Calderon’s war on drug cartels: A legacy of blood and tragedy

MEXICO CITY -- “Excuse me, Mr. President. I cannot say you are welcome here, because for me, you are not. No one is.”

The woman’s voice trembled with bitterness and apprehension. She stood just a few feet away from a low stage where Mexican President Felipe Calderon, his wife, Margarita Zavala, and top members of his Cabinet were seated at a tightly controlled forum in Ciudad Juarez on Feb. 11, 2010.

“No one is doing anything! I want justice, not just for my children, but for all of the children,” she went on. “Juarez is in mourning!”

The woman, later identified as Luz Maria Davila, a maquiladora worker, lost her two sons in a massacre that had left 15 young people dead during a house party in Juarez 12 days earlier.

Calderon initially dismissed the victims as “gang members,” more cogs in the machine of violence that by then was terrorizing every sector of what was once Mexico’s most promising border city. But news reports quickly revealed that the victims of the Villas de Salvarcar massacre were mostly promising students and athletes.

They died only because they were in the wrong place at the wrong time: Juarez hitmen had been ordered to kill everyone at the party because it was believed that rival gang members were in attendance.

“I bet if they killed one of your children, you’d lift every stone and you’d find the killer,” Davila said to the president as the room fell silent after her interruption. “But since I don’t have the resources, I can’t find them.”

Calderon and Zavala remained silent, frowning.

“Put yourself in my shoes and try to feel what I feel,” the mother continued. “I don’t have my sons. They were my only sons.”

It was a searing, unscripted moment in a presidential term that was abundant with them.

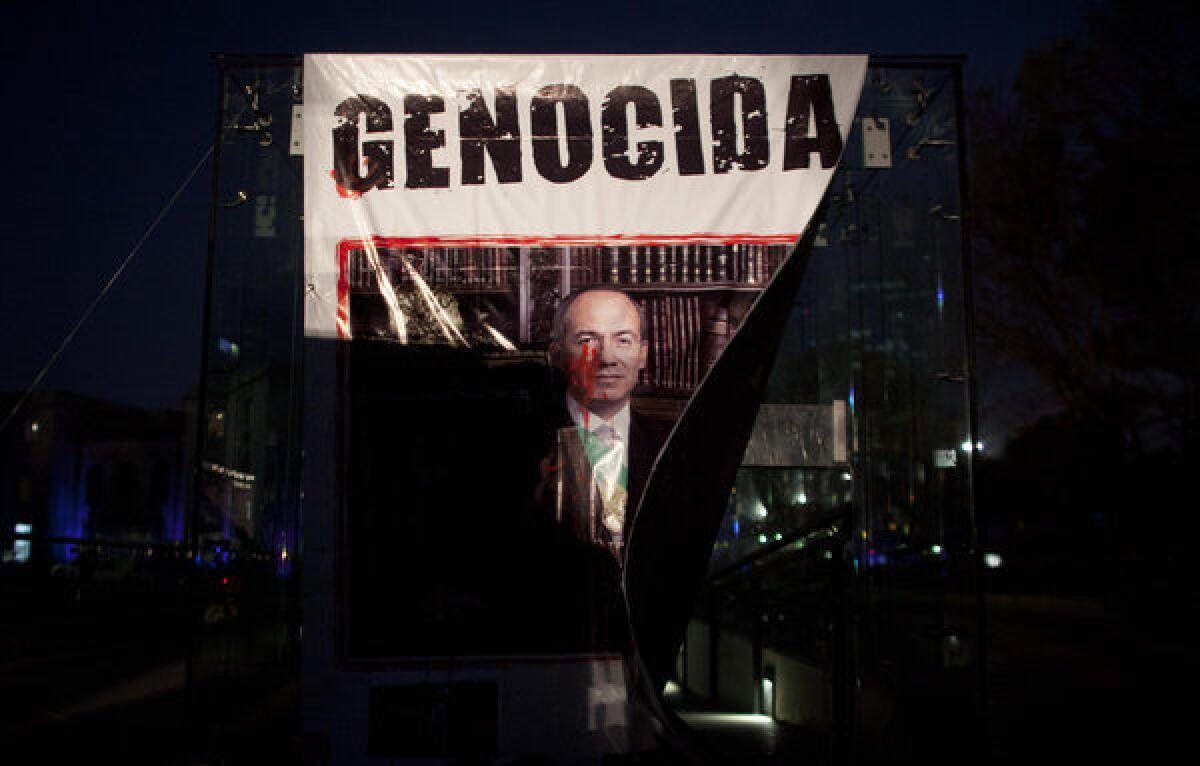

In his six years in office, a term ending Saturday with the swearing-in of his successor, Enrique Peña Nieto, Calderon’s government built bridges and museums, expanded healthcare and led major international meetings on climate change and development. But for the many achievements, the Calderon years will probably be remembered as the bloodiest in Mexico’s history since the Revolutionary War a century ago.

