After Oklahoma City bombing, McVeigh’s arrest almost went unnoticed

Reporting from Perry, Okla. — Like all the local legends in this little town, Charlie Hanger has a portrait hanging on the wall of the Kumback Cafe, between the photo of outlaw Pretty Boy Floyd (said to have once eaten the biggest steak in the place) and the state champion wrestling teams.

“Town Hero,” Hanger’s photo says.

On April 19, 1995, Hanger — an Oklahoma Highway Patrol trooper so by-the-book that locals swore he’d ticket his own mother — arrested Timothy J. McVeigh, 90 minutes after a fertilizer bomb in a Ryder rental truck exploded outside the federal building in Oklahoma City.

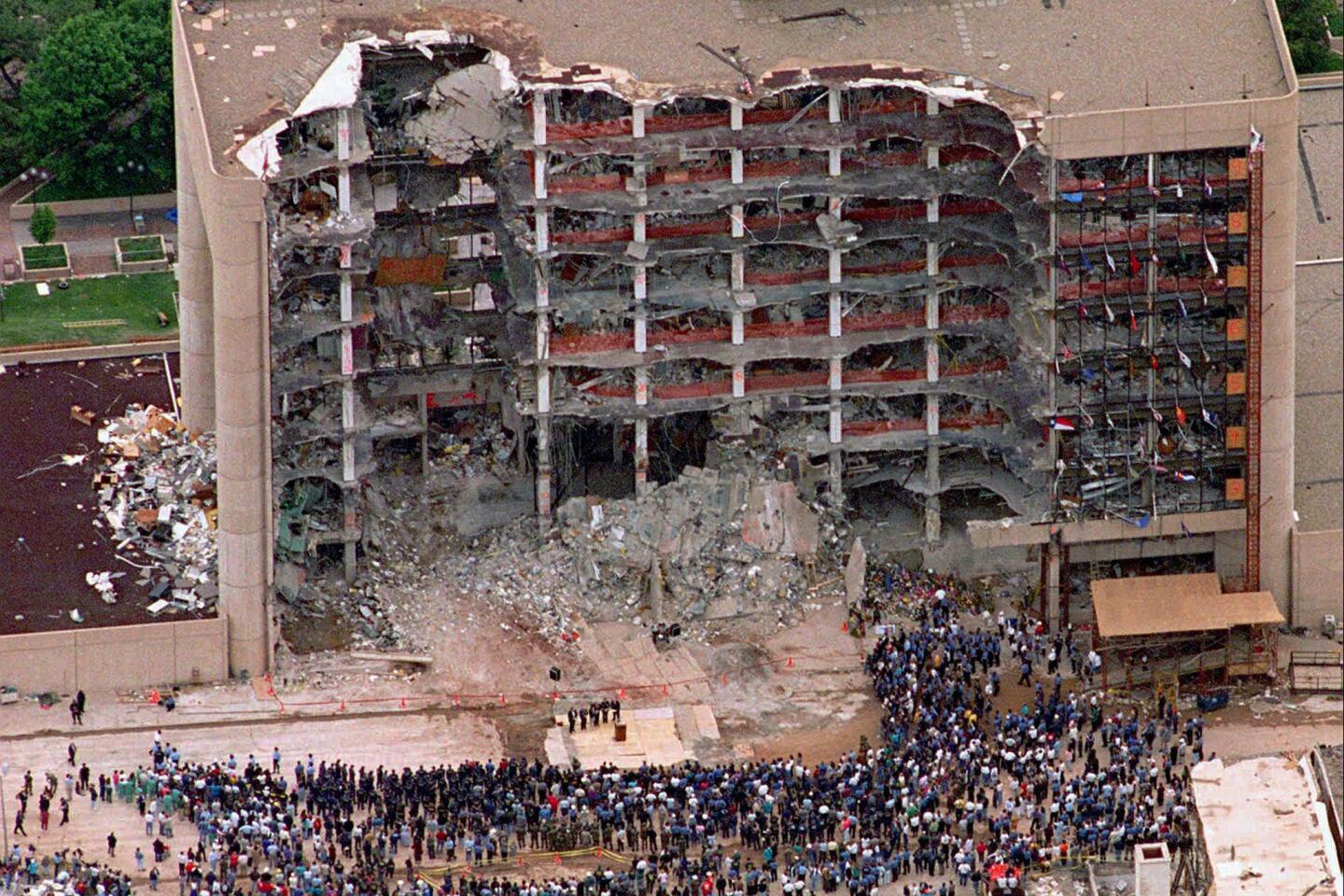

Sunday marks 20 years since the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building, which killed 168 people and injured hundreds more in what was then the deadliest terrorist attack on U.S. soil.

Around these parts, Hanger —a quiet, unassuming man who now serves as sheriff of rural Noble County —will forever be known as the Man Who Caught McVeigh. To hear Hanger tell his story is to recall how skilled police work, but also luck, led to the arrest of the decorated Army-veteran-turned-radical who was later convicted and executed.

“I call the fact that I was put in the right spot at the right time divine intervention,” Hanger said last week. “I’ve never sought attention for it. I’m not a person who likes a lot of attention.”

On that cool spring morning, Hanger had been ordered to the disaster site and had driven just few miles outside Perry — a town of about 5,000 people 60 miles north of Oklahoma City — when he was told to stay in his area.

