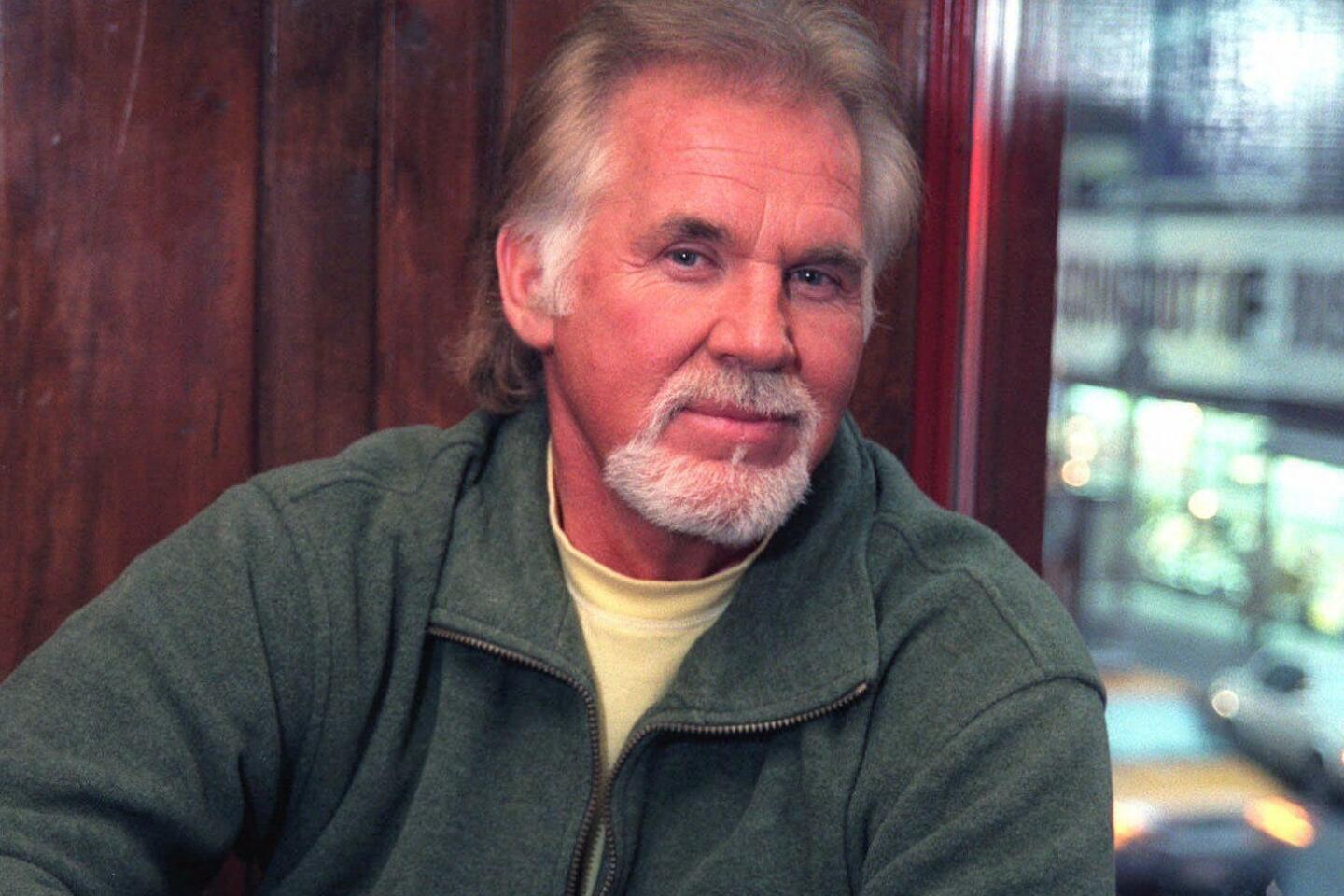

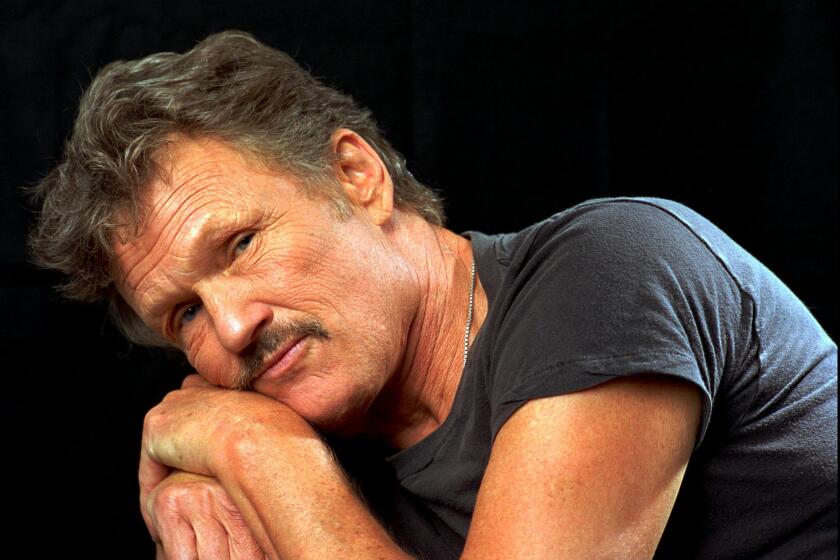

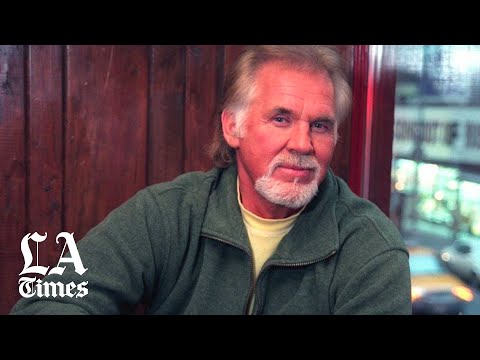

Kenny Rogers, country-pop hitmaker and crossover star, dies at 81

Kenny Rogers was broke, three times divorced and picking out a living as a bass player with a country-rock outfit called “The First Edition” when a sentimental ballad about a lovesick husband rolled onto his lap.

In “Lucille,” Rogers found a comfortable middle ground in the vast stretches between country and pop music, fertile turf that would yield a remarkable string of aching love songs and narrative ballads about gamblers, drifters and lost souls searching for love.

While country music purists balked at his syrupy message-in-a-song ballads, his fans packed arenas that only the titans of rock could fill, his hits climbed the charts and his genial persona and bourbon-smooth voice became a natural fit in America in the 1970s and ‘80s.

Never far from the spotlight, Rogers died Friday of natural causes while in hospice care at his home in Sandy Springs, Ga., said his representative, Keith Hagan. He was 81.

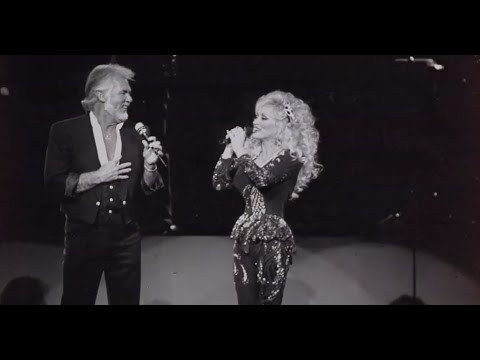

“I loved Kenny with all my heart. My heart’s broken. A big ol’ chunk of it has gone with him today,” Dolly Parton, the musician’s frequent singing partner, said in a video tribute on Twitter.

