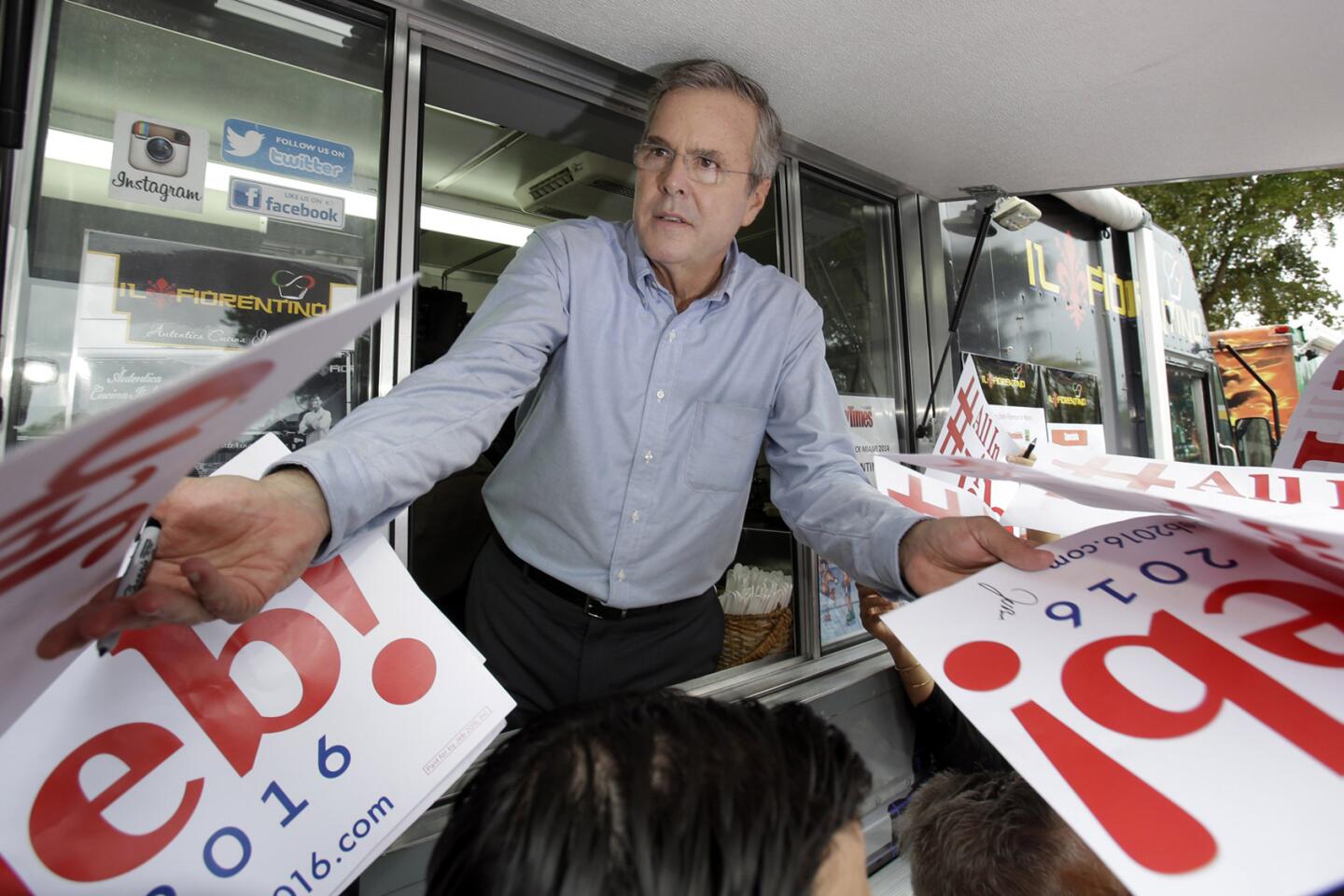

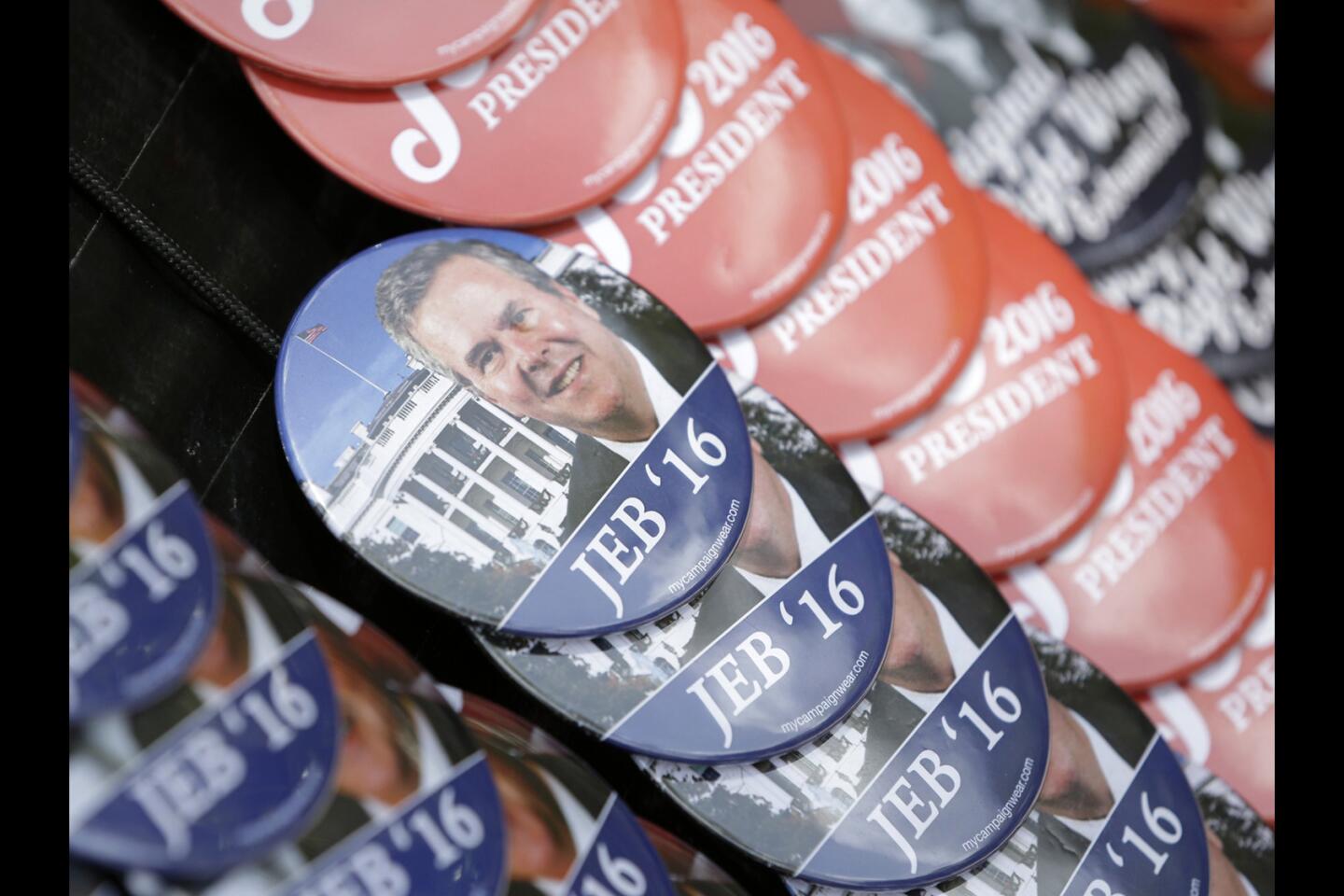

Jeb Bush enters 2016 race, signaling he’s a different kind of Republican

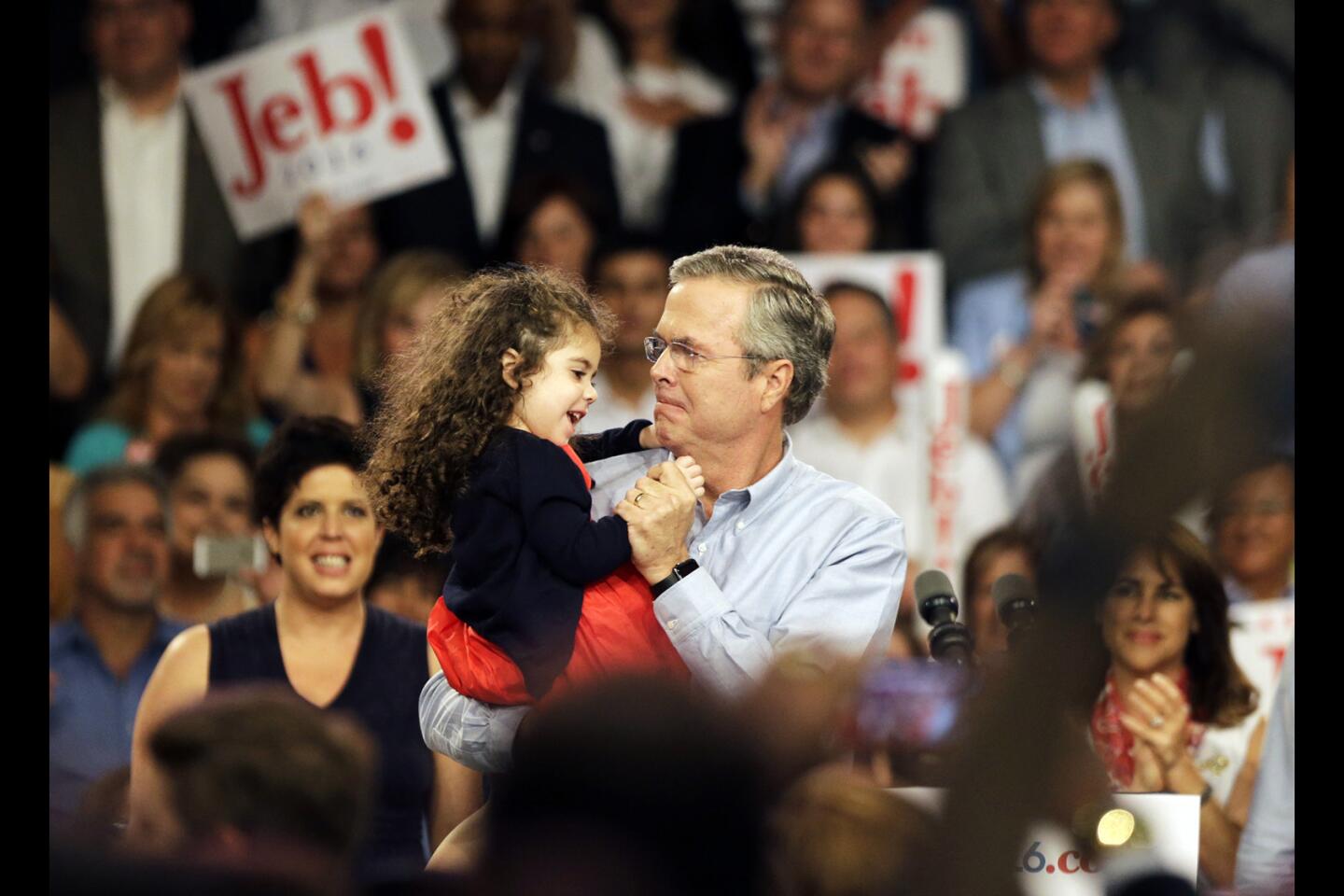

Reporting from Miami — Neither was in the audience but Jeb Bush jokingly alluded to both, drawing appreciative laughs by noting he met his first president the day he was born and the second the day he came home from the hospital.

Then Bush, formally announcing his run for the White House, turned serious, making his point humbly and unmistakably clear: The presidency, he said, was something to be earned, not inherited.

“Not a one of us deserves the job,” the former Florida governor told a hometown crowd Monday, “by right of resume, party, seniority, family or family narrative.”

“It’s nobody’s turn,” Bush went on, in what served as well as a poke at the Democratic front-runner, Hillary Rodham Clinton. “It’s everybody’s test, and it’s wide open — exactly as a contest for president should be.”

