The 1% aren’t like the rest of us

Over the last two years, President Obama and Congress have put the country on track to reduce projected federal budget deficits by nearly $4 trillion. Yet when that process began, in early 2011, only about 12% of Americans in Gallup polls cited federal debt as the nation’s most important problem. Two to three times as many cited unemployment and jobs as the biggest challenge facing the country.

So why did policymakers focus so intently on the deficit issue? One reason may be that the small minority that saw the deficit as the nation’s priority had more clout than the majority that didn’t.

We recently conducted a survey of top wealth-holders (with an average net worth of $14 million) in the Chicago area, one of the first studies to systematically examine the political attitudes of wealthy Americans. Our research found that the biggest concern of this top 1% of wealth-holders was curbing budget deficits and government spending. When surveyed, they ranked those things as priorities three times as often as they did unemployment — and far more often than any other issue.

If the concerns of the wealthy carry special weight in government — as an increasing body of social scientific evidence suggests — such extreme differences between their views and those of other Americans could significantly skew policy away from what a majority of the country would prefer. Our Survey of Economically Successful Americans was an attempt to begin to shed light on both the viewpoints and the political reach of the very wealthy.

While we had no way to measure directly the political influence of those surveyed, they did report themselves to be highly active politically.

Two-thirds of the respondents had contributed money (averaging $4,633) in the most recent presidential election, and fully one-fifth of them “bundled” contributions from others. About half recently initiated contact with a U.S. senator or representative, and nearly half (44%) of those contacts concerned matters of relatively narrow economic self-interest rather than broader national concerns. This kind of access to elected officials suggests an outsized influence in Washington.

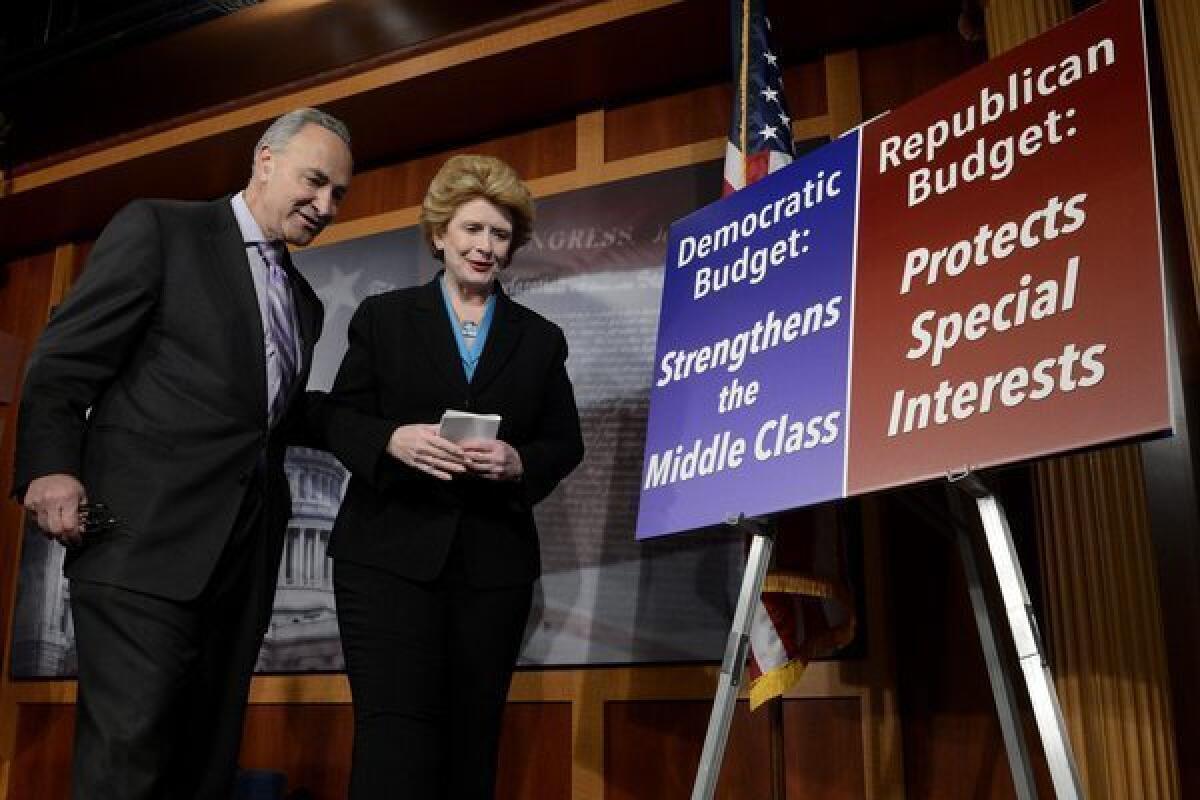

On policy, it wasn’t just their ranking of budget deficits as the biggest concern that put wealthy respondents out of step with other Americans. They were also much less likely to favor raising taxes on high-income people, instead advocating that entitlement programs like Social Security and healthcare be cut to balance the budget. Large majorities of ordinary Americans oppose any substantial cuts to those programs.

While the wealthy favored more government spending on infrastructure, scientific research and aid to education, they leaned toward cutting nearly everything else. Even with education, they opposed things that most Americans favor, including spending to ensure that all children have access to good-quality public schools, expanding government programs to ensure that everyone who wants to go to college can do so, and investing more in worker retraining and education.

The wealthy opposed — while most Americans favor — instituting a system of national health insurance, raising the minimum wage to above poverty levels, increasing the Earned Income Tax Credit and providing a “decent standard of living” for the unemployed. They were also against the federal government helping with or providing jobs for those who cannot find private employment.

Unlike most Americans, wealthy respondents opposed increased regulation of large corporations and raising the “cap” that exempts income above $113,700 from the FICA payroll tax. And unlike most Americans, they oppose relying heavily on corporate taxes to raise revenue and oppose taxing the rich to redistribute wealth.

Some of the differences between the political views of the wealthy and other Americans may be explained by differences in the two groups’ economic experiences and self-interest. The wealthy are likely to have better information about the costs of government programs (for which they pay a lot of taxes) than about the benefits of those programs. They don’t usually have to rely on Social Security, for example, let alone food stamps or unemployment insurance.

Another possibility is that the wealthy — who tend to be highly educated, well informed and committed to charitable giving — seek the common good as they see it, and in fact know better than average Americans what sorts of policies would benefit us all. On the issue of federal deficits, for example, the public has come to see government debt as an increasingly important problem over the last two years, reducing the gulf between their views and those of the wealthy. Is that because the wealthy were ahead of the curve, or because their concern helped stimulate a steady drumbeat of deficit alarmism in the media and in Washington?

Our pilot study included a relatively small number of wealthy citizens, and they were all from a single metropolitan area. A larger-scale national study is needed to pin down more precisely the views of wealthy Americans about public policy. We need to understand how they formed the preferences they have, and how wealthy people from different regions, industries, and social backgrounds differ in their political views and behavior. We also need to understand more about their political clout.

Our initial results suggest the wealthy have very different ideas than other Americans on a variety of policy issues. If their influence is far greater than that of ordinary people, what does that mean for American democracy?

Benjamin I. Page is a political science professor at Northwestern University and co-author of “Class War? What Americans Really Think About Economic Inequality.” Larry M. Bartels is a political science professor at Vanderbilt University and author of “Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.