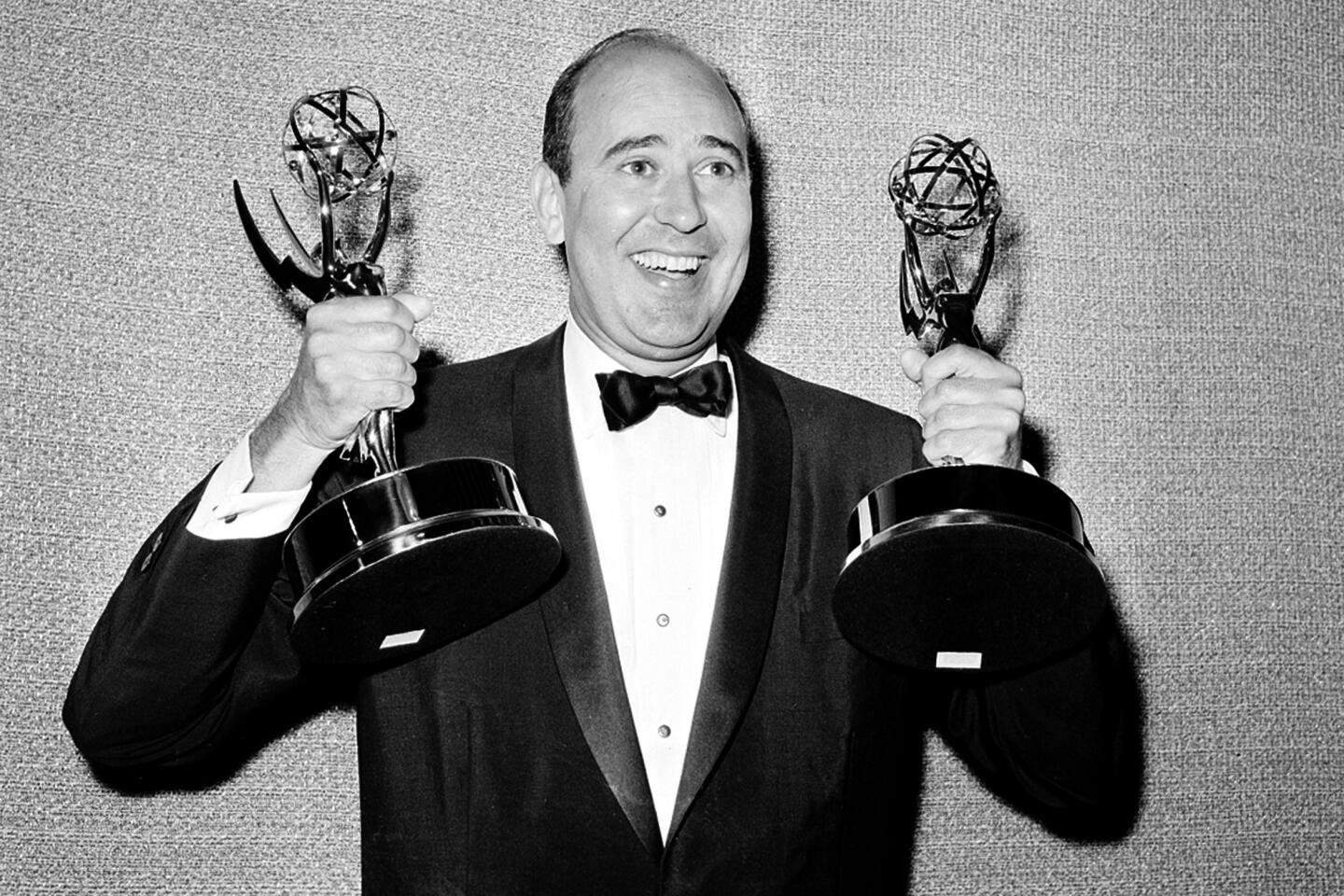

Over the decades, the musical storyteller racked up an impressive catalog of hits — initially as a member of the First Edition starting in the late 1960s and later as a solo artist and duet partner with Parton — and earned three Grammy Awards, 19 nominations and a slew of accolades from country-music awards shows.

Credited with helping to blur the lines between country and pop, Rogers was belatedly inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2013.

“I think part of it is that there’s a certain amount of resentment that I made country go pop, and yet I think it actually added a lot of viewers to it,” Rogers told the Boston Globe that same year. “As you can see now, it’s so much more pop than where I took it.”

Coming up in an era when Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson shaped the heart of the genre, Rogers remained a firm believer that country music was “the white man’s rhythm and blues.”

