The dark, complex history of Trump’s model for his mass deportation plan

- Share via

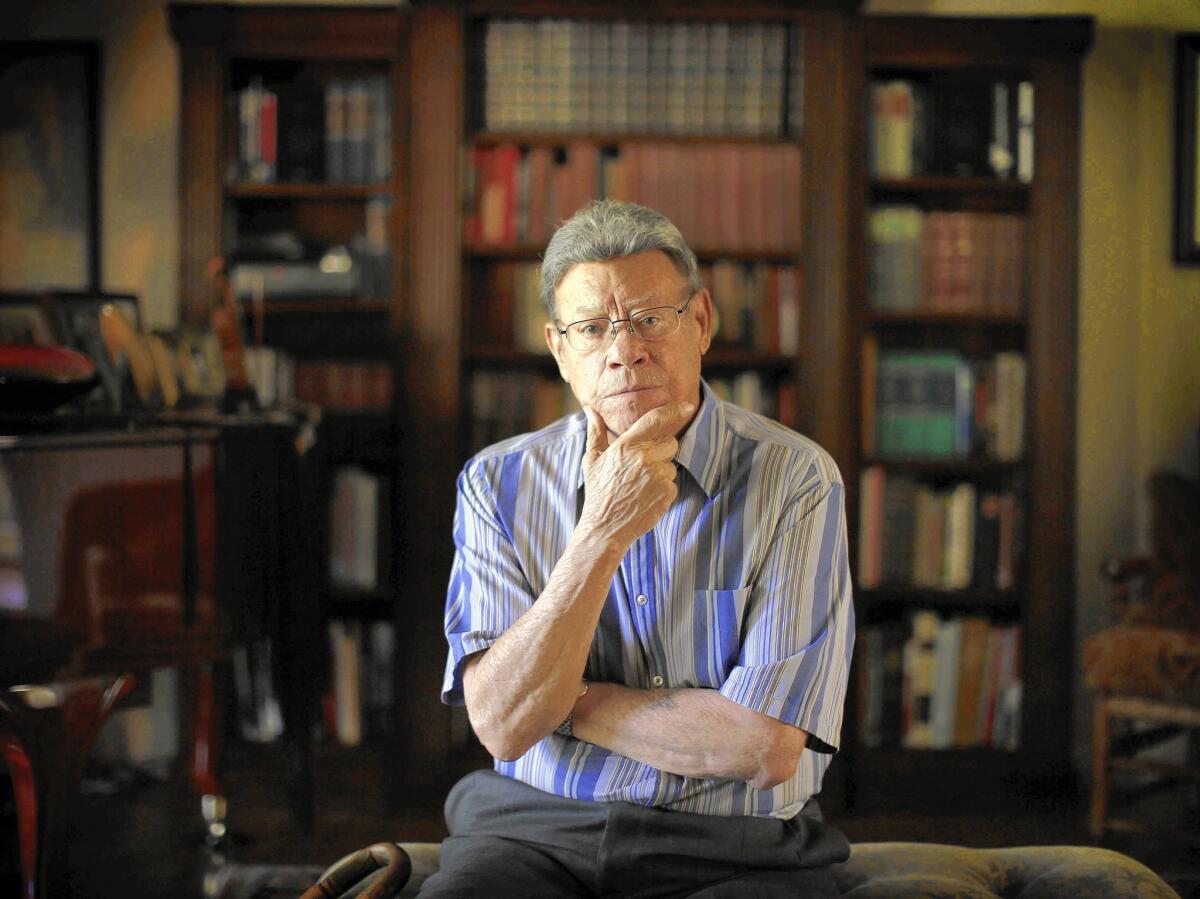

Esteban Torres was 3 years old when his father was sent back to Mexico by U.S. immigration authorities.

“One day, my father didn’t come home,” remembers Torres, who lived with his family in a mining camp in Arizona at the time. “My brother and I were left without a father. We never saw him again.”

