Race enters the Democratic fray

ATLANTA — Jarvis Jenkins and Kytu Ivory are two black voters with two very different ideas about the racial tensions that have flared between presidential hopefuls Barack Obama and Hillary Rodham Clinton.

Jenkins, a transit system worker, was not offended by Clinton’s recent comment that “it took a president” to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 -- a remark that some critics have found disrespectful toward the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

Ivory, however, thinks that those words are part of a concerted effort by Clinton to inject race into the campaign.

But like many other African American voters here, the men could agree on one thing: In a presidential contest featuring perhaps the most viable black candidate in history, it was inevitable that race would emerge. It was just a matter of time.

“They’re always going to bring that up,” said Jenkins, 53, as he helped tourists navigate a bus station Monday in downtown Atlanta.

“We knew it was coming,” said Ivory, a 40-year-old construction worker, speaking in a food court a few blocks away.

The recent firestorm over Clinton’s words -- as well as recent comments by her supporters seen as carrying racial overtones -- has made for a tantalizing story line in recent days. It also could influence the votes of some blacks in states such as Georgia, where African Americans are a key part of the Democratic electorate and where primaries will be held on Feb. 5, Super Tuesday.

Lolly Lovett, 49, a funeral home office administrator from Savannah, has had a hard time deciding between the two candidates, but said that Clinton’s comments “were the first strike against her” and might make it “a little easier to choose.”

Clinton made her comments in an interview with Fox News last week. She was supporting her contention that pragmatic leadership skills like hers are sometimes preferable to soaring oratory like Obama’s.

“Dr. King’s dream began to be realized when President Lyndon Johnson passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964,” she said, adding: “It took a president to get it done.”

But Clinton aides have suggested that Obama’s campaign is fanning the flames. They point to an Obama staffer’s memo that compiled other potentially inflammatory statements by Clinton and her allies, including a comment by New York Atty. Gen. Andrew Cuomo that candidates can’t “shuck and jive” through press conferences in New Hampshire.

Another nerve was struck this weekend when Clinton supporter Robert L. Johnson, the founder of Black Entertainment Television, said at a campaign rally that the Clintons were working on black issues when Obama was doing the things that “he said . . . in his book” -- which was widely interpreted as a reference to Obama’s admitted drug use as a young man.

(Johnson later issued a statement that he was referring to Obama’s work as a community organizer.)

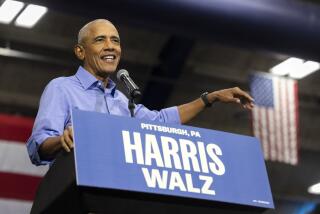

On Monday, both candidates seemed anxious to quell the feud. Obama -- who earlier called Clinton’s civil rights statement an “ill-advised remark” -- broke from regular campaign events in Reno, five days before the Nevada caucuses, to tell reporters that the disagreement should not obscure other issues.

“We’re all Democrats. We all believe in civil rights. We all believe in equal rights,” Obama said.

In a prepared statement, Clinton said the parties should seek “common ground.”

“Over this past week, there has been a lot of discussion and back-and-forth -- much of which I know does not reflect what is in our hearts,” she said.

A number of black voters said Monday that they had not paid much attention to the spat, perhaps lending some perspective to pundits, journalists and bloggers who have spent the last few days decoding alleged code words and analyzing charges of tactical jujitsu by the two campaigns.

Undecided voter Valerie Dickie, 36, of Lithonia, Ga., said that as far as racial controversies go, this one seemed trivial.

“Let’s get to the issues,” Dickie said. “How are we going to help people from losing their homes to foreclosures? How are we going to get our troops home? How are we going to improve our education system?”

But Ernest McDowell, 50, a truck driver from Lithonia and an Obama supporter, was hurt by Clinton’s comment.

“Clinton blew it,” he said. “It was bad wording and bad timing.”

McDowell disputed the New York senator’s version of history, arguing that it was pressure from those outside the political system who forced Johnson to take action. At that juncture in the 1960s, he said, “people were getting impatient.”

James Arnold, 43, an Atlanta shoe shiner, didn’t doubt the veracity of Clinton’s statement. King’s platform, he said, “wasn’t worth a hill of beans unless somebody passed it.”

But Arnold figured that the words were calculated to bait Obama into speaking more about his race, thus distancing white voters.

“That’s what it is,” he said. “She’s trying to pick him clean.”

Experts, too, are trying to gauge how calculated the Clinton rhetoric is. David Bositis, a fellow at the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies -- a think tank that focuses on issues of concern to blacks -- thinks the Clinton camp is sending signals that could alienate blacks but enhance the candidate’s appeal to working-class whites.

“Hillary’s people would like Obama to be seen as the black candidate,” he said. “That would help in terms of her appeal to white working-class voters. They are voters who represent a backbone of the campaign.”

Bositis, who is not affiliated with either campaign, said it reminded him of moves Bill Clinton made in his 1992 campaign that sent a message that “he was not going to be pushed around by Jesse Jackson.”

Bositis also mentioned Clinton’s high-profile 1992 return to Arkansas for the execution of Ricky Ray Rector, an African American, and to Clinton’s rebuke of black hip-hop artist Sister Souljah.

Despite those moves, the Clintons have famously retained deep reserves of goodwill among black voters, and a number of them Monday said they were willing to give Hillary Clinton the benefit of the doubt.

Henry Burton, 59, of Atlanta said he knew her words were coming from a trusted friend to the black community.

“I didn’t see anything wrong with that at all,” he said.

But Joseph Arrington II, an Atlanta lawyer and Obama supporter, said that if the Clintons’ motives were pure, it would be difficult to convince a public that has been told, over and over, of their penchant for political genius.

“Even if it isn’t a well-conceived effort on their part,” he said, “it’s going to be perceived that way.”

Fausset reported from Atlanta and Hook from Washington.

Times staff writers Jenny Jarvie, Peter Nicholas, James Rainey and Stuart Silverstein contributed to this story.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.