“It’s where the pain is. And I think, to some extent, I ‘popped’ it so much that it lost some of the pain,” Rogers told CMT in 2012. “I never meant to do that, but on some of the songs through the years, like ‘She Believes in Me’ or ‘You Decorated My Life,’ those are not country country songs.”

Rogers believed he took country music to a mainstream audience, and he was instantly recognized for his signature look: a neatly trimmed beard, a shock of silver hair and flared shirt collars. He modeled his aesthetic after “Grizzly Adams” star Dan Haggerty for a particular reason. When he started out in his first group, the First Edition, he was the oldest member.

“I was three or four years older than all of them,” Rogers said in 2014. “They were looking for someone younger. I let my hair grow, I grew a beard — I got that from Dan Haggerty, the actor who was on TV at the time, and I liked the way he looked. I put an earring in my ear and wore sunglasses. After that, they wanted me with everything they had.”

At the height of his success, Rogers was a staple on the country-music charts, starred in TV movies and even fronted a fast-food chain bearing his name. (Kenny Rogers Roasters was referenced and ridiculed in shows ranging from “Seinfeld” to “Fresh Off the Boat.”) Rogers toed the line between risk-taking artist and crowd-pleasing performer, earning rave reviews from fans but the frequent critical ire of reviewers hoping for a fresh take on his classics.

Kinder reviews of his shows in this newspaper described Rogers “singing with musical understanding, subtlety and warmth” and another calling him “the kind of performer who generates undying, all-accepting love from his listeners.”

His husky voice conveyed the heart-wrenching tales of “Lady’s” knight in shining armor, the advice-dealing “Gambler” and “Lucille’s” lovelorn husband left with four hungry kids and a crop in the fields.

But that success, he repeatedly said, came with a steep price.

“There’s a fine line between being driven and being selfish,” Rogers wrote in his bestselling 2012 memoir, “Luck or Something Like It.”

He admitted to crossing that line many times.

Staying on the road six months at a time without going home during his early marriages was among those selfish acts. He disconnected with his wives and young children, but took responsibility for that later in life.

Upon announcing his initial retirement in 2015, Rogers vowed not to make the same mistake with his twin boys, Justin and Jordan, whom he had with his fifth wife, Wanda Miller. Rogers married Janice Gordon in 1958, who, as the story goes, became pregnant when Rogers lost his virginity at 19. He went on to marry Jean Rogers 1960 (they split in 1963), Margo Anderson in 1964 (they split in 1976), Marianne Gordon in 1977 (they split in 1993) and finally Wanda Miller in 1997.

“Not many people get to see the end of the rainbow, and I think I have,” Rogers said. “I think I’ve had the beauty of this career, and the beauty of getting to know you guys daily out on the road, and watching you kids grow up with me.”

Rogers’ farewell retirement tour, the Gambler’s Last Deal, was cut short in 2018 so that the singer could “work through a series of health challenges.” He had another health scare in May 2019 that landed him in the hospital for dehydration.

“I didn’t want to take forever to retire,” Rogers said in his 2018 statement. “I’ve thoroughly enjoyed this opportunity to say farewell to the fans over the course of the past two years.... I could never properly thank them for the encouragement and support they’ve given me throughout my career and the happiness I’ve experienced as a result of that.”

Kenneth Ray Rogers was born Aug. 21, 1938, in Houston, the fourth of Edward Floyd and Lucille Lois Hester Rogers’ eight children. His heritage was mixed: Irish on his mother’s side and potentially Native American on his father’s because of his grandmother, Della Rogers.

“We were poor people living in the projects, but we didn’t know it because we were all in the same boat,” he wrote of his upbringing in a Houston housing project built in the 1950s.

Though he grew up amid segregation, he said he always liked to think of himself as “color blind” and wrote of memories of friendly faces and people sitting out on their porches.

In high school, he formed his first band — a doo-wop group called the Scholars — and hit the charts young as a solo artist in the late 1950s. He performed “That Crazy Feeling” on Dick Clark’s “American Bandstand” and played standup bass with the Bobby Doyle Three jazz trio. The sound influenced his music, but his mother’s passion for the country sound and listening to it growing up kept him in the country lane.

