As U.S. releases thousands of asylum seekers at the border, volunteers struggle to keep pace

Reporting from McAllen, Texas — Federal immigration officials dropped the first group of several dozen asylum seekers — all Central American parents with children — at the downtown bus station here just before it opened at 5 a.m. Thursday.

They dropped more throughout the day, all of them Spanish speakers in need of food, medicine and guidance from local volunteers.

Jose Manuel Velasquez, 24, cradled his squirming 3-year-old-daughter, Sofia, as volunteer Susan Law advised him how to reach Oklahoma City, where he hoped to join his cousin. He was one of thousands of asylum seekers trying to leave the border region this week to reach friends, family and immigration court hearings in other parts of the country.

Across the border this week ahead of President Trump’s Friday visit to California, volunteers helped hundreds of asylum seekers who had been released from U.S. custody. Cities are pitching in, but helping the migrants has mainly fallen to volunteers whose resources were already at a breaking point from responding to a slew of new immigration policies.

On Thursday in McAllen, the U.S. released 700 migrants to crowded nonprofit shelters and dropped others directly at the bus station. Some arrived at the station with confirmation numbers to claim tickets paid for by relatives. Many arrived confused.

Law, one of half a dozen regular volunteers with the group Angry Tias and Abuelas of the Rio Grande Valley, said the constant arrivals this week made volunteers’ work “more overwhelming.”

The 73-year-old, a retired human resources director for Texas RioGrande Legal Aid, sat with one parent after another Thursday. She explained each step of their bus trip, highlighting connections on a stack of U.S. maps she keeps tucked in a clipboard.

She reviewed their paperwork, reminded them to keep their addresses updated and attend immigration court, and shared a list of free legal services at their destinations.

Many eastbound buses arriving in McAllen on Thursday were already packed with those released in El Paso and San Antonio. The wait time for migrants released to shelters to make it onto a bus has stretched to two days, according to Eli Fernandez, a volunteer at a nonprofit shelter.

Migrant advocates have suggested that recent mass releases at the border were intended to create chaos and give Trump something to point to when he argues that there is a national emergency.

Border Patrol officials have said their resources were strained by people crossing into the U.S. and asking for asylum. The officials have asked for millions more in funding to run temporary holding areas in Texas’ Rio Grande Valley.

A Federal Emergency Management Agency team arrived in the valley this week, meant to support Border Patrol operations and nongovernmental groups, according to a FEMA spokeswoman. But many volunteers in the Rio Grande Valley said they hadn’t been contacted by the agency.

Should activists aid migrants in the desert, or leave their fate to the Border Patrol? »

Trump policies blocking asylum seekers led volunteers to found Angry Tias and Abuelas about a year ago, after U.S. officials blocked asylum seekers at a border bridge south of McAllen. They brought food and supplies to the bridge and kept helping migrant families once Border Patrol started separating them. As immigrant parents were released, the volunteers shifted to the bus station to assist Catholic Charities, which runs a nearby shelter.

Most of the volunteers in Angry Tias and Abuelas are local, some are winter Texans, and others out-of-state visitors.

Luis Guerrero, a retired firefighter, remembers a 4-year-old Salvadoran girl explaining, as her parents looked on, why they had to flee to the U.S.: Armed men, one in a ski mask, had broken into their house and demanded money. The house was clay, with a dirt floor, she said.

“If you stay here,” Guerrero told the couple, “make sure your daughter gets therapy.”

Many of the migrants are from poor, rural areas and need the most basic help, volunteers said.

