Actor Orson Bean, local theater mainstay who rose to fame as a 1950s TV personality, dies

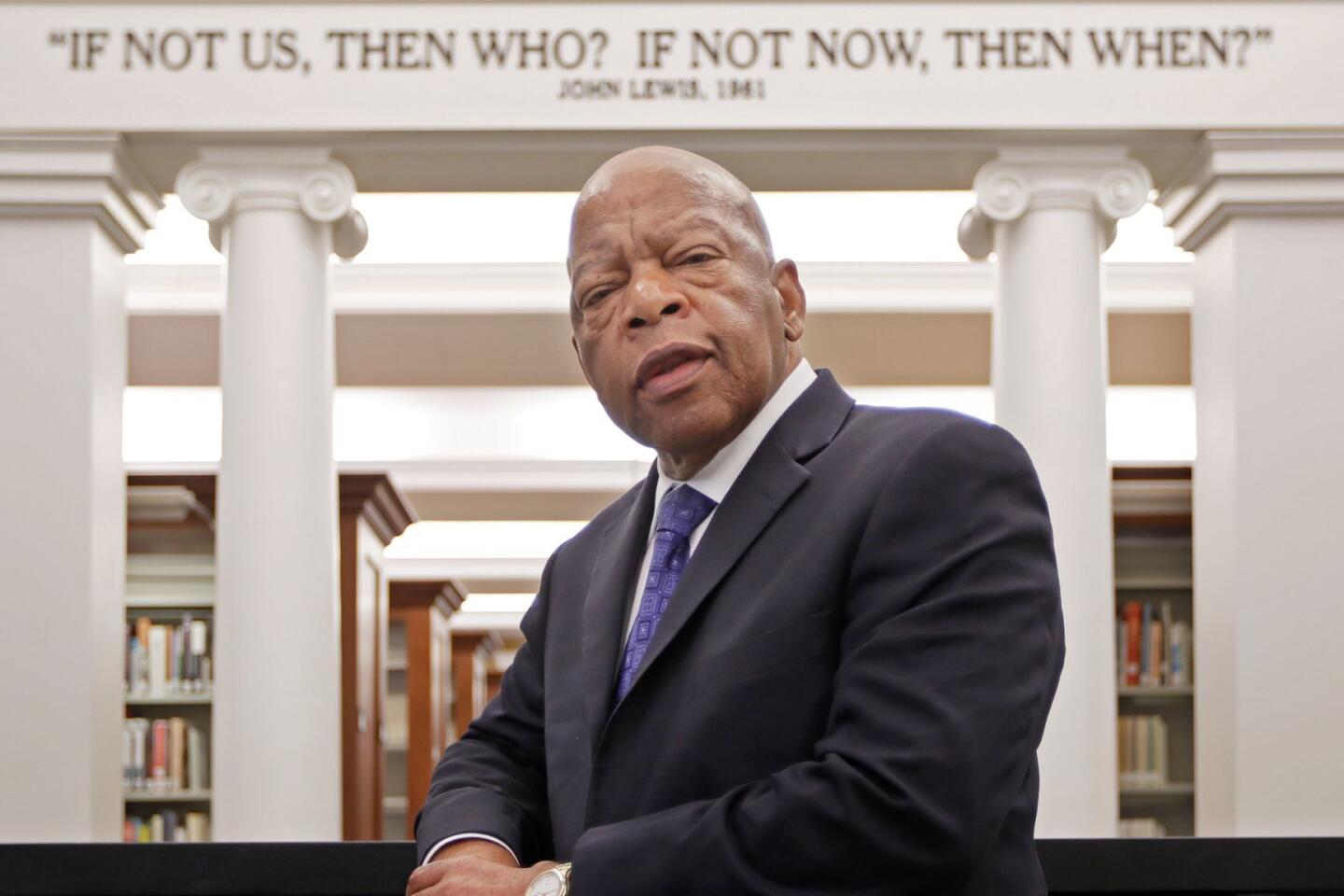

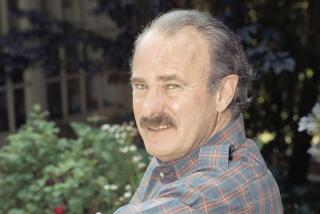

Actor Orson Bean, a veteran television personality, all-around entertainer and master raconteur who worked on the small screen and in film while becoming a mainstay of Los Angeles’ small theater scene, has died.

Bean was hit by two cars and killed Friday night in Los Angeles, authorities said. He was 91.

Orson Bean’s death comes as new figures show that the number of people killed in car crashes in Los Angeles remains stubbornly high.

The showman, a distant cousin of President Coolidge and father-in-law to the late conservative writer Andrew Breitbart, has maintained a steady career since the 1950s and cut his teeth on and off Broadway before becoming a live television staple.