Civilians were mowed down by masked gunmen at parties and funerals. Journalists, mayors, human rights activists, lawyers and police commanders from small towns to big cities were shot while sitting in their cars or going on errands. Regular citizens, from small-business owners to oil workers, were snatched from homes or offices and never heard from again.

While drugs continued to flow north and U.S. government weapons and cash laundered by major global banks flowed south, the Calderon security strategy remained basically unchanged over the years. Its effect was a catastrophic expansion of violence and a crime-solving rate of nearly zero.

For average Mexicans, the extreme violence seen during this sexenio -- as a six-year presidential term is called -- was psychologically and emotionally grueling, particularly for children, experts say. In many parts of Mexico, a culture of fear settled over the population.

Overall, more than 100,000 people were violently killed in Mexico during this term, government figures show. The number of those killed directly tied to the drug war may never be known, as the lines blurred between drug-trafficking violence and violence spurred by the general impunity enjoyed by the drug lords.

The national human rights commission says more than 20,000 people are missing in Mexico. Torture is also believed to be widespread nationally.

During this term, Mexican cartels also expanded their control and firepower to Central America, while clandestine anti-trafficking operations led or funded by the United States grew to unprecedented levels, as The Times reported this week. About half of Mexico’s territory is believed to be under cartel influence.

Here is a rundown of some significant events and markers of Mexico’s drug war from 2006 to 2012 -- the Calderon years.

Military campaign begins

In mid-December 2006, days after assuming the presidency in a chaotic struggle with leftists who refused to recognize his electoral victory, Calderon’s government sent more than 6,700 troops -- soldiers, marines and federal police -- to his home state of Michoacan to launch his fight against organized crime.

On Jan. 3, 2007, Calderon donned a military-green jacket and cap while reviewing progress of the Michoacan campaign in the city of Apatzingan, an image that came to symbolize a looming militarization of Mexico’s struggle against drug gangs.

There was never a formal declaration of war, and the start of the conflict itself is a matter of dispute, as it was with Calderon’s predecessor, Vicente Fox, who first sent soldiers to tackle cartels.

But in mid-2007, Calderon used the term “war” freely in two speeches to describe his government’s efforts. In Guadalajara, he said he was carrying out a “frontal war” against criminals. In Monterrey, he called it a “long-term war.”

As casualties mounted, Calderon’s language about the conflict evolved. In May 2011, he told Mexican migrants in New York that “it’s not a war against narco-traffickers as such.” In recent years, he began urging citizens, foreigners and even journalists to “speak good about Mexico” to outsiders.

Violence in Ciudad Juarez

A sharp increase in homicides registered in January 2008 in Ciudad Juarez signaled the start of the cruelest sub-conflict in Mexico’s drug war, the battle for control of Juarez’s crucial port with the United States, which led to an estimated 10,000 dead.

Businesses were victims of extortion, and owners were brutally gunned down if they refused to pay. Hospitals, even schools, were targets. The violence led to an exodus from the city to El Paso across the Texas border, or to other cities in Mexico. The violence included beheadings, mass executions and bodies hanging from bridges, atrocities that also were seen in Michoacan, Guerrero, Nuevo Leon, Veracruz and elsewhere.

Analysts say the Juarez cartel finally succumbed to the onslaught brought by the Sinaloa federation, with homicide rates dropping this year. However, corruption among federal police and military personnel operating in the area is considered rampant. Human rights abuse claims against authorities ballooned in Ciudad Juarez and the rest of Chihuahua during Calderon’s term.

The Villas de Salvarcar massacre occurred on Jan. 30, 2010, when Luz Maria Davila’s teenage sons, Marcos and Jose Luis, were killed. She still lives in Juarez with her husband and continues to work at a factory on the border.

“In that moment, I felt like no one was listening to me,” Davila said, recalling her confrontation with Calderon in a later interview.

Police director assassinated

In May 2008, Edgar Millan Gomez, the acting director of what was then called the Federal Preventive Police, was shot and killed in his Mexico City apartment by gunmen waiting inside. His slaying was allegedly a retaliation strike by a branch of the Sinaloa cartel.

Michoacan grenade attack

On Sept. 15, 2008, the night before Independence Day, an assailant threw a hand grenade into throngs of people gathered at the main plaza in the Michoacan capital, Morelia, killing seven. The attack was dubbed an act of “narco-terror” and blamed on the local cartel La Familia Michoacana.

Suspicion after crash

On Nov. 4, 2008, as Barack Obama was elected president in the United States, a Learjet carrying Mexico’s second-in-command and a top former prosecutor against organized crime crashed in rush-hour traffic near Chapultepec Park, killing 16 people in total.

