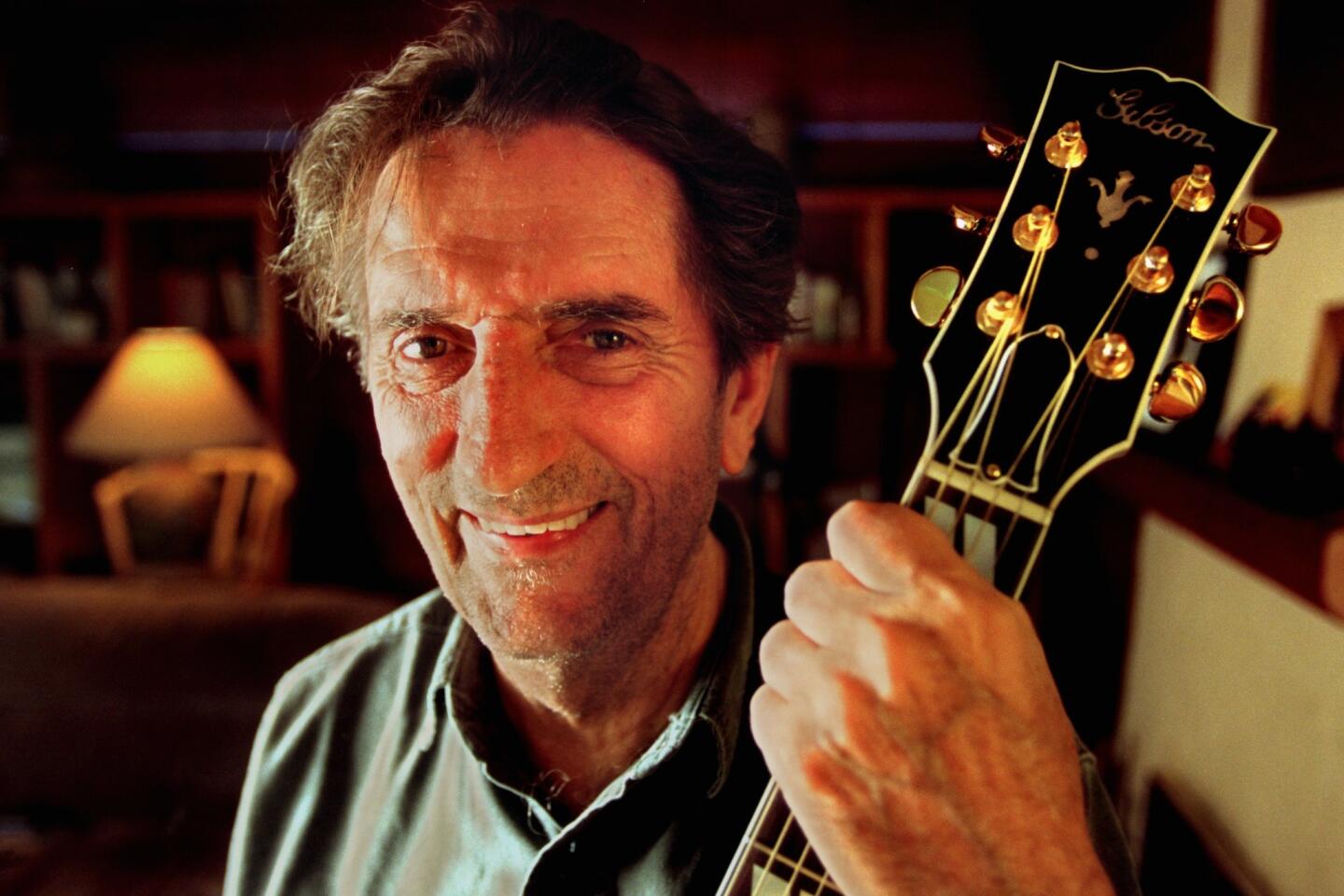

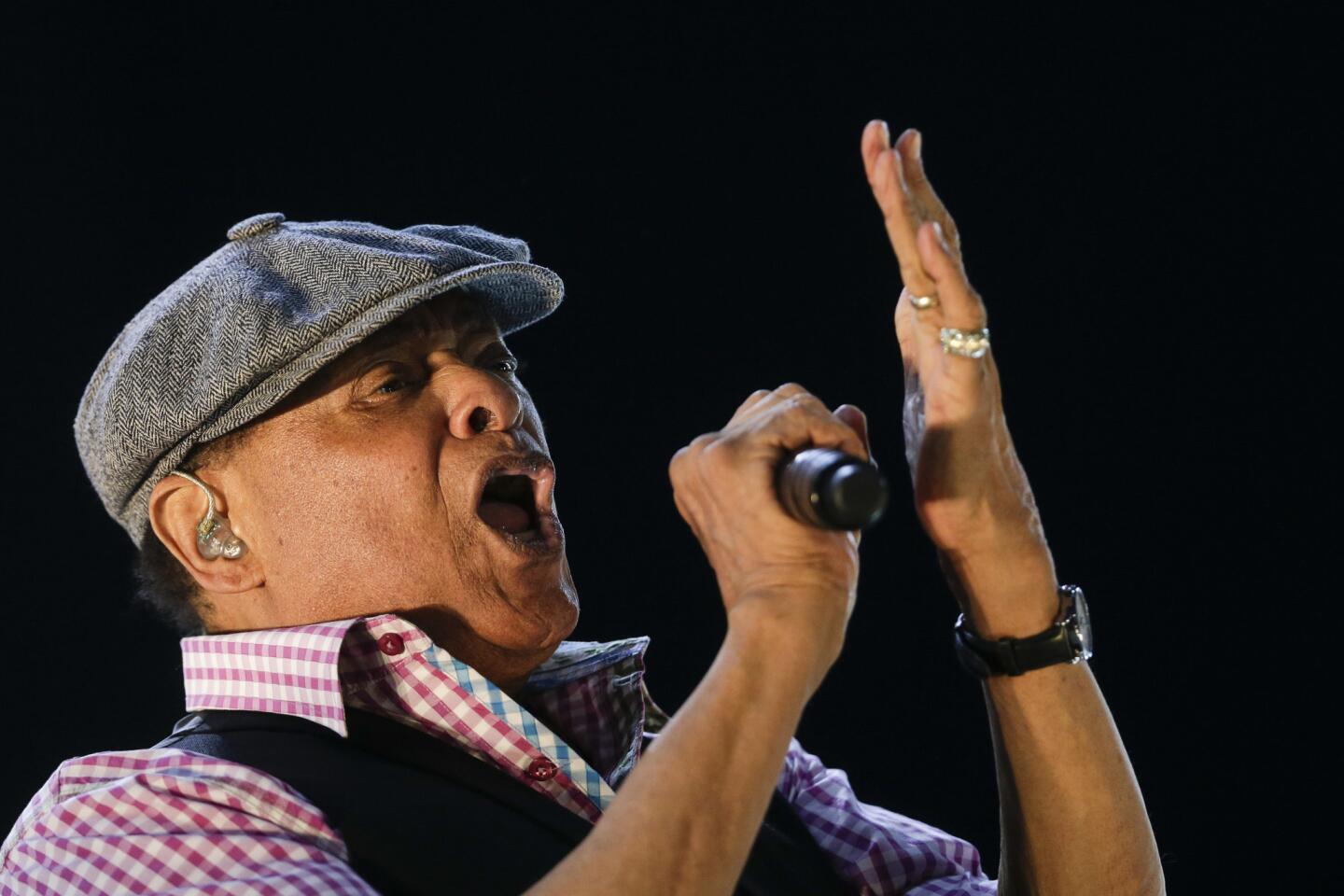

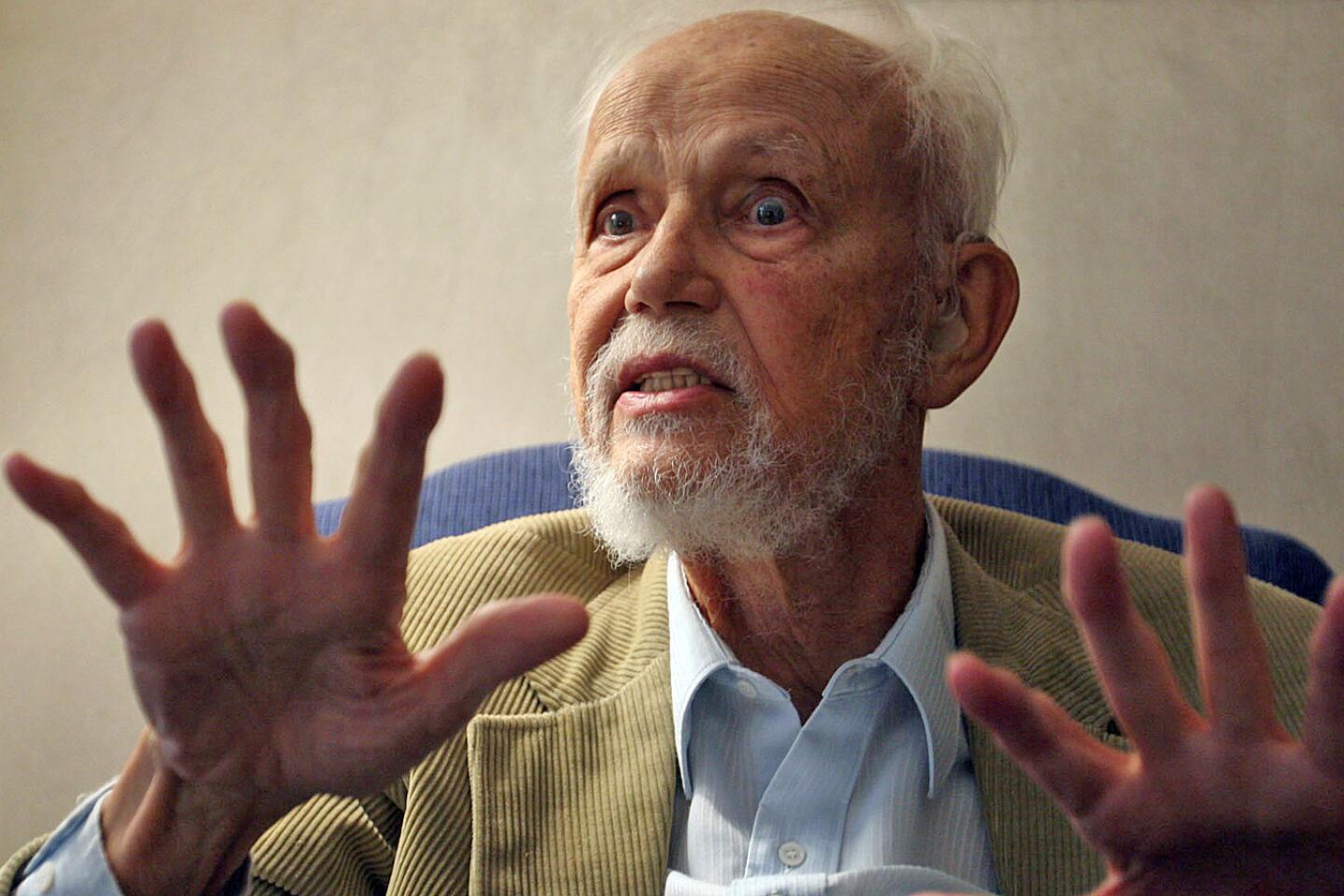

Shelley Berman, who tapped into the neuroses and frustrations of post-World War II America and brought an actor’s sensibility to his monologues to become one of the top comedians of the late 1950s and early ’60s, died Friday at his home near Thousand Oaks.