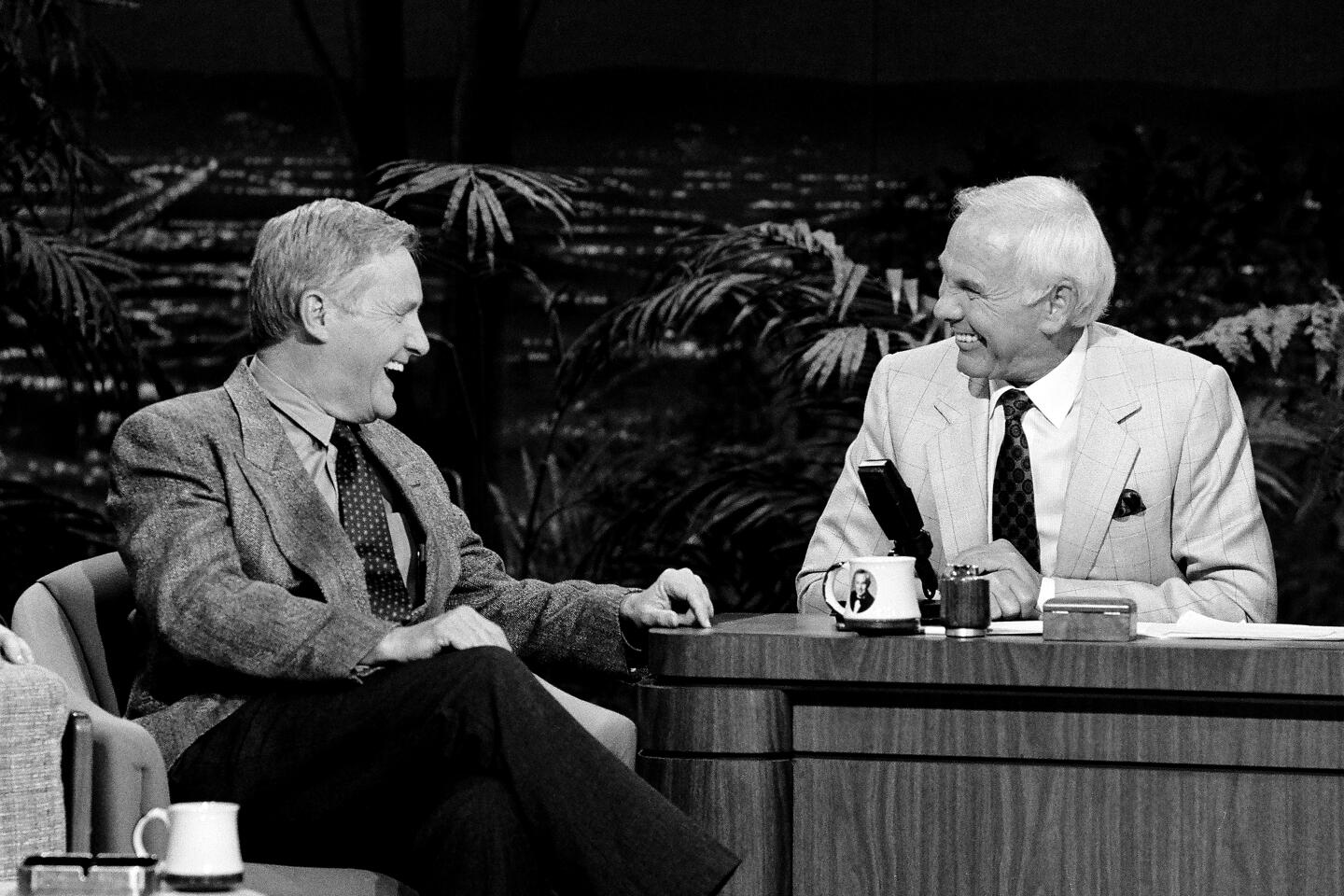

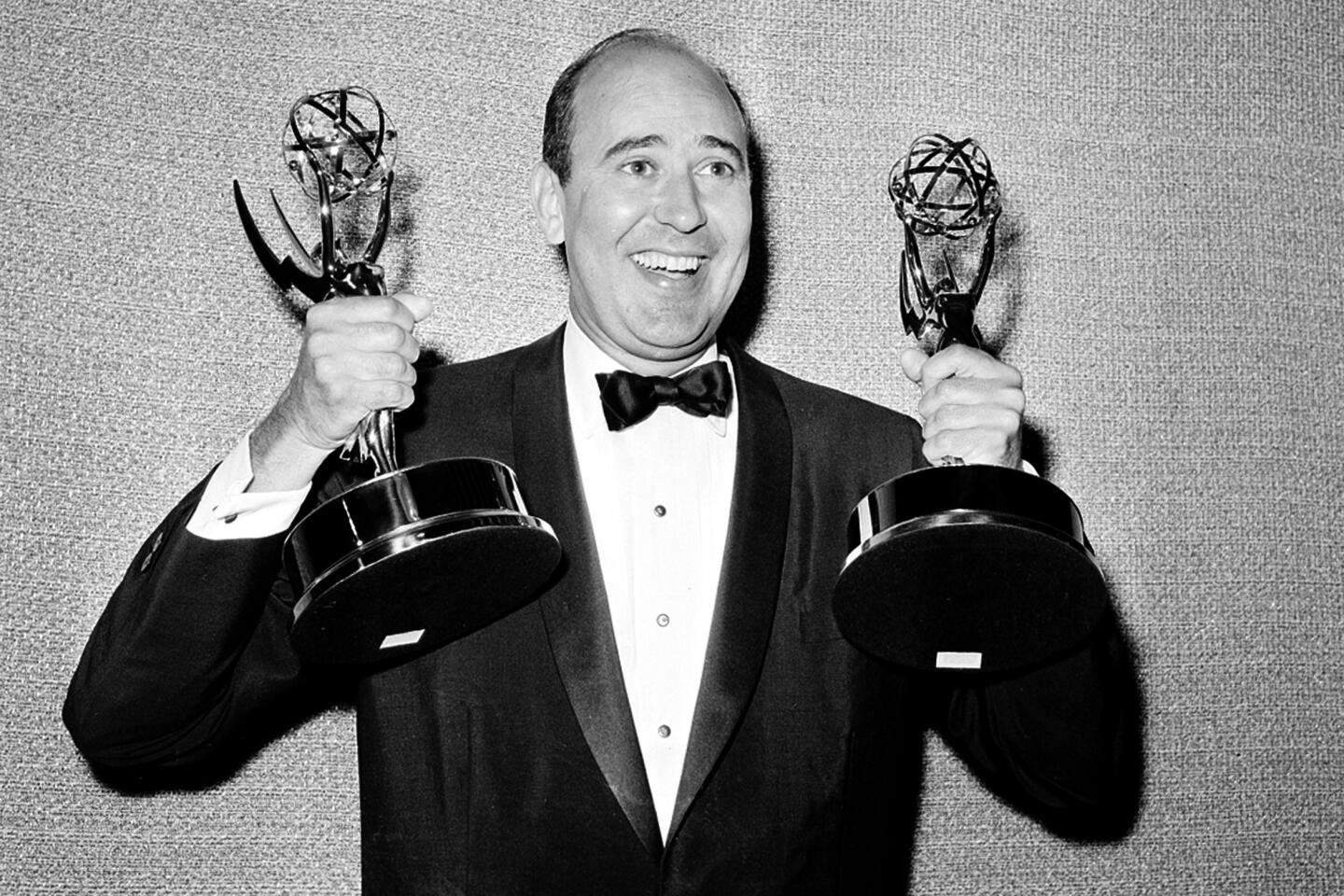

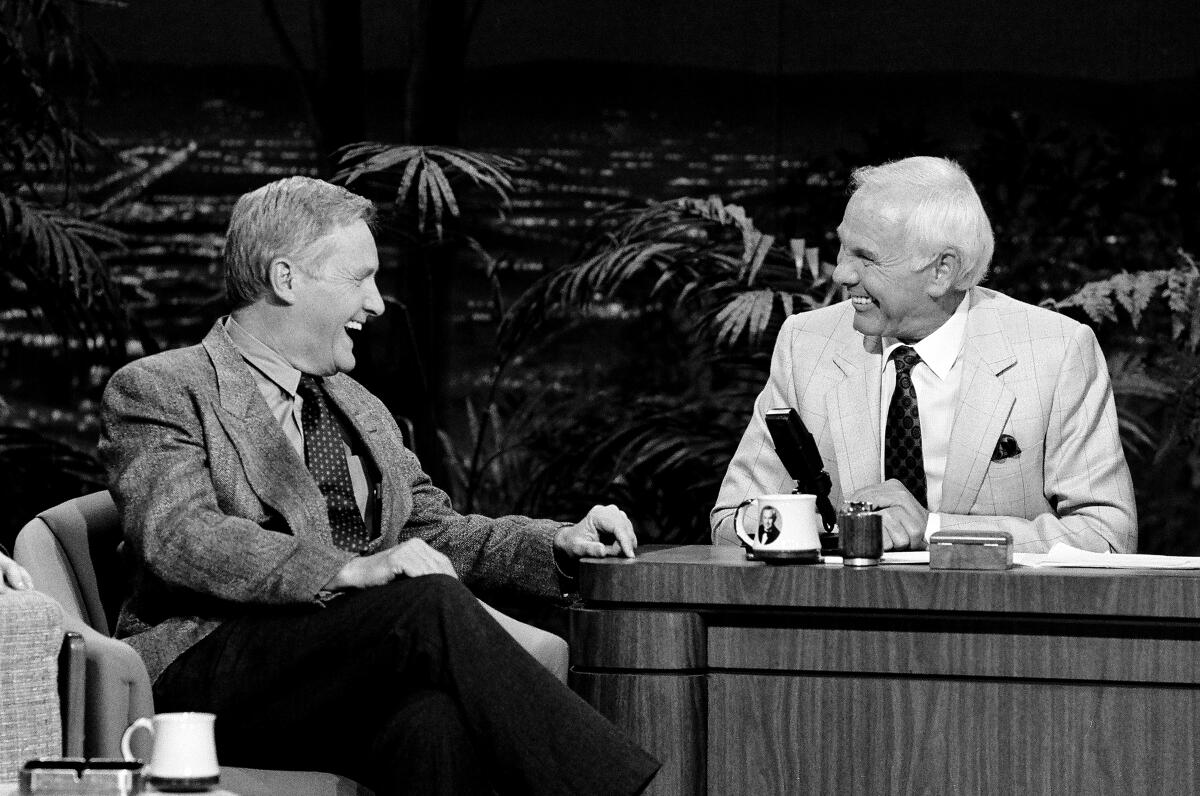

Bean’s onstage antics included stand-up comedy and magic tricks as he made the rounds on game shows and late-night television. He was fondly remembered by baby boomers for bringing his wit and sophistication to “What’s My Line?,” “I’ve Got a Secret” and “To Tell the Truth” and guest-starring in variety series and talk shows, including “The Ed Sullivan Show,” “The Tonight Show starring Johnny Carson” and “The Mike Douglas Show.” Later in his career, he starred in “Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman,” “Being John Malkovich” and “Desperate Housewives” while racking up dozens of guest appearance credits, with “Two and a Half Men,” “The Closer,” “Modern Family” and “How I Met Your Mother” among them.