The death of Interior Secretary Juan Camilo Mouriño, 37, noticeably shook Calderon, who had called him a close friend. Another passenger was Jose Luis Santiago Vasconcelos, a respected former attorney general who had received death threats.

Government investigators ruled the crash an accident, but popular suspicion remained that the plane was deliberately brought down. Investigative journalists in Mexico explored potential scenarios of an attack linked to organized crime or internal struggles in Mexico’s political right.

Tamaulipas candidate killed

Days before a July 2010 election, the candidate for governor of Tamaulipas and four campaign aides were killed in a highway ambush.

The death of Rodolfo Torre Cantu, candidate for the Institutional Revolutionary Party, was blamed on organized crime and called one of the most high-profile political assassinations in Mexico since the 1994 killing of PRI presidential candidate Luis Donaldo Colosio.

Torre’s brother, Egidio Torre Cantu, replaced him on the ballot and won, as the state became a battleground between the Zetas and Gulf cartels.

Epidemic of fear

As the conflict dragged on, daily life in many parts of Mexico took on an edginess over potential attacks. Mexicans became increasingly afraid to go out at night, and their confidence in authorities dropped year by year.

In May 2010, popping sounds heard at a concert venue near Monterrey led to a stampede that left five people dead.

In May 2011, a video circulated of a Monterrey schoolteacher leading kindergarteners in song as they duck for cover from a shootout nearby. The clip of teacher Martha Rivera Alanis showing bravery and poise in the incident moved television viewers and also led to the greater cries of outrage at the government over the growing reach of violence.

In another dramatic moment caught on tape, in August 2011, a shooting outside a professional soccer match in the city of Torreon was heard in the stands and on the field, causing a panicked scene as fans and players ducked for cover or streamed onto the field to escape. No one was killed or injured.

San Fernando migrants massacred

The transnational aspects of Mexico’s conflict with drug gangs were laid painfully bare in August 2010, when news emerged that a house near San Fernando, Tamaulipas, had been discovered where 72 kidnapped migrants from Central and South America had been executed.

The massacre, blamed on the Zetas, by then also trafficking in humans, was condemned by the global community and met with embarrassment in Mexican society. The sole survivor of the massacre, 18-year-old Luis Freddy Lala Pomavilla, returned to his native Ecuador under heavy guard.

The San Fernando massacre highlighted the dangers migrants face in their attempt to cross Mexico and reach the United States. An estimated 10,000 migrants from Central and South America have gone missing in Mexico, the national human rights commission says.

Death at the Casino Royale

On Aug 25, 2011, gunmen linked to the Zetas stormed into the Casino Royale gambling club in Monterrey and set fire to it. When the smoke cleared, 53 people were dead, an attack that horrified the population.

Calderon, his wife and top administration officials traveled to Monterrey, dressed in black, and stood before a wreath in honor of the victims. It seemed to matter little to the grieving city when arrests were made in the case. The burned-out shell of the Casino Royale remains standing.

Second interior minister killed in aviation crash

On Nov. 11, 2011, Calderon’s government suffered a second loss of its second-in-command when Interior Minister Francisco Blake Mora and seven others were killed in a helicopter crash outside Mexico City.

There was no sign of foul play in the crash. A week earlier, Blake had mentioned the 2008 Learjet crashed that killed Mouriño in a Twitter message. The message turned out to be his last.

Reporters become victims

Dozens of journalists have died during the Calderon term. Although counts differ because the professional ties of the journalists at the times of their death have varied (see this map), Mexico is now considered one of the most dangerous places in the world to report the news.

The string of reporters killed in Veracruz state in the last year came to typify the impunity surrounding the deaths of journalists nationwide. When an arrest was made in the April 2012 death of investigative reporter Regina Martinez, few of her surviving colleagues said they were convinced justice had been served.

Looking ahead

The incoming government of President-elect Enrique Peña Nieto has said it will adjust Calderon’s strategy and focus on reducing the homicide rate. During the presidential campaign, Peña Nieto hired the former director of Colombia’s national police as a security advisor.

A poll released Friday said Mexicans were looking to the transition with measured optimism, with 31% saying Peña Nieto would govern better than Calderon, 22% saying worse, and 22% saying they did not know.

Calderon delivered a final videotaped message to the nation that aired Wednesday night. The video, shot in warm-colored soft filters as Calderon is seen signing a letter at a desk and saluting a flag, ends with him bidding farewell. “Thank you very much, and so long, Mexico!” he says. Calderon begins a research and teaching fellowship at Harvard University in January.

ALSO:

Street protests follow approval of Egypt’s draft constitution

Law enhances Chinese police’s power in disputed South China Sea

Israel announces plans for 3,000 more housing units in West Bank

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.