Berman, who acted throughout his career and had a late career resurgence when he played Larry David’s father on the hit HBO comedy series “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” died of complications from Alzheimer’s disease, according to spokesman Glenn Schwartz. He was 92.

For the record:

11:40 p.m. Nov. 24, 2024The headline on an earlier version of this story said Berman died at the age of 91. He was 92.

The Chicago-born Berman, who came to stand-up comedy via the theater and Chicago’s improvisational Compass Players, defied stand-up comedy convention: He did his act sitting down.

Perched on a bar stool, Berman did not deliver a string of jokes. Instead, he was known for acting out small, angst-filled vignettes, portraying “a man in agony over modern life — over his own life,” as Gerald Nachman wrote in the book “Seriously Funny: The Rebel Comedians of the 1950s and 1960s.” His routines helped pave the way for Woody Allen, Jerry Seinfeld and Bob Newhart, comedians who built their acts around the frustrations of everyday life.

Describing Berman as the “founding father of the school of persecuted comedians — the first of the method comics,” Nachman said Berman “appeared in good mental health, in his sober dark suit and neatly barbered facade, but he sounded like he might unravel at any moment.”

In one classic routine, about the safety of flying, Berman tells the flight attendant who is offering him a pillow, “Oh, Miss, the wing is on fire out there.”

“Oh, really?” she says.

“Yes, really. Take a look out there. The wing is a sheet of flame. Take a look.”

“Coffee, tea, or milk?” she airily responds.

“We don’t have time for coffee, tea, or milk. We’re doomed!”

“Well, then, how about a martini?”

Berman, the neurotic Comedic Everyman — or “Everymanic-depressive,” as Time magazine called him in a 1961 story — was best-known for his telephone routines, the phone always mimed with his hand, never a prop.

In one of them, he portrays an increasingly frustrated office worker who phones the department store across the street to report a woman hanging from a window ledge about 10 flights up:

“Describe her? What for? I’m looking at the building right now; she’s the only one hanging out of a window.”

The phone routines, which predated those of Newhart on the national scene, grew out of Berman’s days doing improvisations with the Compass Players, a precursor to Second City.

“I couldn’t find a partner to work with one night,” he once explained, “so I simply used the telephone.”

1/46

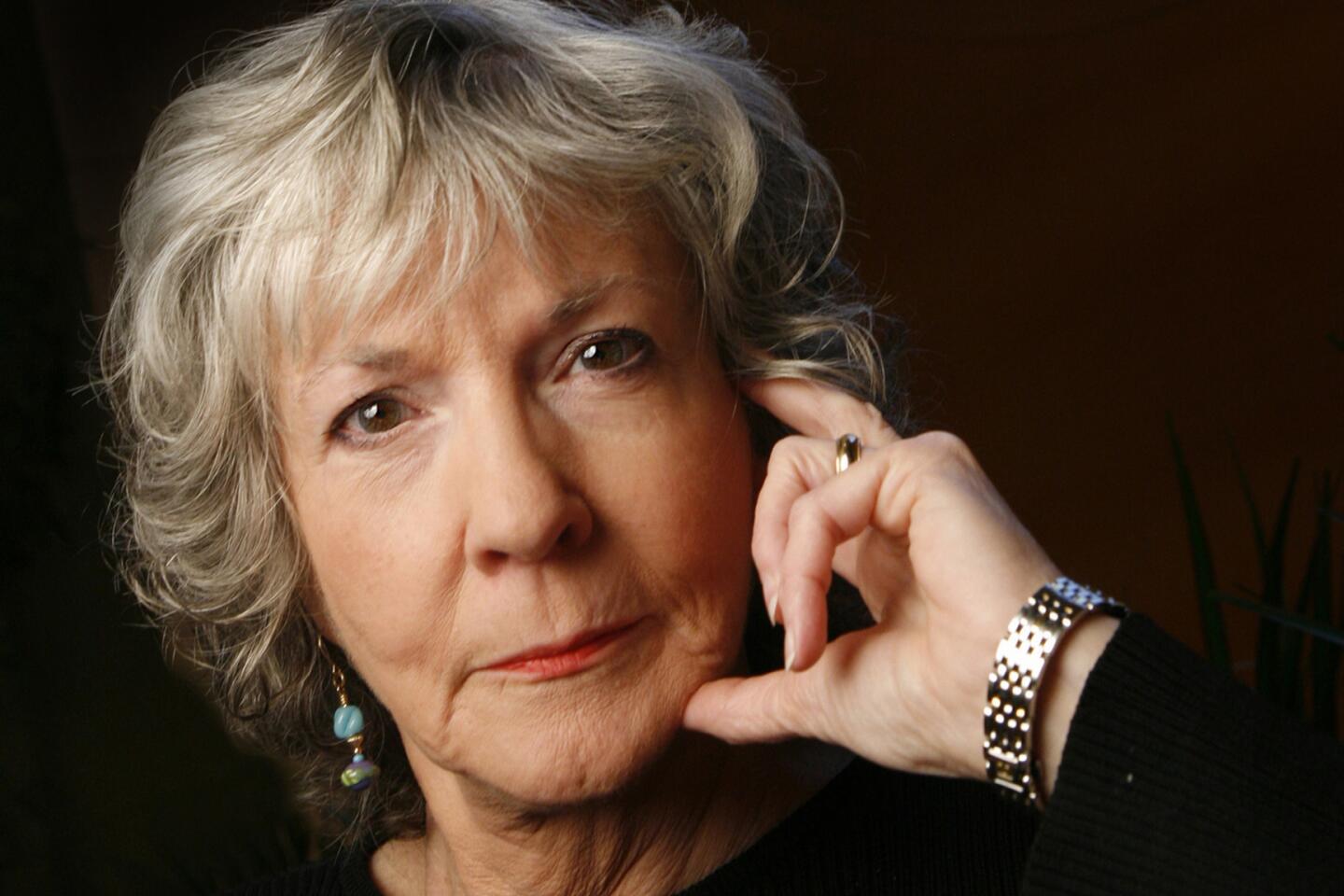

The Santa Barbara writer created one of the first modern hard-boiled female private eyes and topped bestseller lists for decades, inspiring loyal readers to name their daughters after the series’ heroine, Kinsey Millhone. She was 77. Full obituary

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 2/46

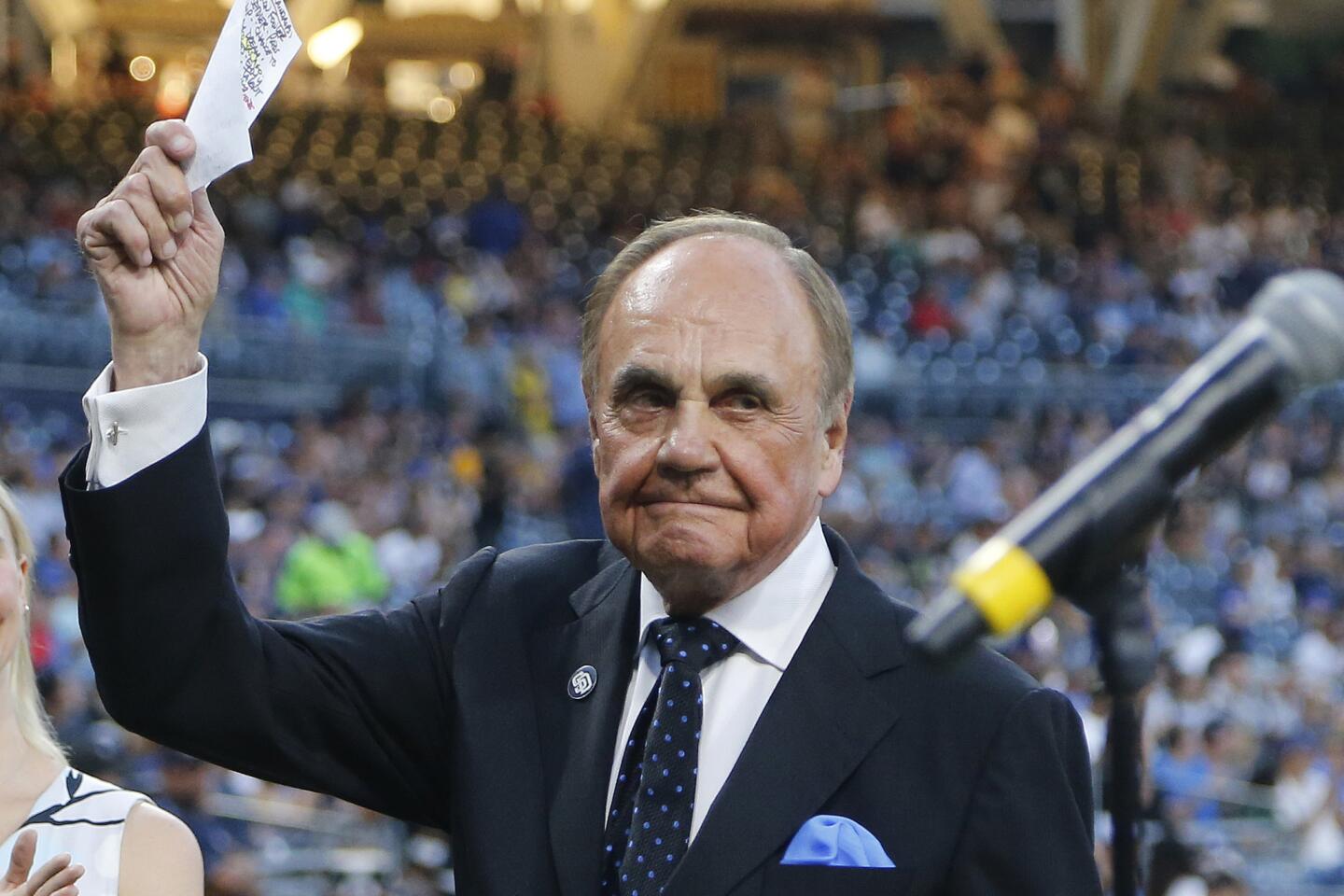

The veteran sports broadcaster was long recognized as one of the most versatile and perhaps most enthusiastic announcers of his era. He also was an author, a longtime fixture at Pasadena’s Rose Parade, the host of several sports-themed TV game shows and was still calling San Diego Padres baseball games in his later years. He was 82. Full obituary