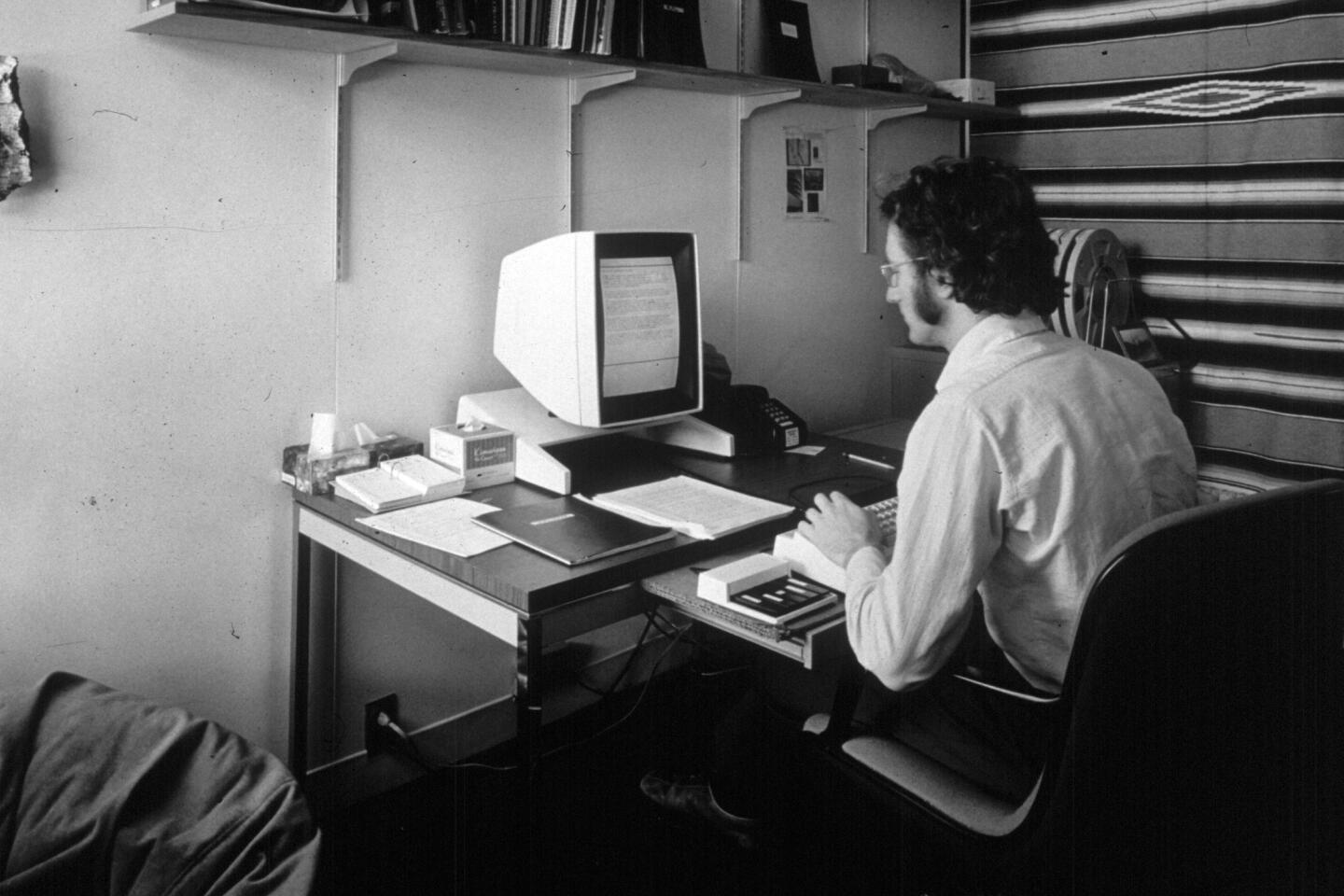

Bean, who wrote several memoirs and a cookbook for cats, was briefly blacklisted, became a hippie, a peddler of a self-help method and a beloved Venice resident as he bolstered the local theater scene with wife Alley Mills. All along, his true passion was the stage, though he acquiesced to television, films and even commercials just to pay his bills.

“Make a living doing commercials or soap operas or tending bar — and then do theater,” he once told The Times. “People shouldn’t get into show business because they want to become stars or become rich; they should get into it because they can’t help but put on a show.”

We knew him as a television personality and master storyteller. Orson Bean’s truest gift may have been his ability to connect with audiences.

Born in Vermont in 1928, Bean, whose real name was Dallas Burrows, grew up during the Great Depression in a cramped Cambridge, Mass., apartment that he shared with his volatile parents. Bean recalled his troublesome childhood in his one-man show “Safe at Home,” which was based on his eponymous memoir. He noted that his parents’ lovemaking was as loud as their screaming fights, and his mother — a jealous type — had a penchant for sherry. She fell apart after his father left home and died by suicide the day after Bean refused her plea to visit her.

