Trick or treat for science: Kids become test subjects

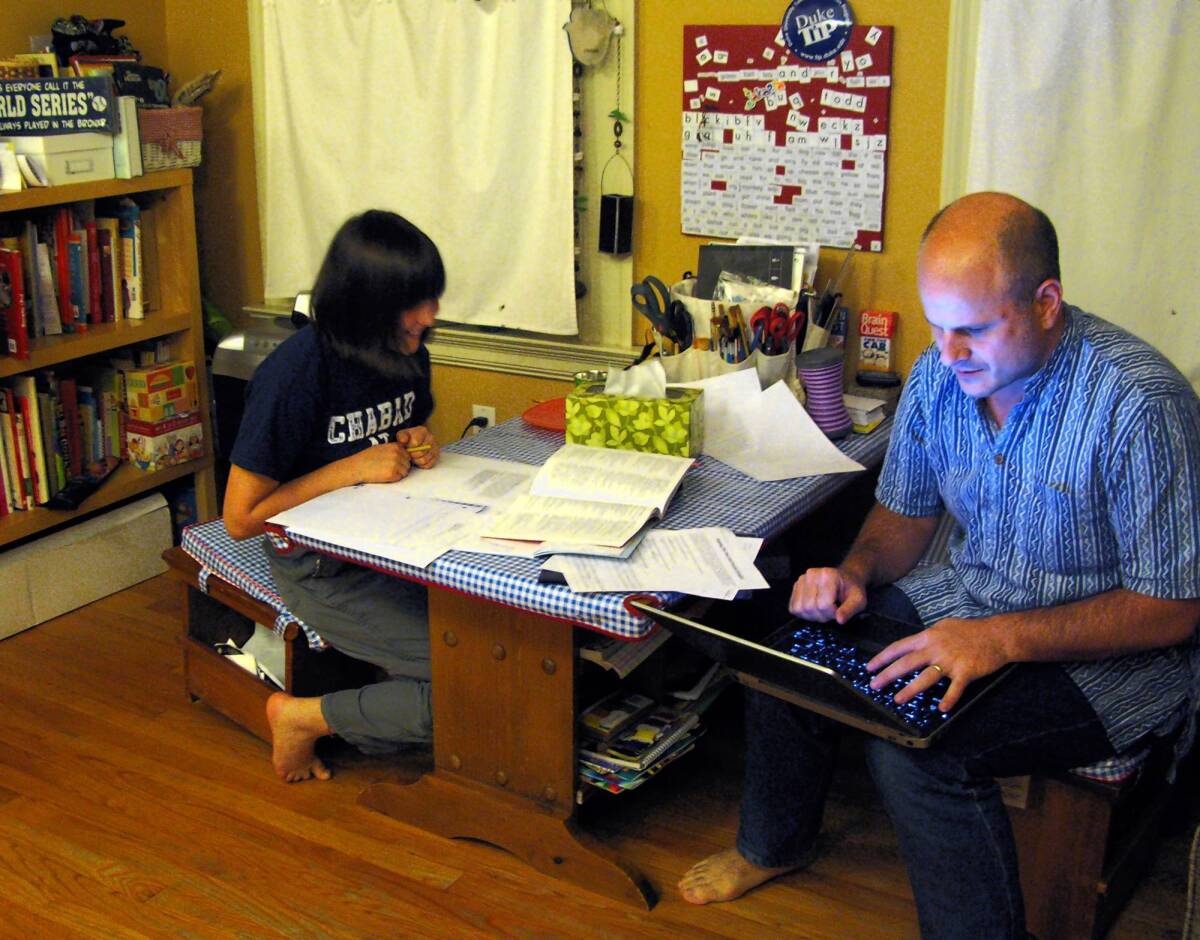

NEW HAVEN, Conn. — Each year, Halloween is a massive operation at Dean Karlan’s house, drawing in members of his family, particularly his 13-year-old daughter, Maya.

Maya’s enthusiasm for Halloween knows few bounds. She makes her own costumes: a castle with a working drawbridge, a full-color traffic light with a flashlight inside to switch signals. She’s been known to spend the whole year thinking about her next get-up.

“Normally I plan my Halloween costumes the day after Halloween,” Maya said. “I get very excited.”

FOR THE RECORD:

Halloween research: An article in the Oct. 31 Section A about researchers who use Halloween trick-or-treaters as test subjects for behavioral science experiments said that Stonehill College is in Connecticut. It is in Massachusetts.

But this year, the bubbly eighth-grader is giving up her trick-or-treat time — and her idea of dressing as a toaster — to help out at home, where the real action is.

At Maya’s house, the children marching inexorably through the darkness toward the promised candy will get their treats. But as they climb the creaking stairs of the Karlans’ porch, they’ll also do something else: become test subjects in a one-night science experiment.

No need to be spooked. Karlan, a Yale University behavioral economist, just taps into a rare study population with a guaranteed turnout: trick-or-treaters.

For seven years, hundreds of children have been lining up in front of his home to answer questions from clipboard-carrying college students, and then choose their candy. Though they may not realize it, the answers they give and the sweets they pick offer the scientists fresh insight into theories about children’s thinking, development, even their politics.

Ninth-grader Cole Benoit lives down the street. He’s been subject to three rounds of experimentation over the years, and thinks it’s fun.

“It’s kind of like a game,” he said.