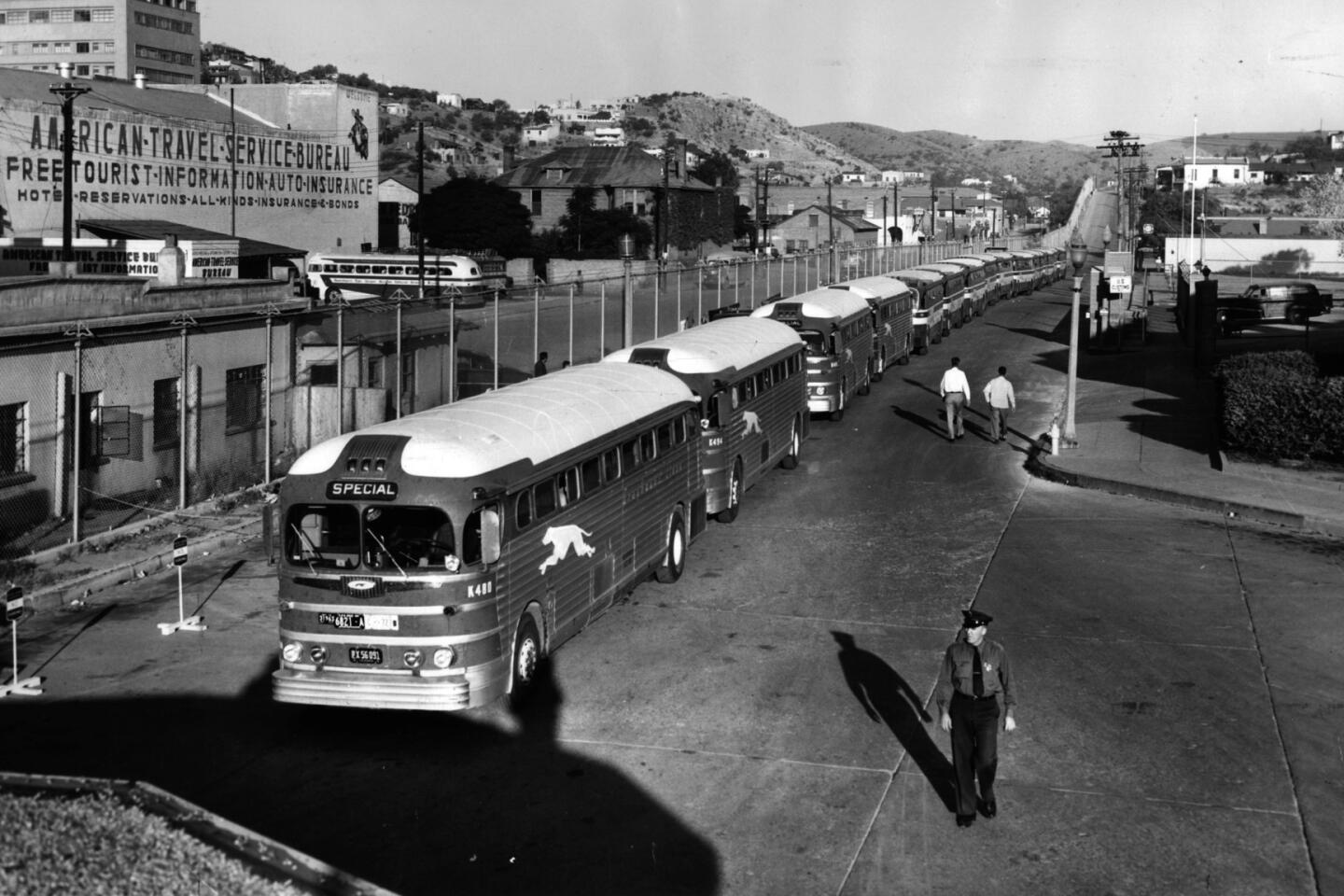

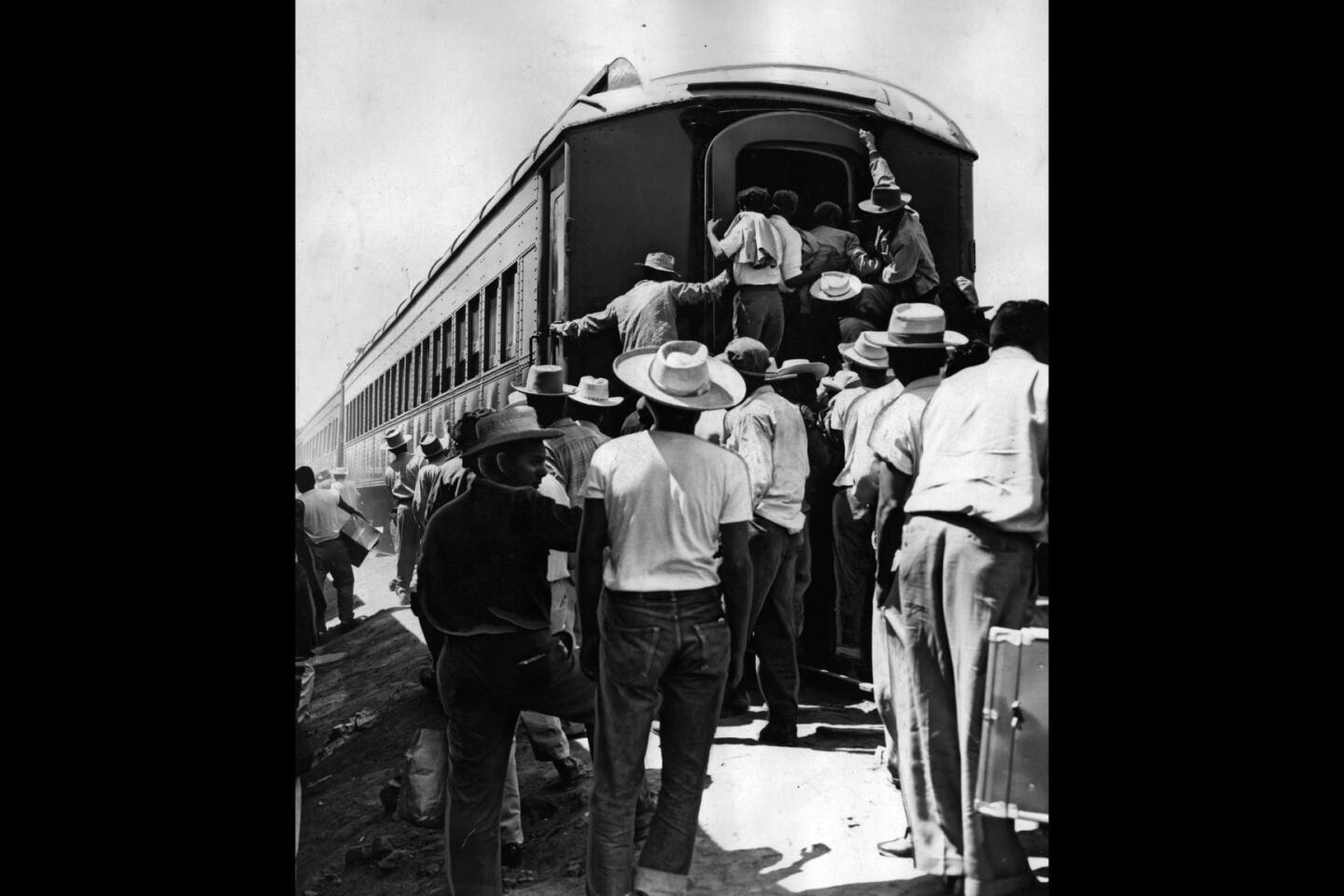

Torres, 85, who went on to become a congressman representing the Pico Rivera area, was part of a generation of people whose lives were changed dramatically by large-scale deportation campaigns during the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s in which millions of Mexican nationals were rounded up and sent across the border on buses, trains and ships.

During Tuesday night’s Republican debate, Donald Trump hailed one of those campaigns — the Eisenhower administration effort known by the outdated, racist name Operation Wetback — as a model for the “deportation force” he says he would deploy to swiftly remove the estimated 11 million immigrants living in the U.S. without legal status.

“They moved 1.5 million out,” Trump said, responding to rivals who said his plan would not work. “Dwight Eisenhower, good president, great president, people liked him,” achieved it, he said.

The record, however, portrays a darker and more complicated picture, suggesting that a mass deportation effort many times larger than any conducted before would be much harder than Trump indicates.