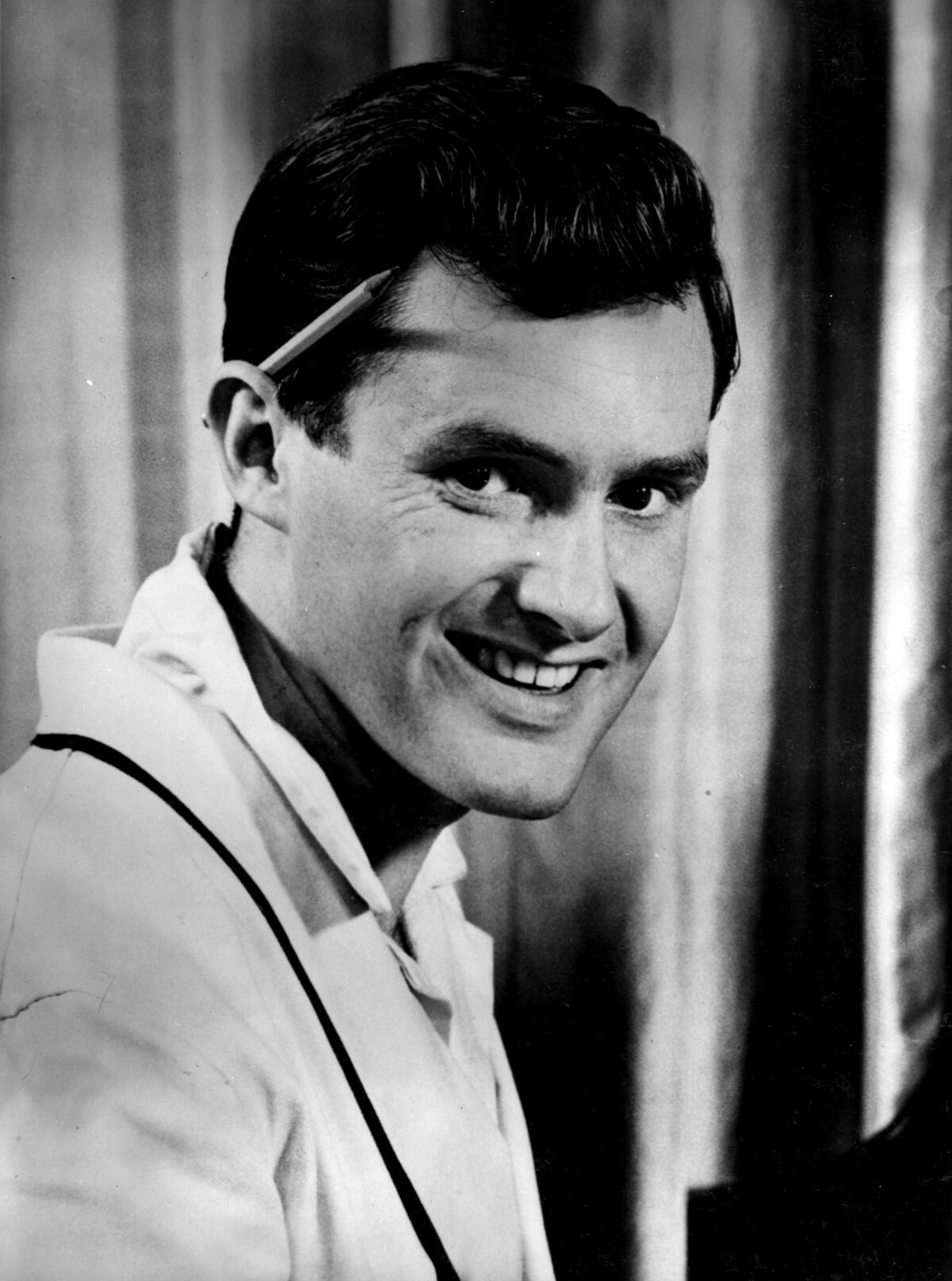

Bean, who said he peed on his cousin — sitting President Coolidge — when he was 6 months old, survived by building a wall around himself and developing a set of entrepreneurial skills that allowed him to make an early break from his mother’s boozy embraces. He began as a magician, mesmerizing the neighborhood kids with his tricks. He tested his sleight of hand on the professional circuit before switching to stand-up comedy when he returned from Japan after World War II. Bean played small clubs near Boston and Philadelphia for a year, honing his acting and writing, before setting out for New York, which opened the doors to “The Ed Sullivan Show” and Broadway.

From 1950 to 1960, he was the house comic at the Blue Angel night club in New York, where he adopted the stage name Orson Bean after workshopping a few other monikers.

“I tried Orson Bean, putting together a pompous first name and a silly second name,” he told the Hollywood Reporter in 2014. “I got laughs, so I decided to keep it. [Filmmaker] Orson Welles himself came into the Blue Angel one night, summoned me to his table. I sat down. He looked at me for a moment and then said, ‘You stole my name!’ And he meant it. Then he dismissed me with a wave of his hand.”

During his two decades in the Big Apple, Bean appeared on and off-Broadway in several starring vehicles such as the comedy “Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?” with Jayne Mansfield and Walter Matthau, and the musicals “John Murray Anderson’s Almanac” and “Subways Are for Sleeping” with Sydney Chaplin. The latter production earned him a 1962 best supporting actor Tony nomination. It was a time “when you could go from one show to another,” he told The Times. In addition to “Sullivan, he acted in TV dramas, including “Philco TV Playhouse” and “The Twilight Zone.”

But the surge in his TV career dried up instantly after he fell for a communist girl — one who “dragged me to a couple of meetings” — and he was blacklisted in the 1950s.

