Kenneth Starr: Open to the public

This is the seventh in an occasional series of conversations with Southern California activists and intellectuals. The series and videotaped interviews with the subjects are collected at latimes.com/news/opinion/ lavisions.

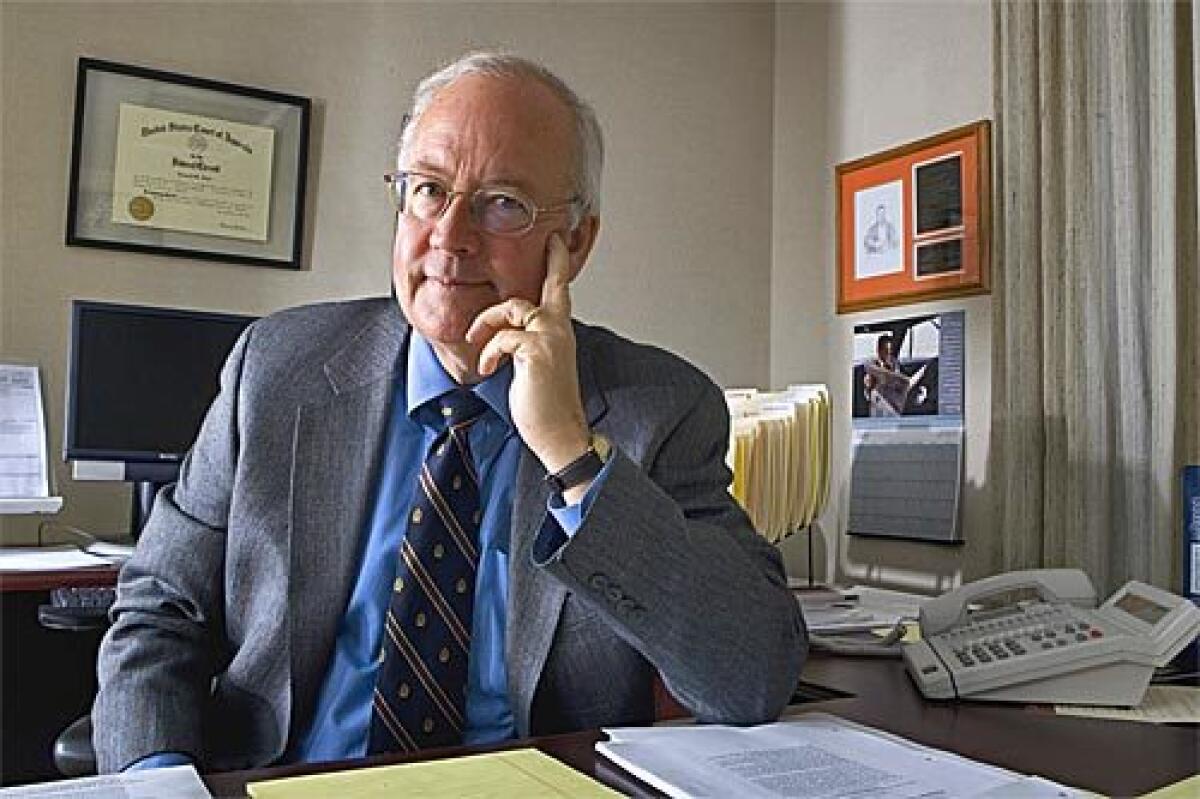

To meet Kenneth Starr is to question the anger of his most partisan critics and the ardor of his most ideological admirers.

As few have forgotten, Starr’s pursuit of President Clinton endeared him to Clinton’s enemies but also made him, for some, a modern Inspector Javert, sneeringly derided in one publication as a “pious lawman.” His report on the Clinton-Lewinsky matter is a relic of that era; its descriptions of sex in the Oval Office were so graphic that it came with a warning for children to stay away, a first in the annals of such investigations.

And yet, here Starr is, atop the law school at Pepperdine University, cheerfully imagining a culture of engaged and conscientious young lawyers, wistfully harking to a time when the nation was less divided and acrimonious.

His critics might be surprised, but Starr is neither monster nor prude. He is genial, reflective and easygoing, lighthearted even. Committed to public service, he speaks most eloquently on the notions of service and compassion. One is reminded that he is, after all, a man passed over for the Supreme Court because he was believed to be too liberal by some conservatives. Starr is, in short, much of what liberals love, notwithstanding that he was responsible for the impeachment of a president many of them so dearly miss.

A conversation with Starr in his Pepperdine office is framed by his interests. Law papers and journals are scattered around the room; outside a window behind his desk lies the Pacific Ocean. He speaks glowingly of California and brushes aside any suggestion that Los Angeles -- with its liberal billionaires, politicians, lawyers and movie stars -- is in any way an uncomfortable home for such a noted Republican.

“I’ve not been mistreated a single time,” he says. “People have been very gracious.”

