Yes on Proposition 30, no on Proposition 38

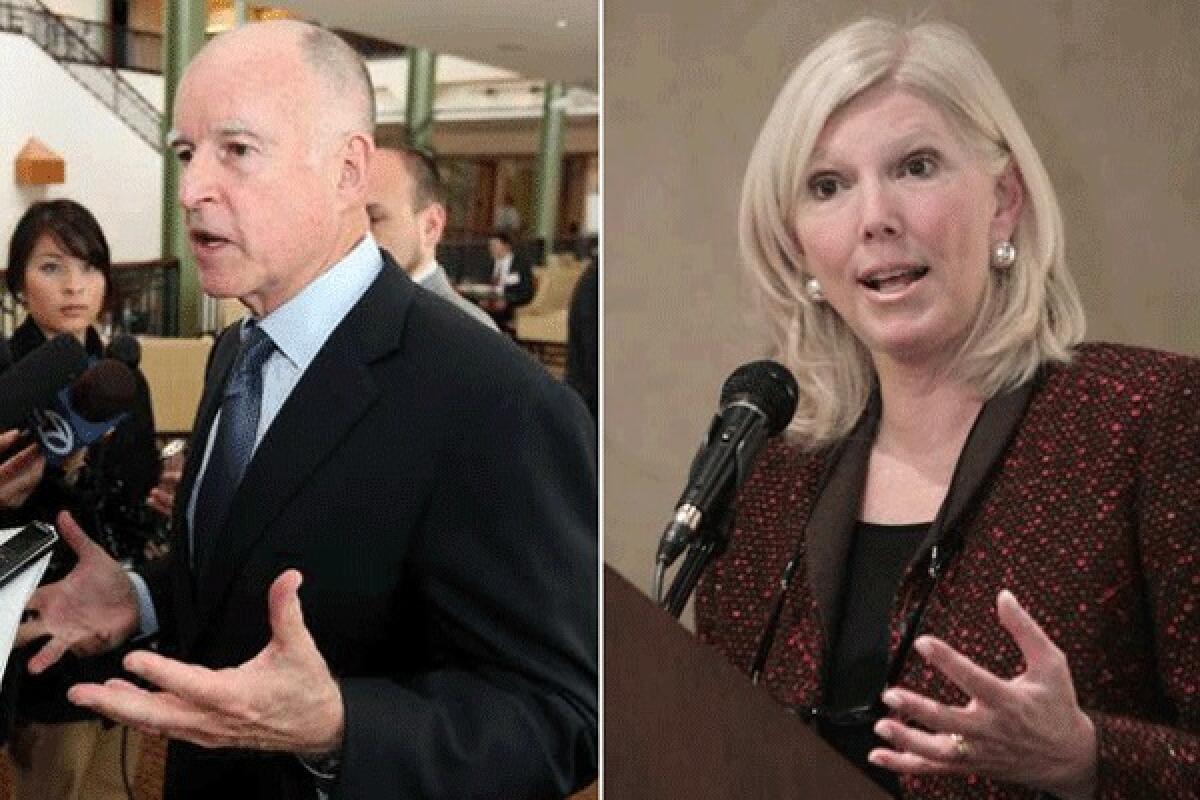

The day Gov. Jerry Brown took office in 2011, the state budget was more than $25 billion in the red — the latest installment in a long-running drama of boom-and-bust budgeting. Since then, lawmakers have slashed billions of dollars from education, health, public safety and community development programs, reducing the general fund to the smallest share of the economy in 40 years. Barring a miraculously speedy turnaround in the economy, however, the budget will remain far out of balance for the next several years unless Sacramento raises revenue or cuts spending by a draconian $6 billion annually. Proposition 30, Brown’s proposal for a temporary increase in income and sales taxes, would fill that hole. Proposition 38, a proposed income tax hike backed by civil rights attorney Molly Munger and the California PTA, would not. The Times urges a yes vote on Proposition 30.

California voters have been resolute when it comes to ballot measures that raise taxes. Over the last decade, they’ve defeated 10 and approved just one, a 1% surtax on incomes above $1 million to support mental health programs. The failed measures include levies on cigarettes, vehicle licenses, oil companies, phone calls and taxpayers with incomes over $400,000. It made little difference to voters whether the dollars were slated for the general fund or a specific and popular purpose, such as keeping state parks open or investing in cancer research.

For years, lawmakers papered over the revenue shortfalls with accounting gimmicks and one-time measures, building up what Brown has called a $35-billion “wall of debt.” To their credit, Brown and top legislative Democrats have ratcheted back on those techniques in favor of real cost-saving changes in state programs. In the process, they’ve made painful cuts with damaging long-term consequences, effectively putting the lie to the argument that the state can solve its fiscal problems just by spending less.

ENDORSEMENTS: The Times’ recommendations for Nov. 6

Two years of belt-tightening have left parts of the state safety net in tatters and pushed college costs out of the reach of many families. Cuts in aid to the poor and working poor in this year’s budget eliminated child-care subsidies for 14,000 children and preschool slots for 12,500 children. State aid for low-income seniors and the disabled is now as low as it was in 1983; welfare checks are smaller than they were 25 years ago. And K-12 spending per pupil remains $1,000 less than it was five years ago. California now spends less per student than all but three states.

