Overdosing on heroin: This drug can bring them back

Even the threat of death can’t reliably stop a heroin addiction.

Paramedics tell stories about the tricks addicts use to save themselves from an overdose -- that is, to ensure that somebody else saves them. For instance, users will block a water drain in a public building so that someone will notice flooding and call 911.

“Interestingly, we have received several calls for auto accidents,” an Ohio emergency medical technician, or EMT, noted in a state addiction treatment survey published in November. “Apparently, some users are stopping in the parking lot, putting their car in ‘drive’ with foot on brake. They know that if they overdose, the car will roll forward and wreck and this prompts someone to call 911!”

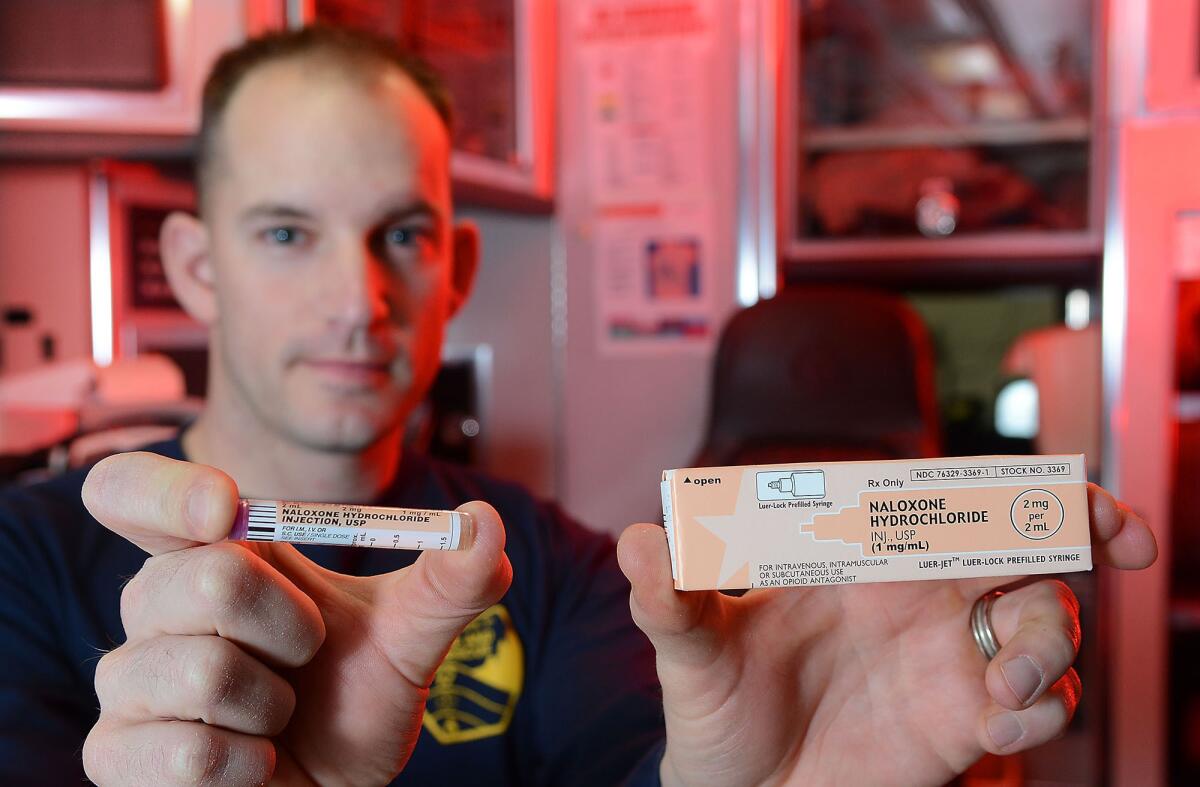

Which is partially why some officials are eager to increase distribution of a highly effective overdose-reversal drug called naloxone. Sold under the brand name Narcan, it could fight the increase in fatalities from heroin’s big return to the national stage.

PHOTOS: Notable deaths of 2014

California greatly expanded the availability of naloxone as of Jan. 1, allowing family and friends of heroin and painkiller users to get the antidote from doctors. The idea is to have the drug at the ready in case a loved one overdoses.

The Network for Public Health Law says California is one of 17 states, plus the District of Columbia, that have adopted such laws.

Ohio’s Legislature is considering a similar measure. Like most of the country, Ohio has witnessed a surge in heroin use reminiscent of the smack crazes of the 1970s and 1980s. Much of the surge, which the Los Angeles Times wrote about in Tuesday’s edition, is driven by pain-pill users switching to heroin, which is much cheaper than oxycodone but has the same primary source -- opium.

