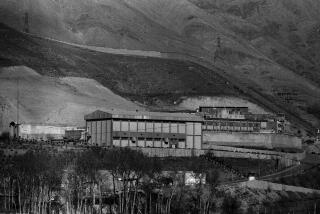

The talks in Tehran

IRAN HAS INVITED TOP Iraqi and Syrian leaders to Tehran this weekend, but there are no Americans on the guest list. The omission is hardly a snub -- U.S. diplomats probably wouldn’t have much fun there anyway -- but the talks underline the absurdity of the White House position, which is essentially to wait for a bipartisan commission to give it permission to sit down with some friends and enemies. Regional discussions about the future of Iraq are already happening. The U.S. should send out some invitations of its own.

In some respects, this weekend’s talks about ways of curbing the violence in Iraq are unremarkable. Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri Maliki visited Tehran in September, and the Syrians are frequent callers. The impending reestablishment of diplomatic relations between Iraq and Syria after a quarter of a century cements a growing bond.

The U.S. has reacted to the meeting with a kind of skeptical nonchalance (or vice versa). This reaction is understandable, but the overriding fact is that the situation in Iraq is untenable -- to the U.S., its allies and its enemies.

Under such circumstances, it makes no sense to wait until January for former Secretary of State James A. Baker III to suggest that the U.S. open talks with Iran and Syria. Nor is it smart to commission national security advisor Stephen J. Hadley to write an alternative report that appears likely to be based on the self-justifying views of the very administration insiders who are responsible for the situation in Iraq.

The U.S., supporting the Maliki government, may or may not be able to broker a peace settlement between the warring Sunni and Shiite factions in Iraq. But it has a duty to the Iraqi people to keep the neighbors from rushing in to carve up their country.

U.S. officials say that Zalmay Khalilzad, the U.S. ambassador to Iraq, is authorized to talk to Iran, but only on the topic of ending violence in Iraq. They also say that Iran and Syria should show their concern for Iraq not through rhetoric but with action -- such as cutting off their support for Iraqi militias and preventing terrorists from crossing their borders.

This is all true enough. But it also ignores the U.S.’ responsibility for Iraq. One of the administration’s goals in the war was to recalibrate the balance of power in the Middle East. In this it has succeeded spectacularly -- but the new order may be even less to its liking.

President Bush need not wait for the release of a commission report to convene a conference and invite all of the key players in Iraq’s future: Iraq, Iran, Syria, Turkey, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, as well as representatives of the Gulf Coordination Council, the European Union and the U.N. Agreeing on a mutual duty to respect and uphold Iraq’s territorial integrity would be the first goal.

If the United States fails to act, diplomacy delayed may become diplomacy derailed.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.