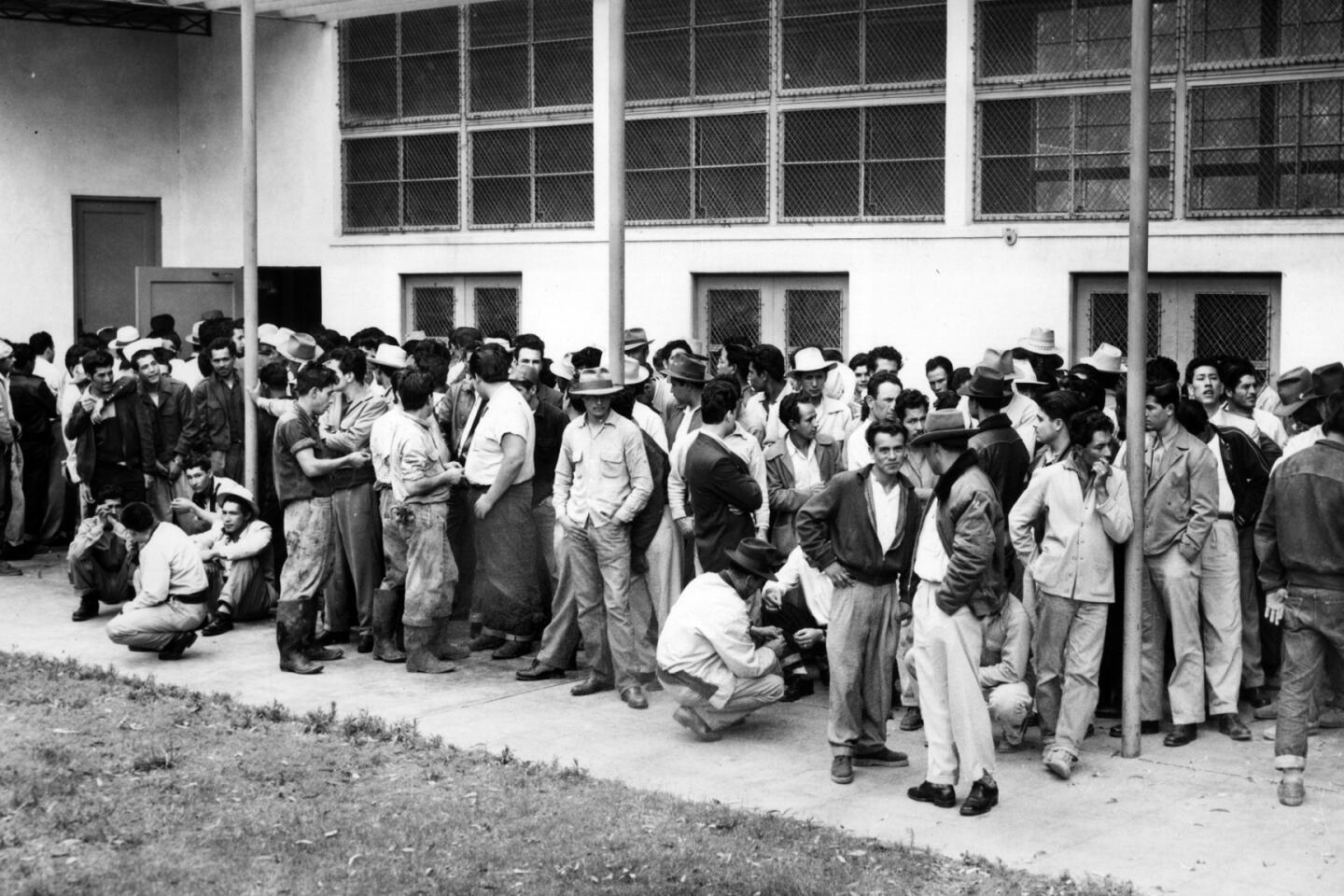

The Eisenhower-era operation deported closer to 300,000 people, according to historians, and was accompanied by scores of deaths and shattered families. In some cases, U.S. citizens were apprehended and deported alongside unauthorized immigrants. Raids were concentrated in border communities but stretched as far north as St. Louis.

In the pre-civil rights era, few spoke up on behalf of the immigrants, historians say.

Some of those apprehended in the raids were allowed to become legal residents by signing up for work programs. Others were sent back to Mexico, often in overcrowded ships or trains.

In one incident, deportees on an overcrowded ship in the Gulf of Mexico rioted; five drowned.

Mexican immigration authorities, under pressure from farm owners in their own country to slow emigration to the U.S., which was depleting their labor force, often forced arriving deportees to board trains that took them deep into the Mexican interior.

One day, my father didn’t come home. My brother and I were left without a father. We never saw him again.

— Esteban Torres, whose father was deported when he was 3

“It was very inhumane,” said Mae Ngai, a professor of history at Columbia University who has documented dozens of deaths from that era, including 88 people who died from heat exhaustion while being deported.

Though the program did increase the ranks of legal immigrant workers, it didn’t halt illegal immigration, she said.

“They didn’t stop it,” Ngai said. “They lessened it temporarily, but they didn’t stop it.”

The goal of the Eisenhower-era program and earlier deportation efforts was not simply to remove immigrants in the country illegally, but to push them to gain legal status, said Kelly Lytle Hernandez, a professor of history at UCLA who has written about the deportations.

At a time when the U.S. and Mexico were promoting a guest-worker system for agricultural workers, “this was about frightening employers and the immigrants into getting with the program,” she said.

While many immigrants in the country illegally were deported under the program, many were also granted work permits so they could stay, she said. That’s an aspect of the program left out by Trump, who has not proposed increasing opportunities for legal immigration to the U.S.

“He doesn’t know the full history,” said Hernandez, who called Trump’s proposal “a fantasy.”

Like today, U.S. authorities in the early and middle parts of last century faced a conundrum. Farm and business owners demanded cheap labor, and immigrants from Mexico were willing to supply it. But authorities on both sides of the border wanted some semblance of control.

They tried to exert it with the Bracero program, a series of agreements between the U.S. and Mexican governments, beginning in 1942, that allowed Mexicans to work in the U.S. on short-term contracts. But many employers skirted the law, preferring to hire less expensive laborers who crossed the border illegally.

The U.S. conducted periodic deportation campaigns as early as the 1920s, according to Ngai. In the 1950s, tensions reached a peak.

Warning against an “invasion” of unauthorized immigrants from Mexico, the head of the agency then known as the Immigration and Naturalization Service initiated Operation Wetback in 1954.