(Lenny Ignelzi / Associated Press) 3/46

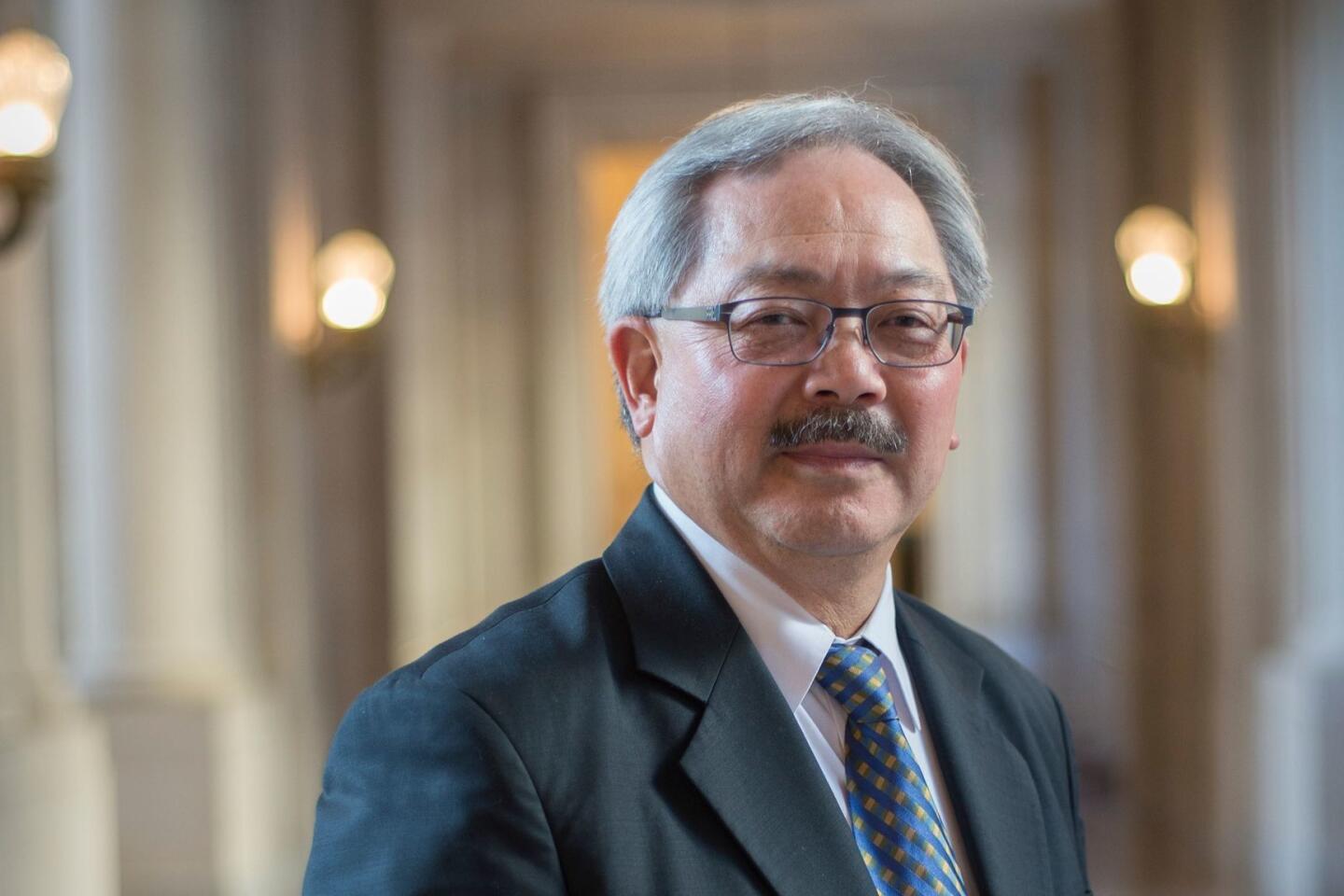

Lee, elected in 2011, was the first Chinese American mayor of San Francisco, home to the oldest Chinatown in the United States. He oversaw years of dramatic growth that transformed the city’s skyline while also sending real estate values to stratospheric levels. He was 65. Full obituary

(David Butow / For The Times) 4/46

The singer and actor became a TV icon in the 1960s playing the lovably naïve Gomer Pyle on “The Andy Griffith Show” and the spinoff series “Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C.” He was 87. Full obituary

(CBS Photo Archive / Getty Images) 5/46

Called “the Elvis of Opera” and the “Siberian Express” by some, Hvorostovsky was known for his velvety baritone voice, dashing looks and shock of flowing white hair. He was 55. Full obituary

(Shiho Fukada / Associated Press) 6/46

The syndicated gossip columnist’s mixture of banter, barbs, and bon mots about the glitterati helped her climb the A-list as high as many of the celebrities she covered. She was 94. Full obituary

(Stephen Chernin / Associated Press) 7/46

The fashion iconoclast’s clingy styles helped define the 1980s. Naomi Campbell was a favored model, and Michelle Obama wore his designs as U.S. first lady. He was 77. Full obituary

(Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times) 8/46

Kaji was the founding president of the Japanese American National Museum, established in 1992 in Little Tokyo. Years earlier, he established his own accounting firm and was part of a group that founded Merit Savings & Loan, one of the first and one of the few Japanese American-owned banks. He was 91. Full obituary

(Edward Ornelas / Los Angeles Times) 9/46

As one of the founding fathers of rock ’n’ roll, Fats Domino blazed a singular path in the history of popular music. Pounding a piano and booming in a baritone both warm and conversational, he gave the nascent genre a shot of rhythm and blues, jazz and boogie woogie from his native New Orleans. He was 89. Full obituary

(AFP / Getty Images) 10/46

Best known for his portrayal of the sharp-tongued butler in the TV sitcoms “Soap” and “Benson,” Guillaume also played Nathan Detroit in the first all-black version of “Guys and Dolls” and became the first African American to sing the title role in “The Phantom of the Opera,” appearing with an otherwise all-white cast in Los Angeles. He was 89. Full obituary

(Ann Johansson / For The Times) 11/46

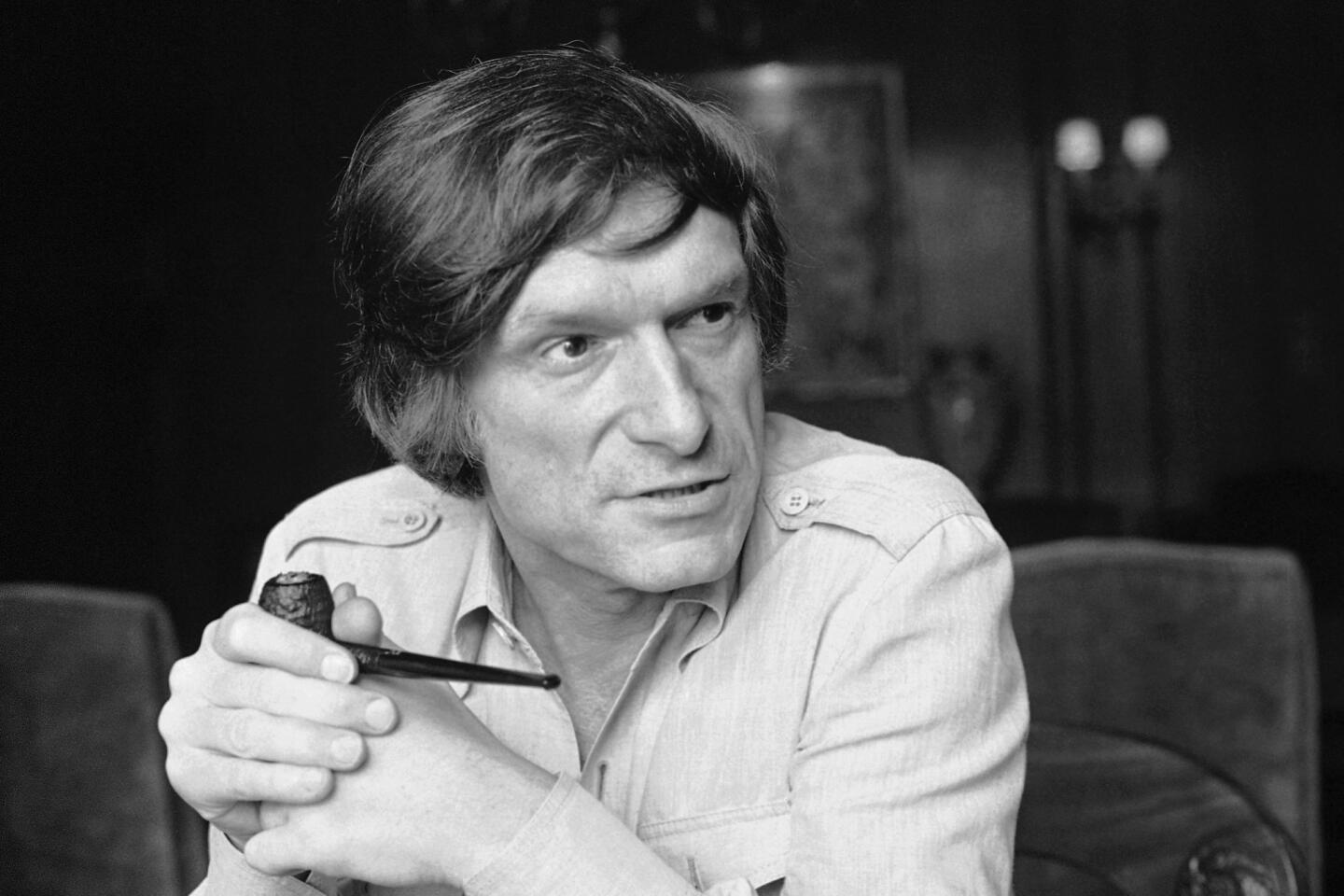

Hefner built a publishing and entertainment empire on the idea that Americans should shed their puritanical hang-ups and enjoy sex. As the founder of Playboy magazine, he pitched an alternative standard — swinging singlehood — which portrayed the desire for sex as being as normal as craving apple pie. He was 91. Full obituary

