Not right the first time, Lincoln wrote this Gettysburg Address twice

There will be no shortage of events marking Tuesday’s 150th anniversary of the Gettysburg Address, but one of the most surprising ones will take place hundreds of miles from where Abraham Lincoln delivered his historic and mercifully brief speech: at Cornell University in New York.

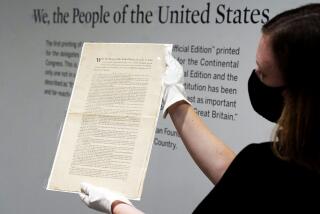

The university in Ithaca, N.Y., possesses one of only five known original copies of Lincoln’s address. To honor the anniversary of the day Lincoln gave the speech in Gettysburg, Pa., Cornell has put its rarely seen copy on display through Saturday.

“There’s nothing that can compare to seeing this paper, held by Lincoln, and written out so beautifully in his hand,” said Michele Hamill, a conservator at Cornell, who detailed just what goes into preserving such a delicate document.

When the speech is not on display, which is most of the time, it is stored in a tightly secured, climate-controlled vault designed to protect it from water, fire and just about anything else that might damage the linen-based paper on which Lincoln wrote.

For display purposes, the paper was placed between two sheets of UV-filtering Plexiglass. A specially constructed frame surrounds the Plexiglass. A special screwdriver is needed to deconstruct the frame and get to the Plexiglass and the paper enclosed within it.

As long as the document is on display, a Cornell police officer will stand guard next to it.

So how did this version end up at Cornell, and how did it survive all these decades despite changing hands at least five times?

As Hamill explains, it was not an easy path. It began when a historian named George Bancroft asked Lincoln for a copy of the Gettysburg Address manuscript, long after the speech had been given. Bancroft planned to reproduce it for sale to raise money for wounded soldiers.

The first version that Lincoln sent Bancroft was not usable, because the president -- perhaps in an effort to not waste the high-quality paper he used -- wrote on both sides of a single sheet.

Technology did not permit reproducing double-sided copies, so Bancroft asked Lincoln to do it again, this time using two pieces of paper.

Again, the president complied, and he sent Bancroft what he needed. That version is now in the White House.

The double-sided version became known as the Bancroft Copy, and the historian willed it to his grandson, Wilder Dwight Bancroft, who was a Cornell chemistry professor. Sometime during the Great Depression, the grandson sold the paper to a New York City dealer.

“We can assume he needed some money,” said Hamill.

The dealer who bought the manuscript took care to protect it. He had a leather portfolio constructed just to hold the paper. He even placed a sheet of cellophane over the paper, thinking this would ensure the document remained untarnished.

The opposite was true. The covering actually caused some darkening of the paper, but not enough to ruin the manuscript, which in 1949 was gifted back to Cornell.

“Just think about it -- he had secretaries, yet he wrote it out himself,” said Hamill of Lincoln. “You could easily have delegated that work to other people, but he did it.”

Hamill is equally impressed with the various keepers of the document.

“We’re thrilled it made this unusual journey from all these different people, who for the most part have been excellent caretakers,” she said. “Even the dealer who put the cellophane on it did it with the best intentions.”

ALSO:

Methodist pastor married gay son ‘in good conscience,’ now on trial

Colorado proposes reducing methane leaks from energy production

New Mexico investigates police who shot at van fleeing with mom, kids

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.