“After I got elected to vice president of the New York local, I got a call from Ed Sullivan. I could feel the blood draining out of my face,” Bean told the Hollywood Reporter. “He said, ‘I have to cancel this Sunday.’ I had been on the show seven times. Overnight, I went from being the hot young comic at CBS to not working. Luckily I got a play that ran for year, ‘Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter.’ ”

Sullivan eventually booked Bean again, he said, noting that “it was Campbell Soup that did the blacklisting, not CBS.” (Later, his son-in-law would write of his “sharp ideological metamorphosis” with Bean telling him it’s “harder now to be an open conservative on a Hollywood set than it was back then to be a Communist.”)

In 1956, he married actress Jacqueline de Sibour, who went by Rain Winslow onstage, and had a daughter named Michele before he and Winslow split in 1962. He got married again in 1965, this time to fashion designer Carolyn Maxwell, and had three children — Max, Susannah (wife of the late Breitbart) and Ezekiel.

During that time, Bean told The Times he became known as a “neo-celebrity who’s famous for being famous” as a panelist on the prime-time game shows “I’ve Got a Secret,” “Password” and “To Tell the Truth.” He was a familiar face on “The Tonight Show” too: Jack Paar and, later, Johnny Carson tapped him to fill in as guest host some 100 times.

After the March 1970 Weather Underground explosion happened around the corner from Bean’s home in Greenwich Village, he tried to relocate with his family to Sydney, Australia: “I turned 40 and ran away from home,” he told The Times in 1989. “I had a lot of money in the bank and I just spent it.”

They returned to the States about a year and a half later.

“I came back, pierced my ear, grew a beard, bought an old van, threw the kids in the back, and we lived like hippies for three years,” he said, noting in his 1988 autobiography that he also experimented with LSD.

After his second wife left him in 1981, he swirled into a life of booze, drugs and loneliness before moving from New York to L.A. to be closer to his kids.

“I did all this stuff, the drugs, getting my kisser on the tube, because I thought it would make me happy. But it didn’t work. I didn’t find happiness until I learned to surrender, to give up the crazy pursuit,” he said. He later wrote “Mail for Mikey” about his addiction and recovery.