The question of dynastic succession for Bush, the son of former President George H.W. Bush and the younger brother of former President George W. Bush, is one of the largest hurdles facing him in his historic White House bid.

But beyond that, Bush’s candidacy represents a gamble. More than most others in the field, Bush has been willing to challenge party orthodoxy, chiefly in his call for a comprehensive overhaul of the nation’s immigration laws — eschewing the enforcement-driven approach favored by many in the Republican Party — and continued support for federal education standards that are anathema to many conservatives.

The bet is that Bush can begin to stake positions with appeal to a broader electorate in November 2016, especially the rapidly growing share of Latino voters, without destroying his chances of first winning his party’s nomination.

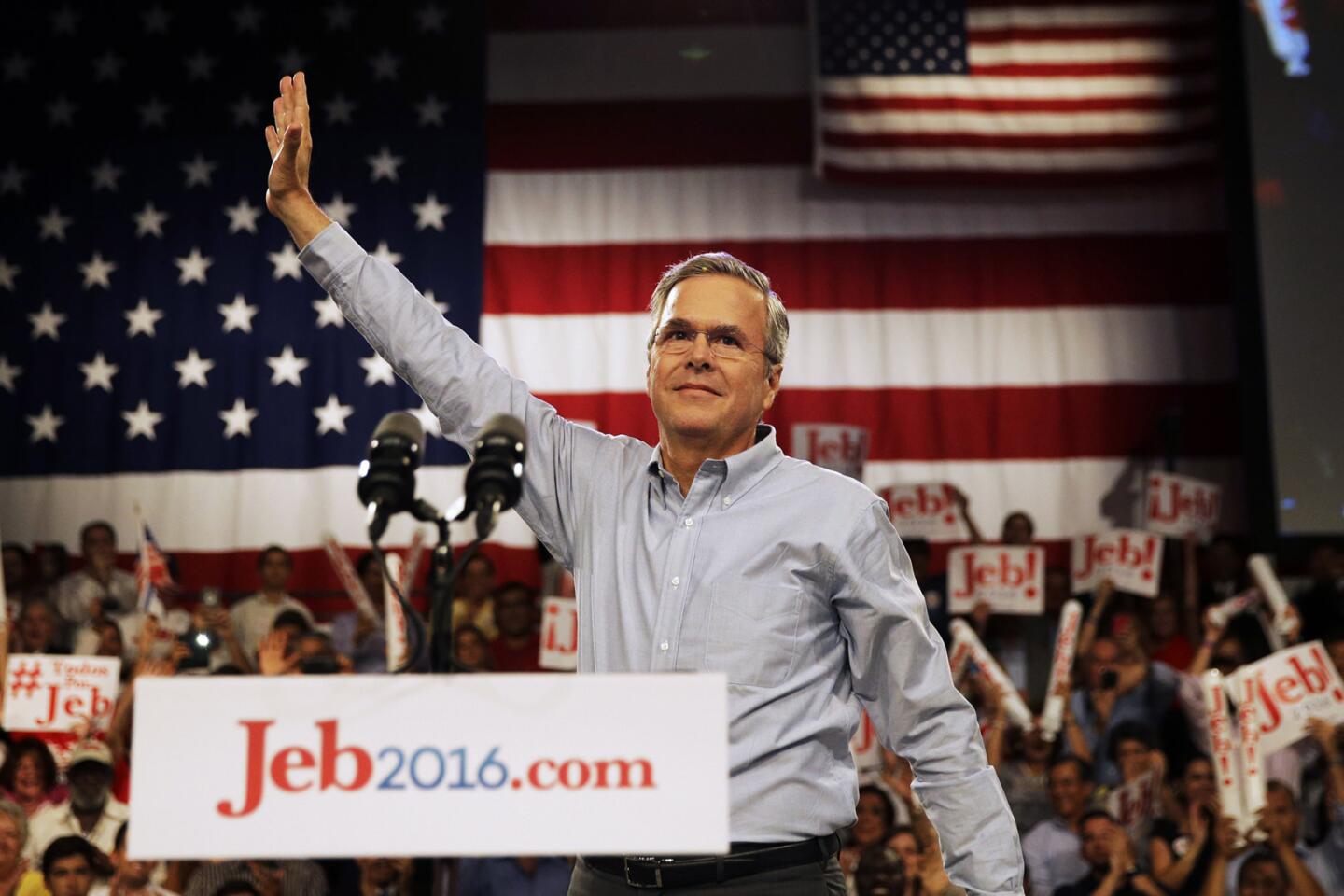

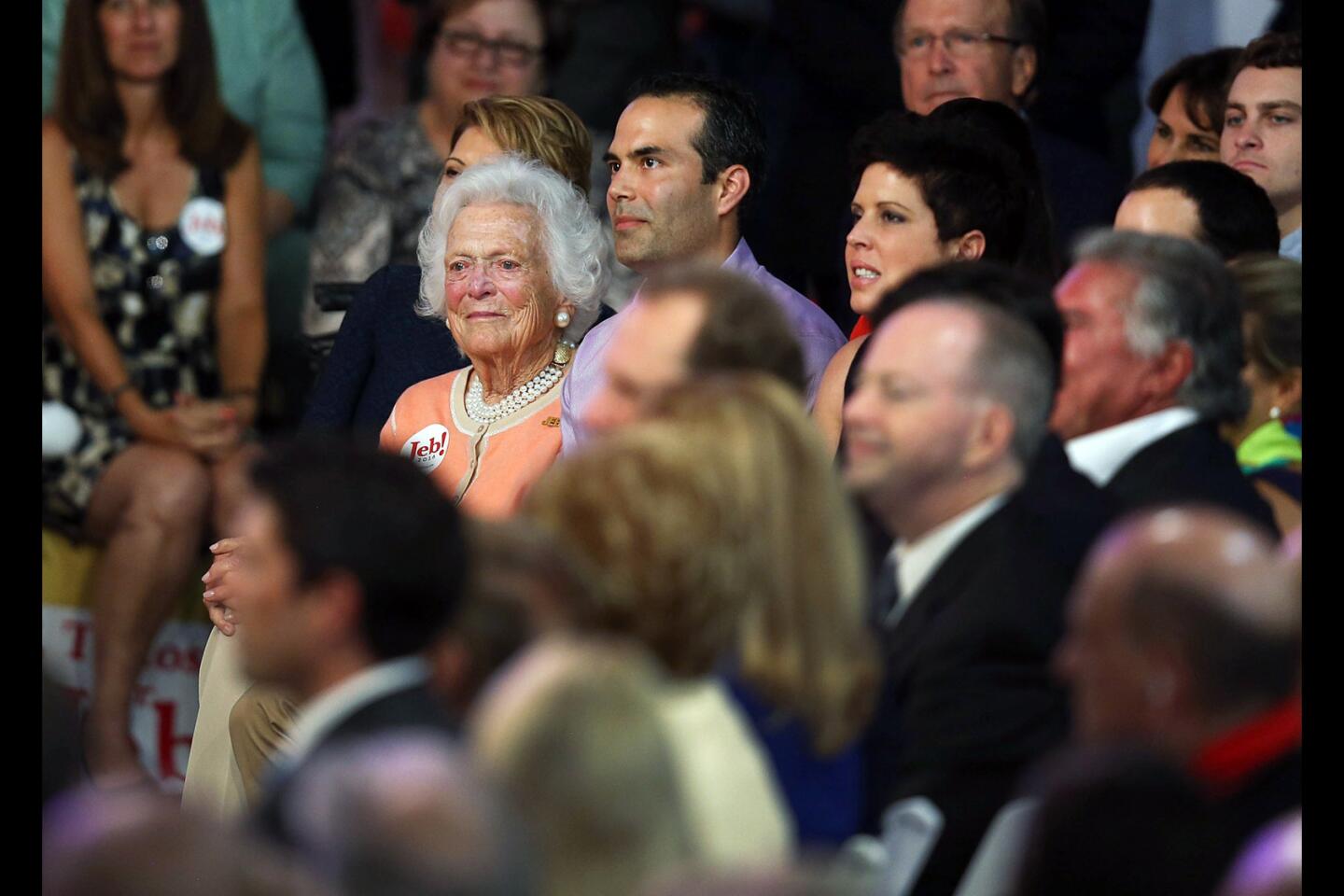

Although his official launch was a mere formality after six months of unfettered campaigning, it served as a fresh start of sorts for a candidacy that has proved less than overwhelming. The event, attended by his mother, former First Lady Barbara Bush, and his wife, children and other family members, drew hours of television coverage and dozens of reporters to swampy south Florida.

