A building boom and climate change create an even hotter, drier Phoenix

Phoenix has morphed into one of the largest U.S. cities.

Reporting from PHOENIX — This sprawling metropolis morphed in a matter of decades from a scorching desert outpost into one of the largest cities in the nation. Today, Phoenix is a horizon of asphalt, air conditioning and historic indifference to the pitfalls of putting 1.5 million people in a place that gets just 8 inches of rain a year and where the temperature routinely exceeds 100 degrees.

Now, however, the city faces a reckoning. It is called climate change, and it is expected to further expose the glaring gap between how the city lives and what it can sustain. The future, scientists say, will be even hotter and drier, the monsoons more mercurial. Summertime highs could reach 130 degrees before the end of the century — think Death Valley, but with subdivisions.

“My colleagues and I wonder about the future habitability of Phoenix all the time,” said David Hondula, a climatologist who studies the impact of heat on health at Arizona State University.

As President Trump rolls back the country’s commitments on climate change, Phoenix is one of many cities facing daunting predictions of what lies ahead, and most have few resources with which to prepare. Public health and economic prosperity are both at risk.

“As we go forward in time and the impacts of climate change become more significant, cities’ resilience will become a factor of competitive advantage,” said Cynthia McHale, who works for Ceres, a nonprofit that promotes sustainability among businesses and investors.

Phoenix has taken steps to react to climate change — expanding public transit and bike lanes, replacing municipal fleets with electric vehicles, putting low-energy bulbs in streetlights and setting goals for reducing carbon emissions.

Yet some cities are now exploring ambitious efforts to adapt to what seems to be the inevitable reality of a warmer future.

Many, including Los Angeles, have created climate resilience programs. Mayor Eric Garcetti has pledged to reduce the average temperature in the city by 3 degrees over the next two decades. To meet the goal, scientists are exploring the benefits of planting trees, installing “cool pavement” and “cool roofs.”

Some coastal areas are mulling over major investments — including New York, where multibillion-dollar sea barriers are being planned, and San Francisco, which projects that 6% of the city will be inundated by the end of the century. Miami Beach is already spending hundreds of millions of dollars to raise streets and install pumps to prevent and relieve flooding.

Phoenix, far from rising seas, faces a different challenge.

The average high here in August now exceeds 104 degrees, but 110 is not uncommon, and the temperature has hit 120 more than once. In summer 2016, a study by Climate Central and the Weather Channel found that the average temperature in Phoenix had increased 1.12 degrees over the previous half a century. No major city saw temperatures rise more — and, of course, no major city regularly reached such scorching highs in the first place.

Phoenix makes its problem worse in several ways: Development has created a local “urban heat island effect,” which limits natural nighttime cooling; only about 11% of the city is covered by trees, which provide essential shade; and the city’s famous sprawl creates emissions that contribute to the overall heating of the atmosphere.

Water presents another challenge. On one hand, Phoenix can tell a remarkable story of steadily improving conservation: Even as the population has soared over the last half-century, the region now uses slightly less water than it did in the 1960s. It also has a formidable supply saved in an elaborate underground storage system created in the 1980s. When California went shrill with drought anxiety last year, Phoenix mostly shrugged.

But the sources that feed the supply and the storage – primarily the Colorado and Salt rivers—are at risk of long droughts in the decades to come, according to climate forecasts.

“We don’t have as much water to put underground as we used to, and we see the handwriting on the wall that that’s going to continue,” said Tom Buschatzke, director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources.

The political climate is brutal as well. Many state leaders do not accept climate science. The Republican-controlled Legislature is so resistant that it fights local action. Last year, it passed a law to prevent cities from requiring businesses to report how much energy they use, though such systems are mandatory in some cities in other states.

Mayor Greg Stanton, a Democrat, says the city has to make its own way, and that means balancing concern with confidence.

“If I don’t sound the appropriate level of alarm that climate change is going to impact our community and that we have to take steps to fight it, I won’t be able to get the reaction that I need to get the policies that we need to pass,” he said. “At the same time, you don’t want to go too far so that you scare off investment, that you scare off business.”

In the last decade, the city that once boasted that it did not need a traditional downtown has nurtured downtown development. In 2015, voters approved a $32-billion transportation plan that included a substantial expansion of a light-rail system. That has help spur a rush of apartment and condominium construction nearby, lured new tech companies and increased gentrification of an arts district called Roosevelt Row.

The city’s bike-sharing program has 12,000 registered riders and is looking to add as many as 1,000 bikes. Part of the program’s appeal, said Mark Hartman, the city’s chief sustainability officer, is that “Phoenix is 100% flat.”

Last month, amid reports that Trump may attempt to withdraw the United States from the historic Paris climate accord, the city moved in the opposite direction: It adopted a goal to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 40% by 2030 from 2005 levels — after exceeding its previous goal of 15%.