(George Brich / Associated Press) 12/46

The prolific character actor and occasional leading man brought a soulful, hangdog presence to such varied films as “Alien,” “Paris, Texas,” “Repo Man” and “Pretty in Pink,” becoming a favorite of film fans and directors alike. He was 91. Full obituary

(Richard Derk / Los Angeles Times) 13/46

The gay rights pioneer brought a Supreme Court case that struck down parts of a federal law that banned same-sex marriage and led to federal recognition for gay spouses. She was 88. Full obituary

(Richard Drew / Associated Press) 14/46

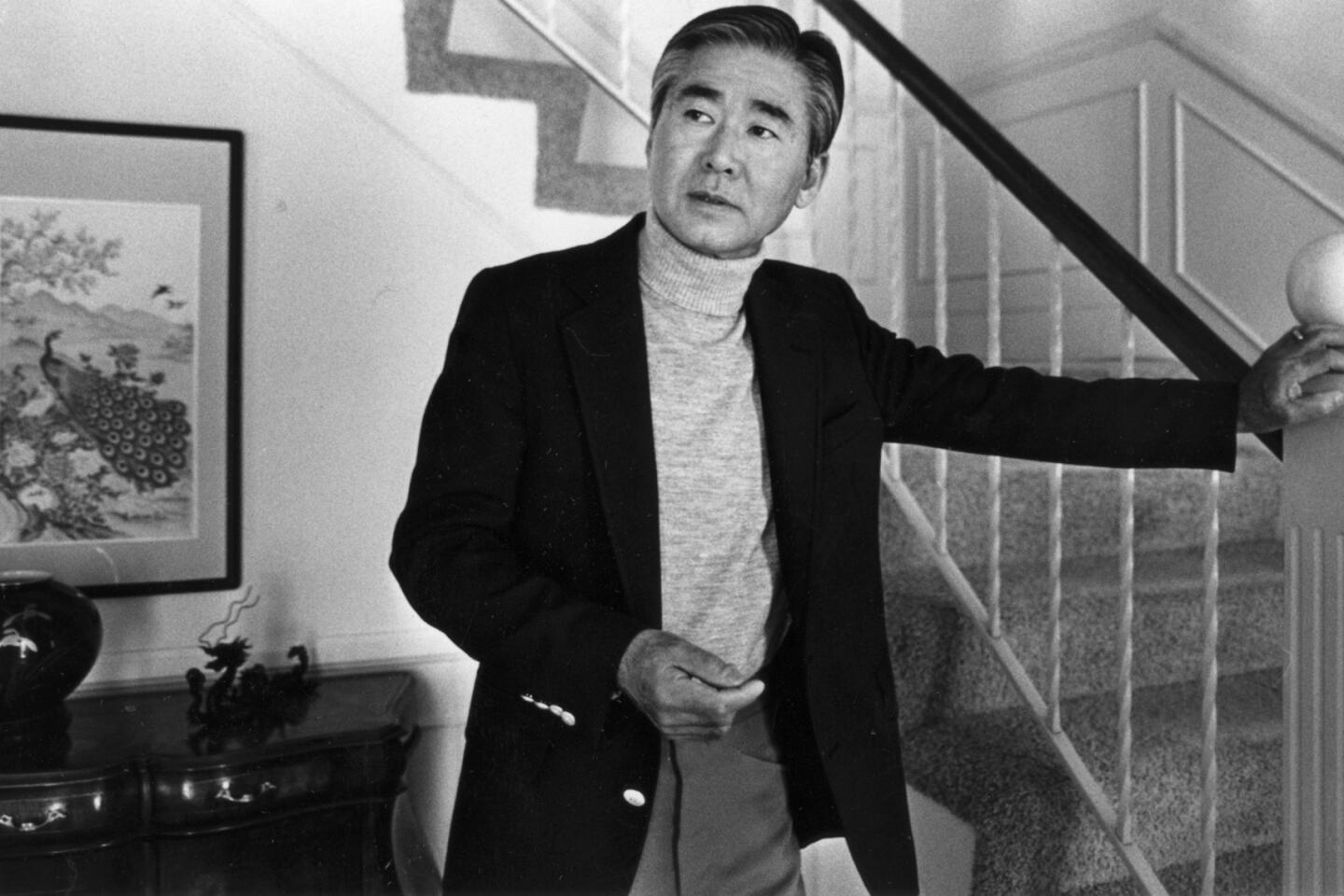

Stomping over miniature bridges and buildings in a rubber suit, Nakajima portrayed Godzilla, the fire-breathing, screeching monster that became Japan’s star cultural export and an enduring symbol of the pathos and destruction of the Atomic Age. Nakajima said he invented the character from scratch, and developed it by going to a zoo to study how elephants and bears moved. He was 88. Full obituary

(Junji Kurokawa / Associated Press) 15/46

Kanno spent what should have been his final high school years confined to a World War II-era internment camp. He went on to become one of America’s first Japanese American mayors as an early-day politician in Orange County. He was 91. Full obituary

(Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times) 16/46

Romero will be remembered best for co-writing and directing “Night of the Living Dead.” The “Living Dead” franchise went on to create a subgenre of horror movies whose influence across the decades has endured, seen in films like “The Purge” and TV shows such as “The Walking Dead.” He was 77. Full obituary

(Amy Sancetta / Associated Press) 17/46

The Oscar-winning actor appeared in classic films such as Alfred Hitchcock’s “North By Northwest” and starred in the “Mission: Impossible” television series in the 1960s. He won his Academy Award for his portrayal of washed-up Bela Lugosi in Tim Burton’s “Ed Wood.” He was 89. Full obituary

(CBS Photo Archive / CBS via Getty Images) 18/46

The French survivor of Nazi concentration camps and a European Parliament president was one of France’s most prominent female politicians. She was best known in France for leading the heated battle to legalize abortion in the 1970s. France’s abortion rights law is still known four decades later as the “Loi Veil.” She was 89. Full obituary

(AFP / Getty Images) 19/46

The British author created Paddington Bear, the marmalade-loving teddy in a duffel coat and floppy hat. His creation become an icon immortalized in print, on screens and as countless stuffed toys. Bond was 91. Full obituary