Ohio’s bill would broadly expand naloxone’s availability to family, friends and anyone “in a position to assist an individual who there is reason to believe is at risk of experiencing an opioid-related overdose.”

Nationally, according to Drug Enforcement Administration statistics, there has been a 45% increase in fatal heroin overdoses from 2006 to 2010, the most recent data available.

In Ohio, the heroin death rate roughly tripled over the same period, according to state health statistics.

Naloxone counteracts the effects of opioids such as OxyContin and heroin by blocking the receptors in the brain that take in the drugs.

When injected into an overdose victim whose heart is still beating, “it’s virtually 100% effective,” Wilson Compton, deputy director at the National Institute on Drug Abuse in Bethesda, Md., told The Times.

Often, when overdose victims are discovered, “they’re kind of blue, they’re breathing very shallowly, or hardly breathing at all,” Compton said. “If this medication is administered [properly], they wake up within a minute or two. It’s remarkable. You save their life.”

Although naloxone has been around for decades, its availability is often limited by state laws that predate the heroin and painkiller epidemics. Those laws were designed to keep physicians from distributing a drug to someone they hadn’t examined or who wasn’t going to use the medication himself, according to the Network for Public Health Law.

“There’s no good reason naloxone is so underutilized: It’s simply a failure of education and planning,” Lynne Lyman, the California state director for the Drug Policy Alliance, wrote in an op-ed for The Times in April.

“It’s not a narcotic and has no recreational use. You can’t get addicted to it.”

Researchers are still trying to figure out what doses work best to fight off a heroin or OxyContin overdose. A typical first dose starts with at least 0.04 of a milligram and can be injected by needle or nasal spray.

There is some question about whether naloxone has any significant side effects, or whether it simply exposes underlying conditions in drug abusers. One study said that “extremely high doses” of naloxone had been given to non-addicts without any reported side effects.

Research has also shown that addicts may suffer from acute withdrawal symptoms if their overdose ends too quickly, though those effects are not normally life-threatening. Sometimes the effects of heroin outlast the effects of naloxone, requiring another dose.

In Ohio, only some paramedics are allowed to carry Narcan. Nevertheless, its use by the state’s EMTs has nearly tripled over the last decade as heroin’s popularity has surged, according to state officials.

Users are very aware of Narcan, according to EMTs who gave personal accounts to state officials for the November report.

“My agency borders the state of Indiana. Dearborn County, Indiana, does not have Paramedics or Intermediates who can administer Narcan,” one respondent wrote. “People drive to Ohio because they know we have Narcan and can give it to them. This has been told to us many times by patients from Indiana.”

Another EMT wrote: “The numbers are climbing on the amount of overdoses that are from more rural areas coming into our area. We have been told by some of the patients they come to take drugs in our area because ... they can get Narcan quicker because we are on station.”

Lorain County, Ohio, which saw its opioid overdose deaths triple to 60 from 2011 to 2012, has been playing host to a pilot study started in 2013 that would allow police to carry the drug.

When three people died and more than 20 were hospitalized with overdoses over one weekend from a bad batch of heroin, local officials credited Narcan with saving lives. Similar bad batches have killed dozens of users across Pennsylvania and Maryland recently.

In New York, a pilot study that put Narcan in the hands of Long Island police officers was quickly expanded after the Suffolk County Police Department claimed overwhelming success with its program in 2012 and 2013.

Dr. Scott Coyne, the department’s chief surgeon medical director, has been running the Narcan program for 18 months. In that time, he said, the department has saved 172 overdose victims.

“Our officers are typically first on the scene of all medical emergencies and opiate overdoses, and it’s those first minutes that can make the difference between life and death,” Coyne told The Times in a phone interview. “Administering Narcan at that point to an opiate overdose victim has resulted in a dramatic number of opiate reversals and life-saves.”

The saves are also helping put a dent in the county’s fatal overdose numbers, Coyne said.

Opioid overdoses are thought to cost more than $20 billion in losses to the U.S. economy from treatment costs and loss of earnings. Some research has suggested Narcan would cut back the cost of overdose hospital visits and emergency calls.

Not to mention save lives.

“It would make sense for law enforcement [and paramedics] in any location that has appreciable rates of prescription opioid misuse or heroin misuse to be trained or have this available,” said Compton of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. “It can save a life quite easily, and unless you move quickly, it can take a lot of time to get somebody to the hospital.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.