Hanger was driving north on Interstate 35 when he passed a rusting, yellow 1977 Mercury Marquis with no license plate. He stopped the car and found behind the wheel a clean-cut, 26-year-old Timothy McVeigh wearing military boots and a windbreaker.

McVeigh also wore a T-shirt with a picture of Abraham Lincoln and the words his assassin, John Wilkes Booth, shouted in Ford’s Theater: “Sic semper tyrannis.” (“Thus always to tyrants.”) On the back was a quote from Thomas Jefferson: “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.”

McVeigh didn’t have proof of insurance or a bill of sale for the car. He told the always-suspicious Hanger that he was on a long, multi-state drive — moving to Arkansas and on his way to get more of his belongings. But there was no suitcase in the car. No change of clothes, either.

As McVeigh reached into his rear pocket for his driver’s license, his windbreaker tightened, and Hanger noticed the bulge of a shoulder holster under his left arm. McVeigh was wearing a loaded Glock pistol and had a 6-inch knife on his belt.

“My gun is loaded,” Hanger recalled McVeigh telling him as Hanger grabbed the bulge under the jacket.

“So is mine,” the trooper responded, putting his own gun to McVeigh’s head before arresting him for unlawfully carrying a concealed weapon. If he hadn’t spotted the bulge, he would have let McVeigh go with a ticket.

As Hanger drove back to the Noble County Courthouse, McVeigh, sitting in the passenger seat, rattled off the serial number of his gun, correctly except for a single digit. He asked Hanger how fast his car ran, what kind of firearm he carried, how he could get his own gun back.

“I thought it was just nervous chatter,” Hanger said. “The radio was going. They were still sending units to Oklahoma City. I never made any comment about it and he never made any comment about it. I thought, ‘He’s just passing through. He doesn’t know what’s going on.’”

Hanger booked McVeigh into the Noble County Jail, inmate 95-057, and took his wife to lunch. Like everyone else, he was glued to the TV news coverage of the bombing.

As the nation searched for the bomber and public speculation lingered on men of Middle Eastern descent,McVeigh sat in a concrete cell atop the aging courthouse.

McVeigh was supposed to go before a county judge the next day, Thursday, but his hearing was delayed because the judge got tied up in a messy divorce case. The hearing was rescheduled for Friday.

Hanger was at home that morning when a dispatcher with Highway Patrol headquarters called asking if McVeigh was still in jail. Hanger doubted it, since he could easily make bail, but to his surprise McVeigh was still there, his car still parked by the interstate about 35 miles south of the Kansas state line.

McVeigh’s hearing had been delayed again, this time because the judge’s son had missed the school bus and the judge had to give the boy a ride. McVeigh probably would be seeing the judge any minute, Hanger told the dispatcher. Put a hold on him for the FBI, he was told. Now.

The trail that led to McVeigh had begun with the discovery of the Ryder truck’s rear axle.

Flung two blocks from the blast site, the axle still held the vehicle identification number, which led authorities to the rental agency and then to a motel where McVeigh had stayed, registered under his real name. Staff said he resembled a composite sketch of “John Doe No. 1,” seen near the Murrah Building before the explosion.

Authorities had learned McVeigh was in jail because Hanger had run his Social Security number through a national crime database after his arrest.

Word spread fast in Perry that something was up.

Hanger was back at the courthouse when an angry crowd gathered on the lawn — some screaming, “Baby killer!” Hanger slipped out of the building in plain clothes and rode home with another trooper to avoid attention.

His role quickly got out and people wanted him — reporters for interviews, Oklahomans just to say thanks. Someone went to the local florist and tried to order flowers for Hanger, planning to follow the delivery driver to his home. Someone else sold maps to Hanger’s house to reporters.

Hanger didn’t do interviews, but that didn’t stop locals from talking about the strait-laced trooper. No one seemed surprised it was Hanger who made the arrest. The assistant district attorney told a reporter that Hanger once testified at a trial, and when the 12 jurors were asked if they’d ever received a ticket, 10 of them had been written up by Hanger.

“He was always fair in the enforcement of the law, a no-nonsense type of guy,” said Don Stoops, Hanger’s former partner, now retired.

These days, Hanger says he was just doing his job, though he later realized that, had he made one false move, McVeigh could have shot him on that highway.

“Looking back later at who I was dealing with, what could have happened — that was more frightening than what happened that day,” Hanger said. “I often run the whole scenario back through my mind to see if there was something I missed, something I should have picked up on, and I’m just glad I didn’t let him go.”

The arrest defined Hanger’s career. He was elected Noble County sheriff in 2004 and barely mentioned McVeigh when campaigning. Around here, he doesn’t have to.

Two decades on, McVeigh’s co-conspirator, Terry Nichols, sits in prison while the pain and anger remain potent for Hanger and many Oklahomans. Hanger well remembers McVeigh’s eyes. There was no emotion.

Hanger can recite all the minutiae of the arrest —but when he talked about the 19 children killed that day, the lawman in the black cowboy boots choked up, and his big, blue eyes turned serious. He can’t bring himself to visit a memorial where victims’ photos are displayed.

“The attention needs to be on the victims,” he said quietly. He goes sometimes to the bombing anniversary events in Oklahoma City, but not always. When he’s there in uniform, he feels like a distraction

“He’s so humble about it,” said Marilee Macias, owner of the Kumback Cafe.

“He doesn’t like it when people call him a hero,” she said. But that won’t stop them.

Twitter: @haileybranson

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.