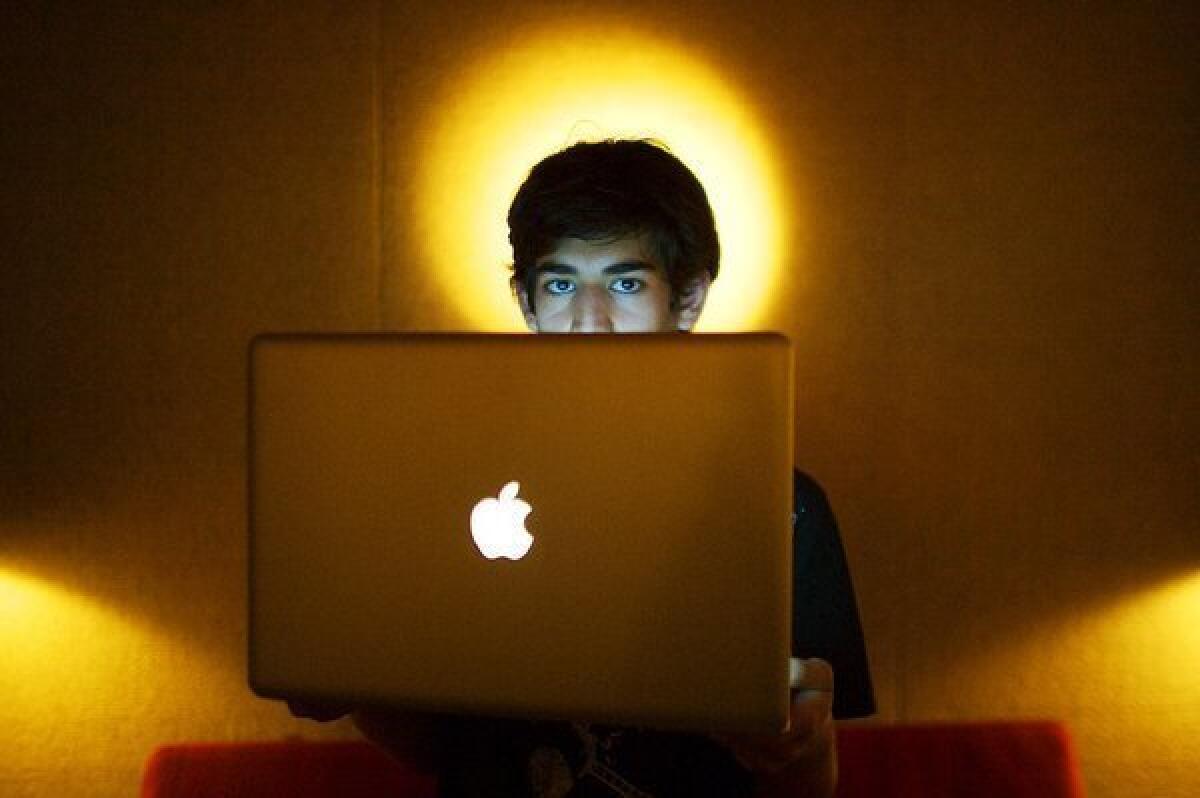

Aaron Swartz’s father on U.S. attorneys: ‘They destroyed my son’

When Aaron Swartz was 3, he taught himself to read. When he was 4 or 5, he could read the New York Times, his father says.

When Aaron was 14, he invented the software behind RSS, the information distribution service. Five years later, he started a project that would turn into Web news and entertainment behemoth Reddit.

And in an interview with the Los Angeles Times from Chicago on Thursday, Bob Swartz said his son “was hounded to his death by a system and a set of attorneys that still don’t understand the nature of what they did. And they destroyed my son by their callousness and inflexibility.”

Aaron Swartz, 26, committed suicide by hanging in his Brooklyn apartment last week as he faced a federal trial for what he saw as a political act: In 2010, he physically entered the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to set up a computer hack that would download millions of academic articles from JSTOR, a nonprofit database service. The research had often been paid for with taxpayer funds, he wrote in a 2008 manifesto, so the information should be available to the public.

Swartz faced 13 felony counts, including wire fraud, and the possibility of years in prison. By the time of his suicide, JSTOR had released more than 4 million of the articles online for free, but the trial was still on.

