India’s Supreme Court delays hanging of 4 ‘Robin Hood’ gang members

NEW DELHI -- India’s Supreme Court issued a stay of execution Wednesday, delaying for at least six weeks the hanging of four members of a notorious gang, after defense attorneys argued that a nine-year delay in hearing their clemency appeal is inhumane.

The decision awaits the verdict from a similar case in which delay arguments are being heard. India’s justice system is notoriously slow, and counsel for the gang members maintains that their sentences should be commuted to life imprisonment given their long wait for a hearing.

The men have been on death row since 2004, the same year their infamous leader, Koose Muniswamy Veerappan, was killed by police in an ambush code-named Operation Cocoon.

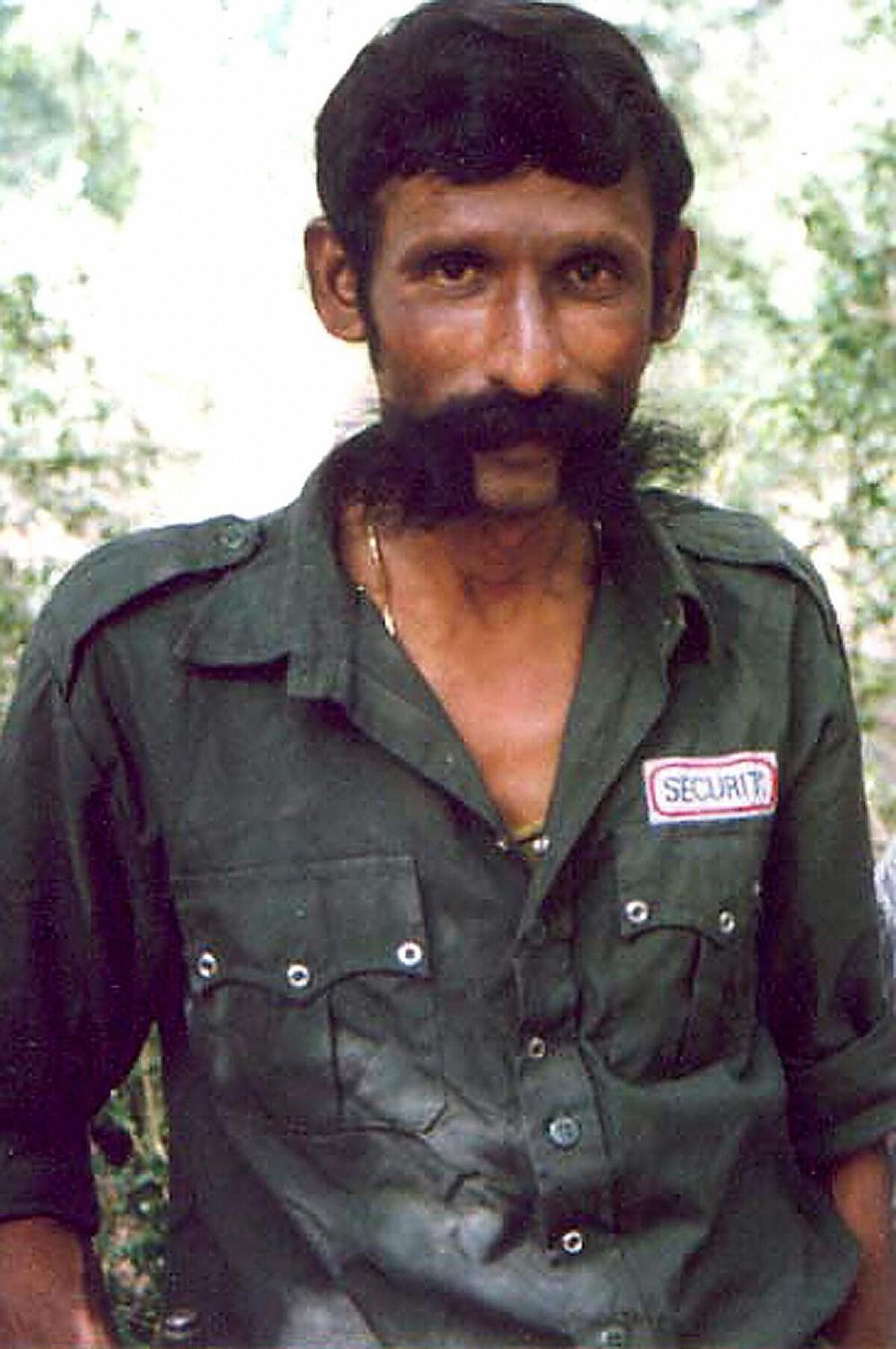

Veerappan, long considered India’s most daring and ruthless bandit, was accused over several decades of kidnapping, smuggling, poaching and carrying out about 100 murders. Known for his huge handlebar mustache, Veerappan reportedly recruited the four then-farmers in southern Karnataka state, initially as informants, then taught them to use firearms and explosives.

