Beyond the airwaves, Prop. 46 backers and opponents use grassroots tactics

Reporting from Sacramento — The battle over Proposition 46, the medical malpractice and drug testing initiative, has led to a deluge of TV and radio ads, mostly from the opposition.

But although the fight on the airwaves may be the most visible element of the campaign, both sides are also using grassroots tactics to get their message out.

The California Medical Assn. has supplied physicians with reading material for patients: brochures in English and Spanish, as well as small rectangular handouts dubbed “lab coat cards,” which fit in a doctor’s front pocket. The cards outline the ‘no’ side’s arguments and advertise its campaign’s website, Facebook account and Twitter page.

Dr. Ruth Haskins, an obstetrician and gynecologist in Folsom, said she is against the initiative and tells her patients the measure could affect her ability to practice.

“Common sense tells me that if I currently have to carry up to $250,000 [in malpractice insurance] and if I’m going to have to cover up to $1.1 million, I’m certainly going to have to pay more,” she said.

The initiative would increase the state’s limit on certain malpractice damages from $250,000 to $1.1 million and index it to inflation going forward. It also would require hospitals to test their physicians for drugs and alcohol.

A third provision would mandate that doctors check a statewide prescription database before prescribing certain medications in hopes of reducing “doctor shopping” by drug abusers.

The measure’s backers have their own network of advocates: victims of medical malpractice.

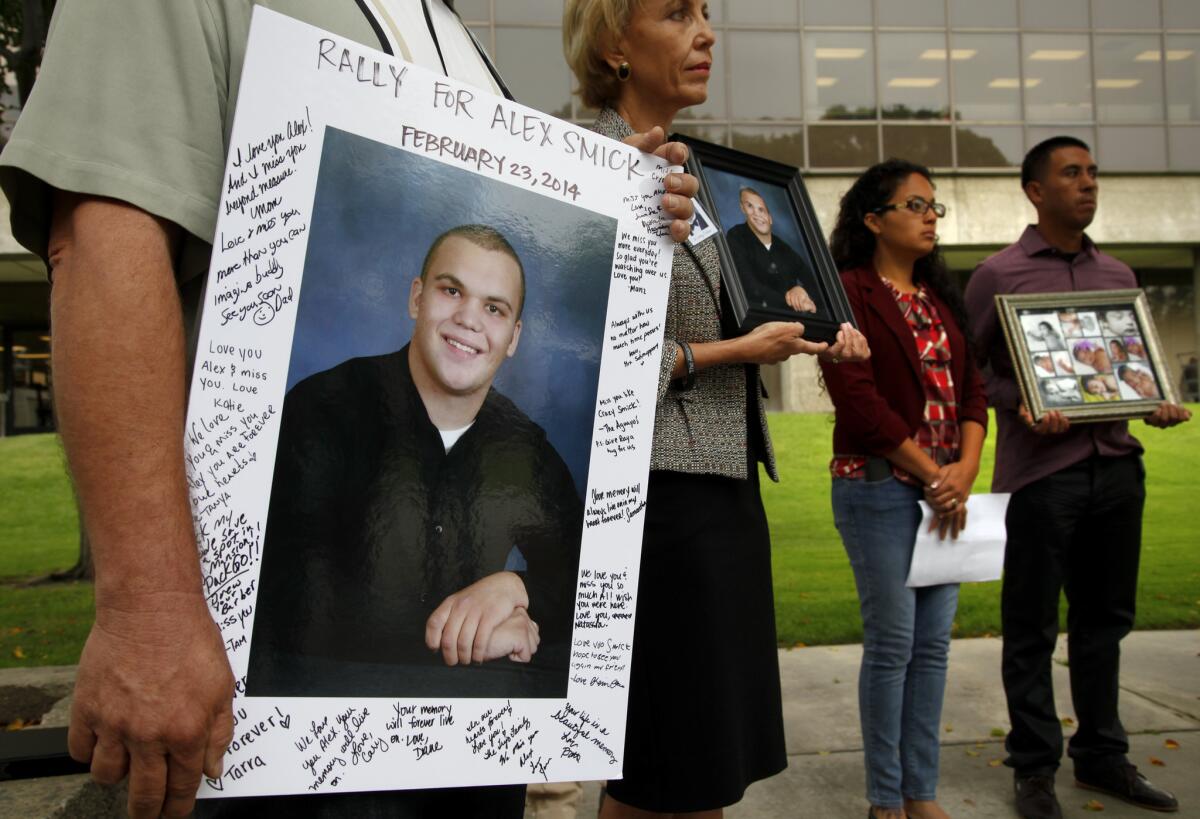

Tammy Smick, a teacher from Downey, has appeared at political clubs, schools and city council meetings to talk about her son Alex, who died two years ago at age 20.

Alex, who had become addicted to prescription drugs after a back injury, checked into Mission Hospital in Laguna Beach to detox. Smick says her son was given excessive medications and left unmonitored for seven hours. He was found dead when a nurse finally checked on him.

Smick said sharing her son’s story “doesn’t get any easier. Every time I stand up in front of an audience and tell his story, I cry.”

But, she added, “it feels like there’s a real purpose in me sharing this story.”

Follow @melmason for more on California government and politics.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.