The atmospherics, as much as Bush’s message — upbeat, accomplished and distinct from dysfunctional Washington — were very much intended to signal that, even at age 62, he is poised to be a different sort of Republican.

From the Latin music pulsing outside to the mingling of Spanish and other languages inside a community college gymnasium, Bush’s rally was no typical gathering of the aging, white, rural GOP.

The chosen venue, Miami Dade College, was itself a signal, telegraphing Bush’s hope to reach beyond what has been his party’s shrinking political base. A branch of the state public university system, the palm-dotted suburban Miami campus has one of the largest enrollments of Latino students in the country.

Inside the heavily air-conditioned gym, Bush delivered the message he hopes will serve him through the long, grinding campaign, mixing can-do confidence and a highly laudatory recitation of his record as governor with subtle jabs at the several senators competing with him for the GOP nomination.

Aiming at President Obama and swatting his congressional rivals in turn, Bush suggested the record of the incumbent administration showed that “executive experience is another term for preparation, and there is no substitute for that.”

Yet for all the newness he sought to project and despite the large contingent of young people in the audience, much of Bush’s message was old-time Republican gospel, including calls for lower taxes, less regulation and more limited government. His promise to banish the special interests and “shake up the culture of Washington” is standard for candidates of both parties.

In one of Monday’s few specific pledges, Bush staked an ambitious goal of 4% annual growth for each year he is president, creating a cumulative 19 million jobs, though he did not say whether that impressive number would be created in a single term or require two.

Bush, who started in Florida politics in the early 1980s helping build the state Republican Party, had been mentioned as a presidential prospect for years. Still, he surprised many in December when he finally expressed interest in running.

Perhaps more surprising, though, has been his performance since.

Far from the commanding front-runner some anticipated — or his brother proved when he ran in 2000 — Bush has failed to break free of a large and growing field of GOP rivals, by far the biggest in recent memory. More than a dozen hopefuls have declared their candidacy or are weighing a White House bid.

Bush’s emergence did help dissuade Mitt Romney, the 2012 Republican nominee, from making a third try for president. Otherwise Bush and his formidable money-raising machine have proved considerably less than intimidating.

Ohio Gov. John Kasich, who will probably vie with Bush for the support of establishment and less ideologically conservative Republicans, has indicated he plans to enter the race by the end of summer. New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, another competitor for anti-Washington, establishment GOP support, is expected to officially announce his candidacy in coming weeks.

Even Marco Rubio, Florida’s junior senator, declined to stand aside for Bush, who helped mentor Rubio early in his political career. (The two exchanged friendly Twitter messages Monday before Bush’s rally.)

Time has not done him any favors.

The Republican Party has moved considerably to the right since Bush last ran for office more than a dozen years ago. And his political rustiness has shown, most notably when he bobbled an easily foreseen question about whether he backed the unpopular war his brother launched in Iraq. Bush finally said, given what is known today, he would not have supported the invasion.

In a sign of concern, Bush last week replaced his campaign manager, shifting him from day-to-day operations to a position focused on winning the earliest-voting states.

Change, especially in politics, is never easy.

At one point Monday, Bush was interrupted by demonstrators who stood up and revealed T-shirts spelling out “Legal status is not enough” — a reflection of unhappiness with Bush because he backed away from advocating a path to citizenship for the millions of immigrants in the country illegally.

Turning to address his critics, Bush vowed to “pass meaningful immigration reform,” though he offered no specifics.

To win the presidency, Bush suggested he would seek to bring the Republican Party to his way of thinking, not the other way around. If he succeeds, that in itself would be a historic achievement.

mark.barabak@latimes.com

Twitter: @markzbarabak

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.