In Trayvon Martin case, a complex portrait of shooter emerges

SANFORD, Fla. — For many Americans, George Zimmerman has become the face of barbarous vigilante justice.

For Olivia Bertalan, he was the face of compassion: a neighbor of consummate graciousness and low-key gallantry.

About six months before Zimmerman shot and killed an unarmed black teenager in his town house complex, he was standing in Bertalan’s doorway, asking what he could do to help her.

A group of young men had just broken into Bertalan’s town house as she and her infant cowered in a locked bedroom. The intruders took a $600 camera and a laptop. After police had come and gone, the doorbell rang, and there was Zimmerman: 5 feet 9, in a shirt and tie, his body a little doughy, his demeanor gentle.

He introduced himself and gave her phone numbers at which she could call him anytime. He gave her a heavy-duty lock to bolster the sliding-glass door that the men had forced open. He told her she could stay with his wife down the street if she ever felt scared again.

“That first impression was really sweet,” Bertalan, 21, said this week. “It really does break my heart how they’re portraying him as a coldblooded murderer.”

This is the impression of Zimmerman shared by a number of neighbors and acquaintances, one that only compounds the complexity and tragedy in the case of Trayvon Martin, whom Zimmerman gunned down Feb. 26 in a suburban side yard.

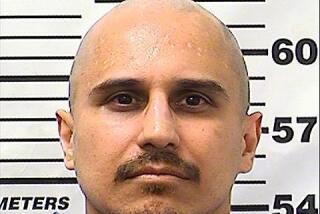

Zimmerman, who claimed self-defense, has not been arrested, and outraged observers have impugned the 28-year-old neighborhood watch captain, and the justice system, as racist. Friends and family have said that Zimmerman, who is half-Peruvian, has black friends and even family members, and was not motivated by prejudice.

A portrait is emerging of a man whose life, though pocked with allegations of aggressive behavior, was also marked by the kind of neighborhood-level engagement — he helped plan block parties — that social scientists have argued are key to combating the atomization and alienation of suburban life.

One crucial and unresolved question, however, is whether Zimmerman, who made more than 40 complaint calls to local police since 2004, finally took his engagement a step too far on a rainy Sunday night in February.

Zimmerman grew up in suburban Manassas, Va. His father, he has said, was a magistrate judge, his mother a deputy court clerk.

A decade ago he moved to Lake Mary, Fla., just north of Orlando, and into a home his parents purchased in Huntington Ridge, a subdivision of handsome, though not ostentatious, houses.

The teenager enrolled in Seminole State College of Florida, where, according to the school, he received an insurance agent’s certificate in 2003. He impressed some as mature for his age, planning a Fourth of July celebration with the head of the homeowners association.

“I don’t think he’d ever intentionally hurt anybody,” said a neighbor who asked not to be identified because she received a threatening phone call directed at the Zimmermans.

But there had been trouble. In 2008, in correspondence to the local sheriff’s department, Zimmerman said he was involved three years earlier in an “altercation with an undercover officer that was taking part in a … sting for underage drinking” near a university. He was charged with battery of an officer and resisting an officer with violence. Court records show the charges were reduced to a misdemeanor of resisting an officer without violence. A judge ordered him to a pretrial diversion program.

Court records also show that a woman filed a petition for an injunction against Zimmerman that same year, citing domestic violence. According to the Miami Herald, the woman, who was his ex-fiancee, said they fought and engaged in a pushing match. Zimmerman also filed a petition, and a judge ordered the couple to keep away from each other for a year.

By this point, he had already begun repeatedly calling police — to report potholes, aggressive drivers, neighbors who left their garage doors open.

In June 2007, he reported two Latino men and a white man with a “slim jim,” a device used to jimmy open a locked car. Police determined the men were locked out of their car.

In April 2011, after he had moved to his most recent residence in Sanford, he called to report an African American boy, about 7 years old, walking down a busy street. The report states that Zimmerman was concerned for the boy’s well-being.

Zimmerman reportedly worked in the insurance industry, but he was also deeply curious about law enforcement. In 2009, he completed a 14-week course by the Seminole County Sheriff’s Office called the Community Law Enforcement Academy.

Meanwhile, Zimmerman’s neighborhood, the Retreat at Twin Lakes, was proving not to be much of a retreat at all. Olivia Bertalan’s ordeal was just one of a rash of break-ins in the area: Police records show at least seven burglaries from July through February.

The police told the Bertalans to get a gun and a big dog. They passed that advice along to Zimmerman, who, she said, got a Rottweiler. It is unclear when he received his permit to carry a concealed weapon; the Florida agency that grants such permits cannot, by statute, reveal such details.

Neighborhood watch efforts were doubled and Zimmerman spearheaded the initiative. Some of the suspects were young black men, but Bertalan said he never uttered a racist word.

The Bertalans, sick of the crime, moved out Feb. 15. Eleven days later, Zimmerman was headed to a grocery store when he spotted Trayvon Martin walking in the neighborhood in a dark hoodie. He called 911.

Since August, he had called four other times to report what he considered to be suspicious black males in the neighborhood.

“This guy looks like he’s up to no good or he’s on drugs or something,” he said.

He told the operator that the teen was coming to check him out: “He’s got something in his hands. I don’t know what his deal is.”

A moment later, he said, “These ass— always get away,” and reported that the young man was running.

The operator asked whether Zimmerman was following Martin. Yes, he said. The operator told him not to do so.

A lawyer for Martin’s family would later assert that the boy was on the phone with his girlfriend. Martin told her a man was following him. She suggested he run.

What happened next is unclear. The Martin family attorney says the girlfriend heard Martin say, “Why are you following me?” and a man’s voice reply, “What are you doing around here?”

Police concluded that Zimmerman lost sight of Martin and was walking to his SUV when the youth appeared in his path, confronting him and punching him.

Numerous 911 calls reported two men scuffling. In a recording, an anguished male voice cries out in the background repeatedly. Then there is a single sound, sharper than a hand clap.

Sanford Police Officer Timothy Smith rushed to the scene, describing it later in his report.

Zimmerman told the officer he had shot Martin, and was still armed.

Smith cuffed him and removed a black Kel-Tec 9-millimeter semiautomatic handgun from his waistband.

He noticed that Zimmerman had a bloody nose and blood on the back of his head. Zimmerman was placed in the back of a squad car.

“I was yelling for someone to help me,” the officer overheard Zimmerman say, “but no one would help me.”

Times staff writer Michael Muskal in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.