio transmissions indicate that just an hour after the Woolsey fire started, one of the L.A. County battalion chiefs overseeing the agency’s Woolsey response wanted to place firefighters on the 101 to prevent the fire from jumping the freeway.

His concern was understandable — history has shown that, once a fire crosses the freeway, it can easily make a run for the beach communities.

Los Angeles County Fire Chief Daryl L. Osby defended his department’s tactics, though he stressed he could not speak to specific actions, including when the strike teams arrived and how they were used.

He said it made sense for firefighters to make a stand at the 101.

Osby said the decision-making focused on protecting lives and property across the entire region and that there was no special focus on areas served by the L.A. County Fire Department.

“When we have fires in that area, we’re aware of the potential of it burning to the 101 Freeway and then the potential of it jumping the 101 Freeway,” he said. “We were aware of the possibility that it could get to the 101 Freeway, so we did all that we could to prevent that.”

We were aware of the possibility that it could get to the 101 Freeway, so we did all that we could to prevent that.

— Los Angeles County Fire Chief Daryl L. Osby

Around midnight, resources were beginning to flood into the Woolsey zone. Some came from the Hill fire, whose danger had lessened. From around midnight to 3 a.m., L.A. County alone sent about 12 more strike teams along with 10 more engines.

Osby said he felt the strike teams arrived at the appropriate times and that his department had more firefighters assigned to the blaze than he could ever remember.

“Over half our department was allocated to this fire, which was really unprecedented practice in my career, and I’ve been here for 30 years,” he said.

But by midnight, the Woolsey fire had grown more powerful and was almost impossible to control at 4,000 acres. Fueled by gusts topping 70 mph, the fire burned homes in Oak Park and forced thousands to evacuate. By 3 a.m., it was 8,000 acres, and at 5:15 a.m. it jumped the 101 Freeway and began its fateful run toward Malibu.

Gardner, the Ventura County assistant fire chief, said he had no issues with the resources L.A. County and city fire provided, calling both agencies “100 percent” supportive during the Woolsey fire.

Making a monster

As far as the Woolsey fire moved that first night, the following day would be much worse. The fire ate into the Santa Monica Mountains, burning 88% of federal parkland. It became 14 miles wide at one point as it devastated Malibu neighborhoods.

Veteran firefighters say it was a once-in-a-lifetime event.

“In my 30 years of experience, I’ve never seen a fire that explosive,” LAFD’s Richmond said. “Seeing how quickly that fire traveled to Agoura Hills and Oak Park and Thousand Oaks and jumped the freeway the next morning, and in four hours, it’s burning kelp beds in the Pacific Ocean — that’s pretty incredible.

“This one was the big one,” he said.

The question officials are facing now is whether different tactics would have stopped the fire sooner.

It’s clear that those fighting the fire in those first few hours didn’t have the resources they thought they needed, according to radio transmissions. It’s also clear tactics used by fire officials that day limited the number of firefighters on the front lines that afternoon and evening.

At public meetings, some residents have complained about a lack of fire resources and what some claim was a flawed evacuation strategy. Both the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors and the Malibu City Council are creating panels to investigate how the fire was fought.

Malibu Mayor Jefferson Wagner, who was injured in a futile attempt to save his home, put it this way: “Part of the healing process includes understanding what happened and why it happened, and making improvements for the future.”

Times staff writers Paul Pringle, Matt Stiles and Richard Winton contributed to this report.

Produced by Sean Greene. Graphics by Priya Krishnakumar and Paul Duginski.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.