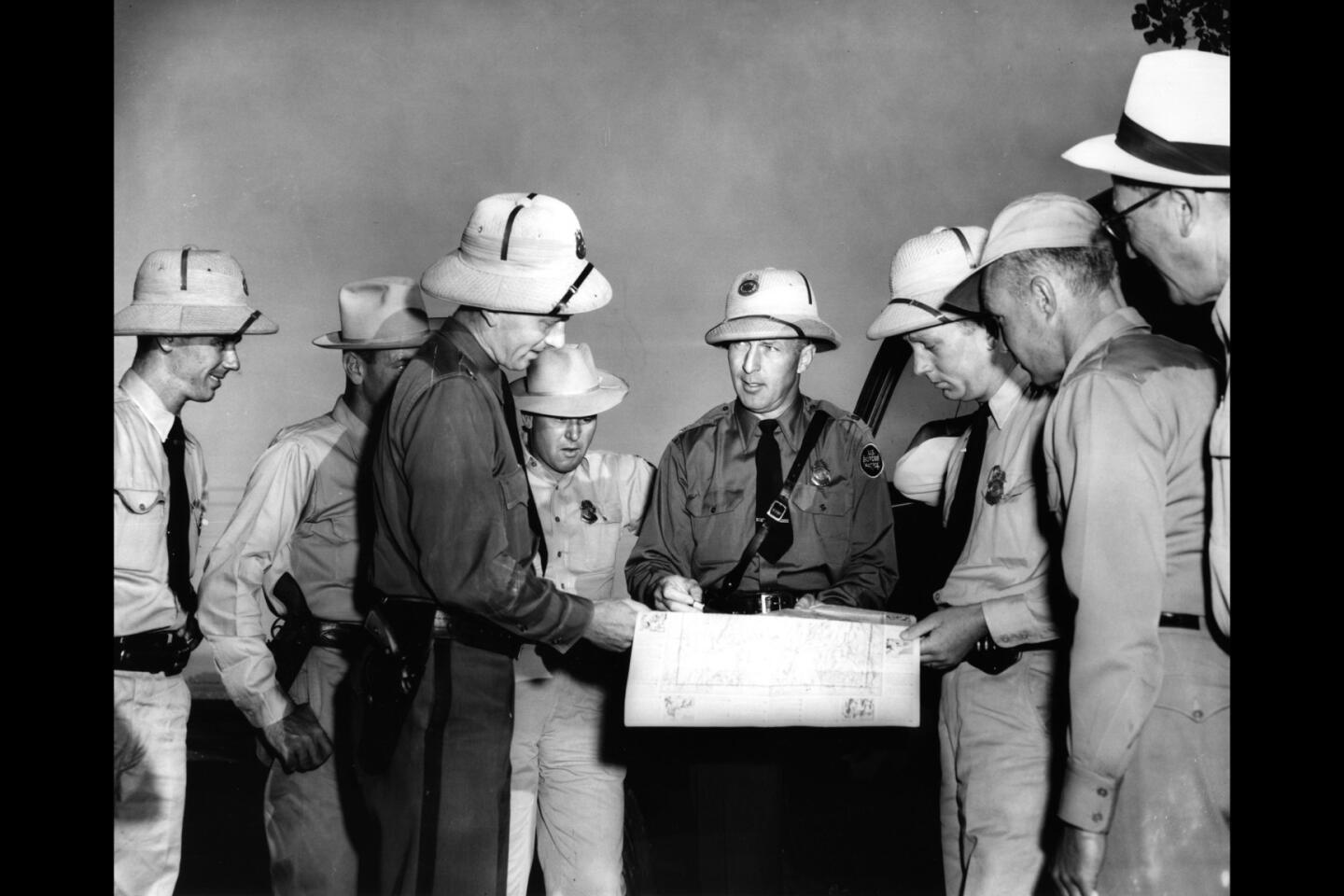

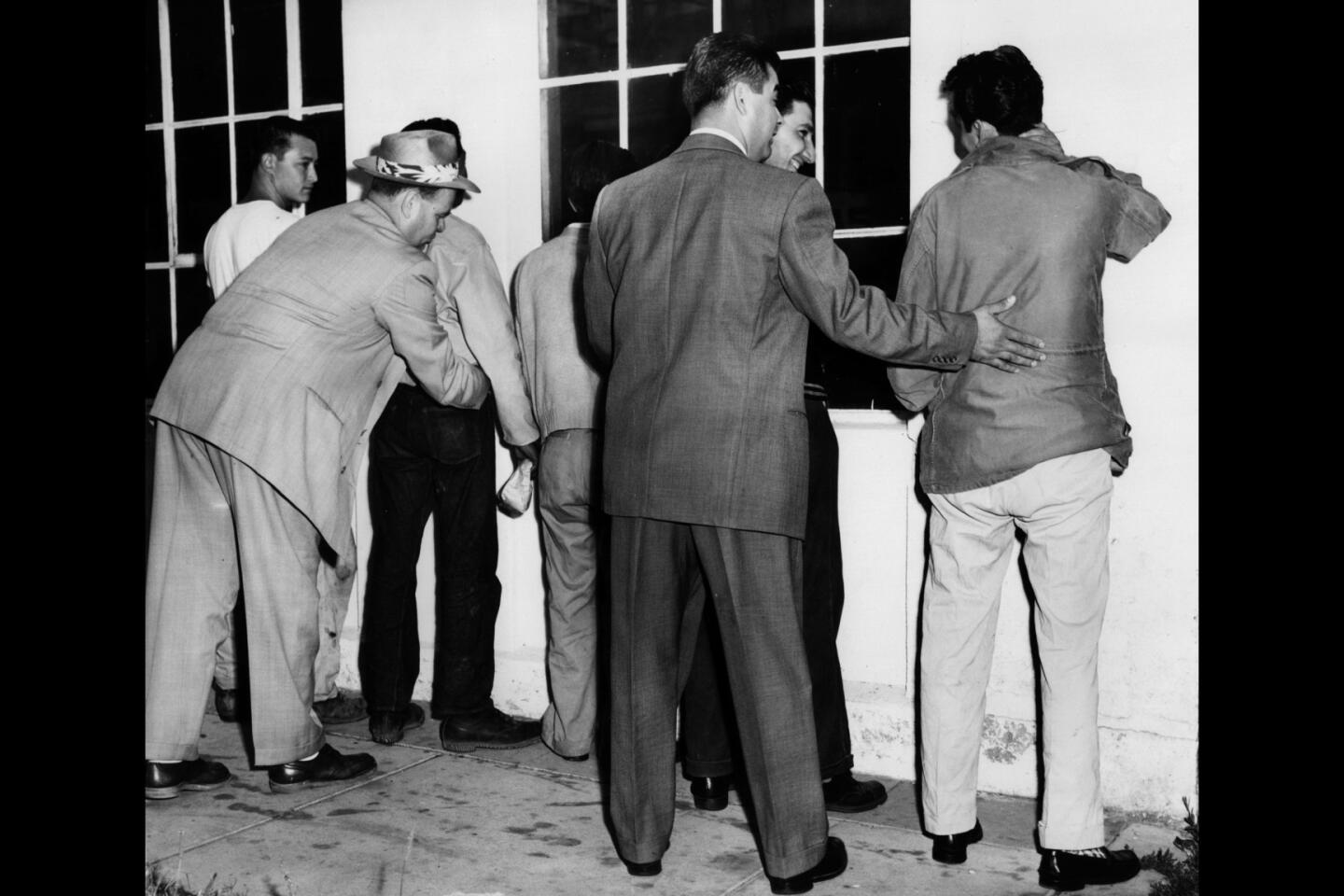

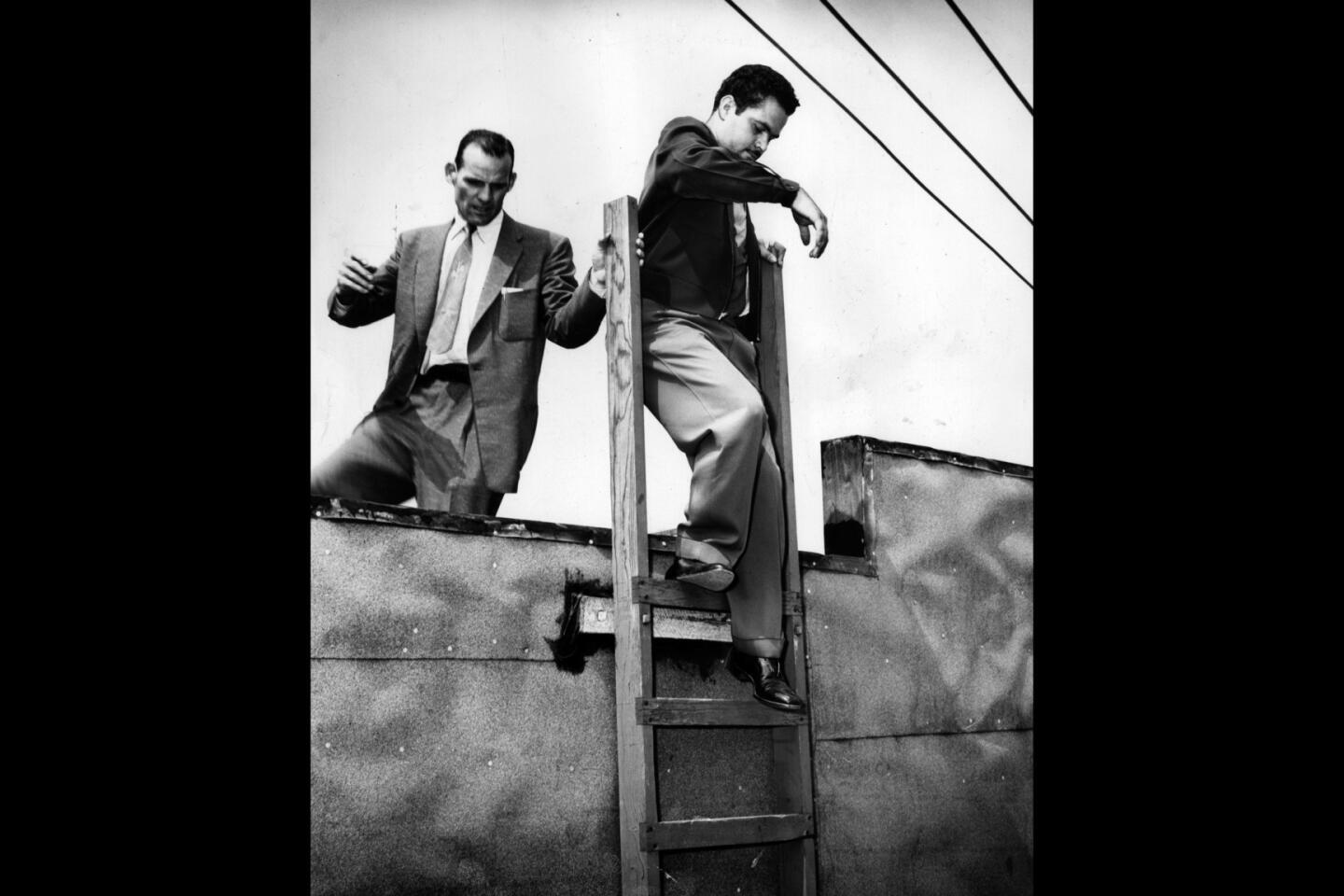

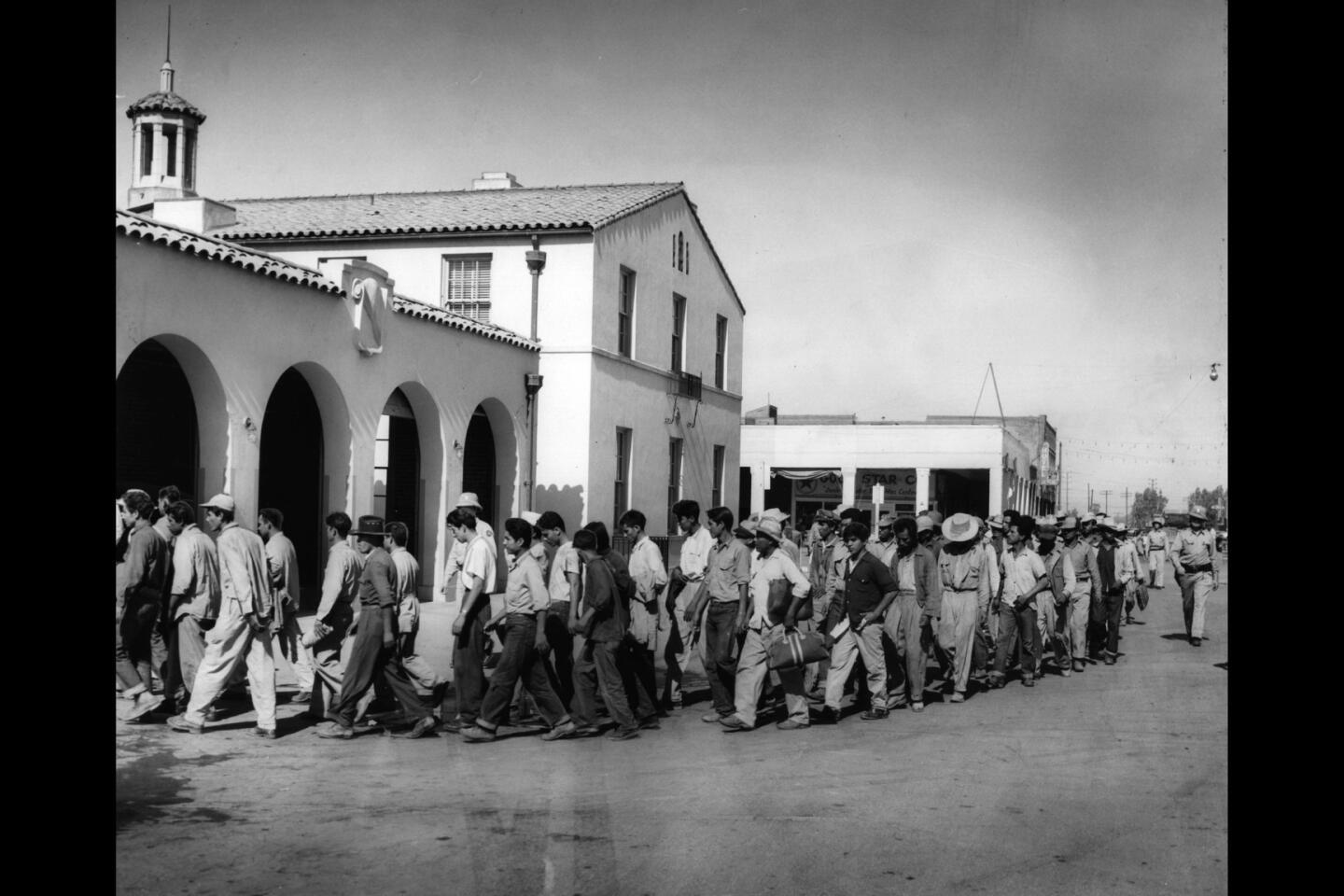

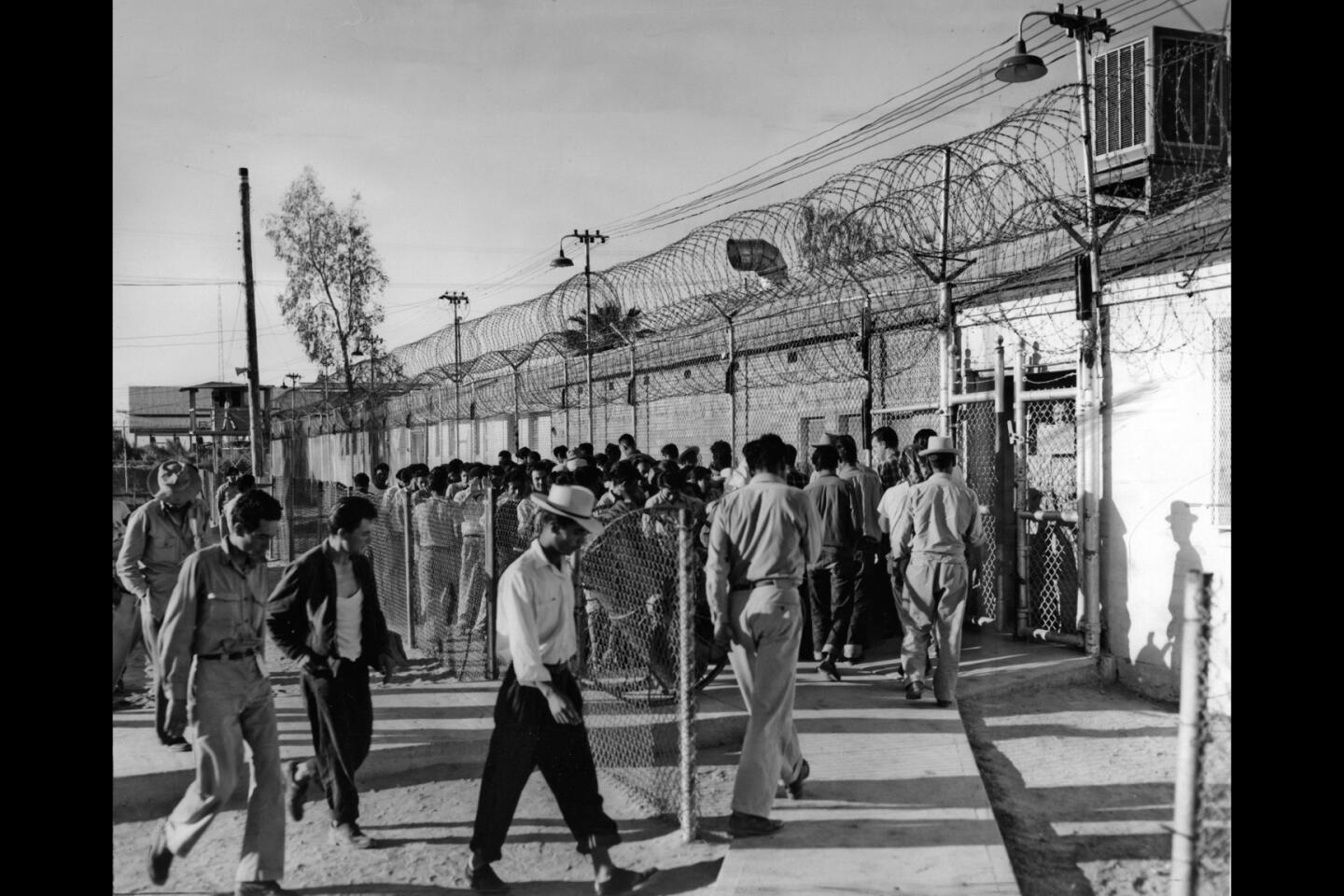

According to Ngai, “the project was conceived and executed as though it was a military operation,” with 800 immigration agents fanning out across the Southwest, apprehending as many as 3,000 immigrants a day at roadblocks and in raids on homes, farms and factories.