(Sang Tan / Associated Press) 20/46

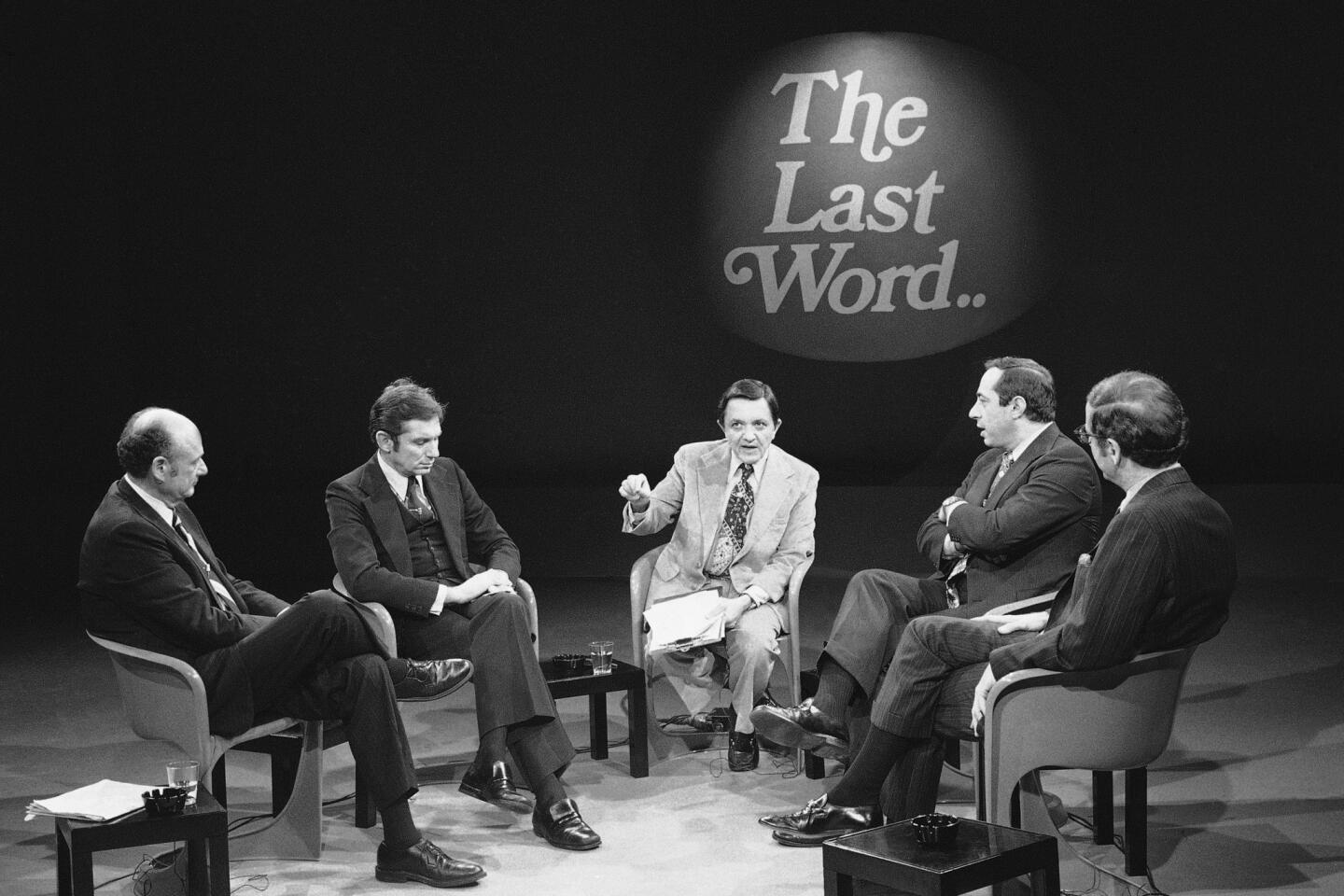

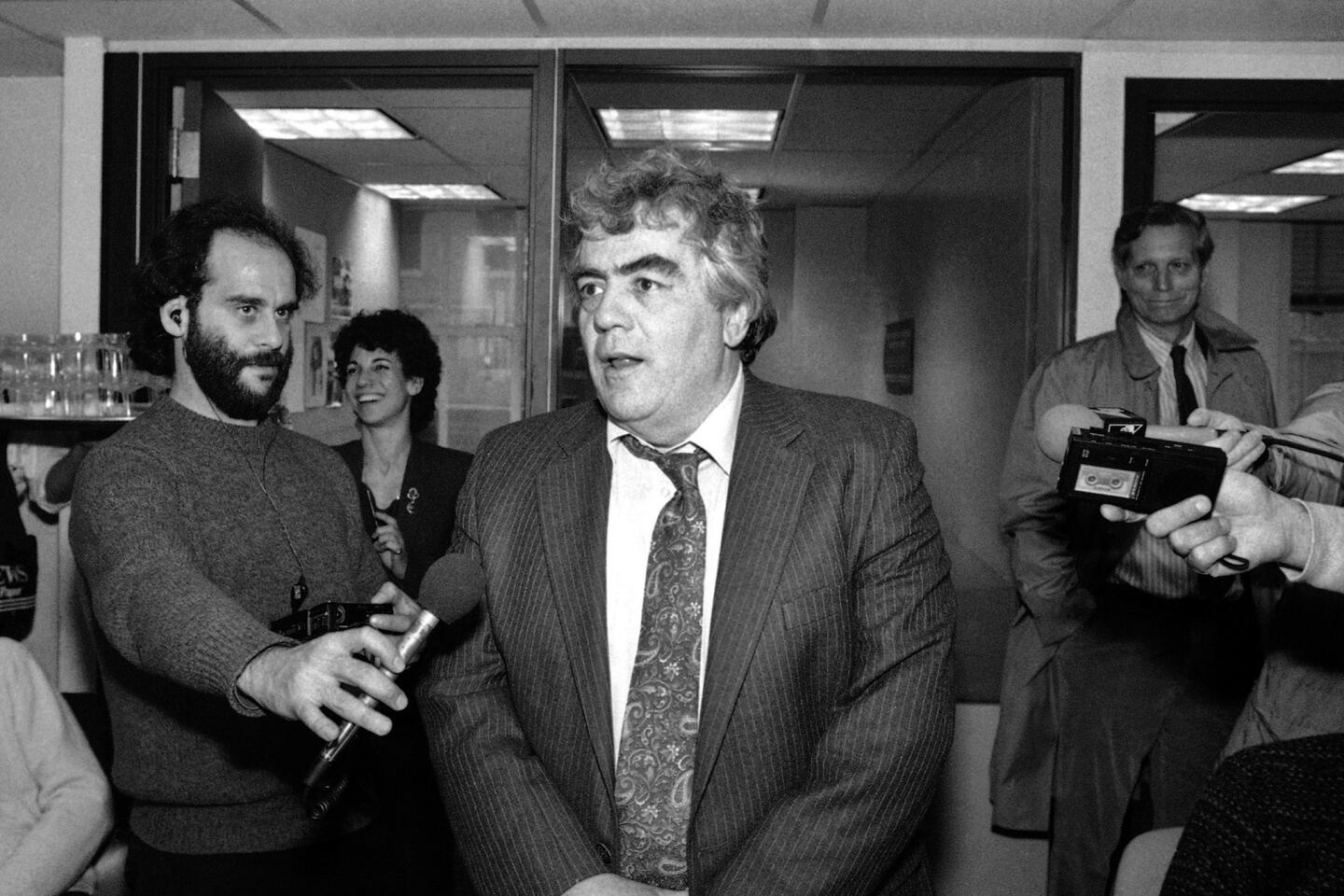

Pressman, center, was an Emmy-winning journalist who worked at WNBC for more than 50 years after stints at New Jersey’s Newark Evening News and the New York World Telegram and Sun. He covered the 1956 sinking of the Italian ocean liner Andrea Doria, riots at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, the Woodstock festival in 1969 and the terror attacks on Sept. 11, 2001. He was 93. Full obituary

(Ron Frehm / Associated Press) 21/46

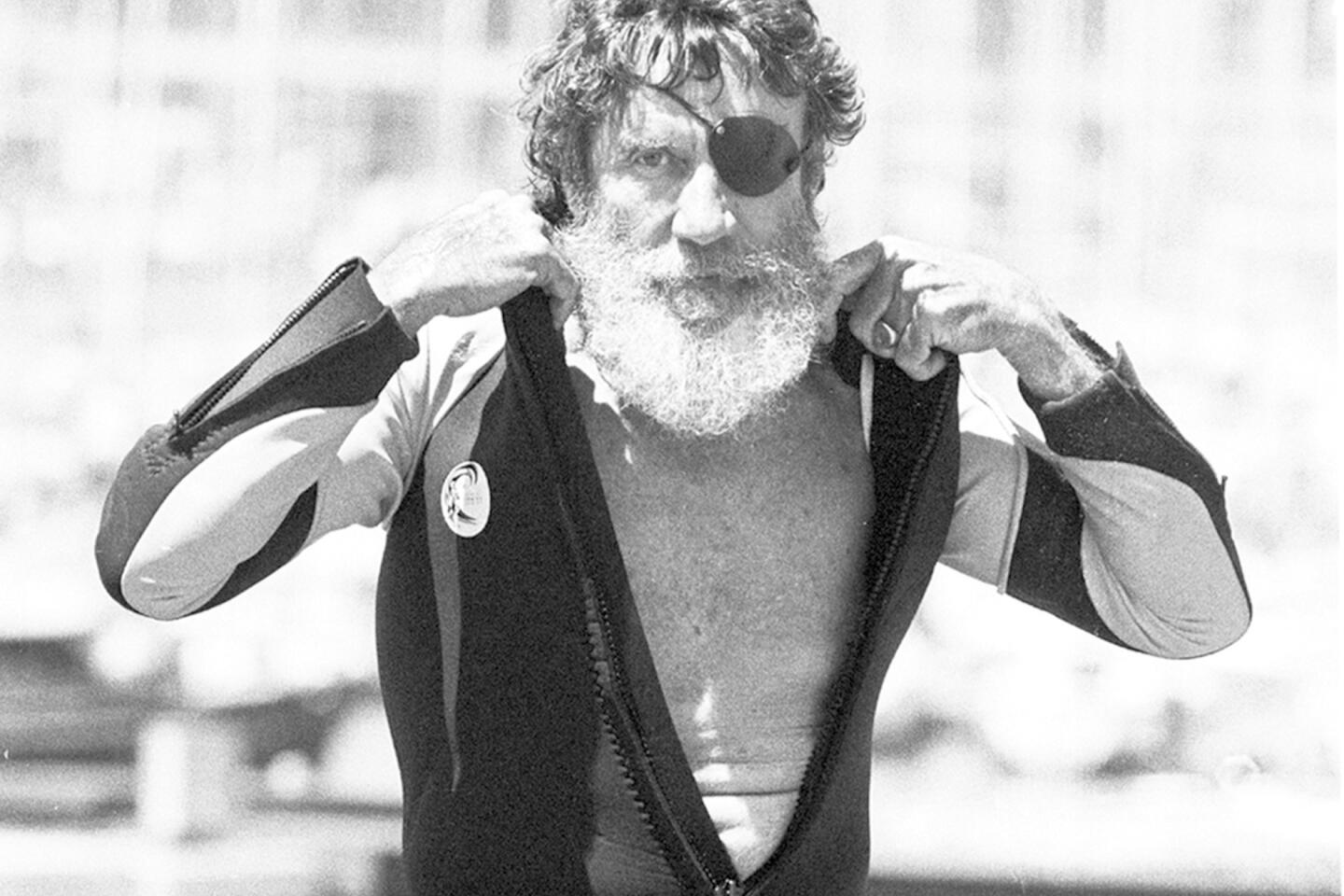

The Santa Cruz entrepreneur opened one of the world’s first surf shops and pioneered the neoprene wetsuit that helped popularize year-round cold-water surfing. He lost his eye in a surfing accident. He was 94. Full obituary

(Dan Coyro / Associated Press) 22/46

The former dictator of Panama often played opposing sides of Cold War-era political battles until he was ousted by his on-again, off-again sponsors and toppled in a U.S. invasion. He was 83. Full obituary