In 1993, Veerappan and several gang members, including Meesekar Madaiah, 65, Simon, 45, Gnanaprakasam, 60, and Bilavendran, 60 -- many in southern India use one name -- blew up a security vehicle with land mines, killing 22 police and forestry officials. The four have maintained their innocence since their 2004 conviction for crimes against the state.

Hanging is the preferred execution method in India, a carryover from British days, although few hangmen still practice. Hindalga jail, where the four are held, reportedly recruited staff members to carry out the executions, holding mock hangings recently to hone their skills, according to local media reports. Regulations stipulate that convicts must be executed within 14 days of their rejected clemency appeal by the president, which occurred Feb. 13.

“They are all healthy and well aware that they will be hanged soon,” the prison’s medical officer, Dr. Vasant Yamakanamaradi, told local reporters.

Executions are rare in India, but the pace has picked up recently, with two hangings in three months. In November, the country executed Ajmal Kasab, the sole surviving gunman in the 2008 Mumbai attack that killed 166. And on Feb. 9, Afzal Guru, convicted as an accomplice in a 2001 attack on Parliament, was hung in secret. The last execution before these two was in 2004.

Suhas Chakma, director of New Delhi-based Asian Center for Human Rights, said India should abolish the death penalty because studies show that it doesn’t deter crime. Justice is hardly blind in Indian capital punishment cases, he added. “There is a political element to this,” he said.

Chakma said the execution of Guru, a Kashmiri Muslim, has created ill will among Muslims as the ruling Congress Party approaches 2014 elections. The government failed to notify his family before the hanging.

Accordingly, the Congress Party needs to show it is carrying out non-Muslim executions to appease Muslim voters, Chakma said. “They have to hang some Hindus,” he said.

Government officials have denied any political motivation in their execution policy.

Veerappan, born in 1952, started his colorful criminal career poaching as a teenager. He teamed up with notorious poacher and sandalwood smuggler Xavier Gounder around 1970, trading in banned ivory and killing elephants, police, forestry officials and informers who crossed his path. He eventually edged out Gounder as gang leader.

In the mid-1980s, Veerappan started kidnapping and killing senior government officials, amid reports he axed victims to death and fed their bodies to the fish. The tales spread fear and fueled his infamous reputation.

Along the way, Veerappan developed a reputation for slippery tactics, escaping or eluding capture several times while operating across vast swathes of jungle. Locals feared the gang, said to number around 40 at its peak, but also reaped rewards for assisting gang members.

“His survival instinct is strong,” the Hindustan Times newspaper wrote in 2002. “He has acquired a Robin Hood image which the police find hard to fight.”

In July 2000, Veerappan gained national prominence by kidnapping movie star Rajkumar and holding him for three months, hoping to exchange him for jailed gang members. No exchange occurred, but the gang eventually negotiated a $4.4-million ransom for Rajkumar’s release.

“That escalated the whole problem,” said N. Ram, then-managing director of the Hindu newspaper. “Rajkumar was a superstar.” The actor later said Veerappan moved him between jungle camps over 50 times and was considerate, giving him a shawl as a parting gift.

Police finally caught up with Veerappan in 2004 when an undercover officer, posing as an ambulance driver, offered to take him and three gang members to a clinic, reportedly for an eye problem Veerappan had.

Police surrounded the vehicle and opened fire, hitting all four. Police recovered guns, grenades and several thousand dollars in cash from the ambulance.

On his death, villagers in his native Gopinatham celebrated and exploded fireworks even though many were reportedly related to him, pleased that crippling security around the village would be lifted.

“We are sad, of course,” Veluchamy, a farmer and local friend told the Hindu in 2004. “But we are also happy as we can now restart our normal life.”

ALSO:

Bulgarian prime minister announces resignation

In Syria, more than two dozen dead in latest attack on Aleppo

Tunisian prime minister resigns after failing to reshape Cabinet

mark.magnier@latimes.com

Tanvi Sharma in the New Delhi bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.