Heat and drought devastate sockeye salmon fishing and spawning on Washington rivers

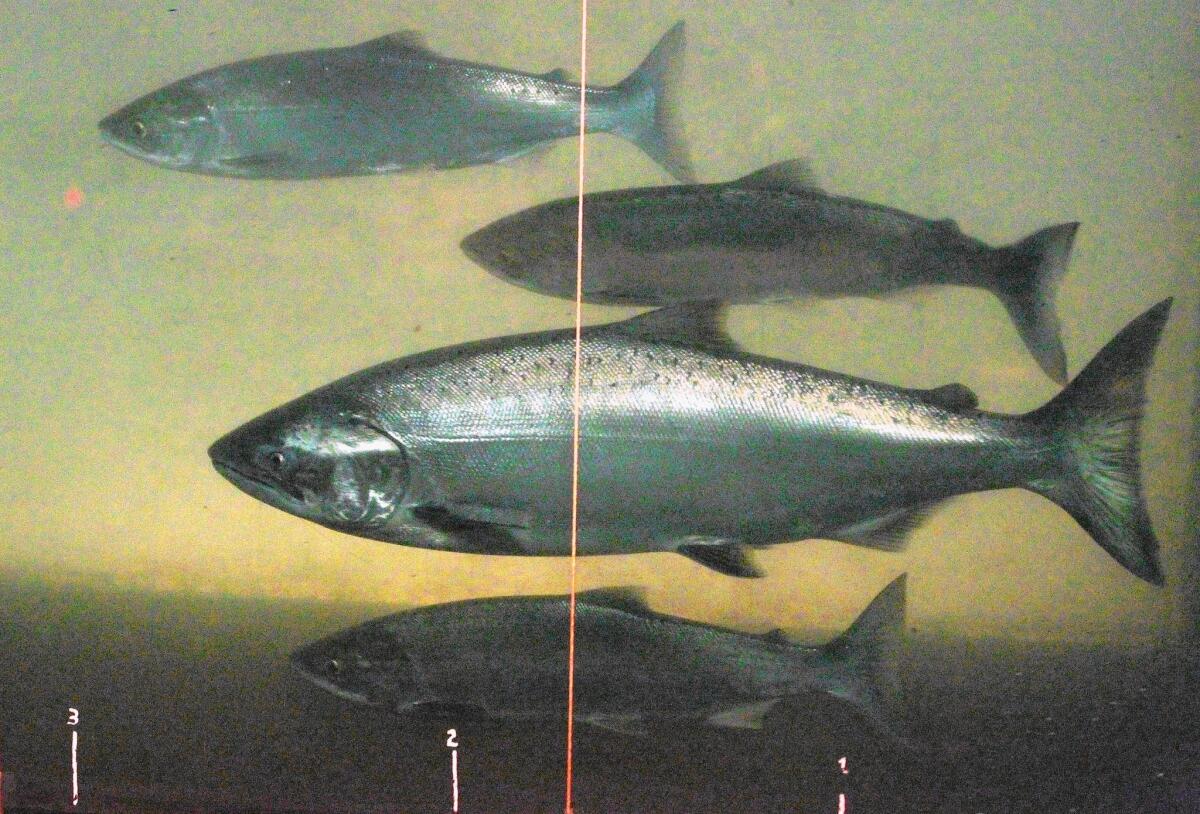

A chinook salmon, second from the bottom, swims with sockeye salmon at the Bonneville Dam fish-counting window on the Columbia River in Washington in 2012.

Reporting from BREWSTER, Wash. — Here at the confluence of the Okanogan and Columbia rivers, tens of thousands of sockeye and chinook salmon stage themselves every summer in an underwater base camp, waiting to make a final push to higher elevations in Canada and their cold-stream destiny: spawning.

Their layover here in the “Brewster Pool,” home of the annual Brewster King Salmon Derby, is usually brief but it can make for fishing bliss.

This year, though, the only salmon that can legally be caught in the derby that began Friday are big chinooks. The much smaller sockeye salmon — to many mouths much tastier — have suddenly become off-limits, as fishery managers report a sudden and alarming plunge in their numbers.

Unusually low mountain snowpack and record high temperatures have put much of Washington in a state of severe drought and have also heated water in the Columbia and many of its tributaries to well above 70 degrees — several degrees higher than many sockeye can survive. The heat is believed to have devastated a fish run that just a few months ago was projected to be among the most robust in decades.