“In this instance, when the people who destroyed the financial system go free, to think that they were charging Aaron in this way displays a complete miscarriage of justice,” Bob Swartz told The Times.

On Wednesday night, the U.S. Attorney’s office in Massachusetts broke its silence over the Swartz case. A statement from U.S. Atty. Carmen M. Ortiz extended “heartfelt sympathy” to Swartz’s family and supporters but held firm on the office’s stance that Swartz should serve at least six months in prison. Her prosecutors handling the case, she said, had acted “reasonably.”

“The prosecutors recognized that there was no evidence against Mr. Swartz indicating that he committed his acts for personal financial gain, and they recognized that his conduct -- while a violation of the law -- did not warrant the severe punishments authorized by Congress and called for by the sentencing guidelines in appropriate cases,” Ortiz said in the statement.

“That is why in the discussions with his counsel about a resolution of the case this office sought an appropriate sentence that matched the alleged conduct -- a sentence that we would recommend to the judge of six months in a low-security setting.”

Swartz’s attorney, Elliot R. Peters, portrayed the prosecution as taking a tougher stance on a plea agreement that could have avoided a trial.

“When I took over the case, which was last fall until now, the prosecutors had the exact same position, and here’s what it was: It was an either/or,” Peters told The Times on Thursday.

He said Swartz could either plead guilty to 13 felonies and agree to a four-month prison sentence, or plead guilty to 13 felonies on the condition that prosecutors ask a judge for a six-month sentence, and maybe Swartz could get less.

If the case went to trial and Swartz were convicted, Peters said, prosecutors said he would face a sentence greater than seven years. “I said to them, ‘How about a misdemeanor and probation?’ And they said, ‘We will never not be seeking a prison sentence in this case.’”

The possibility of prison loomed over Swartz, his girlfriend has told The Times, as well as the prospect of asking friends and supporters for money to fight the charges. In the week before his suicide, he’d also had the flu, Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman, 31, said. But he didn’t know that his attorney had failed to secure a better plea deal from prosecutors, Peters said.

Bob Swartz also dismissed the notion that his son had a depressive personality.

“He had never been diagnosed as having depression; he was never on medication for having depression,” Swartz said.

Aaron Swartz’s mother had been hospitalized in December 2011 after having a bowel obstruction and going into septic shock, Bob Swartz said. She spent several weeks in a coma, four months in intensive care, and two more months in the hospital.

“So the notion, the narrative that people are going to say -- is that he’s somebody who just has depression -- is just wrong. You’d be depressed too if you were under a 13-count federal indictment and you go see your mother, who’s in a coma.”

Bob Swartz also said that records gathered by the defense during trial preparations showed that large, automated downloads like Aaron’s -- called “spidering” -- happen at MIT “on a regular basis.”

“In the discovery materials we received from the federal government, they described as happening on a monthly basis, approximately -- individuals downloading large amounts of data from journal websites,” he said.

Peters couldn’t confirm that detail, saying that other workers in his office were the ones looking through those records. MIT officials, who are conducting their own investigation into the university’s role in the case, declined to comment. Peters said MIT had improperly allowed federal prosecutors access to Swartz’s computer without a subpoena or warrant.

Orin Kerr, a George Washington University law professor and an expert on computer crime, said in a blog post Wednesday that he believed prosecutors had not overreached in their charges or in calling for prison time for Swartz, who Kerr said was trying to change a bad policy undemocratically. Kerr said the prosecution’s bargaining tactics were also nothing new.

“These sorts of tactics have been going on for years, without many people paying attention,” Kerr wrote. “If we don’t want a world in which prosecutors have these powers, we shouldn’t just object when the defendant in the cross hairs is a genius who went to Stanford, hangs out with Larry Lessig, and is represented by the extremely expensive lawyers at Keker & Van Nest.”

When asked what he wanted the public to know, Bob Swartz fell silent. After a few moments, he replied: “That the evidence showed clearly that Aaron did not break the law, that the network was open, that access was not unauthorized by MIT, and that he was not guilty of any crime.”

He added, “No one was harmed, no one was damaged.”

ALSO:

Businessman gets 14 years for role in terrorism plots

Aurora shooting: Theater to reopen today, sparking outrage

Dug from avalanche by boyfriend, woman recalls ‘sliding face-first’

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.