Man flooded the town of Iola; now nature is bringing back its ghost

Reporting from Gunnison Valley, Colo. — Whenever Bob Robbins would ride the school bus past Blue Mesa Reservoir, he felt a pang in his gut.

The vast shimmering lake, the largest in Colorado, was a recreational paradise for many and a source of power and water storage for the Gunnison Valley and beyond.

But it was once something else.

Robbins grew up here in a speck of town called Iola, where he spent a carefree youth among the shade trees and green meadows before it was all submerged beneath 60 feet of water. The school house, the family ranch, the general store, even the majestic old cottonwoods — all were flooded in the early 1960s to make way for the reservoir.

Then Blue Mesa began drying up in Colorado’s persisting drought, dropping more than 80 feet last year.

And Iola reemerged.

That is, what’s left of it. Anything that couldn’t be sold or moved had been burned so it wouldn’t float to the surface, even the cottonwoods. World War III, was how some residents described the incessant blasting of rock walls, the flying debris and the burning that ushered in the inundation.

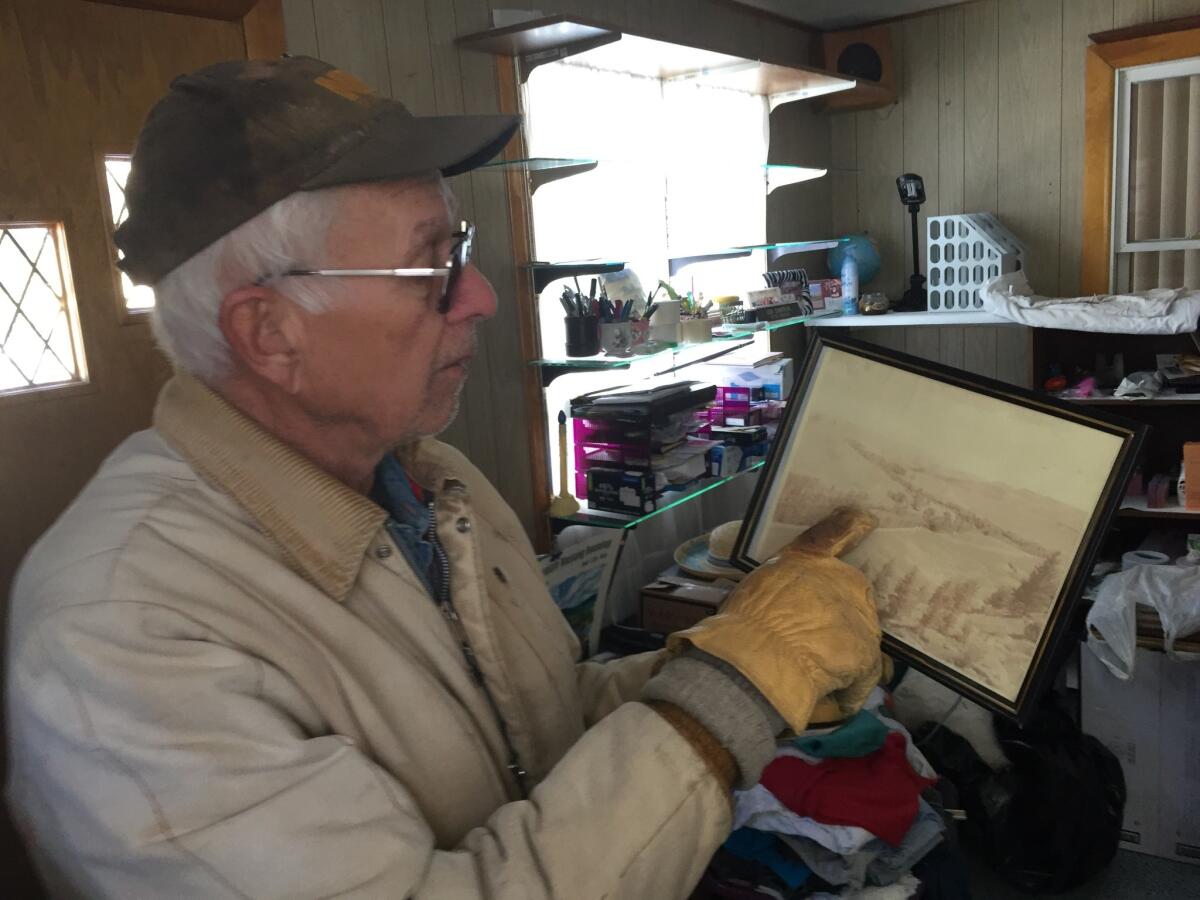

At first, Robbins, 69, resisted the urge to visit what had been Iola, his family’s home for five generations. The memories were too raw. But curiosity got the better of him.

On a recent day, he parked his Jeep and walked down a hill to the snowy, desiccated lake bed with David Primus, who has studied the history of the Gunnison Valley for over 40 years.