Fall fish counts will paint a fuller picture, but federal fishery experts say more than 80% of sockeye across the Columbia Basin ultimately could be lost. Nowhere is likely to be hurt more than the Okanogan, home to the vast majority of the population.

Of the more than 400,000 sockeye once projected to reach the Brewster Pool, where the two rivers meet, biologists say fewer than 180,000 have made it past the nine dams that interrupt the Columbia between Brewster and the Pacific Ocean. Taking into account fish likely caught here before a fishing closure was ordered last week, as few as 30,000 are expected to make it all the way to their spawning grounds, north of Lake Osoyoos in British Columbia.

“If they don’t make it,” said Chris Fisher, a fisheries biologist with the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, many of whose members live near the rivers’ confluence, “they’re going to perish.”

Perish without spawning, that is.

If there is a silver lining, Fisher and other experts say, it is that two decades and billions of dollars spent to improve fish passage — including improving fish ladders at dams, increasing water flow and restoring habitat — have helped revive the sockeye population, which dwindled to between 30,000 and 50,000 fish entering the Columbia at times in the mid-1990s.

“It would have really been dire if the runs were really low,” Fisher said. “You wouldn’t have as many fish to sacrifice, so to speak.”

This year’s conditions align with what some projections say climate change could do to the Columbia Basin in the future. Dams on the river make matters worse by creating large bodies of slack water that get hot in the sun.

“We’re expecting these types of events to be more frequent,” said Russell Bussanich, a fishery biologist with the Okanagan Nation Alliance, a tribal group in Canada that leads recovery programs for the Okanogan River (spelled Okanagan north of the U.S. border). “Between now and 2050, fisheries managers will have to change the way we do things on both sides of the border.”

Bussanich said solutions in the future could include closing recreational fisheries more often and even trucking fish from the lower Columbia up to Canada. Transporting juvenile fish downstream is already common on the Columbia’s largest tributary, the Snake River, where sockeye are listed as an endangered species and need help clearing the river’s many dams. Elaborate and expensive restoration efforts have helped their populations grow, but this year experts expect a stark decline.

More than 4,000 Snake River sockeye cleared the first dam on the Columbia, the Bonneville Dam, in this spring’s run. But as of Friday only 379 had cleared Lower Granite Dam on the Snake — and just a single fish had reached the final destination, Redfish Lake Creek near Stanley, Idaho, 900 miles from the sea.

Russ Kiefer, a fisheries biologist with the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, said more fish should complete the trip by early September, though the numbers are expected to be very low. Just two cleared Lower Granite Dam on Wednesday, followed by two on Thursday, down from double-digits the week before. Fishery workers quickly scooped up the fish and transported them to a hatchery near Boise with the goal of preserving their genetic footprint and ensuring they spawn.

“Clearly, if we started out with 4,000 and we got 379 at Lower Granite — and things are slowing down — things are going to be bad,” Kiefer said.

The sockeyes’ layover in the Brewster Pool is usually brief. They typically travel up the Okanogan River in pulses, waiting for water that is below about 70 degrees. This year, that “thermal barrier” has eased only a few times, creating what for a time was a strong sockeye fishery.

“If you haven’t ever fished the Brewster Salmon Derby, this would be a good year to do it,” Dave Graybill, known as the “Fishin’ Magician,” wrote in his July 20 report. “In addition to the excellent numbers of summer-run chinook there are huge numbers of sockeye in the Pool.”

Just a few days later, though, the state closed the sockeye fishery here. Chinook can still be caught in this year’s competition because they are much larger and better able to tolerate the warm water.

This week, temperatures in the Okanogan River neared 80 degrees. What fish there were, Bussanich said, are probably dwelling in cool water at depths of 55 feet or more, trying to hold out for a storm or a break in the weather that cools the river. But the internal compass that leads salmon to the same spawning areas generation after generation will inevitably drive them up river.

“At some point they’re going to have no choice,” he said. “They’re going to go for it and it’ll be a do-or-die situation.”

This story was prepared under a grant from the Society of Environmental Journalists’ Fund for Environmental Journalism.

MORE ON DROUGHT:

Shrinking Colorado River is a growing concern for Yuma farmers — and millions of water users

Oregon state agencies told to conserve water as drought worsens

Lake Mead hits a new low, but the drought has a silver lining -- tourism

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.