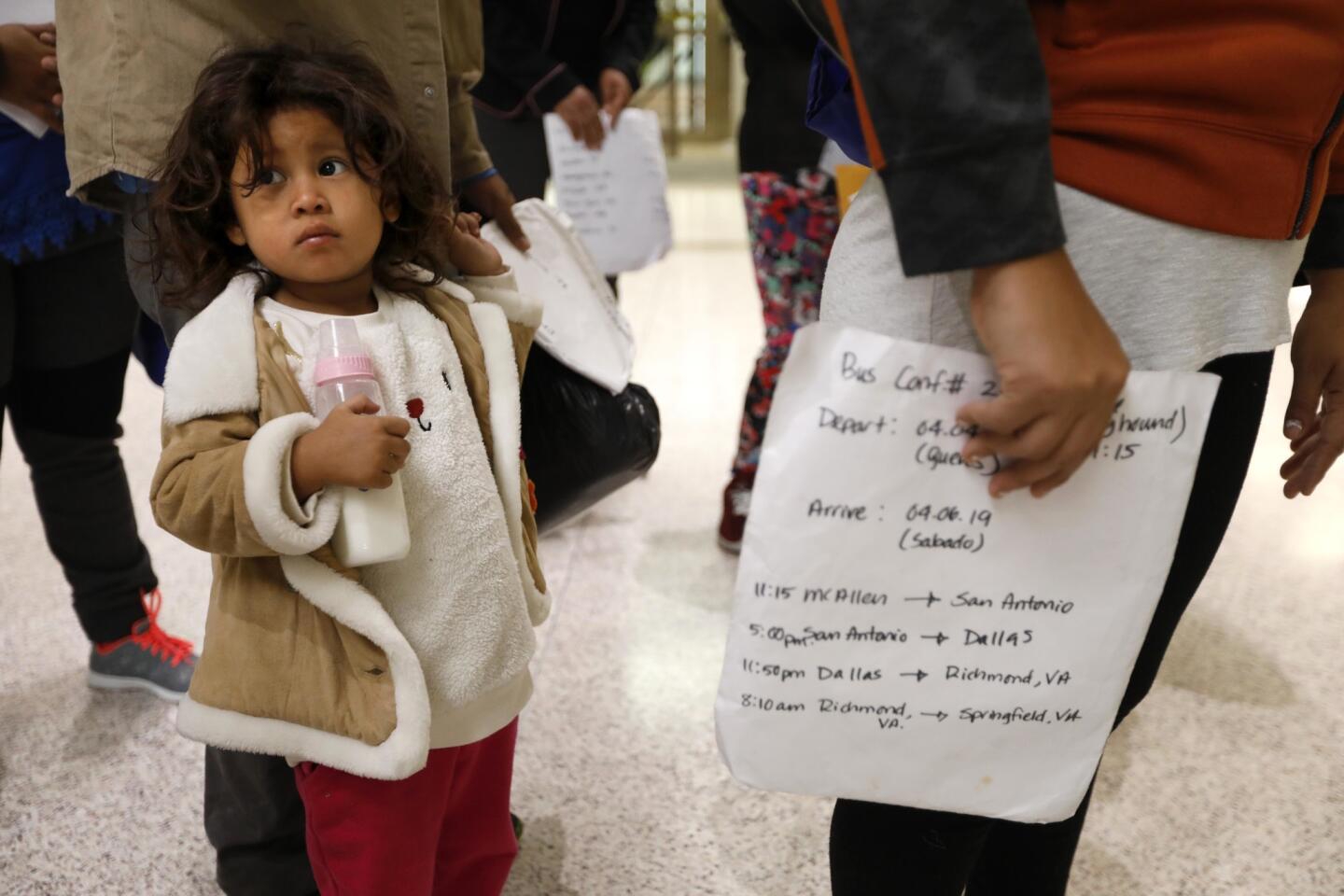

A young Honduran mother paid close attention Thursday as Law traced the route she would follow to join her sister, a legal resident who had migrated years ago and settled in Memphis, Tenn. Olga Lara had brought her 3-year-old, Alva, but left her 13-year-old daughter, Lilia, behind in Honduras with her mother.

Lara, 29, said she hoped to learn to read, as her sister had, in the U.S. She doesn’t know how to spell her name. She has never attended school, she said, because her family couldn’t afford it.

Law ensured the woman was traveling with another migrant who could read, write and look out for her. Law also warned Lara and other female migrants about the risk of trafficking, advising them to stay in main bus terminals and avoid anyone who might try to persuade them to leave.

Lara tucked her ticket into her bra and her paperwork into a bag next to Alva’s Elmo doll. She was wearing a donated puffy jacket and sneakers stripped of shoelaces in Border Patrol detention. Law ran to grab her some of the laces she keeps stashed at the bus station. Lara threaded them through her shoes and thanked the volunteer.

Last week, a family of five arrived at the station shoeless. Law bought them new pairs at a store she took them to up the street before their bus left.

On Thursday, good Samaritans from local churches dropped by with books, toys and hot breakfast tacos for the migrants. But there were not enough tacos to go around. A van from the nearby shelter was delayed when it ran out of gas. A few families boarded buses without eating.

Volunteer Roland Garcia, a former U.S. Marine, loaned his cellphone to a single Salvadoran mother of three, a domestic violence victim, so she could contact family in Houston and book her bus ticket.

“If we could just get more volunteers to help these people,” he said. “To them, everything is new. Some of them don’t even know how to work the Coke machine.”

U.S. border authorities hold migrant families in a pen under an El Paso bridge »

Garcia, 60, who used to be a truck driver, started volunteering after he ducked into the bus station a few months ago to wait during a delivery and saw the crowds. He had been diagnosed with stage 4 pancreatic cancer and felt the need to do something meaningful. He’s already recruited other volunteers.