Throughout the conversation, Starr takes pains to emphasize his connection to this place. He praises the area’s leading figures, those of the left and those not so left, among them former Mayor James K. Hahn, a Pepperdine alum who teaches at the school, and Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, who beat Hahn in 2005. Starr is similarly gracious toward Eli Broad and Warren Christopher, leading and longtime figures in Los Angeles’ Democratic political and cultural establishment. Starr admires Broad’s commitment to education and Christopher’s devotion to public service.

Starr worked in Los Angeles early in his career, and his law practice brought him back here frequently over the years. He came to know many of the city’s legal luminaries and happily offers up his appreciation for them too. Starr once, for instance, served as co-counsel in a case with Johnnie L. Cochran Jr. “Talk about a great lawyer,” Starr says with evident admiration.

For Starr, partisan politics has not exactly disappeared, but it has palpably receded. He speaks now of service and community, of engaging students in the affairs of their communities and of the world. He once considered running for the U.S. Senate in Virginia. Today, he describes himself as “an encourager and a facilitator,” referring to that role as “perhaps my calling.”

“We’re preparing individuals for lives of purpose, service and leadership,” he says. “Part of my goal and vision is that we want to help develop and train very able and honorable lawyers of absolute integrity, but we also want community leaders.”

Whatever one thinks of Starr’s politics or his pursuit of Clinton, his long record as a public lawyer unmistakably suggests an advocate who has chosen service over money. Starr was a clerk for Chief Justice Warren Burger in the mid-1970s, then practiced law privately before being named to the federal appellate bench in 1983. He reluctantly left the bench to take the post of solicitor general in 1989 -- so conflicted was he about giving up his judicial seat that Starr recalls retiring to a small room and crying after accepting the new post. He was seriously considered for the Supreme Court when Justice William Brennan retired in 1990, but Starr’s nomination was scotched by conservatives who feared he might be too liberal. (It is one of the Supreme Court’s juicy ironies that President George H.W. Bush instead picked David Souter, who went on to bitterly disappoint many conservatives because he regularly sides with the court’s liberals.)

After Starr completed his work in the Clinton investigation, he came west, where he and Pepperdine set out to build a law school that fuses faith and service with the law, part of Pepperdine’s deliberate attempt to infuse its academic excellence with religious purpose. They are at work even as Erwin Chemerinsky, newly appointed dean of UC Irvine’s law school, is building his faculty along his lines, presumably more liberal than Starr’s. The result is an impressive regional bracketing of legal intelligentsia -- with Malibu oddly on the right to Irvine’s left.

Starr pauses before responding to most questions. But on some, his replies come rapid-fire. Asked whether this city, with its relatively monolithic liberal politics, is in danger of succumbing to ideological “group think,” he does not hesitate: “Yes.”

“Is there enough debate back and forth across ideological lines in L.A.?” he’s then asked.

Again, the snap response: “No.”

“This is a city where conversation should be easy because people tend to be open and welcoming,” he then elaborates, after some prodding. “There’s a graciousness in discourse.”

For a moment, Starr seems to contemplate a tougher critique of what’s missing, but then he veers back to what pleases him.

“I’m very encouraged when I see the American spirit of what works rise above ideological rigidity. When you see great community leaders like Eli Broad saying, ‘I care about education. I’m not trying to make an ideological statement, but I’m going to be helping charter schools. ...’ People of genuine goodwill are crossing party lines. When you have an Eli Broad working closely with a Dick Riordan for the welfare of schools, that’s ... finding common ground and common cause on the great issues.”

Starr’s attention also seizes on the special obligations of lawyers, an area in which he worries that changing expectations have lessened the grandeur of the law and those who practice it. He cites the work of Anthony Kronman, a Yale law professor whose book, “The Lost Lawyer,” deplores the withdrawal of lawyers from the public sphere. Speaking to a group of law clerks earlier this year, Starr mentioned the book and implored them to follow their consciences into service. “You’re developing the habits and manners of public service,” he recalls telling them.

Here again, Starr’s answers come quickly. Asked whether lawyers today feel the same obligation to society that lawyers of his generation did, he interrupts with a brusque “No.” Why? “The profound commercialization of the law and the baleful emphasis on the bottom line,” he responds. The guiding principle of many of today’s lawyers? “Let’s make as much as the investment bankers or at least go down trying.”

So, this is Los Angeles’ Kenneth Starr -- not the pursuer of a president but rather the educator and public servant, the lawyer guided by faith, leading from a hilltop in Malibu. And yet he struggles to shed his polarizing past, trying his best to claim an old mantle of centrism despite those who still are angry at him.

“Others will come to their own views,” he says evenly. “I’ve really lived my life in the law. ... I tend to be more American and less European. Europeans are highly politicized. If you’re Tory, you read this newspaper; if you are a liberal, you read this; if you’re in the Labor Party, you read that. I like our side of the Atlantic. We try to find unity. You see that even today, even in polarized and divided America.”

Jim Newton is editor of The Times editorial pages.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.