::

Most studies about Halloween focus on some aspect of the holiday — mostly on common fears, such as the rate of pedestrian deaths that day or the perceived dangers of candy.

But very few actually use Halloween as a platform to study economics and behavior, even though it’s a unique opportunity to do so, said Dan Ariely, a behavioral economist at Duke University who has done some trick-or-testing of his own.

“The benefit of Halloween was that the kids came to us rather than we having to go to them, and we were doing it in a natural environment that fits in their lifestyle and mode of thinking,” said Ariely, who published a 2007 research paper that used trick-or-treaters to study the irrational decisions people make when it comes to getting “free” goods.

“It’s a great opportunity for data. The only thing it requires is that you will have a house where the kids come to visit,” he said, “and the adults are not too suspicious.”

At the Karlans’ home, each year is different. Last year’s study found that 38% of kids 9 and older who saw a poster of First Lady Michelle Obama chose fruit instead of candy — twice as many as those who made that choice after seeing Ann Romney, wife of 2012 Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney. The study indicated that the first lady’s “Let’s Move” campaign, promoting healthy living for children, appeared to be reaching its target audience.

Earlier years have been more abstract. A 2008 experiment, which asked kids to choose between either transparent or opaque bags of candy, found that children with more generic costumes preferred the see-through bags — that is, they avoided ambiguity.

This year, the study aims to test whether some children are inherently planners — whether they planned their costume ahead of time or procrastinated until the last minute, and whether they have a plan for how they will eat their candy. They’ll weigh their answers against whether kids choose fruit or give into the easy temptation of candy.

Opinions differ as to whether a child’s discipline in one answer means the same will apply in the other two. One of Karlan’s partners this year, economist Jodi Beggs of Northeastern University, meticulously rations out her candy but throws her costume together at the last minute.

“You would really hurt this prediction,” Karlan told her in a conference call to get ready for the big night.

“You have to save the best candy for last!” Beggs replied. “You can’t waste it at the front.”

Though she can’t participate in the study, Maya seems to really fit with the hypothesis: She plans her costume, rations her candy out for months and has been known to choose the healthier option.

“She’s incredibly well-disciplined,” Karlan said. “When she’s given her choice of candy or fruit, her choice is typically fruit. She’s totally not me when it comes to food.”

Regular test subjects seem intrigued by each year’s challenge.

“I think it’s the most interesting, because you actually get to do stuff, and at the other houses you just go and get candy, and just move on,” said seventh-grader Claire Turner, who lives across the street and has participated in several experiments.

The Karlans’ quiet neighborhood in New Haven is a Mecca for trick-or-treaters, though it’s not immediately apparent why — there are no haunted houses on this block, no inflatable ghosts on the lawn or pop-up cadavers in entryways.

“This is as decorative as we get,” said Karlan’s wife, Cindy. “Once we carve the pumpkins, we’re done.”

Residents say the area’s popularity is because the houses are so close together, minimizing the door-to-door travel time for trick-or-treaters. They come in droves, said Claire’s father, Paul Turner, Yale’s chairman of ecology and evolutionary biology.

“It’s pretty amazing how year after year he does this — it attracts a big crowd and it’s pretty creative,” Turner said. It may even draw a decent cross-section of the city population, he added. “A lot of people come in just for that night, from all over the city, and they trick-or-treat here and go back to where they came from.”

Of course, popularity comes with its own set of problems for researchers.

“There is a bit of chaos,” Karlan said. “You don’t get the same amount of control you get in a laboratory setting.”

This year, Karlan and his team will have to carefully control the flow, to make sure children aren’t influenced by answers they hear from other kids while waiting in line. In a conference call, the researchers discuss possibly lining up chairs and using ropes to narrow the porch to a one-person entrance. That way, other kids in line won’t bunch together and overhear their peers’ answers.

The whole hectic night gives college students valuable hands-on experience in designing and conducting an experiment in real life, said Bonnie Klentz, a social psychology professor at Stonehill College in Connecticut who was not involved in Karlan’s work.

In the 1970s, Klentz worked on a Halloween experiment testing whether trick-or-treaters would grab extra candy if they were alone in a room — but facing a mirror.

The results were striking: The mirror had no effect on younger children who saw their own reflections, but it made older kids less likely to grab candy — a hint that self-awareness grows as children develop.

But running such one-night operations comes with a hitch, Klentz added: You only get one shot.

In Klentz’s case, the researchers realized they should have asked each child’s age, “so we had to wait until the next Halloween to run a second study,” she said.

Asked whether that risk ever worries Karlan, the economist laughs. His day job is more focused on poverty initiatives; this is just a side project he does for fun, one that gives students some hands-on training in running an experiment.

“I think the biggest difficulty in some sense is the struggle about how seriously to take it all,” Karlan said.

Karlan has submitted Halloween-based papers for publication in scientific journals. He’s trying again with a paper on experiments that found that older children would change their stated political party loyalty if it meant getting a little more candy. Younger children, however, could not be bribed, and remained steadfast.

“I think that tells an interesting story about children and politics,” Karlan said.

But when he’s submitted papers to journals in the past, they’ve gotten one of two responses, he said.

“We’ve either been told, ‘You didn’t produce enough knowledge, it wasn’t a clean enough test of a theory,’ or that the paper isn’t funny enough,” Karlan said. “And personally, I was far more insulted by the second criticism.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.