Yet increasing density and reducing carbon emissions are not necessarily the same as adapting to climate change. Although Phoenix has a plan to expand its tree canopy, there is little money for other ideas, and it faces stiff competition for grants. The city was rejected last year by the Rockefeller Foundation when it sought money to hire a climate resilience officer.

Phoenix’s new climate program, Resilient PHX, is staffed with two “resilience engagement coordinators,” but they were assigned to the city for temporary terms through the AmeriCorps service program, which Trump has proposed cutting. The budget for two years, also provided by grants, is $40,000.

Without money for major projects, the program’s goal is to help residents help themselves, particularly those in lower-income areas. Last summer, the program enlisted a Boy Scout who needed an Eagle Scout project to organize volunteers to hand out maps to inform people where they could find free water and shade on excessively hot days. The program has also worked to expand shade in low-income areas with heavy pedestrian traffic. Last year, it planted 33 trees.

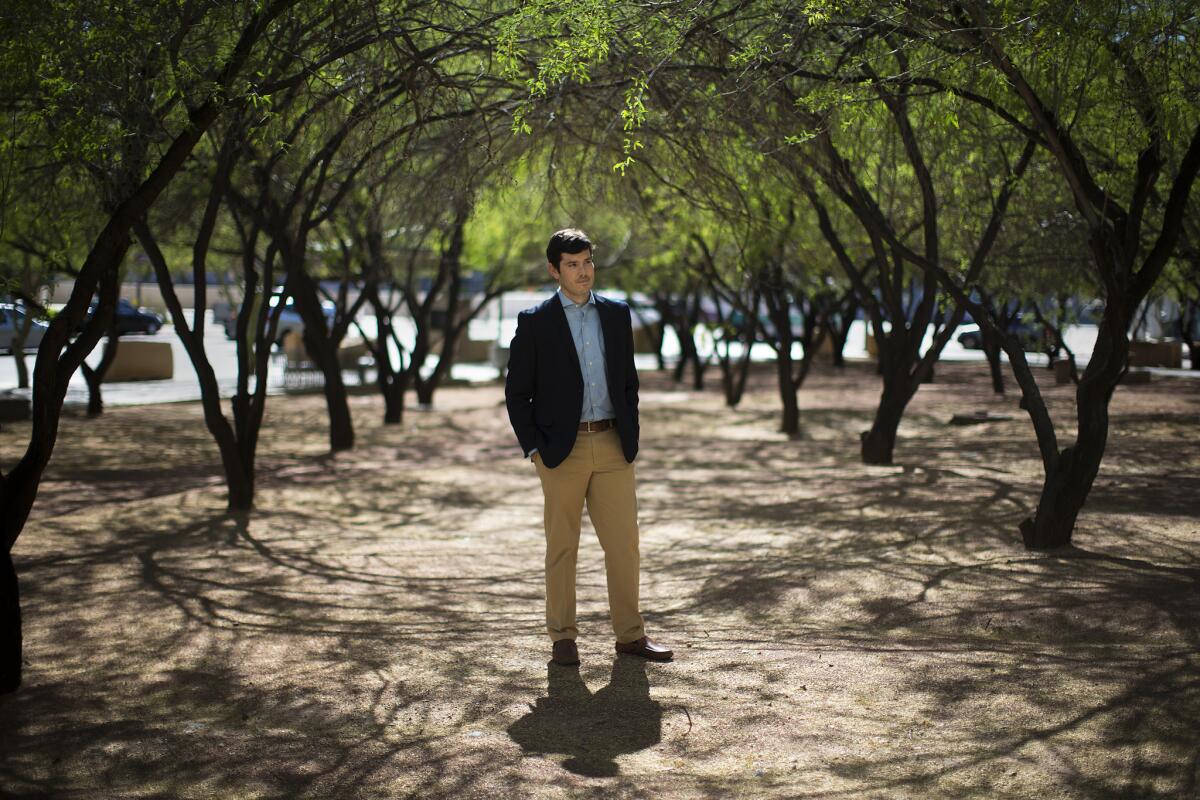

Nick Roosevelt, one of the resilience coordinators, is acutely aware of the small scale of his work relative to the challenge. His great-great-grandfather President Franklin D. Roosevelt created an earlier public service organization with far more resources, the Civilian Conservation Corps. Its workers helped expand the ambitious canal system that now quenches Phoenix’s thirst. Further back in his lineage, President Theodore Roosevelt built the giant dam that made Phoenix possible in the first place.

Roosevelt also knows that his ancestors’ efforts to settle the Southwest helped create some of the challenges he is now trying to address.

“Arguments can be made that people should not live in the desert or along the coasts,” Roosevelt said. “But people are there and what are we going to do about it?”

Twitter: @yardleyLAT

ALSO

Trump blames GOP conservative faction for blocking healthcare bill

How do you memorialize TWA, a dead airline? Attendant uniforms, planes and a voodoo doll

What you need to know about Utah’s .05% drinking limit in 7 numbers

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.