In 1966, he joined the folk group the New Christy Minstrels; then came the First Edition, which scored its first hit in 1967 with the LSD ode “Just Dropped In (to See What Condition My Condition Was In).” They followed that with “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love To Town,” “Reuben James,” “Something’s Burning” and “Tell It All Brother.” Their success came with a name change, and the band started going by Kenny Rogers and the First Edition.

Rogers left First Edition in 1976, and the rift wasn’t easy for the young singer.

“When the First Edition broke up, it was like my life had just lost all the footing because I was so used to having all these guys behind me…. I think when you walk out there alone, you better be prepared,” Rogers said.

But his solo career soon took off and so did his unique blend of country and pop. The heartbreaking “Lucille” and its vivid storytelling marked his first breakthrough. Written by Roger Bowling and Hal Bynum, the bitter-edged 1977 tune and its corresponding Grammy Award launched him to superstardom.

He followed up his first solo hit with duets with Dottie West (“Daytime Friends,” “Sweet Music Man” and “Love or Something Like It”), followed by his major hits, “The Gambler” and “Coward of the County.” The latter two songs were adapted into TV shows he starred in.

Rogers said that when he first recorded “The Gambler,” written by Don Schlitz, he just thought it was about gambling. But Schlitz wasn’t a gambler and, in fact, wrote the song about his life philosophy. Schlitz simply used gambling as an analogy, yielding the iconic lyrics: “You’ve got to know when to hold ’em / Know when to fold ’em / Know when to walk away / And know when to run.”

“The Gambler” TV movie of 1980, starring Rogers in the western’s title role as Brady Hawkes, spawned four follow-ups and became the longest-running miniseries franchise on television at the time. It forged Rogers’ image as a media perennial — a lovable con man gone good who sang romantic songs.

His version of Lionel Richie’s “Lady” in 1980 was a pivot from the commercial country hits with which he had been identified, according to a 1987 review in The Times. And his decision the same year to release “Gideon,” a relatively uncommercial concept album about the Old West, was even bolder.

His 1983 hit duet with Parton, “Islands in the Stream,” written by the Bee Gees, and the duo’s palpable chemistry cemented Rogers’ lifelong friendship with Parton.

“Everybody always thought we were having an affair. We didn’t. We just teased each other and flirted with each other for 30 years,” he said on HuffPost live in 2013. “It keeps a lot of tension there.”

Rogers reunited with Parton in 2013 for “You Can’t Make Old Friends,” a poignant duet that celebrated their decades-long bond and the title track from his studio album that year.