His friend Rafael Mendoza said volunteers counter misinformation some asylum-seeking families receive from staff in Border Patrol facilities: “You’re wasting your time, you’re going to lose your case, you’re not welcome here.”

“Our own agents are telling them that,” said Mendoza, 59. “It’s very discouraging.”

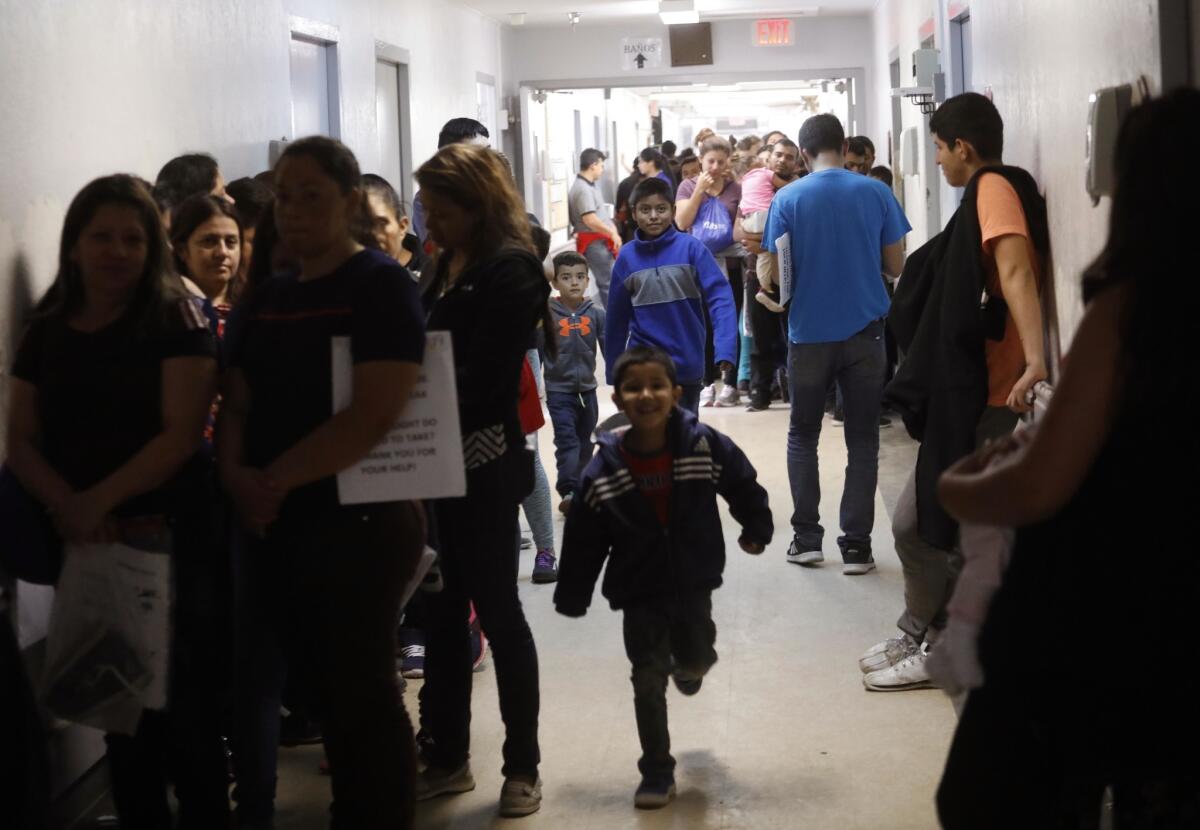

The Catholic Charities shelter was packed Thursday, even after opening a second site when the Border Patrol started releasing large groups of families two weeks ago. The shelter’s halls were full of parents with small children who had not bathed in days, held in chilly Border Patrol cells where they said they caught colds and fevers.

Honduran Eulogio Erazo Varela said his 3-year-old daughter developed a fever while they were held for almost a week, first in a Border Patrol holding cell — what migrants call a hielera, or icebox — then behind a chain-link fence in a converted warehouse.

He was relieved to meet volunteers at the bus station Thursday, who he said treated him kindly as he prepared to catch a bus to Memphis — unlike Border Patrol agents, he said, who didn’t provide much treatment or help.

Many of the volunteers, including Law, had caught the migrants’ colds. But they were determined to keep helping. Law has driven a few migrants whose families could afford tickets to the airport, and hoped to recruit more volunteer escorts to help them navigate air travel in coming weeks.

Law recalled a migrant mother she met Wednesday, confused by her bus itinerary until the volunteer walked her through it in Spanish. Afterward, the woman said she would have been lost without Law’s help.

“That’s what keeps me going,” Law said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.