The picture would only worsen if Proposition 30 is defeated, leaving a nearly $6-billion gap in the budget. If that were to happen, state law calls for $4.8 billion in automatic “trigger cuts” to public schools, more than $1 billion in cuts to higher education budgets and $100 million in assorted other reductions. K-12 schools would be authorized to cancel up to three weeks’ worth of classes in 2012-13 and 2013-14, and per-pupil spending would drop about $700. Fire safety would take a substantial reduction; overburdened courts would be burdened still further, meaning less access to justice for people of all socioeconomic backgrounds. Cuts of this magnitude are unacceptable.

Most of the money raised by Proposition 30 would come from increasing the tax rate on incomes above $250,000 per individual (or $500,000 per couple) by 1 to 3 percentage points for seven years. The rest — about $1.2 billion a year — would come from increasing the state sales tax by a quarter of a cent for four years.

The measure requires that 89% of the money raised goes to K-12 schools and 11% to community colleges, but those dollars would help satisfy the minimum annual funding requirements of Proposition 98 (the 1998 ballot measure that requires about half the general fund to be spent on public education). The result would be about a $3-billion increase in annual spending on schools and about $3 billion freed up in the general fund for other state priorities. The proposition would also make a critically important change in the state Constitution, dedicating state revenue (mainly from sales taxes) to local governments to fund the criminal justice programs and other responsibilities Sacramento transferred to them under Brown’s “realignment” initiative.

Critics argue that a tax increase is ill-timed, considering the fragile economy. It would make the state, whose income taxes are already among the highest in the nation, even less competitive, increasing the exodus of businesses and individuals. They also argue that the state’s budget troubles stem from out-of-control spending, not a shortage of revenue. Even without Brown’s tax increase, the state budget is expected to be larger in fiscal 2012-13 than the year before. Once the state starts selling bonds for high-speed rail, the total will go even higher.

Such criticism ignores the realities of inflation, population growth and economic expansion over the years, all of which put pressure on the budget. Even including the $40 billion collected in special state funds for everything from victims’ restitution to wildlife preservation, the state budget this year amounts to less per resident than in 2010, 2000 or 1990, and will account for a smaller share of the economy than practically any year in the last three decades.

Sacramento can and should do a better job managing its money. And voters can certainly question the wisdom of building a high-speed rail line when the state’s once-peerless education system is struggling (although they shouldn’t forget that they green-lighted the project). But the rail project is a weak argument against Proposition 30; even if the initial bonds are sold in the coming year, their cost is expected to be a small fraction of the budget gap that would result if Proposition 30 were defeated.

Proposition 38, by contrast, is more focused on pumping money into schools to reduce class sizes, restore instruction in the arts and other subjects that have been lost to budget cuts, improve classroom technology and update teaching materials. The measure would raise an estimated $6 billion to $8.5 billion annually for public K-12 schools for 12 years. That’s the equivalent of $1,000 to $1,400 per student. It also would raise $1 billion or more annually for early childhood education, including a new Early Head Start program for children under age 3 from low-income families.

The source of the money would be a temporary increase in personal income taxes. Proposition 38 would raise rates on a sliding scale, affecting taxable incomes as low as $7,316 a year. The vast majority of the money raised, though, would come from the top 5% of the state’s earners — those making more than $200,000 — whose rates would increase from 1.8 to 2.2 percentage points.

The measure is akin to a no-confidence vote for Sacramento; the money it would raise for schools would flow directly to local school boards and charter school governing bodies, bypassing the Legislature and state education officials. It would help relieve the state’s budget problems, but only for four years. From mid-2013 to mid-2017, 30% of the money from Proposition 38 would be dedicated to paying down school bonds and other state debt, freeing about $3 billion in the state’s general fund for other purposes.

Munger’s proposal includes several provisions restricting how schools could spend the new money. For example, none of it could be used to increase salaries. But the restraints appear to deter some kinds of reform, such as lengthening school days or years, creating regional pools of resources or offering more instruction online. And the measure bars the Legislature from changing any provisions that prove problematic; instead, any amendments would have to be made by the voters.

The biggest shortcoming of Proposition 38, though, is what its supporters consider its main selling point: the fact that it walls off from the general fund most of the money it raises. That’s a real problem for the current fiscal year, which will be over before much of the funding would kick in.

It is not possible for both propositions to become law. If Proposition 38 attracts a larger majority than Proposition 30, none of the provisions of Proposition 30 will take effect, and vice versa. As a consequence, if Proposition 38 comes out on top, the nearly $6 billion in trigger cuts to schools and other programs would go into effect unless the Legislature scrambled to change the law. These cuts could leave some non-school programs too far behind to ever catch up.

Proposition 38 is a well-intentioned attempt to aid California’s beleaguered schools, but a vote for the measure is a potential vote against Proposition 30. In addition, the singular focus of Proposition 38 on education is misplaced, particularly in light of the deep and damaging cuts the state has been making in programs that aren’t already guaranteed half the state’s general fund. As much as the schools need help, they aren’t the only ones in need of rescue. And walling off another chunk of the state’s revenues would only make it harder for lawmakers to address the breadth of the state’s needs. The Times urges a yes vote on Proposition 30, and a no vote on Proposition 38.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.