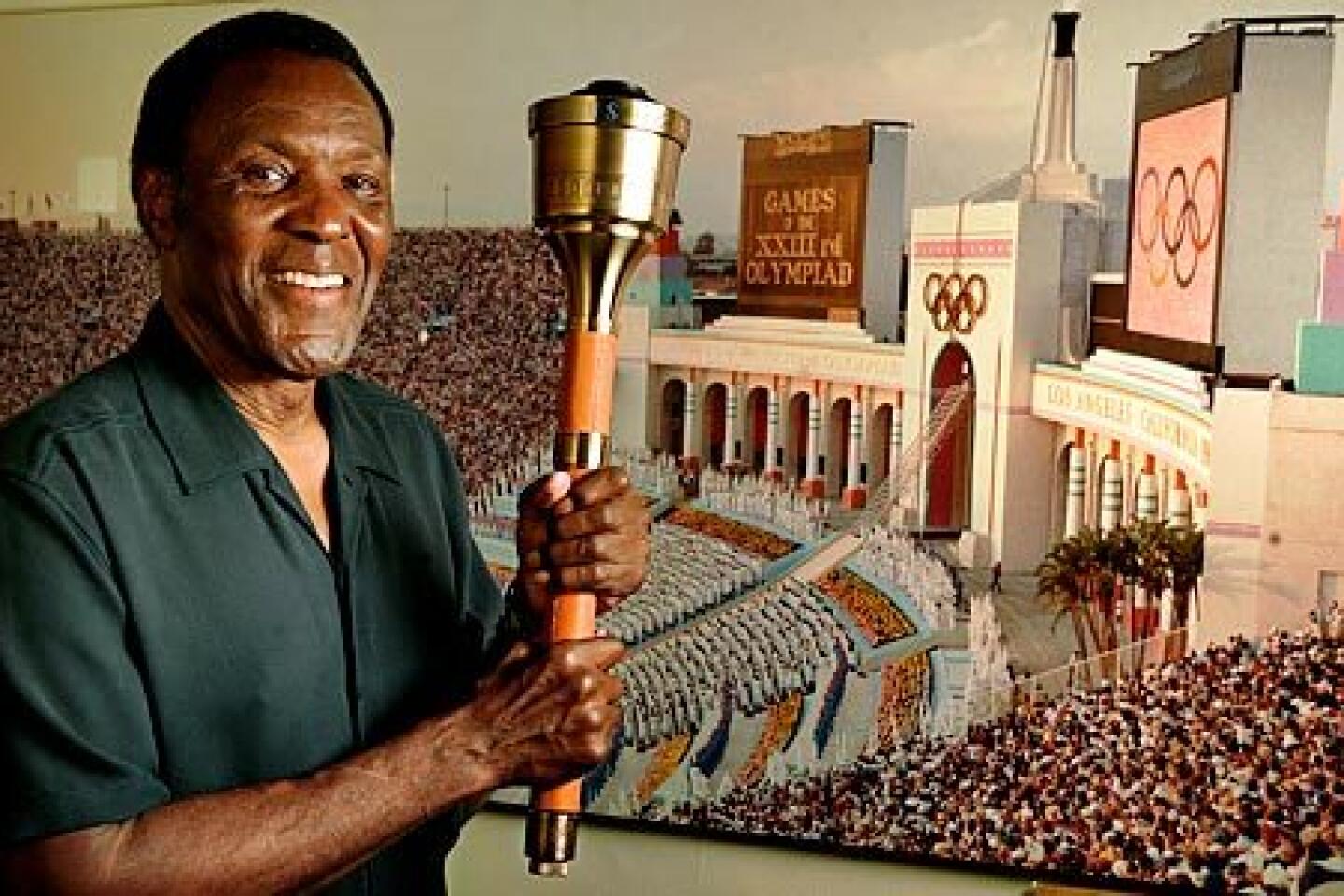

Rogers was among the artists who participated in the 1985 recording of “We Are the World,” raising millions of dollars for famine relief in Africa. The following year, he co-chaired the embattled “Hands Across America” fundraiser and also had an operation to remove a cyst from his vocal cords.

By 1998, Rogers’ stream of steady hits waned and he launched his Dreamcatcher label with Jim Mazza. The move marked a major career comeback and saw him revisit the top of the charts with 1999’s “The Greatest,” which he followed up with “Buy Me a Rose.” But in 2001, the label immersed him in a legal showdown with his longtime manager, Ken Kragen, who shepherded the careers of Richie, Trisha Yearwood and Travis Tritt.

Other side projects that kept the singer active were tennis and photography. He shot a portrait of then-First Lady Hillary Clinton at the White House and in 2014 was awarded an honorary masters of photography from the Professional Photographers of America.

Rogers also released books of his photos, wrote several short stories and appeared off-Broadway in the Christmas musical “The Toy Shoppe.” The Christmas theme continued with the 2015 release of his “Once Again It’s Christmas” album, which featured fellow country stars Alison Krauss and Jennifer Nettles, among others.

Relishing an unlikely renaissance late in his career, Rogers played to younger generations when he appeared at rock-centric music festivals such as Bonnaroo (2012) and Glastonbury (2013) — and to rave reviews, much to his surprise.

“I’m firmly convinced that at this point in my career, my audience falls into one of two categories: either people born since the ’80s whose parents forced them to listen to my music as [a form of] child abuse, or people who were born before the ’60s and can no longer remember the ’60s,” he told the Boston Globe in 2013.

Rogers is survived by his wife Wanda and five children, Kenny Jr., Christopher, Justin, Jordan and Carole.

Times staff writers James Reed and Steve Marble contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.