(AFP / Getty Images) 23/46

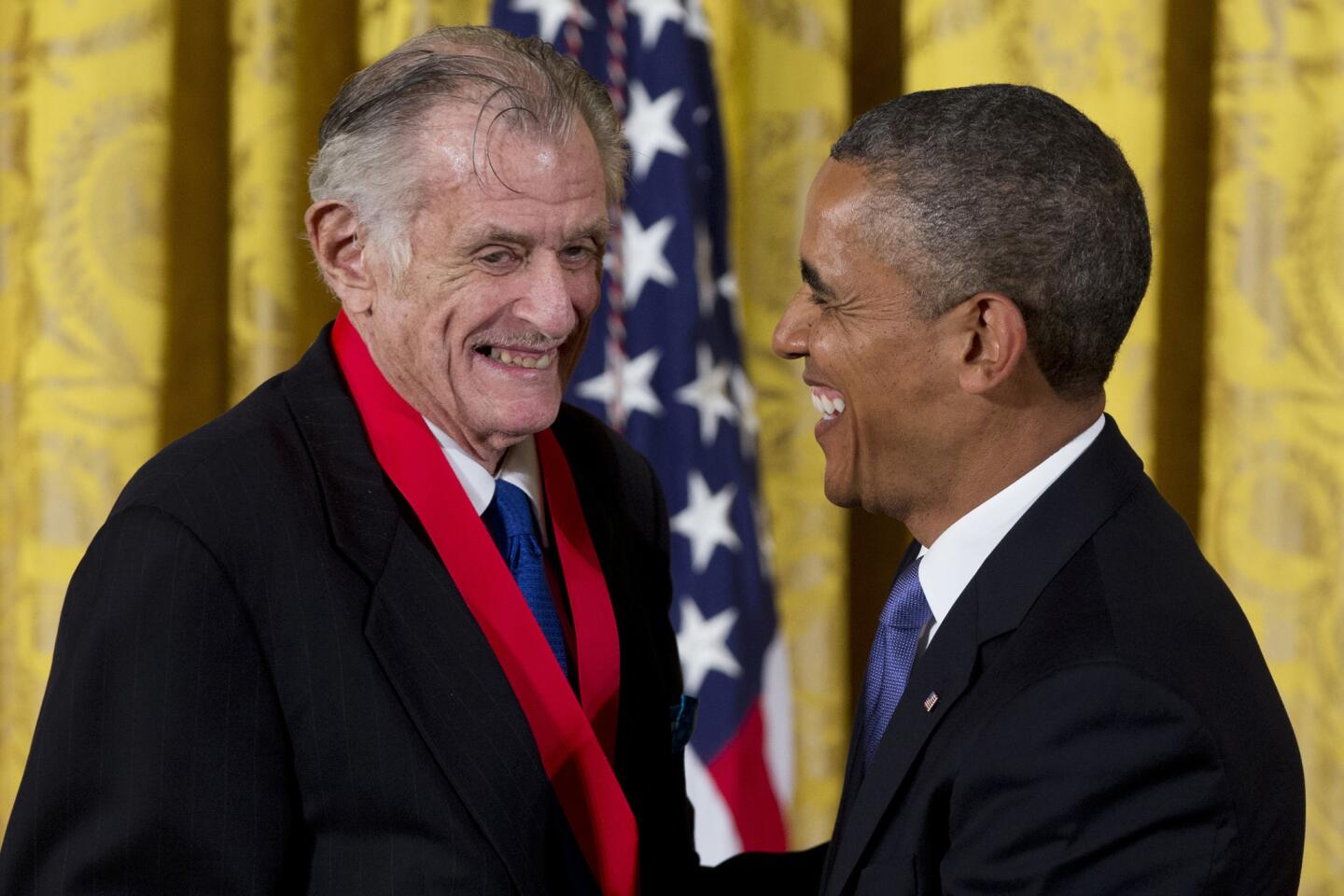

Deford was an award-winning sports journalist and commentator whose elegant reportage was a staple for years at Sports Illustrated and National Public Radio. He was the first sportswriter awarded the National Humanities Medal. In 2013, President Obama honored him for “transforming how we think about sports.” He was 78. Full obituary

(Carolyn Kaster / AP) 24/46

Perenchio deftly pulled the levers of power to create culturally defining media events, propel political candidates, collect masterpiece artworks and become one of the richest men in Los Angeles. In late 2014, he announced that he would leave much of his collection — at least 47 works valued at more than $500 million — to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. He was 86. Full obituary

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times) 25/46

The polarizing Fox News founder was credited with turning the news channel into a ratings powerhouse over his 20 years at the helm. He was ousted from the network following sexual harassment charges. He was 77. Full obituary

(Jennifer S. Altman / For The Times) 26/46

The former child star played Joanie Cunningham in the sitcoms “Happy Days” and “Joanie Loves Chachi.” Her more recent credits included “The Love Boat” and “Murder, She Wrote.” She was 56. Full obituary

(Wally Fong / Associated Press) 27/46

Using insult as his weapon of choice and a quick, knowing smirk as his defense, Rickles delighted audiences with his brand of aggressively caustic humor that targeted everyone from unknown “hockey pucks” to big-name celebrities. He was 90. Full obituary

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 28/46

A close confidante of Nelson Mandela, Kathrada dedicated his life to opposing apartheid and racism. An African National Congress activist, he played a major role in South Africa’s liberation struggle. He was 87. Full obituary

(Kopano Tlape / EPA) 29/46

The billionaire businessman and philanthropist was the last in his generation of one of the country’s most famously philanthropic families. He was 101. Full obituary

(D. Pickoff / Associated Press) 30/46

The Pulitzer Prize-winning newspaper columnist was part of the wave of practitioners of what came to be known as New Journalism: a group of gifted writers that included Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, Hunter S. Thompson, Joan Didion and others who reported on the social and cultural upheavals of the 1960s and ’70s. His writing made him a New York City institution for more than 40 years. He was 88. Full obituary

(Mario Cabrera / Associated Press) 31/46

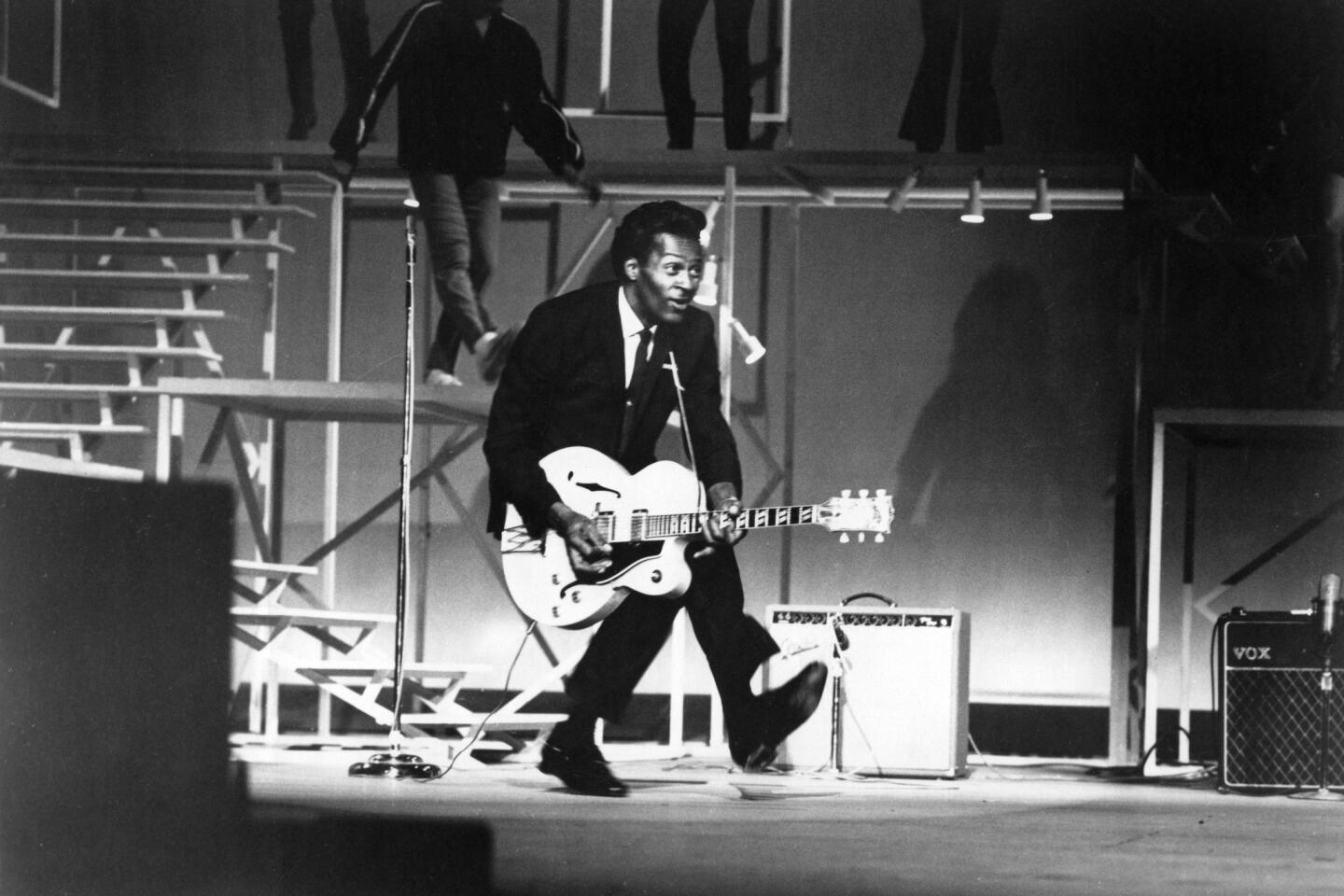

One of the founding fathers of rock ’n’ roll, Berry was an innovator who designed much of the music’s sonic blueprint and became his era’s most creative lyricist. He was 90. Full obituary

(Michael Ochs Archives / Getty Images) 32/46

The Nobel-prize winning poet was known for capturing the essence of his native Caribbean. His work was widely praised for its depth and bold use of metaphor, and its mix of sensuousness and technical prowess. He was 87. Full obituary

(Berenice Bautista / Associated Press) 33/46

The Boxing Hall of Fame trainer and manager handled the careers of 19 champions including heavyweight Evander Holyfield. Duva with his family built the promotional company Main Events into one of boxing’s powerhouses. He was 94. Full obituary

(Mike Groll / Associated Press) 34/46

The silver-haired and dapper Osborne was a bona fide movie connoisseur who displayed his wide knowledge of films as the genial host on Turner Classic Movies since its launch in 1994. Osborne was a longtime columnist for the Hollywood Reporter and the “official biographer” of the Academy Awards. He was 84. Full obituary

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 35/46

Dubbed the “Acrobat of Scat” for his vocal delivery, Jarreau was admired by fans for his imaginative and improvisational qualities. He is best known for his single “We’re in This Love Together” from 1981. He is the only Grammy vocalist to win in the jazz, pop and R&B categories. He was 76. Full obituary