He struggled with cash in the 1980s and morosely contemplated his inability to make his house payment.

“Then I rediscovered the one thing I’ve wanted out of life since I was a boy — to be the happiest son of a bitch alive. The next day my agent called with a job to do a commercial voiceover,” he told The Times in 1991, noting that he’d been making a fortune ever since.

Bean also became a spokesman of sorts for psychiatrist Wilhelm Reich’s self-healing theories of the “orgone box” on talk shows. He also wrote a book about the therapy technique, the humorous “Me and the Orgone: One Man’s Sexual Revolution.”

“As far as it goes, it’s wonderful,” Bean told The Times. Reich “was an absolute genius, though absolutely bananas. I still hold him in high regard. I don’t practice, but I do things I learned in therapy, exercises to take anxiety and fear away. I did it for three years, and it’s over with.”

He still kept working, taking on roles in several TV films and series. He voiced Bilbo and Frodo Baggins in the 1977 and 1980 animated adaptations of J.R.R. Tolkien’s “The Hobbit” and “The Return of the King,” appeared on “The Love Boat,” “One Life to Live,” “The Facts of Life” and “Murder, She Wrote.”

He moved to Venice, Calif., in 1984 where he became an active community member, renovating homes and starring in local plays, including a few appearances at the Odyssey Theatre in West L.A. and 1991’s “Waiting for Phil” at the Richard Burbage Theatre.

In 1993, he published “25 Ways to Cook a Mouse: Whisker Liking Recipes for Your Gourmet Cat” and booked his longest television gig yet. He played Loren Bray, the cynical storekeeper on CBS’ “Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman,” which ran through 1998 before being made into a movie. While most actors would love to land a syndicated series, Bean merely regarded it as his “day job.”

“I love being on my TV show. But I honestly look at it as the day job that enables me to do this [work in the theater], which is where my heart is,” Bean told The Times in 1997. Bean said he’d “rather do theater for nothing than get paid to do my TV show” and he enjoyed the success but “never took it seriously.”

“I made up my mind I was going to walk that thin line between fame and oblivion. The only real benefit of being famous is being recognized by head waiters and getting good tables at restaurants. The rest is part ego trip and part inconvenience. But sure, I love going to Sardi’s and seeing if my picture’s still up — it is — or when people come up and say, ‘I saw you in such and such,’” he told The Times. “Of course, [adulation] is one of the reasons you start doing this. It’s why I stood up in grammar school, made faces and wrote filthy things on the blackboard. But once you get past that, the actual craft is there — and that becomes the fun.”

That credo echoed throughout the remainder of his career as he focused on his craft onstage and peddled whatever merchandise he had to in order to sustain his passion. He passed up a lucrative appearance in the 1980s and 1990s series “MacGyver” because he wanted work on Dario Fo’s political satire, “Accidental Death of an Anarchist,” at the Odyssey. He performed on stages as obscure as the now-closed Richard Basehart Playhouse in Woodland Hills (reviving the 1964 musical “I Was Dancing “in 1993) and as prominent as the Odyssey (“Hess” in 1984 and “Symmes’ Hole” in 1988).

“It’s wrong to make a living off the theater,” he told The Times. “Theater should be supported, like redwood trees. You should make your living — whether you’re a writer or an actor or a director — in movies or commercials. But you do theater out of love. You can always make a living doing the other stuff. I make more than a handsome living doing voices for commercials; I hear myself all day on the tube. Lately, I’m selling Jeep Eagles and Diet 7-Up and Samsonite luggage and La-Z-Boy recliners…. Money is only a problem for those people who decide it’s a problem.”