Front-page Los Angeles Times headlines from that time touted the operation in demeaning language considered acceptable at the time. “Wetbacks Herded at Nogales Camp,” reads one. “U.S. Patrol Halts Border ‘Invasion,’” reads another.

Veteran farmworker organizer Dolores Huerta remembers the deportation campaign vividly.

At the time, she was living in Stockton, where her mother owned a motel. She recalls immigration agents raiding the hotel and the movie theater across the street.

“They would show up and check everybody,” said Huerta, whose family members were U.S. citizens. “My mom used to say, ‘Tell them you need to see a search warrant.’”

“It was terrible,” said Huerta, adding that the raids sowed fear in the community and helped drive her to join the fight for immigrant farmworker rights.

Esteban Torres, in his West Covina home, holds a photograph of his father, who is at far right.

Torres, whose father was removed to Mexico in one of the early deportation campaigns, said his father eventually came back to the U.S. But by then, Torres and his mother had moved to East Los Angeles.

He knew nothing about his father’s life or whereabouts until 20 years later, when he received news that his father had died.

Twitter: @katelinthicum

ALSO

‘Buy a lady an overpriced drink?’ L.A. police say bar scam is widespread

El Niño is here, and it’ll be ‘one storm after another like a conveyor belt’

Inca boy’s DNA shows how humans spread to South America

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.