(Felipe Dana / Associated Press) 36/46

Mansfield won the Nobel Prize for helping to invent MRI scanners. In 1978, he was the first person to step inside a whole-body MRI scanner so it could be tested on a human subject. His work, alongside chemist Paul Lauterbur, revolutionized the detection of disease by revealing internal organs without the need for surgery. He was 83. Full obituary

(David Jones / Associated Press) 37/46

Riva’s portrayal of an elderly woman in the 2012 end-of-life drama “Amour” earned her international acclaim and the distinction of being the oldest nominee for a lead actress Oscar. She was 89. Full obituary

(Francois Mori / Associated Press) 38/46

Moore rose to stardom on “The Dick Van Dyke Show” in the 1960s and went on to headline “The Mary Tyler Moore Show,” a highly successful sitcom in the 1970s (pictured). The actress and her television character became so entwined that Moore became a role model for women who sought to challenge the conventions of marriage and family. She was 80. Full obituary

(CBS Photo Archive / Getty Images) 39/46

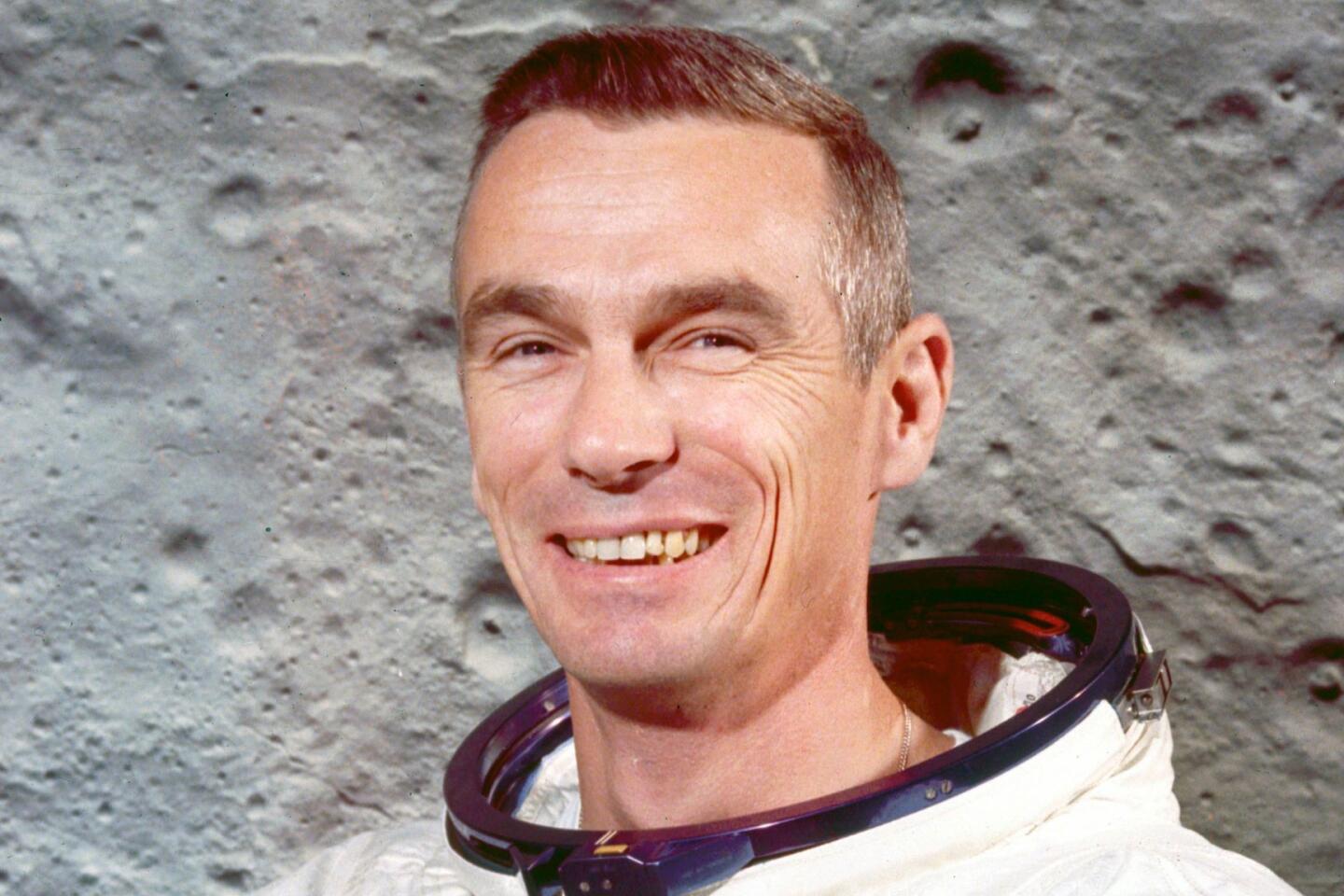

Cernan, commander of NASA’s Apollo 17 mission, set foot on the moon in December 1972 during his third space flight. He was the last of only a dozen men to walk on the moon. He returned to Earth with a message of “peace and hope for all mankind.” He died at 82. Full obituary

(SSPL / Getty Images) 40/46

The former California state librarian wrote rich cultural, economic and political histories on the birth, growth and maturation of the Golden State. He captured the state’s rise in influence and its singular hold on the public imagination in his sweeping “Americans and the California Dream” series. Full obituary

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 41/46

Youguang was a linguist considered to be the father of modern China’s Pinyin Romanization writing system. Adopted by the People’s Republic in 1958, Pinyin has virtually become the global standard because of its simplicity and consistency. He was 111. Full obituary

(Wang Zhao / AFP/Getty Images) 42/46

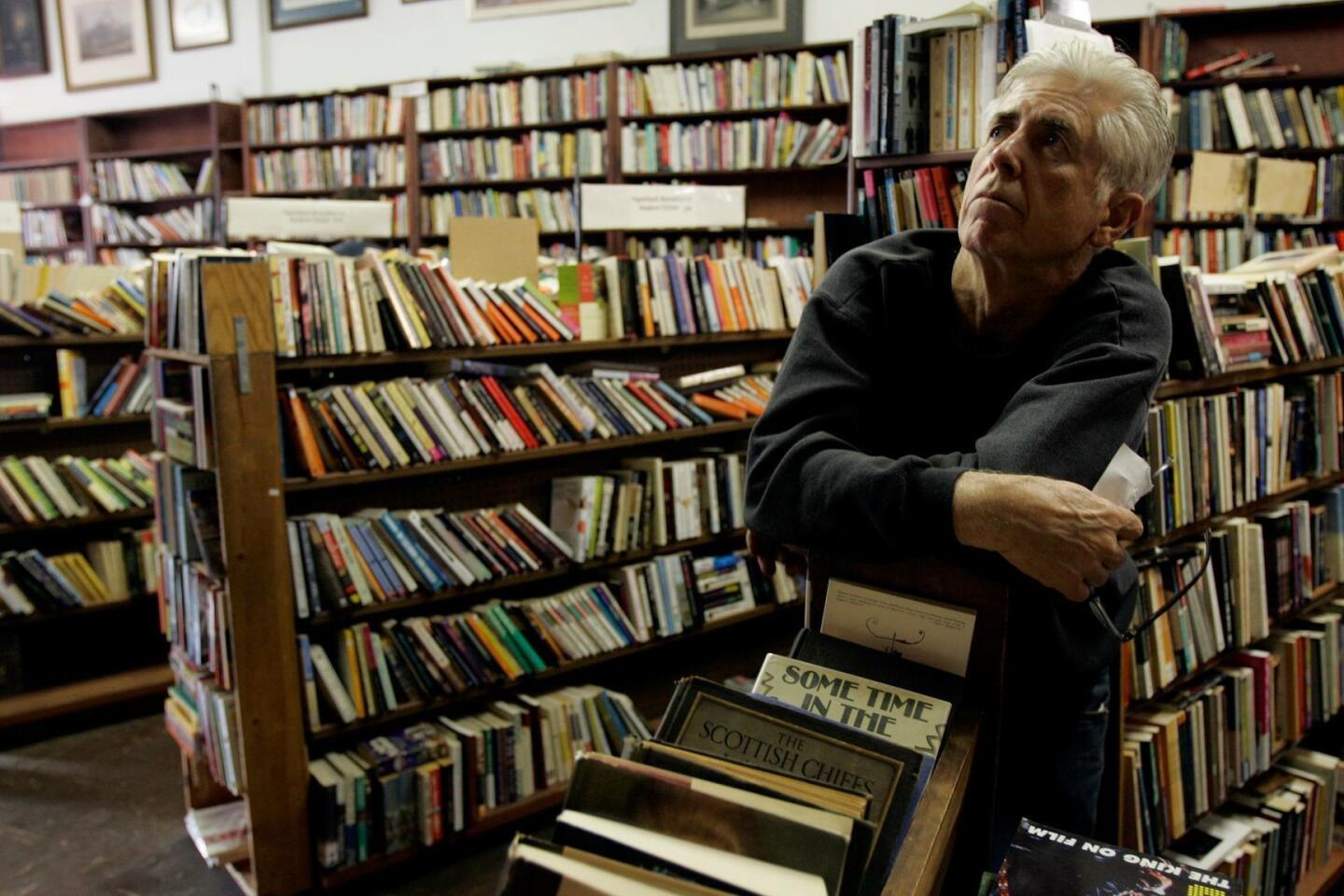

Dutton was the owner of Dutton’s Books, a Los Angeles landmark with its overflowing shelves and hard-to-find titles. Dutton’s Books on Laurel Canyon Boulevard, along with sister locations in Burbank and downtown Los Angeles, was at the very center of literary L.A. when it opened in 1961. He was 79. Full obituary