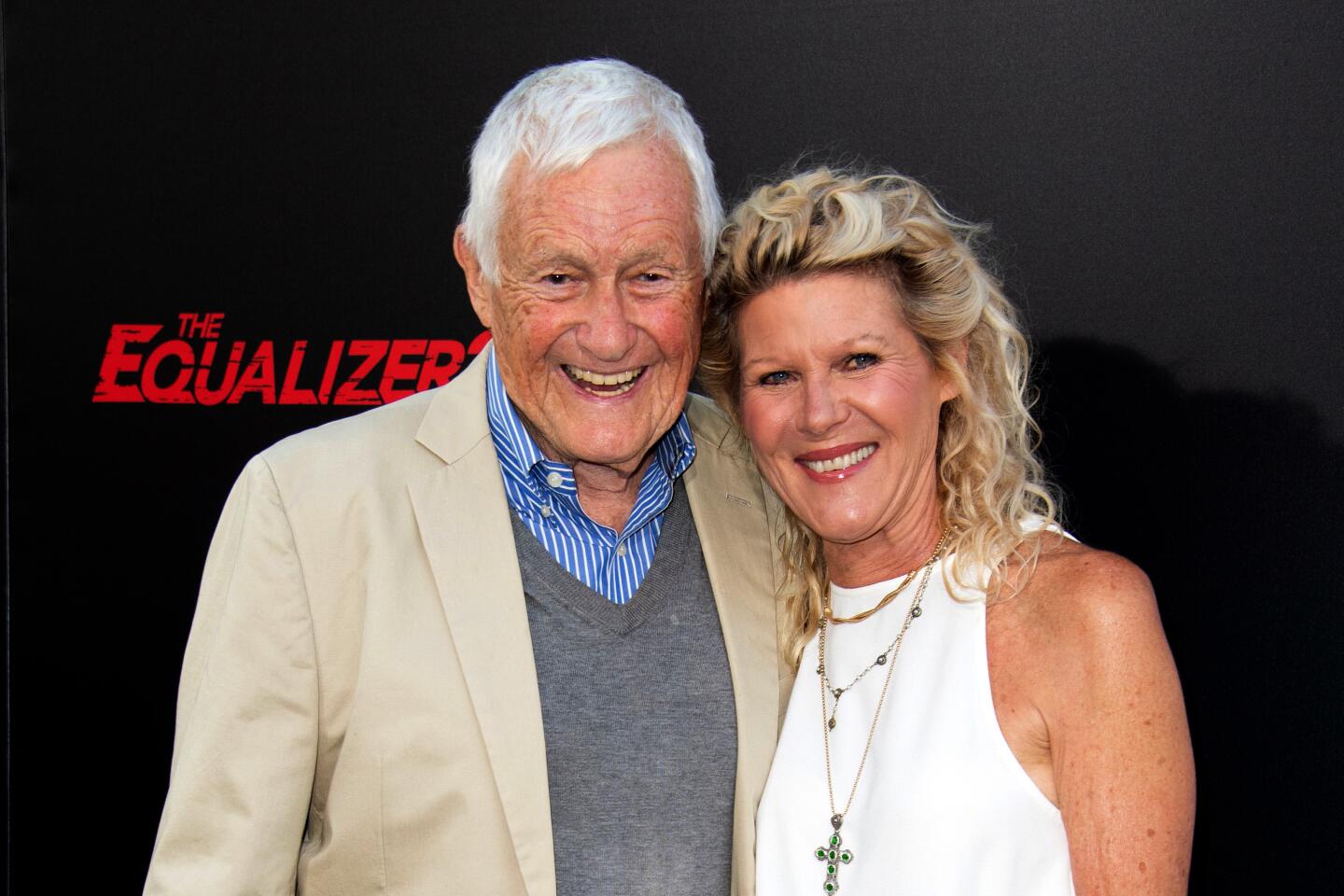

Steering the autobiographical stage show “Alright Then” toward its wrap-up, Orson Bean reaches toward his wife, Alley Mills, and grasps her hand as he announces that what he most wants to tell the audience about is “the miracle — and I do mean miracle — of how on earth you wound up saying yes to me.”

He met his third wife, “Wonder Years” actress Alley Mills, during an evening of play readings for new authors and she played his love interest on “Dr. Quinn.” Mills, 23 years his junior, married him in 1993. The couple settled down in Bean’s homes on the Venice canals, where they were boosters of the community theater scene. He and Mills sat on the board of trustees of the Pacific Resident Theatre, putting on little-produced classic plays and contemporary shows, including “The Quick-Change Room” in 1997, “Candida in 1998 and a free, kid-friendly “Christmas Carol” each year.

“I’m having the time of my life,” he told The Times in 1989 when he appeared in the Odyssey’s “Accidental Death.” “I don’t want to go home when (the show) is over. Sure, it’s work — but it feels like fun. It was much harder 40 years ago. I used to get nervous then. Now, I’ve learned not to make things a problem. I mean, acting is so easy! I love it and I’m good at it. I’m better at it than I was when it was hard. That comes from being 61 years old, and from doing it a lot. Anything that’s done correctly is easy. Not just looks easy, is easy.”

Bean still appeared on the big screen, playing the 105-year-old fool for carrot juice Dr. Lester in Spike Jonze’s 1999 film, “Being John Malkovich” and added several more TV credits to his resume.

Well into his 80s, Bean starred in Steven Drukman’s “Death of the Author” at the Geffen Playhouse in 2014 and headlined his solo show “Safe at Home: An Evening With Orson Bean” at the Pacific Resident Theatre in 2016. The latter play, based on his memoir, recounted his humorous and heart-wrenching life, his 50 years in show business and his determination to be happy.

“Once I understood it was all in the attitude, I stopped worrying about making a living. And the phone always rings--as it always has. I always get a job, as I always have. The only thing that’s left out is the worrying about it,” he told The Times. “And you know, indifference is a great aphrodisiac. If you’re not needy, you get. If you’re overly anxious to have a love relationship, the women stay away in droves . If you’re genuinely indifferent, they’ll follow you anywhere.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.