The once verdant little town of about 30 people was mired in muck, rusted artifacts strewn about. They located the foundation of the old Iola School. Robbins picked up a piece of a school desk.

“I was the only kid in my class here,” he said.

He found the base of the flag pole with his father’s and grandfather’s initials carved in it. A few yards away lay the ragged outlines of the Big Little Store, the Iola Hotel and the old Standard service station. Pipes poked from the ground. A roller from a washing machine lay in the snow beside scattered railroad spikes. Atlantis in miniature.

Robbins’ family homesteaded the valley in 1877. They ranched, raised horses and grew hay. A rich stretch of the Gunnison River, later swallowed by the reservoir, flowed through here.

The willow fly hatch every July was broadcast on Denver radio stations. The flies were catnip to the rainbow trout, which in turn lured the fishermen, including anglers such as John Wayne and President Herbert Hoover.

But as the West grew, so did the demand for water and hydroelectric power. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation decided to dam the Gunnison and flood about 20 miles of the valley. The National Park Service would turn the enormous reservoir into a recreational area.

“We started damming up everything in the name of flood control, power, recreation, but we destroyed a lot of beautiful countryside, businesses and people’s livelihood,” Primus said. “And what did they lose? I think the human side of this is very compelling.”

Robbins was a teenager when his father broke the news.

“Dad said we were in trouble,” he recalled.

The federal government promised to pay a “fair market rate” for their property. They could take whatever they wanted. Anything left behind would be burned.

Dam construction began in 1962, and the reservoir reached full capacity eight years later.

“Dad was furious. He died furious. He never forgave them,” said Robbins, who left Iola in 1964 when he was 15. “I will probably never forgive them.”

His father put a down payment on the Crescent Motel in Gunnison.

“And that’s where we lived,” Robbins said.

Their home in Iola was torched.

A string of fishing resorts including Trout Haven Resort, Rippling River Resort and the Elkhorn Resort were also flooded. The Neversink Resort sank. The little towns of Cebolla and Sapinero were swept away.

The exact number of residents affected is unknown, but Primus figures it could be around 300.

In the years after, Robbins would ride past the reservoir on the school bus going to football games in Montrose or other mountain towns. He saw boats motoring over what had been his hometown, water skiers zipping over the waves. And his heart sank.

“I genuinely loved this place,” said Robbins, a retired pilot. “I don’t remember wanting to be anywhere else.”

He recalled a halcyon youth of waking at dawn and returning home at dusk. He’d spend the days wandering the meadows, riding horses with his uncle and fishing the clear Gunnison. He baled hay and fed the animals.

“This used to be jackrabbit heaven. There used to be sage grouse everywhere. You would find 50 sage grouse when you walked out the door. Now they are nearly extinct,” he said. “Game would cross here — elk, deer. They are pretty much gone. This is just dead space now.”

Iola lies at the shallow end of the reservoir. Bits and pieces have surfaced in the past. During one dry spell, Robbins drove his mom out to look at the old ranch foundations.

“She broke down and bawled so much that I had to take her home,” he said.

Robbins lives on his own ranch now, not far from where he grew up. He struggles with his family’s loss to this day and wonders if it was all worth it.

“Lake Mead and Lake Powell are way down and may never fill up. Then Phoenix and Las Vegas are in trouble,” he said. “We have enabled the desert west of us, and now they need water. But everywhere you look there is drought. How do you climb out of this hole?”

High demand and the sustained drought throughout the Southwest have caused Blue Mesa to shrink, and there’s little relief on the horizon.

“Last winter we had very little snow, and it never really filled up,” said Sandra Snell-Dobert, public information officer at the Curecanti National Recreation Area where the reservoir is located. “The dry winters and dry summers are taking a toll. Right now, it’s about 37% full. It could be at the lowest point since it was filling up.”

Primus, community engagement facilitator at Western Colorado University in Gunnison, said the vanishing reservoir had ignited interest in the history beneath it. He does slideshows and lectures throughout the area on the history of the region.

“They are hugely popular,” he said. “It’s not me, it’s the fact that what was there isn’t there anymore, and that’s what makes it so compelling.”

Bill Sunderlin, 78, a gunsmith, lives just up the road from the reservoir. His grandparents owned the Tex Lodge Ranch Resort, which submerged when the reservoir was being filled.

“We fought that reservoir for years,” he said. “They came calling one day and said they would give us this amount and if we didn’t like it we could go to court. We owned a mile of the Gunnison River and they gave us $160,000. Imagine what that would be worth today?”

He still retains part of the town.

Before the flooding started, over 100 buildings were saved. That included several cabins from the family resort that now stand on a hill behind his home. And the old Iola School became his house. He walked through his living room, noting where the teacher would pull across a curtain to put on school plays.

“I went through eight grades of school there and now I get to live in it,” he said. “Is that poetic justice or what?”

Kelly is a special correspondent

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.