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) 43/46

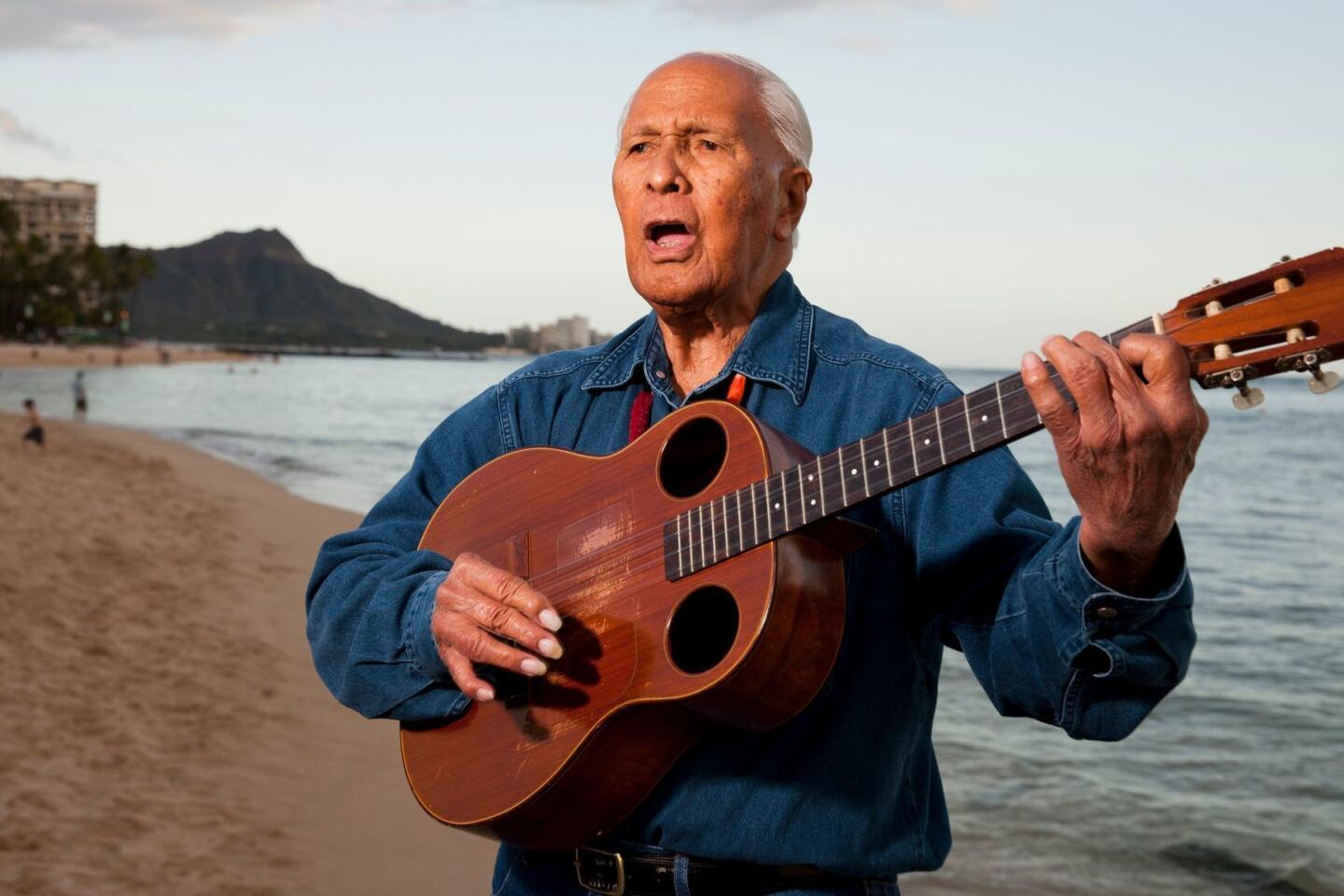

Kamae was one of the most influential Hawaiian musicians of the last half-century and a filmmaker who painstakingly documented the culture and history of the islands. He had long been the face of the Sons of Hawaii, a popular recording group and a pioneering force in traditional island music. He was 89. Full obituary

(Marco Garcia / For The Times) 44/46

The British war correspondent was the first journalist to report the Nazi invasion of Poland that marked the beginning of World War II. She won major British journalism awards, and was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II. She was 105. Full obituary

(Mike Clarke / AFP/ Getty Images) 45/46

The former Iranian president was an aide to Iran’s revolutionary supreme leader, the late Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Although Rafsanjani’s legacy was tarnished by allegations of corruption and authoritarianism, his backing helped moderate President Hassan Rouhani win election in 2013, setting the Islamic Republic on a path to ending its disputed nuclear program and easing its isolation from the West. He was 82. Full obituary

(Ebrahim Noroozi / Associated Press) 46/46

A scholar of world religions, Smith is best known for his work “The Religions of Man,” first published in 1958. It was reissued as “The World’s Religions” in 1991 and has sold about 2 million copies. His informed yet accessible prose led many laymen to read his books as their introduction to religions of the East and West. He was 97. Full obituary

(Tina Fineberg / Associated Press) Two years after Berman launched his stand-up career at Mister Kelly’s in Chicago, his 1959 debut comedy album, “Inside Shelley Berman,” became the first comedy album to earn a gold record and was the first to win a Grammy.

Berman appeared frequently on “The Ed Sullivan Show,” “The Jack Paar Show” and other top TV variety shows, and he is said to be the first stand-up comedian to perform in concert at Carnegie Hall.

At the height of his fame in 1963, Berman was the subject of a TV documentary, “Comedian Backstage,” which unexpectedly sent his career into a tailspin.

The hourlong documentary, which aired on NBC’s “The Du Pont Show of the Week,” offered a close-up look at the chain-smoking comedian on stage and off, including an engagement in a Florida hotel.

On stage, he’s shown doing a semi-autobiographical routine at the end of his act in which a Yiddish-accented father reluctantly gives in to his son’s request for $100 to go to acting school. The routine ends with the father saying, “Sheldon, don’t change your name. Goodbye, Sheldon.”

It was a poignant piece of material that was shattered, ironically, by the sound of a telephone ringing backstage.

Berman completed the piece and ended his show. But, as recounted in a 2005 Times story, the seething comedian “went backstage and yelled at his road manager, [then] he jerked the phone off the hook and paced, appearing inconsolable.

“Seen today, it is not so much remarkable for the behavior it exposes as the pain of the man, on naked display, a perfectly good show ruined, in his mind, by one or two seconds of ringing telephone. Wound tight the entire hour, Berman gives the special its climax — he comes undone.”

After the documentary aired, Berman’s on-camera loss of temper turned him into what Los Angeles Times TV reporter Hal Humphrey described at the time as “the most cussed and discussed comedian in the country.”

Berman told Humphrey that comedians expect drunks and hecklers to interrupt their acts, “but I thought I had taken care of this phone. It had rung earlier in the week, and I ordered it taken care of.”

But for dramatic purposes when the film was edited, the second intruding phone call that had him fuming was placed first.

Although Berman had control over what went into the documentary, he later said he did not think the backstage incident made him look bad. Instead, he told Phil Berger, author of “The Last Laugh,” a 1975 book on stand-up comics, “I thought it made me look like I cared. ... I was more wrong than I ever dreamed.”

Indeed, the infamous moment that was captured on film had a profoundly negative effect on Berman’s career, one with long-lasting repercussions.

“A lot happened and a lot didn’t happen,” Berman said in the 2005 interview. “So that this thing that aired in 1963 would result a few years later in personal bankruptcy, would result in having people be on edge with me, wondering when I’m going to blow up. This would result in my trying to over, over-compensate by [saying], please and thank you, no matter what happened.

“It became, very simply, that I was difficult.”

Not that there wasn’t some truth behind the allegations; Berman had a reputation in the business for being a perfectionist, temperamental and demanding.

Because his act was more theatrical in nature than that of other comedians, he always was concerned about having the proper lighting and eliminating unnecessary distractions — bartenders, for example, were told not to use blenders during his act. And, according to various accounts, he was known to insult, with no trace of humor, hecklers and other audience members who interrupted his act.

Berman’s intensity, according to Nachman’s book, lessened after his 12-year-old son, Joshua, died of a brain tumor in the late `70s.

“I used to think of my performances as life-and-death,” Berman said in a 1977 interview. “They are not life-and-death. This I know. I used to be antagonistic, arrogant and far too worried about my own performance. If an audience didn’t laugh, I was devastated!”

But, he candidly admitted, “I haven’t been cleansed. I still think I’m a son of a bitch. When I’m working I don’t want anyone to screw me up. I don’t want anyone to play around with my lights, my microphone.”

He was born Sheldon Leonard Berman in Chicago on Feb. 3, 1925. After serving in the Navy during World War II, he enrolled as a drama student at the Goodman Theatre in Chicago, where he met aspiring actress Sarah Herman, whom he married in 1947.

He eventually ended up in New York City. While making the rounds of auditions, he wrote sketches for Steve Allen’s “Tonight” show in the mid-`50s, then returned to Chicago to join the Compass Players.

Doing improvisations with fellow performers such as Mike Nichols, Elaine May and Barbara Harris, Berman earned a reputation for what has been described as his compulsion to dominate the scenes in which he appeared.

“I was hungry for recognition,” he told Janet Coleman, author of “The Compass,” a 1990 book about the influential improvisational group.

During his stand-up comedy heyday, Berman appeared in the short-lived 1959 Broadway musical revue “The Girls Against the Boys” and starred in the 1962 Broadway musical comedy “A Family Affair.” He returned to Broadway in 1980 with a one-man show.

Berman always viewed acting as his “first love,” and he had guest roles on numerous TV series over the years, as well as playing the recurring role of eccentric Judge Robert Sanders on “Boston Legal” (“I will not tolerate jibber-jabber in my courtroom!”).

He also acted in movies, including “The Best Man” and “You Don’t Mess with the Zohan,” and he taught a graduate class in humor writing at USC.

Late in his career, he played Nat David, father of Larry David, on HBO’s “Curb Your Enthusiasm.” With dialogue improvised by its cast, the comedy series gave Berman the opportunity to return to his improv roots and introduced him to a new generation of TV viewers. He also appeared in the movie “Meet the Fockers” before retiring in 2014.

Berman is survived by his wife and a daughter, Rachel.

Dennis McLellan is a former Times staff writer.

A Times staff writer contributed to this article.

ALSO

Richard Anderson, costar of ‘The Six MIllion Dollar Man’ and ‘The Bionic Woman,’ dies at 91

Larry Sherman, actor, journalist and Trump’s first publicist, dies at 94

Tobe Hooper, ‘Texas Chain Saw Massacre’ director, dies at 74